Introduction

Human rights defenders are people who, individually and in association with others, act to promote, protect, or strive for the protection and realization of human rights and fundamental freedoms through peaceful means.1UN General Assembly, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, Situation of human rights defenders, A/73/215 (23 July 2018), 5-6; See also, UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, “Human Rights Defenders: Protecting the Right to Defend Human Rights,” Factsheet No. 29, 2004, 2, 7-10, https://www.ohchr.org/en/publicationsresources/pages/factsheets.aspx. They gather data on issues that would otherwise be ignored, provide analyses of government policies and legislation, and propose solutions to address policy and implementation gaps. Defenders support and empower victims to access justice, and foster dialogue and mediate between governments or businesses and affected communities. These advocates expose and work to end human rights violations, and to promote good governance, transparency, and the rule of law. As a result of this work and many more activities they undertake, human rights defenders are recognized as essential actors in the fulfilment of human rights and the achievement of the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.2UN General Assembly Resolution 53/144, Declaration on the Right and Responsibility of Individuals, Groups and Organs of Society to Promote and Protect Universally Recognized Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, A/RES/53/144 (9 December 1998); UN Human Rights Council Resolution 31/32, Protecting human rights defenders, whether individuals, groups or organs of society, addressing economic, social and cultural rights, A/HRC/RES/31/32 (24 March 2016), para. 7; and UN Human Rights Council Resolution 40/11, Recognizing the contribution of environmental human rights defenders to the enjoyment of human rights, environmental protection and sustainable development, A/HRC/RES/40/11 (21 March 2019), para. 2; UN General Assembly Resolution 74/146, Implementing the Declaration on the Right and Responsibility of Individuals, Groups and Organs of Society to Promote and Protect Universally Recognized Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms through providing a safe and enabling environment for human rights defenders and ensuring their protection, A/RES/74/176 (18 December 2019), para. 2; and UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, Implementing the Declaration on the Right and Responsibility of Individuals, Groups and Organs of Society to Promote and Protect Universally Recognized Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms through providing a safe and enabling environment for human rights defenders and ensuring their protection, including in the context of and recovery from the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, A/RES/76/174 (16 December 2021), para. 1.

“Human rights defenders do not heroically stand in front of or apart from the rest of us; they are each of us and among us, they are ourselves, our parents, our siblings, our neighbours, our friends and colleagues, and our children.”3UN General Assembly, Situation of human rights defenders, 4.

– UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders Michel Forst

Despite the vital role of human rights defenders in the achievement of these goals, from 2015 to 2019, the United Nations (UN) recorded at least 1,940 killings and 106 enforced disappearances of human rights defenders,4The UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders noted that 1,323 human rights defenders were reported killed between 2015 and 2019. (UN Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, Final warning: Death threats and killings of human rights defenders, A/HRC/46/35 (24 December 2020), 5). journalists, and trade unionists across 81 countries, with more than half the killings occurring in Latin America and the Caribbean.5UN Secretary General, The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2020 (New York: United Nations, 2020), 57, https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2020/. Those seeking to promote human rights confront great challenges in their work, particularly in a context where 117 of 197 countries are reported to have “serious civic space restrictions.”6UN Secretary General, The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2020 (New York: United Nations, 2020), 57, https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2020/. In addition to threats to their lives, human rights defenders regularly face detention, enforced disappearance, surveillance, criminalization, and other grave risks as a result of, and with the aim of hindering, their work.7Civicus, “People Power Under Attack 2021,” Marianna Belalba Barreto, Josef Benedict, Débora Leão, Sylvia Mbataru, Aarti Narsee, Ine Van Severen and Julieta Zurbrigg, (2022), 5-6, https://findings2021.monitor.civicus.org/. Some defenders are at heightened risk; for example, Front Line Defenders found that 69 percent of the advocates they recorded as killed in 2020 worked on land, Indigenous peoples’, and environmental rights, and 28 percent worked on women’s rights.8Front Line Defenders, “Front Line Defenders Global Analysis 2020,” (12 February 2021), 4, https://www.frontlinedefenders.org/en/resource-publication/global-analysis-2020.

Recognizing these obstacles and the important role that human rights defenders play, the UN General Assembly adopted the Declaration on Human Rights Defenders in 1998.9UN General Assembly Resolution 53/144, A/RES/53/144. Although the term “human rights defender” is not used in the Declaration, its definition is drawn from the activities described in that document. The instrument sets out the rights of every person to undertake such activities,10Ibid., art. 1. and the state responsibilities to protect those rights.11Ibid., art. 2.

There have been consistent state efforts, including at the General Assembly, the UN Human Rights Council, and the UN Security Council, to build upon the Declaration and strengthen the framework for a safe and enabling environment for the defense of human rights. However, human rights defenders in many countries continue to face grave and complex challenges, including threats to their lives, as a result of their peaceful activities. This brief examines possibilities for further state action at the UN to increase the safety and security of human rights defenders. It outlines major trends, gives an overview of UN efforts, and sets out key instruments and state commitments in relation to human rights defenders. It then explores key risks and opportunities for strengthening UN action, offering recommendations for member states to advance this agenda and better ensure that human rights defenders everywhere are able to freely and safely undertake their vital work.

Trends in the Situation of Human Rights Defenders

In 2021, Civicus stated that 88.5 percent of the world’s population lived in countries the organization rated as “closed, repressed, or obstructed.”12Civicus, “People Power Under Attack 2021”, 5. Those seeking to promote human rights in these contexts consequently face great obstacles in their work. The UN reported that 331 people seeking to promote human rights were killed across 32 countries in 2020 alone.13UN Secretary General, The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2021, 59. The UN Special Rapporteur on human rights defenders emphasizes that underreporting is common,14UN Human Rights Council, A/HRC/46/35, 5. so the numbers of killings are likely to be much higher.

Similar to previous years, Front Line Defenders reported that in 2020 the most common other violations against human rights defenders were detentions or arrests, legal action, other harassment, raids or break-ins, smear campaigns, and torture or ill-treatment.15Front Line Defenders, “Front Line Defenders Global Analysis 2020,” p. 5. These findings are in line with the research of other organizations monitoring civic space and the situation of human rights defenders; see, for example, Civicus, “People Power Under Attack 2021,” 5-6. Surveillance and threats were not cited, as “the vast majority of HRDs experience these violations on an ongoing basis.”16Front Line Defenders, “Front Line Defenders Global Analysis 2020,” p. 5. In addition, the law is frequently used as a weapon against human rights defenders, with advocates facing trumped-up charges ranging from terrorism to tax evasion, from spreading fake news to trespass.17Ibid. Finally, many human rights defenders face digital risks, such as online threats, social media account hacking, and phone surveillance.18Ibid. The nature of targeting of human rights defenders varies between geographic regions, and threats and harassment are directed at defeders themselves, their families, their colleagues, or their communities.

In reports and communications with states, the mandate of the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders has joined civil society observers in identifying groups that – often due to intersecting elements of identity, such as gender, ethnicity, faith, and sexual orientation – are frequently at increased risk when they engage in peaceful activities to promote human rights. Such individuals often come from marginalized communities and can also face specific kinds of threats or impacts. These groups include human rights defenders who are women,19UN Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, Situation of women human rights defenders, A/HRC/40/60 (10 January 2019); and UN Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, Women human rights defenders and those working on women’s rights or gender issues, A/HRC/16/44 (20 December 2010). Indigenous 20See multiple reports of the UN Special Rapporteur, Situation of human rights defenders, in particular: A/72/170 (19 July 2017), A/71/281 (3 August 2016), A/68/262 (27 March 2013), and A/HRC/19/55 (21 December 2011), https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/SRHRDefenders/Pages/AnnualReports.aspx. and lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans (LGBT);21UN Human Rights Council, Situation of women human rights defenders, A/HRC/40/60; UN Human Rights Council, Women human rights defenders and those working on women’s rights or gender issues, A/HRC/16/44. defenders of the rights of people on the move;22This term is a broader framing than the defenders of migrant rights. (UN Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, Human rights defenders on the rights of people on the move, A/HRC/37/51 (16 January 2018).) those defending land and environmental rights and working on issues of human rights and business;23“One in two victims of killings recorded in 2019 by OHCHR had been working with communities around issues of land, environment, impacts of business activities, poverty and rights of Indigenous peoples, afrodescendants and other minorities.” (UN Human Rights Council, A/HRC/46/35, p.5.) See other reports of the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, in particular A/72/170, A/71/281, A/68/262, and A/HRC/19/55, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/SRHRDefenders/Pages/AnnualReports.aspx. defenders working to combat corruption;24Report by the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, forthcoming, information at https://www.transparency.org/en/blog/un-special-rapporteur-human-rights-defenders-anti-corruption-activists and https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/SRHRDefenders/Pages/anti-corruption.aspx. as well as human rights defenders operating in conflict and post-conflict situations.25UN Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, Human rights defenders operating in conflict and post-conflict situations, A/HRC/43/51 (30 December 2019).

Human rights violations against human rights defenders can be committed by state actors, such as government representatives, law enforcement officials, or the military. Non-state actors (e.g., criminal groups or businesses) can also target defenders, with states unable or unwilling to take action to prevent these incidents or practices.

Attacks, including killings of human rights defenders, often come in a context of structural violence and inequality, including in societies in conflict, and as the product of patriarchal, heteronormative systems. Threats and killings often happen when a context of negativity has been created around defenders generally, or around particular defenders. This can make them vulnerable to attacks.26UN Human Rights Council, A/HRC/46/35, 5.

– UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders Mary Lawlor

The UN has underlined that acts of violence and discrimination are fueled by widespread impunity. With those responsible not being held to account, killings are more likely to continue.27Ibid.; UN Secretary General, The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2021, 59. Weak institutions, corruption, lack of an independent judiciary, the absence of a differentiated approach to access to justice, and structural barriers such as the lack of access to public information, are some of the drivers of impunity.28UN General Assembly, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, Impunity for human rights violations committed against human rights defenders, A/74/159 (15 July 2019), 10. Fragile states in democratic transition that have ongoing armed conflicts or that are under occupation face additional challenges.29Ibid. The Special Rapporteur has found that to ensure access to justice, states must, inter alia, recognize the important role of defenders, conduct full and effective investigations, and hold those responsible to account.30Ibid., 10-15. In this 2019 report, the Special Rapporteur examines many other barriers to access to justice for human rights defenders.

The Special Rapporteur has highlighted that political will is essential to the protection of human rights defenders. States need this will to proactively build safe environments (including by removing legal and administrative barriers and practices that hinder defenders’ work) and to combat impunity. Without political will, the Special Rapporteur has noted, “any other action will be insufficient and possibly ineffective.”31Ibid., 22.

Member State and UN Efforts to Protect Human Rights Defenders

Member States

After nearly two decades of negotiations,32UN General Assembly, Situation of human rights defenders, 5. the Declaration on Human Rights Defenders33UN General Assembly Resolution 53/144, A/RES/53/144. was adopted by consensus at the General Assembly in 1998. The Declaration commits UN member states to safeguard the right of everyone to promote, protect, or strive for the protection and realization of human rights and fundamental freedoms through peaceful means. The instrument also recognizes the key role of human rights defenders in the realization of the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and international human rights law treaties. The UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders has identified the Declaration as a paradigm shift “in the understanding of the human rights project: from a task accomplished mainly through the international community and States to one that belongs to every person and group within society.”34UN General Assembly, Situation of human rights defenders, 3. Although many states supported the idea of the Declaration, it also faced strong opposition.

Negotiations on the Declaration on Human Rights Defenders and Beyond

Negotiations were very challenging during the lead-up to and following the presentation of the first draft of the Declaration by Canada and Norway in 1987. A key concern of those opposed to the text (in particular, Cuba, China, Syria, Mexico, and members of the ‘Eastern Bloc’) was state sovereignty. Some states argued that the instrument should not protect individuals who resisted the state (except in the context of colonialism or apartheid). They also held the position that human rights issues should only be dealt with between states at the international level, and by the state – not individuals – at the national level.35Janika Spannagel, “Declaration on Human Rights Defenders (1998),” https://www.geschichte-menschenrechte.de/en/hauptnavigation/schluesseltexte/declaration-on-human-rights-defenders-1998. Ultimately, the Declaration – described by civil society deeply involved in the process as the “absolute minimum” – was adopted by consensus, with 55 co-sponsors from all regions.36Ibid. However, shortly before adoption, Egypt led 26 countries (all in Asia and Africa, apart from Cuba) in submitting their own “declaration.”37UN General Assembly, “Letter Dated 18 November 1998 from the Permanent Representative of Egypt to the United Nations Addressed to the President of the General Assembly,” A/53/679 (18 November 1998). This document set out how these states considered that the Declaration on Human Rights Defenders should be interpreted, emphasized the primacy of national law over international principles, and noted the need to take into account the cultural, religious, economic, and social background of societies.38Petter Wille and Janika Spannagel, “The History of the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders: Its Genesis, Drafting and Adoption,” Universal Rights Group, March 11, 2019, https://www.universal-rights.org/blog/the-un-declaration-on-human-rights-defenders-its-history-and-drafting-process/.

Such tensions have remained at the core of state efforts at the UN to strengthen protections for human rights defenders. States opposing resolutions on human rights defenders at the Third Committee and the Human Rights Council make arguments related to:

- State sovereignty (in terms of states emphasizing national security and the prevention of resistance against the state, as well as the wish to affirm the primacy of national over international law);

- The need for defenders to act in accordance with a country’s morals and customs;

- The importance of avoiding the creation of new rights (in the context, for example, of calling for the removal of references to specific groups of defenders); and

- The very use and definition of the term “human rights defender.”

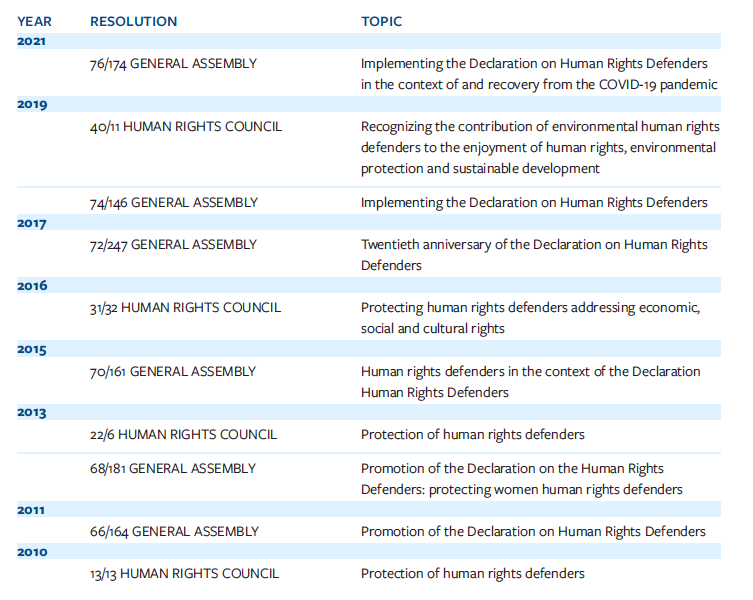

Reaffirming the contents of the Declaration, the member states have adopted six resolutions focused solely on human rights defenders at the General Assembly and four at the Human Rights Council since 2010.39The year 2010 is selected as it is the first year that the UN Human Rights Council adopted a resolution focused specifically on human rights defenders. The UN Commission on Human Rights (which the UN Human Rights Council replaced in 2006) also adopted resolutions on human rights defenders, including every year from 2000-2005. In addition, many resolutions refer to human rights defenders and civic space. In addition, many other resolutions make reference to defenders and civic space.40See, for example, Human Rights Council resolutions on civil society space (the most recent, A/HRC/RES/47/3, was adopted in 2021); cooperation with the UN, its representatives, and mechanisms in the field of human rights (the most recent, A/HRC/RES48/17, was adopted in 2021); and on country situations (e.g., Belarus, resolution A/HRC/RES/45/1, adopted in 2020); and General Assembly resolutions on the rights of Indigenous peoples (the most recent, A/76/459, was adopted in 2021). The defender-specific resolutions are examined in more detail in the next section, and all but two of the 10 passed by consensus. 41The two non-consensus resolutions were UN General Assembly Resolution 70/161, Human rights defenders in the context of the Declaration on the Right and Responsibility of Individuals, Groups and Organs of Society to Promote and Protect Universally Recognised Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, A/RES/70/161 (17 December 2015), and UN Human Rights Council, A/HRC/RES/31/32. In recent years, the Security Council has also given attention to the roles played and risks faced by women human rights defenders in the context of the women, peace, and security agenda.42In an Arria-formula meeting, “Reprisals against Women Human Rights Defenders and Women Peacebuilders” in February 2020, and in an open debate, “Protecting Participation: Addressing Violence Targeting Women in Peace and Security Processes,” in January 2022.

UN Resolutions on Human Rights Defenders

These resolutions are led by Norway, with the support of a core group of supportive states and civil society. They have been brought every two years at the Third Committee and every three years at the March session of the Human Rights Council. In terms of the negotiation process for each resolution, Norway identifies potential topics to be addressed and confirms which of these have the support of allied states. Norway also meets with civil society organizations who propose topics and express their goals for the resolution and what the text would incorporate. Norway then drafts the text and leads negotiations, including engagement with opposition states, consistently aiming to achieve a consensus document. The draft resolutions have been tabled with a varying number of co-sponsors (the most recent resolution had 85 co-sponsors at the General Assembly,43Albania, Andorra, Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina, Armenia, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bolivia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Botswana, Brazil, Bulgaria, Cabo Verde, Canada, Central African Republic, Chile, Colombia, Congo, Costa Rica, Côte d’Ivoire, Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Denmark, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Estonia, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Guatemala, Honduras, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Lebanon, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Mali, Malta, the Marshall Islands, Mexico, Micronesia , Monaco, Mongolia, Montenegro, Myanmar, the Netherlands, New Zealand, North Macedonia, Norway, Palau, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Republic of Korea, the Republic of Moldova, Romania, San Marino, São Tomé and Príncipe, Serbia, Sierra Leone, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Timor-Leste, Tunisia, Ukraine, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the United States of America, Uruguay, and Vanuatu. and 72 at the Human Rights Council.44Albania, Andorra, Angola, Argentina, Armenia, Australia, Austria, the Bahamas, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Botswana, Brazil, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Canada, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Denmark, El Salvador, Estonia, Fiji, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Ghana, Greece, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Hungary, Iceland, Indonesia, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malawi, Maldives, Malta, the Marshall Islands, Mexico, Mongolia, Montenegro, Mozambique, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Poland, Portugal, the Republic of Korea, the Republic of Moldova, Romania, Senegal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Timor-Leste, Tunisia, Ukraine, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Uruguay, and the State of Palestine.)

United Nations

The UN Secretary-General, through his Call to Action for Human Rights45UN, The Highest Aspiration: A Call to Action for Human Rights (2020), https://www.un.org/en/content/action-for-human-rights/index.shtml. and publication of the UN Guidance Note on the Protection and Promotion of Civic Space,46UN, Protection and Promotion of Civic Space (September 2020), https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/CivicSpace/Pages/UNRoleCivicSpace.aspx. has affirmed that the UN system should empower civil society, enhance civic space, and assist states to create safe and enabling environments for human rights defenders.47See ibid., 5-14. The instruments also emphasize the importance of civic space in the successful implementation of the three pillars of the UN.

The UN has focused specific attention on reprisals and intimidation against human rights defenders cooperating or seeking to cooperate with its mechanisms. Between 2010 and 2020, the Secretary-General documented a total of 709 such cases or situations.48International Service for Human Rights, UN Action on Reprisals: Towards Greater Impact (May 7, 2021), 2, https://ishr.ch/defenders-toolbox/resources/reprisals-ishr-launches-analysis-of-709-reprisals-cases-documented-by-the-un-secretary-general/. UN bodies address49Different UN mechanisms have processes in place to address reprisals. For more information, see UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, “The role of key UN human rights mechanisms in addressing reprisals,” https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Reprisals/Pages/RoleOfKeyUNHRMechanisms.aspx. and draw attention to this issue regularly50,See annual reports of the UN Secretary-General on cooperation with the UN, its representatives, and mechanisms in the field of human rights communications. See also information at https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Reprisals/Pages/RoleOfKeyUNHRMechanisms.aspx. including through General Assembly and Human Rights Council resolutions, 51There are five UN Human Rights Council resolutions dedicated to the topic (A/HRC/RES/48/17, A/HRC/RES/42/28, A/HRC/RES/36/21, A/HRC/RES/24/24, and A/HRC/RES/12/2), and UN General Assembly human rights defender-specific resolutions also address it (A/RES/74/146 and A/RES/72/247), all available at https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Reprisals/Pages/Resolutions.aspx.and an open debate and an Arria-formula meeting of the Security Council. 52The open debate, “Protecting Participation: Addressing Violence Targeting Women in Peace and Security Processes,” took place in January 2022, and the Arria-formula meeting, “Reprisals against Women Human Rights Defenders and Women Peacebuilders,” occurred in February 2020. Since 2012, the Secretary-General has reported annually to the Human Rights Council, and in 2016, the Secretary-General designated the Assistant Secretary-General for Human Rights to lead the efforts within the UN system to address the increase in reprisals. The Assistant Secretary-General engages the UN, member states, and other stakeholders, and advises the Secretary-General and the High Commissioner on Human Rights on how to strengthen UN-wide action for prevention of, protection against, investigation into, and accountability for reprisals.

The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, currently Michelle Bachelet, and her Office (OHCHR) support the efforts of UN member states and the UN system related to human rights defender protection. The High Commissioner regularly refers to potential, past, or ongoing human rights violations against human rights defenders in her statements, reports, and engagement with individual states.53UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Protecting and expanding civic space, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/CivicSpace/Pages/ProtectingCivicSpace.aspx. The OHCHR seeks to: support opportunities to improve national civic space, while enhancing strategic responses to threats; strengthen good protection practices; raise the visibility and increase support for the work of defenders and influence the narrative regarding defenders and their work; monitor trends in civic space and the situation of human rights defenders; and mainstream civic space issues in the UN.54Ibid. In addition, the OHCHR is responsible for data collection and reporting on Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Indicator 16.10.1 on the number of human rights defenders killed, kidnapped, or subjected to enforced disappearances, arbitrary detention, or torture.

SDG 16 and Human Rights Defenders

The situation of human rights defenders is a key element in assessing state achievement of SDG 16 on peace, justice, and strong institutions. Indicator 16.10.1 specifies the number of verified cases of killing, kidnapping, enforced disappearance, arbitrary detention, and torture of journalists, associated media personnel, trade unionists, and human rights advocates in the previous 12 months. While not providing a full picture of the context in which human rights defenders conduct their work, it provides an important snapshot. However, the ALLIED coalition (a civil society grouping) found that between 2015 and 2019, only 14 countries had reported any cases of violence against human rights defenders to the UN.55Central African Republic, Chile, Colombia, Fiji, Iceland, Kenya, Mauritius, Mexico, Mongolia, Nigeria, Palau, Philippines, State of Palestine, Uruguay (see Alliance for Land Indigenous and Environmental Defenders (ALLIED coalition), A Crucial Gap: The Limits to Official Data on Attacks against Defenders and Why It’s Concerning (2020), 8, https://accessinitiative.org/blog/why-arent-countries-reporting-environmental-defender-killings). Only three of the 162 countries that submitted Voluntary National Reviews during the period had indicated that at least one human rights defender had been killed or attacked,56Central African Republic, Nigeria, and Palestine (see The Access Initiative, “Why Aren’t Countries Reporting Environmental Defender Killings?,” January 25, 2022, https://accessinitiative.org/blog/why-arent-countries-reporting-environmental-defender-killings). Data from ALLIED coalition, A Crucial Gap: The Limits to Official Data on Attacks against Defenders and Why It’s Concerning, 8. and 94 percent of countries did not report on this topic at all.57Data from ALLIED coalition, 8.

Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders

The mandate of a UN expert focused on the issue of human rights defenders, now known as the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, was created by member states in 2000.58In 2000, the UN Commission on Human Rights requested the creation of a Special Representative of the Secretary-General of the United Nations on human rights defenders. In 2008, the UN Human Rights Council, which replaced the Commission, retained the mechanism as a special procedure of the Council: the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders. The position is currently held by Mary Lawlor. The independent expert uses its very limited resources59The Special Rapporteur is supported by one staff member of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Every month, it receives hundreds of allegations of violations against human rights defenders, and can only investigate and take action on a small proportion of these. to provide technical assistance to states (as well as to civil society, national human rights institutions, businesses, and other relevant actors) regarding the recognition and protection of human rights defenders. The Special Rapporteur also holds these actors accountable to their commitments and obligations under international human rights law.

The expert sends communications to states regarding allegations of human rights violations against defenders, as well as problematic laws and policies, and issues press releases on such situations. The Special Rapporteur also visits states,60The Special Rapporteur can only conduct a visit if it is invited to do so by the state in question. While some states approach the Special Rapporteur directly to invite a country visit, the Special Rapporteur may also request such invitations. Whether a state issues an invitation (independently or in response to a request) is an indicator of its commitment to human rights defender protection. following government invitations, to report on situations in countries and to make recommendations for improvements.

Mandate holders have highlighted global trends and challenges to the protection of human rights defenders, and drafted reports exploring long-standing and emerging issues of concern or groups of defenders most at risk. These topics include impunity for violations against human rights defenders; long-term detention, death threats, and killings of defenders; smear campaigns; and defenders working on business and human rights, land, and environmental issues.61As understanding and experience in some areas have evolved, the Special Rapporteur has revisited some topics, for example major obstacles to defender protection like impunity, as well as the threats and protection needs of women human rights defenders and defenders working on rights related to gender and sexuality. The mandate has repeatedly examined the situation of defenders engaged in issues related to business and human rights, the environment, land, and Indigenous rights.

State Commitments to Protect Human Rights Defenders

This section looks more closely at state commitments to protect human rights defenders. It examines where and how state commitments have been made, gives an overview of what the state commitments are, and provides brief information and two examples of how UN resolutions have applied these commitments to specific groups of human rights defenders and to particular situations.

Key Instruments

State commitments to protect human rights defenders and create a safe and enabling environment for the promotion and protection of human rights are set out in several instruments. The primary document is the Declaration on Human Rights Defenders.62UN General Assembly Resolution 53/144, A/RES/53/144. The Declaration applies the existing state obligations under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights63UN General Assembly Resolution 217 A III, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, A/RES/3/217 A (10 December 1948). and the international human rights treaties64In particular, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/cescr.aspx; and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/ccpr.aspx, and its first Optional Protocol, https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/opccpr1.aspx. to the issue of human rights defenders, identifying state duties in relation to the rights and responsibilities of defenders to promote and protect human rights. Adopted by consensus, it demonstrates the clear commitment of states to this topic.

Since 2010, the General Assembly and the Human Rights Council have passed 10 resolutions focused solely on the issue of human rights defenders, further exploring the responsibilities of states and other stakeholders in these areas. Many other resolutions have reinforced these instruments and further elaborated upon state duties and commitments, including in specific country situations. These resolutions incorporate language on human rights defenders, emphasize the importance of protecting and promoting civic space and fundamental freedoms, and underline the need to prevent and respond to reprisals against human rights defenders cooperating or seeking to cooperate with the UN.65See, for example, Human Rights Council resolutions on civil society space; cooperation with the UN, its representatives, and mechanisms in the field of human rights and on country situations; and General Assembly resolutions on the rights of Indigenous peoples, as cited in note 38.

States have also indicated their commitment to the issue by maintaining an independent expert focused on the issue of human rights defenders, the Special Rapporteur, for 20 years.66Most recently by consensus in 2020 (UN Human Rights Council Resolution 43/16, A/HRC/RES/43/16 (22 June 2020)). The Special Rapporteur has fleshed out the responsibilities of different actors, advanced understanding of international standards, and offered recommendations for action by states and others to create a safer and more enabling environment for human rights defenders. Many UN special procedures, such as the Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association,67See, for example, UN General Assembly, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association, Celebrating women in activism and civil society: the enjoyment of the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association by women and girls, A/75/184 (20 July 2020). have also made detailed recommendations in these areas. Others have examined the situation of human rights defenders covered by their mandates, for example the Special Rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples.68See, for example, UN General Assembly, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples, Attacks and criminalization of Indigenous human rights defenders, A/HRC/39/17 (10 August 2018).

In relation to states’ duties under the conventions they have ratified, UN Treaty Bodies have regularly explored human rights defender issues in their jurisprudence, outlining state obligations and making recommendations to governments.69See, for example, “Joint Statement by a group of Chairs, Vice-Chairs and members of the UN human rights Treaty Bodies and the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders,” https://www.ohchr.org/en/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=23154&LangID=E; UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, “Human rights defenders and economic, social and cultural rights,” E/C.12/2016/2 (29 March 2017); UN Human Rights Committee, General comment No. 37 (2020) on the right of peaceful assembly (article 21)*, CCPR/C/GC/37 (17 September 2020); and UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, “Views adopted by the Committee under article 7 (3) of the Optional Protocol, concerning communication No. 130/2018,” CEDAW/C/78/D/130/2018 (18 February 2021). States have echoed these conclusions in recommendations made and accepted under the Universal Periodic Review,70Over 1,500 universal periodic review (UPR) recommendations made by countries from across all regions have referred to human rights defenders. (See UPR Info Database, https://bit.ly/3ImkYDe.) and also in voluntary pledges made by candidates campaigning for Human Rights Council membership.71See, for example, the voluntary pledge of Finland in its candidacy in 2021, A/76/93 (22 June 2021).

Key Commitments

Overview of Commitments

The key obligations of states72Many other actors, in particular UN entities, national human rights institutions, and businesses, are referred to in the instruments referenced in this section, and are called upon to take action to support state efforts to create safe and enabling environments for human rights defenders. in relation to human rights defenders are articulated in the Declaration on Human Rights Defenders. At the core of that instrument is the duty to protect, promote, and implement all human rights. At the same time, the Declaration and subsequent resolutions recognize that the achievement of human rights is impossible without the contribution of human rights defenders.73UN General Assembly Resolution 53/144, Art. 18; UN General Assembly Resolution 68/181, Promotion of the Declaration on the Right and Responsibility of Individuals, Groups and Organs of Society to Promote and Protect Universally Recognized Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms: protecting women human rights defenders (18 December 2013), para. 3; UN General Assembly Resolution 70/161, A/RES/70/161, para. 2; and UN General Assembly Resolution 72/247, A/RES/72/247 (24 December 2017), para. 2. Moreover, the right to defend human rights is recognized as an indispensable element in building and maintaining sustainable, open, and democratic societies.74UN General Assembly Resolution 53/144, A/RES/53/144, Art. 18; UN General Assembly Resolution 68/181, A/RES/68/181, para. 3; UN General Assembly Resolution 70/161, A/RES/70/161, para. 1; UN General Assembly Resolution 72/247, A/RES/72/247, para. 1; and UN Human Rights Council Resolution 31/32, A/HRC/RES/31/22, para. 1.

It is in this context that states have the overarching duty to defend the rights of individuals (working alone or with others) to promote human rights in their countries and globally.75UN General Assembly Resolution 53/144, A/RES/53/144, Art. 1. This obligation requires taking all measures necessary to create a safe and enabling environment, online and offline, in which all human rights defenders can operate free from hindrance and insecurity.76UN Human Rights Council Resolution 13/13, Protection of human rights defenders, A/HRC/RES/13/13 (25 March 2010), para. 2; UN Human Rights Council Resolution 22/6, Protection of human rights defenders, A/HRC/RES/22/6 (2013), para. 2; UN Human Rights Council Resolution 40/11, A/HRC/RES/40/11, para. 2 and 14(f); UN General Assembly Resolution 70/161, A/HRC/RES/70/161, para. 7; UN General Assembly Resolution 72/247, A/RES/72/247, para. 1; UN General Assembly Resolution 74/146, A/RES/74/146, para. 4 and 10; and UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174, para. 10. The main obligations of states in relation to human rights defenders are set out in the table below, with some examples of how commitments have been elaborated upon.77Many of these commitments and obligations have been examined in great detail by various human rights bodies, but it is not possible to provide a comprehensive list in the context of this issue brief. A very helpful resource examining international and regional duties is Esperanza Protocol/CEJIL, The International Legal Framework Applicable to Threats against Human Rights Defenders: A Review of the Relevant Jurisprudence in International Law (2021), https://cejil.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Protocolo-Esperanza-FINAL-051021.pdf.

| Core Duty/Commitment | Examples/Elaboration |

| Protect, promote, and implement all human rights78UN General Assembly Resolution 53/144, A/RES/53/144, Art. 2. | Ensure all persons under a state’s jurisdiction are able to enjoy all social, economic, political, and other rights and freedoms in practice.79Ibid., Art. 2(1). Adopt legislative, administrative, and other steps needed to ensure effective implementation of rights and freedoms.80Ibid., Art. 2(2). |

| Defend the rights of individuals (working alone or with others) to promote human rights in their countries and globally81Ibid., Art. 2. | International instruments consider democracy and rule of law to be essential components for the creation of a safe environment for human rights defenders (HRDs), to safeguard civic space, and to combat impunity for violations committed against HRDs.82UN General Assembly Resolution 74/146, A/RES/74/146, para. 7; and UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174, para. 13. Monitor efforts taken to implement the Declaration,83UN Human Rights Council Resolution 22/6, A/HRC/RES/22/6, para. 19. and strengthen data collection, analysis, and reporting on the situation of HRDs, including SDG Indicator 16.10.1.84Including reporting on killing, kidnapping, enforced disappearance, arbitrary detention, torture, and other harmful acts against human rights defenders, as reflected in Sustainable Development Goal indicator 16.10.1. UN General Assembly Resolution 68/181, A/RES/68/181, para. 22; UN General Assembly Resolution 74/146, A/RES/74/146, para. 19; and UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174, para. 25. Ensure legislation affecting HRD activities, and its application, is consistent with international human rights law,85UN Human Rights Council Resolution 22/6, A/HRC/RES/22/6, para. 3, 10, and 11; UN Human Rights Council Resolution 31/32, A/HRC/RES/31/32, para. 11-12; UN General Assembly Resolution 70/161, A/RES/70/161, para. 11; and UN General Assembly Resolution 74/146, A/RES/74/146, para. 4, 8, and 10. and that defenders’ work is not criminalized.86UN Human Rights Council Resolution 22/6, A/HRC/RES/22/6, para. 11; UN General Assembly Resolution 70/161, A/RES/70/161, para. 10(a); and UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174, para. 8 |

| Recognize the important and legitimate role of human rights defenders87UN Human Rights Council Resolution 31/32, A/HRC/RES/31/32, para. 7; UN Human Rights Council Resolution 40/11, A/HRC/RES/40/11, para. 2; UN General Assembly Resolution 74/146, A/RES/74/146, para. 2; and UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174, para. 1. | Publicly acknowledge this role in national and local statements, laws, policies, and programs.88UN Human Rights Council Resolution 13/13, A/HRC/RES/ 13/13, para. 4; UN Human Rights Council Resolution 22/6, A/HRC/RES/22/6, para. 5; UN Human Rights Council Resolution 31/32, A/HRC/RES/31/32, para. 4, UN Human Rights Council Resolution 40/11, A/HRC/RES/40/11, para. 6; UN General Assembly Resolution 70/161, A/HRC/RES/70/161, para. 4; UN General Assembly Resolution 72/247, A/HRC/RES/72/247, para. 4; UN General Assembly Resolution 74/146, A/RES/74/146, para. 8; and UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174, para. 14. Publicly condemn violence, discrimination, intimidation, and reprisals against HRDs, avoid stigmatizing their work, and respect the independence of their organizations.89UN Human Rights Council Resolution 22/6, A/HRC/RES22/6, para. 5; UN Human Rights Council Resolution 31/32, A/HRC/RES31/32, para. 6; UN Human Rights Council Resolution 40/11, A/HRC/RES/40/11, para. 6-10; UN General Assembly Resolution 74/146, A/HRC/RES/74/146, para. 8; and UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174, para. 14. |

| Ensure and support the creation and development of independent national institutions (such as national human rights institutions [NHRIs])90UN General Assembly Resolution 53/144, A/RES/53/144, Art. 14(c). | Support NHRIs91Established and operating in accordance with the Paris Principles. to play their role in monitoring existing legislation, providing input on draft legislation, and consistently informing the state about its impact on the activities of HRDs.92UN Human Rights Council Resolution 13/13, A/HRC/RES/13/13, para. 9, UN Human Rights Council Resolution 22/6, A/HRC/RES/22/6, para. 16 and 17; UN Human Rights Council Resolution 40/11, A/HRC/RES/40/11, para. 19; UN General Assembly Resolution 70/161, A/RES/70/161, para. 23; UN General Assembly Resolution 72/147, A/RES/72/147, para 17; and UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174, para. 21. NHRIs have also explored their mandate and responsibilities in this area. At the 13th International Conference of the Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions (GANHRI) in 2018, the “Marrakech Declaration” was adopted, focused on the role of NHRIs in expanding the civic space and promoting and protecting human rights defenders, with a specific focus on women. (Marrakech Declaration [2018], https://ganhri.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Marrakech-Declaration_ENG_-12102018-FINAL.pdf). NHRIs and their members and staff may sometimes be in need of protection.93UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174, para. 21. |

State Duty to Protect and Promote Specific Rights in Relation to HRDs:

| Core Duty/Commitment | Examples/Elaboration |

| Form associations and nongovernmental organizations94UN General Assembly Resolution 53/144, A/RES/53/144, Art. 5(b). | Ensure that any procedures governing the registration of civil society organizations are transparent, accessible, nondiscriminatory, expeditious, inexpensive, allow for the possibility to appeal and avoid requiring re-registration, and conform with international human rights law.95UN Human Rights Council Resolution 22/6, A/HRC/RES/22/6, para. 8; UN General Assembly Resolution 66/164, Promotion of the Declaration on the Right and Responsibility of Individuals, Groups and Organs of Society to Promote and Protect Universally Recognized Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, A/RES/66/164 (19 December 2011), para. 5; and UN General Assembly Resolution 70/161, A/RES/70/161, para. 10. Reporting requirements should not inhibit civil society organizations’ functional autonomy.96UN Human Rights Council Resolution 22/6, A/HRC/RES/22/6, para. 9(a). |

| Solicit, receive, and utilize resources97UN General Assembly Resolution 53/144, A/RES/53/144, Art. 13. | Refrain from discriminatorily imposed restrictions on potential sources of funding.98UN Human Rights Council Resolution 22/6, A/HRC/RES/22/6, para. 9(b). |

| Meet or assemble peacefully99UN General Assembly Resolution 53/144, A/RES/53/144, Art. 5(a). | Guarantee that in exercising this right, no person is subject to excessive and indiscriminate use of force; arbitrary arrest and detention; torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment; enforced disappearance; and the abuse of criminal and civil proceedings, or threats of such acts.100UN Human Rights Council Resolution 22/6, A/HRC/RES/22/6, para. 6; UN General Assembly Resolution 66/164, A/RES/66/164, para. 6; and UN General Assembly Resolution 68/181, A/RES/68/181, para. 8. See also UN Human Rights Council and General Assembly resolutions on the right to peaceful assembly and association, and reports of the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association. |

| Seek, obtain, receive, and hold information relating to human rights101UN General Assembly Resolution 53/144, A/RES/53/144, Art. 6. | Ensure transparent, clear, and expedient laws and policies that provide for a general right to request and receive information held by public authorities, including on human rights violations.102UN Human Rights Council Resolution 22/6, A/HRC/RES/22/6, para. 11; UN Human Rights Council Resolution 31/32, A/HRC/RES/31/32, para. 13; UN Human Rights Council Resolution 40/11, A/HRC/RES/40/11, para. 17; and UN General Assembly Resolution 70/161, A/RES/70/161, para. 10. |

| Submit to the authorities criticism and proposals103UN General Assembly Resolution 53/144, A/RES/53/144, Art. 8(2). and make complaints about official policies and acts104Ibid., Art. 9(3[a]). | Take the measures necessary to safeguard space for public dialogue on state policies and programs.105UN Human Rights Council Resolution 31/32, A/HRC/RES/31/32, para. 15; UN Human Rights Council Resolution 40/11, A/HRC/RES/40/11, para. 20; UN General Assembly Resolution 70/161, A/RES/70/161, para. 13; UN General Assembly Resolution 74/146, A/RES/74/146, para. 9; and UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174, para. 3. Form partnerships and collaboration between states, NHRIs, civil society, and other stakeholders.106UN General Assembly Resolution 72/247, A/RES/72/247, para. 5.. |

| Develop and discuss new human rights ideas and principles, and advocate their acceptance107UN General Assembly Resolution 53/144, A/RES/53/144, Art. 7. | Ensure legislation does not target activities of individuals and associations defending the rights of persons espousing minority beliefs,108UN Human Rights Council Resolution 22/6, A/HRC/RES/22/6, para. 11(h); and UN General Assembly Resolution 70/161, A/RES/70/161, para. 15. and that dissenting views can be expressed.109UN Human Rights Council Resolution 22/6, A/HRC/RES/22/6, para. 11(i). |

| Provide legal assistance,110UN General Assembly Resolution 53/144, A/RES/53/144, Art. 9(3[c]). and attend/monitor public hearings, proceedings, and trials111Ibid., Art. 9(3[b]). | Ensure HRDs are not harassed or prosecuted112UN Human Rights Council Resolution 22/6, A/HRC/RES/22/6, para. 10(d). for playing their valuable role in mediation efforts and supporting victims in accessing effective remedies.113UN Human Rights Council Resolution 31/32, A/HRC/RES/31/32, para. 10; and UN General Assembly Resolution 74/146, A/HRC/RES/74/146, para. 16. |

| Communicate without any restriction with nongovernmental and intergovernmental organizations (such as the UN114UN General Assembly Resolution 53/144, A/HRC/RES/53/144, Art. 9(4); UN Human Rights Council Resolution 22/6, A/HRC/RES/22/6, para. 13 and 14(a); UN Human Rights Council Resolution 40/11, A/HRC/RES/40/11, para. 12; UN General Assembly Resolution 68/181, A/HRC/RES/68/181, para. 18; UN General Assembly Resolution 70/161, A/HRC/RES/70/161, para. 16; UN General Assembly Resolution 72/247, A/HRC/RES/72/247, para. 8; UN General Assembly Resolution 74/146, A/HRC/RES/74/146, para. 5; and UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/HRC/RES/76/174, para. 6. State obligations in this area are further elaborated upon in UN Human Rights Council resolutions on cooperation with the United Nations, its representatives, and mechanisms in the field of human rights, as well as the annual reports of the UN Secretary General on the same topic, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Reprisals/Pages/Reporting.aspx) | Refrain from, and ensure adequate protection from, acts of intimidation or reprisals against those who cooperate, have cooperated, or seek to cooperate with international institutions, including their family members and associates.115UN Human Rights Council Resolution 22/6, A/HRC/RES/22/6, para. 14(a); UN General Assembly Resolution 68/181, A/RE/68/181, para. 17; and UN General Assembly Resolution 70/161, A/RES/70/161, para. 19(a). Bring perpetrators to justice and provide effective remedies for victims.116UN Human Rights Council Resolution 22/6, A/HRC/RES/22/6, para. 14(b); UN Human Rights Council Resolution 31/32, A/HRC/RES/31/32, para. 5; UN Human Rights Council Resolution 40/11, A/HRC/RES/40/11, para. 13; UN General Assembly Resolution 70/161, A/RES/70/161, para. 6, 18, and 19(b); UN General Assembly Resolution 72/247, A/RES/72/247, para. 8; UN General Assembly Resolution 74/146, A/RES/74/146, para. 5; and UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174, para. 6. |

| An effective remedy117UN General Assembly Resolution 53/144, A/RES/53/144, Art. 9. | Conduct prompt, effective, and impartial investigations of alleged violations of human rights and hold perpetrators to account,118Ibid.; UN Human Rights Council Resolution 13/13, A/HRC/RES/13/13, para. 12; UN Human Rights Council Resolution 31/32, A/HRC/RES/31/32, para. 6; UN Human Rights Council Resolution 40/11, A/HRC/RES/40/11, para. 10; UN General Assembly Resolution 66/164, A/RES/66/164, para. 8; and UN General Assembly Resolution 70/161, A/RES/70/161, para. 5. including public officials. 119UN Human Rights Council Resolution 22/6, A/HRC/RES/22/6, para. 11; and UN General Assembly Resolution 70/161, A/RES/70/161, para. 10(g). Put in place procedural safeguards, in accordance with international human rights law, to ensure the independence of the judiciary,120UN Human Rights Council Resolution 22/6, A/HRC/RES/22/6, para. 11(b). to protect the fair trial rights of HRDs, and to avoid the use of unreliable evidence, unwarranted investigations, and procedural delays.121Ibid., para. 11(c); and UN General Assembly Resolution 70/ |

| Effective protection under national law122UN General Assembly Resolution 53/144, A/RES/53/144, Art. 12(3). | Take all necessary measures to ensure the protection of HRDs, online and offline, against any violence, threats, retaliation, adverse discrimination, pressure, or any other arbitrary action as a consequence of their activities.123Ibid., Art. 12(2); UN Human Rights Council Resolution 13/13, A/HRC/RES/13/13, para. 6; UN Human Rights Council Resolution 40/11, A/HRC/RES/40/11, para. 1 and 8; UN General Assembly Resolution 66/164, A/RES/66/164, para. 3; UN General Assembly Resolution 70/161, A/RES/70/161, para. 8; UN General Assembly Resolution 72/247, A/RES/72/247, para. 9; UN General Assembly Resolution 74/146, A/RES/74/146, para. 1, 12, and 13; and UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174, para. 18. Do not use surveillance and information technologies against HRDs in a manner that is not compliant with international human rights law.124UN General Assembly Resolution 70/161, A/RES/70/161, para. 10(h); and UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174, para. 10 and 18. In meaningful consultation with HRDs,125UN Human Rights Council Resolution 13/13, A/HRC/RES/13/13, para. 5; UN Human Rights Council Resolution 31/32, A/HRC/RES/31/32, para. 8; UN Human Rights Council Resolution 40/11, A/HRC/RES/40/11, para. 9; UN General Assembly Resolution 70/161, A/HRC/RES/70/161, para. 13; and UN General Assembly Resolution 74/146, A/HRC/RES/74/146, para. 9 and 14. consider developing comprehensive, sustainable, appropriately resourced and age- and gender-responsive public policies or programs that comprehensively support and protect HRDs at risk or in vulnerable situations.126UN Human Rights Council Resolution 13/13, A/HRC/RES/13/13, para. 11; UN Human Rights Council Resolution 40/11, A/HRC/RES/40/11, para. 9; UN General Assembly Resolution 70/161, A/RES/70/161, para. 12; UN General Assembly Resolution 74/146, A/RES/74/146, para. 14 and 18; and UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174, para. 20 and 22. Take timely and effective action to respond to attacks or threats against HRDs, including through early warning and rapid response systems.127UN Human Rights Council Resolution 13/13, A/HRC/RES/13/13, para. 6; and UN Human Rights Council Resolution 40/11, A/HRC/RES/40/11, para. 9. Protection measures should be holistic and respond to the protection needs of individuals and the communities in which they live. Measures should address causes of attacks.128UN Human Rights Council Resolution 40/11, A/HRC/RES/40/11, para. 9; UN General Assembly Resolution 74/146, A/RES/74/146, para. 18; and UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174, para. 22. |

Applying State Commitments to Specific Groups of Defenders and Particular Contexts

The obligations and commitments above have been referred to in relation to specific groups of defenders, such as human rights defenders in armed conflict and post-conflict situations,129UN General Assembly Resolution 66/164, A/RES/66/164, para. 4; see also UN General Assembly, Human rights defenders operating in conflict and post-conflict situations. anti-corruption defenders,130UN Human Rights Council Resolution 31/32, A/HRC/RES/31/32, para. 14; and UN Human Rights Council Resolution 40/11, A/HRC/RES/40/11, para. 15. and young people and children.131UN Human Rights Council Resolution 40/11, A/HRC/RES/40/11, para 14(e); UN General Assembly Resolution 74/146, A/HRC/RES/74/146, para. 18; and UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174, para. 12. Some groups, such as women human rights defenders, have been the focus of UN resolutions, with states committing to apply a gender perspective,132UN Human Rights Council Resolution 22/6, A/HRC/RES/22/6, para. 12; UN Human Rights Council Resolution 31/32, A/HRC/RES/31/32, para. 9; UN Human Rights Council Resolution 40/11, A/HRC/RES/40/11, para. 11; UN General Assembly Resolution 68/181, A/RES/68/181, para. 5; UN General Assembly Resolution 70/161, A/RES/70/161, para. 14; UN General Assembly Resolution 72/247, A/RES/72/247, para. 11; UN General Assembly Resolution 74/146, A/RES/74/146, para. 6; and UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174, para. 5 and 11. and to ensure that protection policies and measures are gender-responsive.133See UN General Assembly Resolution 68/181, A/RES/68/181, para. 19 and 20. Other resolutions have highlighted the intersectional dimensions of violations and abuses against women human rights defenders, Indigenous peoples, children, persons with disabilities, persons belonging to minorities, and rural communities.134UN General Assembly Resolution 74/146, A/RES/74/146, para. 18; and UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174, para. 22. Such references and commitments represent important advances in resolutions at the UN in terms of acknowledging and addressing the differentiated needs of groups of defenders. This progress could be built upon by integrating knowledge and experience gained at the national, regional, and international levels.135Achievements in these have been driven by research, analysis, and advocacy by civil society. See, for example, publications of Amnesty International, Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development, Association for Women’s Rights in Development, Center for Justice and International Law, Defend Defenders, Front Line Defenders, Global Witness, IM-Defensoras, International Federation for Human Rights, International Service for Human Rights, Just Associates, Peace Brigades International, Protection International, and Transparency International. See also the work of the UN and regional rapporteurs on human rights defenders, and the jurisprudence of the regional human rights mechanisms.

Economic, Social, Cultural, Environmental, Land, and Indigenous Rights Defenders

Economic, social, cultural, environmental, land, and Indigenous rights defenders136This grouping includes an overlapping and wide range of human rights defenders who have been found to share similar risks and challenges. See also UN Human Rights Council Resolution 31/32, A/HRC/RES/31/32, para. 1-2. face high risks as a consequence of their work, and the situation and protection needs of these rights defenders have been highlighted in different resolutions.137Including UN General Assembly Resolution 70/161, A/RES/70/161; UN General Assembly Resolution 72/247, A/RES/72/247; UN General Assembly Resolution 74/146, A/RES/74/146; UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174; UN Human Rights Council Resolution 31/32, A/HRC/RES/31/32; and UN Human Rights Council Resolution 40/11, A/HRC/RES/40/11. States have condemned all human rights violations or abuses against environmental and Indigenous human rights defenders.138UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174, para. 5. States have also committed to combating the impunity of perpetrators of these acts.139Ibid.

States recognize the work of these defenders as a vital factor contributing to the realization of environmental, land, and Indigenous rights, including as they relate to development and corporate accountability.140UN General Assembly Resolution 70/161, A/RES/70/161, para. 9; UN General Assembly Resolution 72/247, A/RES/72/247, para. 10; UN General Assembly Resolution 74/146, A/RES/74/146, para. 22; and UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174, para. 23. States also take account of the important role human rights defenders play in the empowerment and capacity-building of Indigenous peoples.141UN Human Rights Council Resolution 40/11, A/HRC/RES/40/11, para. 16. In this context, resolutions have noted states’ duties to disclose environmental data and information related to environmental decision-making,142Ibid., para. 14 and 18. and in the context of combatting corruption.143Ibid., para. 15. In addition, states have emphasized the legitimate role of defenders in mediation and in supporting victims to access remedies. 144UN Human Rights Council Resolution 31/32, A/HRC/RES/31/32, para. 10; UN General Assembly Resolution 74/146, A/RES/74/146, para. 16; and UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174, para. 17.

Recognizing the involvement of businesses in the targeting of such human rights defenders, states have highlighted their duty to implement the UN’s Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.145UN, Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: Implementing the United Nations “Protect, Respect and Remedy” Framework(2011), https://www.ohchr.org/documents/publications/guidingprinciplesbusinesshr_en.pdf; UN General Assembly Resolution 74/146, A/RES/74/146, para. 21; UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174, para. 26; and UN Human Rights Council Resolution 40/11, A/HRC/RES/40/11, para. 21. These principles underscore the responsibility of all business enterprises to respect the rights to life and to the liberty and security of human rights defenders, and their exercise of the rights to freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and association, and participation in the conduct of public affairs.146UN General Assembly Resolution 74/146, A/RES/74/146, para. 21; and UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174, para. 22. Seeking to protect defenders from abuses by business enterprises, states have committed to engaging in initiatives to promote effective prevention, accountability, remedy, and reparations.147UN Human Rights Council Resolution 31/32, A/HRC/RES/31/32, para. 19.

State obligations have also been applied to particular contexts, such as counterterrorism, 148UN Human Rights Council Resolution 22/6, A/HRC/RES/22/6, para. 10; UN General Assembly Resolution 66/164, A/HRC/RES/66/164, para. 7; UN General Assembly Resolution 70/161, A/RES/70/161, para. 10(c); and UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174, para. 8. and to country situations.149See, for example, UN Human Rights Council Resolution 46/20, Situation of human rights in Belarus in the run-up to the 2020 presidential election and in its aftermath, A/HRC/RES/46/20 (24 March 2021). For example, the most recent resolution at the General Assembly included a focus on the COVID-19 pandemic and related emergency measures.150UN General Assembly Resolution 76/174, A/RES/76/174.

This resolution recognizes that the pandemic has exacerbated and accelerated existing challenges, both online and offline, for human rights defenders. States have committed to ensuring that COVID-19-related emergency measures are not misused to endanger the safety of human rights defenders, or to unduly hinder their work in a manner contrary to international law.

In addition, states recognized the valuable contribution of human rights defenders in identifying and raising awareness of the human rights impacts of COVID-19 response and recovery measures. This contribution is possible if defenders are able to freely express their views, concerns, support, criticism, or dissent regarding government policy. Defenders were highlighted as being critical to providing accurate information about the situation and needs on the ground, and to contributing to designing and implementing responsive measures. In this context, states committed to safeguarding space for such public dialogue, and took note of the guidance of the Secretary-General and the High Commissioner for Human Rights on human-rights-compliant responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Opportunities to Strengthen Commitments on Human Rights Defender Protection

The fundamental responsibilities of states in relation to human rights defenders are clearly enshrined in international instruments and in many recommendations for state action by UN experts, as well as in some state policies. Despite this, the situation for human rights defenders of diverse identities working across a wide range of topics around the globe remains challenging, and sometimes lethal. The Special Rapporteur has pointed to many reasons, including a lack of political will to create safe and enabling environments, state criminalization of defenders and their actions, impunity for those who target defenders, ineffectiveness and under-resourcing of national mechanisms and bodies, and corruption and the influence of powerful groups. Almost 25 years since the adoption of the Declaration of Human Rights Defenders, more effective action is needed to ensure its implementation.

While states have continued to affirm commitments to the protection of human rights defenders, many more opportunities exist for states to further implementation within their own jurisdictions, to support other states in their efforts to do the same, to push for accountability where violations occur, and to further enhance the international framework for defender protection. The goal of these efforts is to create safe and enabling environments for human rights defenders to perform their activities – to make sure defenders are able to do their vital work without fear. This objective can only be achieved if defenders – real individuals, groups, and communities – are safe in practice.

Whether in national or international efforts, it is essential that states work in partnership with human rights defenders. States must consult meaningfully with civil society so that any efforts to ensure the protection of human rights defenders are designed to effectively address existing concerns and to support concrete improvements in the situation of defenders. Human rights defenders should also be involved in the implementation of any protection policies, measures, or actions.

Risks

Some states continue to challenge key elements of resolutions on or referring to human rights defenders. As a result, member states have to manage a number of risks if they wish to advance efforts to protect human rights defenders within the UN framework and at home. Two major risks relate to member state dynamics and the issue of consensus.

Member state dynamics. While much has changed geopolitically since the adoption of the Declaration on Human Rights Defenders, the essential points of contention, and even some of the key states opposing UN action151States that have taken leading roles in proposing or supporting amendments that would weaken draft resolutions on human rights defenders include China, Cuba, Egypt, and Russia. on human rights defenders, remain similar. States seeking to defend and advance international standards in this area must be able to contend with very vocal and mobilized opposition.

During negotiations, amendments are consistently proposed by states where defenders are frequently reported to be targeted. 152See, for example, the joint civil society letter to member states of the UN Human Rights Council, “Re: Support resolution on the protection of human rights defenders addressing economic, social and cultural rights,” March 22, 2016, https://ishr.ch/sites/default/files/article/files/letter_to_member_states_of_the_unhrc_hrds_04_04_16_0.pdf. The proposals are generally ones that would have the effect or aim of denying the legitimacy of human rights defenders, failing to acknowledge the specific risks and violations faced by certain groups of defenders, diluting and regressing consensus language from previous resolutions, and seeking to justify limitations on human rights that are impermissible under international human rights law.153See, for example, ibid. These opposing states make arguments related to the primacy of state sovereignty; the need for defenders to act in accordance with a country’s morals and customs; the risk of creating new rights; and the very use and definition of the term “human rights defender.” In addition, some states that support resolutions on human rights defenders can hold positions that run counter to the goals of such instruments, for example in the context of arguments on national security and surveillance, or business and human rights.

Prioritizing consensus over progress. Consensus in adopting UN resolutions is seen to strengthen the weight of the instrument and show universal support for its contents. However, the value of consensus can be greatly reduced in some cases, for example if consensus prevents efforts to make substantial progress and has the impact of working against the spirit of the resolution; if it leads to the inclusion of language and concepts not aligned with or misrepresenting international standards; or if states disassociate themselves with key aspects of the text during its adoption. These are all issues that states must contend with in the context of resolutions on human rights defenders.154See, for example, discussions in International Service for Human Rights, “UNGA 72: Third Committee Adopts Resolution on Human Rights Defenders by Consensus” November 21, 2017, https://ishr.ch/latest-updates/unga-72-third-committee-adopts-resolution-human-rights-defenders-consensus/; International Service for Human Rights, “UNGA76: Third Committee Acknowledges Human Rights Defenders’ Critical Role in Pandemic Responses” 2021, https://ishr.ch/latest-updates/unga76-third-committee-acknowledges-human-rights-defenders-critical-role-in-pandemic-responses/; and International Service for Human Rights, “HRC40: Council Unanimously Recognises Vital Role of Environmental Human Rights Defenders” 2019, https://ishr.ch/latest-updates/hrc40-council-unanimously-recognises-vital-role-environmental-human-rights-defenders/. Reiterations of previous commitments can help to cement these and reinforce international standards, but if those standards are not being implemented, as is the case regarding human rights defender protection, it may be necessary to consider more ambitious instruments adopted by a vote. In all action on this issue at the UN, the goal should be outcomes that would have the greatest real-world impacts on the situations of defenders. To identify what measures would achieve this goal, states must consult with human rights defenders.

Opportunities

A state’s first opportunity, and priority, must be implementation of the Declaration and related international standards within its own jurisdiction. This requires working with civil society, NHRIs, and other stakeholders to identify existing gaps and weaknesses and to develop a road map to address them. In this context, some countries have introduced laws and policies to recognize and protect human rights defenders,155See, for example, Cote d’Ivoire, Burkina Faso, and Mali. (International Service for Human Rights, “Côte d’Ivoire: Civil Society Welcomes Government Decree to Protect Defenders, Urges Adequate Resourcing,” May 22, 2017, https://ishr.ch/latest-updates/cote-divoire-civil-society-welcomes-government-decree-to-protect-defenders-urges-adequate-resourcing/; International Service for Human Rights, “Burkina Faso: Implementation of the Defenders’ Law Must Be a Priority,” June 10, 2021, https://ishr.ch/latest-updates/burkina-faso%E2%94%82implementation-of-the-defenders-law-must-be-a-priority/; and Front Line Defenders, “The Council of Ministries Adopts the Implementation Decree on the Law on Protection of Human Rights Defenders,” February 24, 2020, https://www.frontlinedefenders.org/en/statement-report/council-ministries-adopts-implementation-decree-law-protection-human-rights.) It should be noted that implementation of the Declaration of Human Rights Defenders does not require the adoption of such laws or policies. and some national mechanisms have been established to prevent and respond to risks and attacks.156UN Human Rights Council, A/HRC/46/35, 5 and 18. However, advocates in these countries raise concerns about under-resourcing and a lack of political will to implement the instruments and support the mechanisms,157Ibid. See also Center for Justice and International Law (CEJIL) and Protection International, The Time is NOW for Effective Public Policies to Protect the Right to Defend Human Rights, (2018), https://www.protectioninternational.org/sites/default/files/20180620_The%20time%20is%20NOW.pdf. with defenders continuing to be threatened and killed.158Global Witness, Last Line of Defence: The Industries Causing the Climate Crisis and Attacks against Land and Environmental Defenders, (2021), https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/environmental-activists/last-line-defence/, 11. A related step, which would also support efforts to assist other states seeking to address defender protection issues, could be to develop indicators to assess implementation of the Declaration.

Using Diplomatic Relations to Protect Human Rights Defenders

As part of their commitments to human rights defender protection, states should develop strategies to encourage or support better implementation of the Declaration on Human Rights Defenders in countries with which the state has strong diplomatic relations. Such engagement can be led by the development and operationalization of national or regional guidelines on supporting human rights defenders,159Some states and bodies have developed such guidelines, such as the European Union, Canada, Finland, the Netherlands, Norway, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America. In this context, see Amnesty International, Defending Defenders? An Assessment of EU Action on Human Rights Defenders, (2019), https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/ior60/0995/2019/en/. See also tools for diplomats developed by the International Service for Human Rights, https://ishr.ch/defenders-toolbox/resources/strengthening-diplomatic-initiatives-for-the-protection-of-human-rights-defenders-2/. and the inclusion of civic space and human rights defender protection issues in bilateral and human rights dialogues. Diplomatic missions can also support local efforts to enhance civic space and strengthen civil society.

In the context of UN mechanisms, states should provide information to the UN on steps taken to implement the Declaration, in particular on SDG reporting and SDG Indicator 16.10.1. In addition, states are urged to implement recommendations of the Secretary-General in relation to reprisals, in particular to fully investigate any alleged cases of reprisals and hold the perpetrators to account. States should also cooperate fully with, and adequately resource, the mandates of the Special Rapporteurs on human rights defenders of the UN, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Cooperation includes implementation of the recommendations made to states in reports and communications,160While the UN Special Rapporteur receives substantive replies to slightly less than half of the communications it sends to states, a large number of the communications are “follow-up” communications, concerning fresh allegations against defenders who have already been the subject of previous communications. See, for example, UN General Assembly, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, Observations on communications transmitted to governments and replies received, A/HRC/46/35/Add.1 (15 February 2021), https://undocs.org/A/HRC/46/35/ADD.1, 3-4. and issuing invitations for country visits.161The UN Special Rapporteur has received no response to recent/active requests for invitations made to at least 12 states. (See UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Special Procedures Country Visit database, https://spinternet.ohchr.org/ViewMandatesVisit.aspx?visitType=all&lang=En.)

There are many other avenues for states to support international efforts to build safe and enabling environments for human rights defenders. Below are three approaches that the UN could take.