Summary of Discussions

Perspectives from Australia, Japan, Taiwan, and the United States

Australia, in the face of economic coercion from China in the forms of sanctions and tariffs, has been exploring an array of responses to economic security threats. In the past, Australia attempted to compartmentalize its economic and diplomatic or strategy relations with China, but China’s more active use of economic statecraft and an increasing understanding in the Australian government that economic security issues affect more than just trade or economic engagement has forced Australia to reassess how it can respond effectively to economic coercion. Australian industries have diversified their export markets, building resilience against future economic coercion. By joining the AUKUS partnership and acquiring submarines, Australia also has taken a proactive stance to protect its critical shipping lanes. Likewise, Australia’s participation in regional groupings like the CPTPP trade pact and the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) reinforces its partnerships with likeminded countries and builds protection against economic coercion.

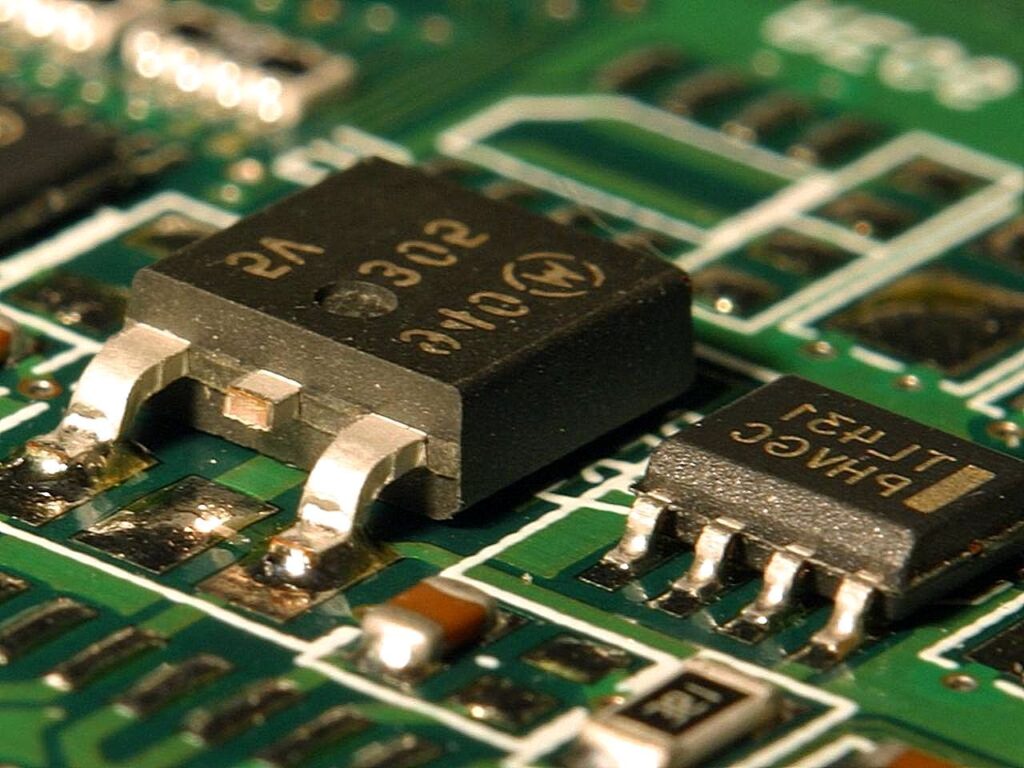

Japan faces several challenges in the economic security debate. These include the implementation of a security clearance system, improving cyber security, and above all securing Japan’s supply chain vis-à-vis China. In the past, Japan had some leverage over China in economic security due to its massive official development assistance. That era has ended, especially after the Chinese export ban of rare earth metals in 2010 following an incident in the contested waters of the East China Sea, after which Japan too realized that China is willing to link economic issues to coerce. Today, Japan is focusing heavily on expanding its economic security tools. However, Japan is concerned with the effectiveness and the goals of the U.S. actions towards China, such as the CHIPS Act. Japanese businesses are willing to comply and take appropriate measures according to U.S. regulations due to their strong memories of the Toshiba-Kongsberg scandal in the 1980s. But because of the complexity and the lack of clarity, these businesses, especially ventures and small and medium-sized enterprises, are concerned with the ongoing development of U.S. regulations on sensitive technologies.

Taiwan, the home of semiconductor giant TSMC, is uniquely situated in the economic security debate. Taiwan’s main concern regarding economic security with China is about protecting its edge in advanced technologies, especially semiconductors, from being either stolen or diverted to China through technology transfers. Chinese economic sanctions against Taiwan have targeted industries that are not salient, such as agriculture and fishery, and have not targeted Taiwan’s key exports. This is largely because China also profits from the triangle of trade between Taiwan, the manufacturing base in China, and the consumer markets in Europe and North America. However, China may be willing to take the risk and sanction Taiwan’s key exports in the future. Taiwan is frequently excluded from multilateral economic arrangements, such as IPEF, CPTPP, and the Wassenaar Arrangement on export controls, and this limits Taiwan’s ability to coordinate with like-minded countries. Unlike the Japanese who experienced the Toshiba incident, Taiwanese businesses have not faced major export control issues in the past. But they are reasonably concerned about the potential effects and the goals of U.S. regulations.

The economic security concerns of the United States are currently focused on technologies critical for military capabilities and maintaining or increasing the U.S. military advantage. After several years of a trade war between the United States and China, the U.S. has taken a strong approach to protect critical technology industries like semiconductors with export controls and support for domestic production in order to make the U.S.’s supply chains more resilient and restrict China’s access to key technology. However, the U.S. still needs to find a balance between unilateral actions and collaboration with allies and likeminded partners. While an economy as large as the U.S. has an outsized influence on the global economy, many of its economic security objectives pertaining to China’s ability to obtain certain technologies will require buy-in and cooperation from allies and partners. Yet the U.S.’s economic security goals and expectations of partners may not be clear, and key partners in some areas may not be comfortable with choosing between the United States and China.

Issues and Challenges

The participants discussed several economic security issues of mutual concern. One of the main challenges is how to build an effective array of economic security tools, both offensive and defensive. This is the heart of the issue with responding to economic coercion, as retaliatory or punitive measures can be controversial. A participant offered a Cold War example of the United States using various economic pressures on the Soviet Union, contrasting with Australia’s reluctance in recent years to use obvious retaliatory measures like restricting China’s access to Australian iron ore, one of China’s vulnerable points. Yet, despite the sensitivity of employing economic leverage, not using this kind of measure leaves obvious tools unused.

Central to the concept of an economic security toolkit is the recognition that different governments have different tools available to them. For example, Japan’s ability to impose export controls under its Foreign Exchange and Trade Act varies depending on whether Japan is acting in concert with a formal international agreement or is unilaterally imposing sanctions; Japan has most recently faced this issue in responding to various points in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

A participant observed that national security is sometimes viewed as equivalent to or a degree of self-sufficiency. The realizations during the pandemic that global supply chains are deeply complex, and no part of the world is totally insulated from global shocks, as well as the growing awareness of an overdependence on China’s supply and markets, have prompted reflections on the meaning of resilience. Further, some governments have taken steps to strengthen specific domestic industries through onshoring, such as the U.S.’s CHIPS Act for semiconductor production. But the impulse to expand self-sufficiency may be a questionable approach, especially considering the difficulty or impossibility of replicating global supply chains domestically. More importantly perhaps is that the strength of likeminded partners also matters for national and economic security, so friend-shoring, ally-shoring, or similar efforts to build supply chains among partners are an approach to consider. If partners can move beyond the idea of national resilience meaning self-sufficiency, they might also have expanded options for burden-sharing, by integrating key supplies such as fuel or munitions.

The participants identified a challenge that while economic groupings are increasingly important in economic security discussions, Taiwan is excluded from many of these arrangements, including the CPTPP and the IPEF. Because of the importance of economic partners being able to fully rely on each other to strengthen their collective and individual economic security, institutionalization and trust go hand in hand with friend-shoring. In addition, multilateral organizations that provide mutual assistance and support in economic security may help to deter economic coercion, such as an “economic NATO” framework that has been suggested by experts. Taiwan’s exclusion from the existing multinational trade arrangements may limit Taiwan’s ability to partner with other like-minded economies in the area of economic security.

A different impulse in the economic security debate is the matter of resilience, which is often linked to diversification, such as adjusting supply chains or trading partners to prevent overreliance on a narrow set of sources. However, resilience is more complicated than diversification. An example raised by a participant is the political intervention of governments in corporate decisions, such as asking specific companies to not export to certain countries, as the United States has done with export controls on semiconductor-related industries. Though export controls on industries with key technologies may sometimes be necessary, the question of how far is too far is one that the United States and its partners need to figure out. The balances between keeping some markets competitive while allowing government intervention in other markets, and between making allies and partners less vulnerable while undermining competitors, require nuanced economic security policies. Further, it is necessary to remember that the U.S. and China are working with different economic mechanisms, with China more able to use economic statecraft domestically and internationally to achieve its goals.

Participants discussed reactions towards the recent U.S. export control measures, including the October 2022 regulations on semiconductor-related companies and human resources. While the U.S.’s partners share concerns with China’s access to semiconductors, including technology theft or forced transfers and brain-drain of workers in the industry, the export controls are sending several signals. There is concern that the U.S. may favor its domestic semiconductor producers in the export approval process, or that smaller companies within the semiconductor supply chains may not have the legal resources to successfully navigate the complexities of U.S. export regulations. The differing perspectives of government and private sector actors will also play a role in whether the U.S.’s partners align and to what degree. Moreover, given the importance of Taiwan’s “silicon shield,” which may make China wary of damaging Taiwan’s facilities in a military maneuver, the impact of U.S. export controls on Taiwan’s production and China’s ability to import the machinery it needs to produce high-end semiconductors will be important to watch.

For U.S. partners, the biggest question is what outcome the U.S. seeks from these policies, whether preventing the transfer of certain technology, restricting China’s production capabilities, preventing China from improving its industrial infrastructure and capabilities, or even preventing China from accessing advanced semiconductors. The policy intent, and any expectations of solidarity from partners, need to be clearly defined for partner governments and industries. This is especially important given how difficult it can be for businesses to clearly distinguish which technologies are sanctioned and which are not. While export controls are effective to a certain extent, many countries and companies have large interests in the Chinese market and may consider separate supply chains as a path forward.

China’s reaction to the U.S. export control measures will likely be to invest heavily in its domestic semiconductor industry. Participants offered different perspectives on how quickly China might be able to strengthen its domestic production, though given the complexity of the process, China may need a long time to catch up to the West, which also provides Taiwan, the U.S., and others time to invest in themselves and collaborate. In the meantime, however, China will likely focus its investments in more mature, low-end semiconductor markets, which poses the risk of these markets coming under increased control or involvement of the Chinese government. But China may face challenges on the demand side of the equation as well as the supply, if the U.S. and others decide to prohibit the import of products containing Chinese semiconductors. For example, Apple announced in October that it would not use Chinese chips in its new cell phone; if other companies follow suit, China’s semiconductor industry could find itself without sufficient markets, making it difficult for China to advance.

Though semiconductors are the focus of U.S.-China economic competition at present, the participants noted that other key technologies may see further U.S. sanctions, such as artificial intelligence or biotechnologies. For semiconductors and other technologies, a similar set of challenges faces each of the four governments: how to prevent the leakage of knowledge and technical expertise in these industries. In this area of economic security, protecting key technologies, even with the cooperation of partners, will remain the most difficult task.

Dialogue Participants

Ping-kuei Chen, Associate Professor, Department of Diplomacy, National Chengchi University

Zack Cooper, Senior Fellow, American Enterprise Institute

Christopher Johnstone, Senior Advisor and Japan Chair, Center for Strategic and International Studies

James Schoff, Senior Director, U.S.-Japan NEXT Alliance Initiative, Sasakawa Peace Foundation USA

Kazuto Suzuki, Professor, Graduate School of Public Policy, University of Tokyo

Ayumi Teraoka, America in the World Consortium Post-Doctoral Fellow, University of Texas at Austin

Mark Watson, Director, Australian Strategic Policy Institute Office in Washington, DC

Thomas Wilkins, Senior Fellow, Australian Strategic Policy Institute

Chien-huei Wu, Research Professor, Institute of European and American Studies, Academic Sinica

Moderator: Yuki Tatsumi, Senior Fellow and Co-Director, East Asia Program, Stimson

With remarks by Richard Cronin, Distinguished Fellow, Stimson