Introduction

The 2022 war and humanitarian crisis in Ukraine have brought the future of conflict into stark reality: Both hybrid and conventional military capabilities will be used to target populations and damage urban centers with the aim of weakening political resolve. Reverberations of the crisis will be felt across Europe for decades, reaffirm NATO’s focus on collective defense, and potentially expand its membership to include Sweden and Finland. While the rapid political, military, and humanitarian response is laudable, whether a more coordinated strategy could have pre-empted the need for these responses remains an open question. In particular, the initial NATO response was reactionary, despite two NATO-specific policies in place since 2016: Resilience and the Protection of Civilians. Both were designed to help understand and mitigate conflict-related impacts on civilians, albeit from different perspectives. Responding to this new and still-changing threat environment will require NATO to embrace an innovative approach connecting civil preparedness and military response at all levels.

These considerations are relevant within the context of future urban conflict that will inevitably occur, and where the interconnectivity between resilience factors (for both civil society and military forces) and the need to mitigate civilian harm is most profound. As NATO defines its new strategic concept1 Note: NATO’s Strategic Concept is “a key document for the Alliance. It reaffirms NATO’s values and purpose and provides a collective assessment of the security environment. It also drives NATO’s strategic adaptation and guides its future political and military development. Since the end of the Cold War, it has been updated approximately every 10 years to take account of changes to the global security environment and make sure the Alliance is prepared for the future.” “NATO 2022 – Strategic Concept,” NATO, n.d., https://www.nato.int/strategic-concept/index.html. and emphasizes collective defense, it is critical that NATO learn from the Ukraine conflict, address the broader challenges to human security2 Note: Human Security (HS) was first introduced as a term in 1994 by the UNDP Global Human Development Report. “Human Development Report 1994” (New York: United Nations Development Programme, 1994), https://www.hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/reports/255/hdr_1994_en_complete_nostats.pdf. It is broadly defined as freedom from want, fear, and indignity. In 2012, UN General Assembly adopted a standard definition. “A/RES/66/290 Follow-up to Paragraph 143 on Human Security of the 2005 World Summit Outcome,” un.org, United Nations, September 10, 2012, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N11/476/22/PDF/N1147622.pdf?OpenElement. The protection of civilians is an integral part of NATO’s human security approach. The latter approach is premised on understanding HS related to the “risks and threats to populations where NATO has operations, missions or activities” and mitigation and response measures. “Human Security,” NATO, March 11, 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_181779.htm. , and focus on more than just military action. Doing so will require a comprehensive blend of activities, from strategy to tactics. The scope is broad; however, this paper discusses the NATO imperative to include human security by fully integrating resilience and protection of civilians. Doing so will enhance the Alliance’s ability to anticipate, prepare, and, when needed, respond to future security threats.

The Future Operating Environment

The operating environment has changed significantly since NATO last updated its Strategic Concept in 2010. In that document, the focus was on out-of-area security and stability. Events over the past dozen years and those playing out today have driven greater emphasis on collective defense. The new strategic concept, expected to be presented at the 2022 Summit in Madrid, will undoubtedly focus on Article 5 and reflect the new reality in Europe. This new defense and security paradigm will have echoes of the Cold War, such as the current increase in troop numbers based in Europe. It will also embrace the profound technological, economic, and societal changes of the past three decades. As with the earlier forward basing of forces in West Germany, NATO’s increasing military presence and posture on its eastern periphery will need to provide credible deterrence. However, threats are broader than just that of direct military action. Globalized and more open markets offer opportunities, dependencies, and vulnerabilities that affect societies and create security challenges. Technology connectivity is a vital element of everyday life, and access to information is a democratic right., However, this situation affords adversaries far greater reach into societies than ever before. There are enduring physical and moral challenges, too. Developments in Ukraine have provided NATO with insight into the realities of future conflict that it must prepare to meet. With millions of displaced persons so far, the destruction of cities, and rising civilian deaths3 Note: As of 30 May 2022, the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) recorded 8,900 civilian casualties in the country: 4,074 killed and 4,826 injured. “Ukraine – Civilian Casualty Update,” United Nations, May 30, 2022, https://ukraine.un.org/sites/default/files/2022-05/Ukraine%20-%20civilian%20casualty%20update%20as%20of%2024.00%2029%20May%202022%20ENG.pdf. , the need to anticipate such situations and mitigate them could not be more clear.

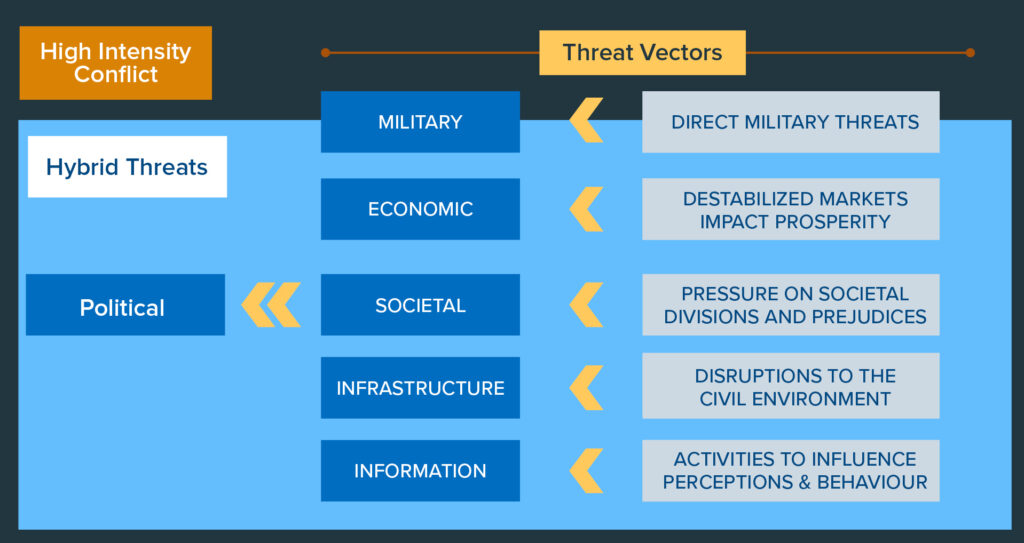

Understanding the threat vectors and impact on society through the inclusion of the Protection of Civilians and Resilience measures will support the inclusion of Human Security, enhancing NATO’s future strategies.

The current and future character of conflict and warfare is marked by simultaneous disruptive activities against governments, industries, economies, and societies, traditional coercive military posturing, and acts of violence and aggression. As part of these hybrid strategies, the interconnectedness of societies and cultures is purposely targeted to amplify tensions and challenge governments4 Note: This is one of the challenges of ‘Societal Resilience.’ As seen in the Stable State model (AJP 3.4.5), one of the five areas of a Stable State is ‘Societal Relationships.’ This is one area that is susceptible to attack that falls short of an Article 5 violation . The displacement and movement of people are used as a wave to break on neighboring states, straining economic and social systems and raising tensions. This impedes states’ freedom to physically and politically maneuver when conflict does arrive. During conflict and crisis, the focus is often on the military; however, within civil society, threats will converge to generate strategic pressure and constrain political and military freedoms to act.

There is a broad consensus that the future operating environment will be congested, cluttered, contested, connected, and constrained5 Note: “Strategic Trends Programme: Future Operating Environment 2035” (UK Ministry of Defence, December 14, 2015), https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1076877/FOE.pdf. . Adversaries will look for opportunities to undermine cohesion, using physical, virtual, and cognitive activities6 Note: Allied Joint Publication AJP 3-10 defines the Information Environment as including three inter-related domains: Physical, Virtual and Cognitive. to gain political advantage. The effects of these activities are channeled and felt through societies. Understanding civil and societal vulnerabilities and having strategies that assess, build, and enhance resilience must be a critical element in operational planning for future crises and conflicts.

UN data indicates that more than half of the world’s population lives in towns and cities. By 2050, the global urban population will grow by another 3 billion7 Note: “Urbanization,” United Nations Population Fund, accessed April 30, 2022, https://www.unfpa.org/urbanization. . Given that conflict and warfare are human afflictions and cities are political and economic centers, it is a fallacy to think that urban conflict can be avoided. Urban centers will be the targets of future disruptions.8 Note: Ukraine being a case in point with conflict unfolding in densely populated urban areas, leading to (rising) civilian deaths, displacement, and refugee flows of millions of people, alongside destruction of cities. Urban centers are highly susceptible to these attacks9 Note: Cities are dependent on the inflow of basic needs, generate the most displacement and are the environments where most civilian harm occurs. ,10 Note: By 2050, 68.4 percent of the world’s population is expected to live in cities. “Percentage of Population at Mid-Year Residing in Urban Areas by Region, Subregion, Country and Area, 1950-2050” (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2018), https://population.un.org/wup/Download/. and recent conflicts11 Note: Kiev, Mariupol (2022), Aleppo (2012–2016), Mosul (2014–2017), Grozny (1999–2000). have proven that cities are the most demanding environments where NATO forces will have to operate. The inflow of displaced people stresses the systems as much as the destruction of medical facilities or food distribution centers, rapidly creating humanitarian crises that must be addressed concurrently with military operations. These aspects influence the shape of military operations as much as adversaries’ size, strength, and intentions. Consequently, NATO must ensure that its Resilience and Protection of Civilians policies are not viewed as optional or stand-alone but are integrated as much-needed contributions to the operational planning process.

Resilience

Within discussions on sustainable and inclusive security, the applicability of the concept of resilience often stumbles over a conflation of terms and objectives. However, a more nuanced examination reveals another possibility—while not the only tool in the security toolbox, resilience may serve multiple purposes within various contexts. The key to understanding resilience is reckoning with its complexity.12 Note: Gergana Vaklinova, “Tracing Resilience: A Context of Uncertainty, a Trajectory of Motion,” CMDR COE Proceedings 2019, 2019, 5–38.

It is essential across different fields of knowledge and practice to understand what or who is to be resilient, against which risks and threats, and how to build and sustain resilience.

The concept of resilience is a fusion of ideas from various disciplines13 Note: For instance, ecology, engineering, psychology, and behavioral science. with application conditioned upon a contextualization that focuses on subjects, objects, interactions, relations, and objectives. It is essential across different fields of knowledge and practice to understand what or who is to be resilient, against which risks and threats, and how to build and sustain resilience. This conceptual compass enables an operationalization consistent with specific requirements and seeks to inform practical solutions in the face of disruptions.14 Note: Disruption is a cumulative term encompassing a continuum from mild stresses to significant shocks. While the objectives of resilience (augmented prevention, bounce back, adaptation, transformation) are not foreign to security and defense, the concept’s application is novel in the expression it acquires within a Human Security approach and in the realization that resilience is not an end state but rather a comprehensive and multidimensional process. The success of the latter method is underpinned by the viability of relations and the persistence of connectedness.

Resilience has been a central pillar of total defense15 Note: An approach to security positing a whole-of-society (armed forces, civil administrations, private sector, and the public) engagement and collaboration under the control of democratic political authorities. , a concept developed during the Cold War and encapsulating a state-centric (territorial integrity, sovereignty) approach to security in the event of a military attack. Only after 1990 was the concept re-focused to anchor disaster management16 Note: The disaster management cycle includes preparedness, response, recovery, and reconstruction as separate yet closely interlocked phases. “Disaster and Disaster Response,” CMDR COE, n.d., https://www.cmdrcoe.org/menu.php?m_id=113. in civil preparedness. It is currently being revisited17 Note: Notably, Estonia, Norway (NATO members), Sweden, Finland, Switzerland (partner countries), and other nations like Singapore. For elaboration on the specificities of each country’s approach to defining and applying total defense. Joëlle Garriaud-Maylam, “Enhancing the Resilience of Allied Societies Through Civil Preparedness” (NATO Parliamentary Assembly, October 9, 2021), https://www.nato-pa.int/document/2021-enhancing-resilience-allied-societies-through-civil-preparedness-garriaud-maylam. to introduce an all-hazards lens to a revitalized whole-of-society approach. This additional Human Security-related lens is an essential aspect of resilience as individuals, communities, states, the private sector, organizations, and their connectedness should simultaneously be resilient (anticipate, prevent, respond, recover, and transform) in times of disruption.

In interdependent environments, especially in urban contexts, threats manifest in intricate constellations and are likely to cascade across multiple domains (see Figure 1). Resilience allows for understanding challenges and opportunities deriving from systemic openness and interdependence and offers a look beyond a classical adversarial analysis. Analytically, that means a focused examination of critical vulnerabilities across various domains and at multiple levels18 Note: Which may be exploited to worsen tensions further and/or erode trust in and legitimacy of actions taken. and identification of specific needs19 Note: Applying a gender perspective allows for an intersectional analysis that investigates the needs of women, men, boys, and girls seeking differences and similarities. On NATO’s commitment to and policy, direction, and guidance on the integration of gender perspectives, see: NATO/EAPC Policy and Action Plan on the Implementation of the Women, Peace and Security Agenda: https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/pdf_2018_09/20180920_180920-WPS-Action-Plan-2018.pdf; NATO Bi-Strategic Command Directive 40-1: Integrating Gender Perspective into the NATO’s Command Structure: https://www.act.nato.int/application/files/3916/3842/6627/Bi-SCD_040-001.pdf alongside existing capacities and capabilities. Practically, resilience is a benchmark for assessing how much stress a state can bear and distribute across its constitutive elements while preserving and adapting critical functions, as well as how much pressure would cause a society to sustain or withdraw support for government strategies, policies, and actions.

The application of the concept of resilience emerges as a critical measure against hybrid threats. If hybrid strategies seek to undermine societies’ security and stability while applying pressure from within, then identifying existing vulnerabilities and potential fault lines to build resilience against risks and threats would be a prudent undertaking. A comprehensive understanding of the human environment will enhance the analysis of existing capacities and inform tailored measures to protect civilians. Ideally, establishing a resilient society will prevent disruption in the first place or at least mitigate its impacts while accelerating recovery through adaptation or transformation.

Resilient societies have a crucial role in deterrence and defense as they provide critical support in both times of peace and crisis. Resilient communities provide “a less attractive target for malicious outside actors,”20 Note: Garriaud-Maylam, “Enhancing the Resilience of Allied Societies Through Civil Preparedness.” which significantly increases the cost of victory and reduces the chances of adversarial success. Moreover, resilient societies have an enhanced cognition of risks and threats and fewer divisive lines that may transform into critical vulnerabilities if exploited by malicious actors. They also have an increased capacity and willingness to contribute to collective prevention and protection efforts.

A resilient society is foundational to both human security and the protection of civilians. However, this depends on a whole-of-government capacity to build trust, communicate, and converge around core principles and values. Societal and democratic resilience,21 Note: For an account of democratic resilience within NATO, see “Resolution 466: Developing a Whole-of-Society, Integrated and Coordinated Approach to Resilience for Allied Democracies” (NATO Parliamentary Assembly, October 11, 2021), https://www.nato-pa.int/download-file?filename=/sites/default/files/2021-10/2021%20-%20NATO%20PA%20Resolution%20466%20-%20Resilience_0.pdf. emphasizing human rights and the rule of law, are part of the overall resilience equation. Resilient democracies ensure a continuous, transparent, and trustworthy relationship between people and institutions and guard against disturbances like disinformation.22 Note: For a discussion on democratic resilience and disinformation, consult the special report to the NATO Parliamentary Assembly. Linda Sanchez, “Bolstering the Democratic Resilience of the Alliance Against Disinformation and Propaganda” (Committee on Democracy and Security (CDS): NATO Parliamentary Assembly, October 10, 2021), https://www.nato-pa.int/download-file?filename=/sites/default/files/2021-10/013%20CDS%2021%20E%20rev.%202%20fin%20-%20DEMOCRATIC%20RESILIENCE%20-%20SANCHEZ.pdf. Trust is a fundamental aspect of democratic resilience and a magnifying factor for societal resilience. High levels of trust and confidence consolidate political and societal cohesion and coalesce collective efforts in times of hardship.

NATO’s Approach

Resilience for NATO is both a national responsibility and a collective commitment. At the 2021 Brussels Summit, NATO leaders agreed to the 2030 Agenda to strengthen the Alliance over the next decade and beyond.23 Note: “Brussels Summit Communiqué Issued by the Heads of State and Government Participating in the Meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Brussels,” NATO, June 14, 2021, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_185000.htm. A vital aspect of the plan is the continued strengthening of resilience for effective collective defense and deterrence in the face of increased hybrid threats. As a political and military alliance with the stated goal of ensuring its citizens’ protection and promoting security and stability in the North Atlantic area, NATO cohesion is contingent upon high levels of resilience within each Member State and across the Alliance and its Partners. Understanding resilience and connecting its requirements to the protection of civilians informs an all-hazard approach to security.

The principle of resilience is anchored in Article 3 of NATO’s founding treaty, which stipulates that “[i]n order more effectively to achieve the objectives of this Treaty, the Parties, separately and jointly, by means of continuous and effective self-help and mutual aid, will maintain and develop their individual and collective capacity to resist armed attack.”24 Note: “The North Atlantic Treaty” (NATO, April 4, 1949), https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_17120.htm. Since then, the concept has evolved into one of national resilience through civil preparedness25 Note: “The capacity of each member nation to “resist and recover from a major shock such as a natural disaster, failure of critical infrastructure, or a hybrid or armed attack.” “Resilience and Article 3,” NATO, June 11, 2021, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_132722.htm. that synergizes with and enhances the Alliance’s capacity to prevent, protect, adapt, and transform.

In future conflicts, NATO will likely engage with adversaries who look to undermine the Alliance with increasingly sophisticated strategies, often through coordinated political, military, economic, cyber, and information efforts26 Note: Rear Admiral John W. Tammen, “NATO’s Warfighting Capstone Concept: Anticipating the Changing Character of War,” NATO Review, July 9, 2021, https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2021/07/09/natos-warfighting-capstone-concept-anticipating-the-changing-character-of-war/index.html. . Resilience is an essential component of countering such strategies, and the Alliance has identified it as one of its future warfare development imperatives. The NATO Warfighting Capstone Concept (NWCC)27 Note: NWCC offers a threat-informed vision of challenges and details how NATO Allies must develop their militaries to maintain advantage for the next twenty years. Tammen, “NATO Review – NATO’s Warfighting Capstone Concept.” develops a layered approach to resilience whereby different layers28 Note: Military resilience, military-civil resilience, and civilian resilience. “The NATO Warfighting Capstone Concept: Key Insights from the Global Expert Symposium Summer 2020” (Global Expert Symposium, The Hague: The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, 2020), 12, https://hcss.nl/wp-content/uploads/attachments/NATO_Symposium_Final_Version_For_Publication.pdf. interact29 Note: Civil-military cooperation is essential for resilience as it allows for trust to evolve from a mutual understanding of requirements and capabilities. and reinforce the military instrument of power. Effectively, this distributive approach to resilience reckons with “interdependencies between Allies, across instruments of power, between public and private [sectors], and across the military services”30 Note: Davis Ellison, “Mastering the Fundamentals: Developing the Alliance for the Future Battlefield,” The Three Swords, October 2021, https://jwc.nato.int/download_file/view/1643/277. and shares the burden of preparedness, response, adaptation, and transformation.

Resilience is an essential component of countering hybrid strategies and has been identified as one of the future warfare development imperatives for the Alliance.

NATO has recognized the close relationship between resilience and deterrence and the role of societies31 Note: Society is a system of individuals, civil structures, resources, services, and relations. as a “first line of defense.”32 Note: Wolf-Diether Roepke and Hasit Thankey, “Resilience: The First Line of Defence” (Defence Policy and Planning Division – NATO Headquarters, February 2019), https://www.jwc.nato.int/images/stories/_news_items_/2019/three-swords/ResilienceTotalDef.pdf. Moreover, in addition to states, societies, and the military, the private sector is an essential component of resilience. Governments and armed forces depend significantly on the commercial sector for transport, communications, and basic supplies.33 Note: NATO, How Does NATO Support Allies’ Resilience and Preparedness?, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zV-lGVupAv4. In times of disruption, both the demand and the pressure on supply increase, especially in urban environments.34 Note: That heavily rely on external supplies of goods and services. Therefore, ensuring that these sectors and—critically—their connectedness are resilient is an essential aspect of security and defense.35 Note: The 2030 agenda highlights resilience as a defining aspect of future security and defense. “NATO 2030: United for a New Era” (NATO, November 25, 2020), https://www.nato.int/nato2030/.

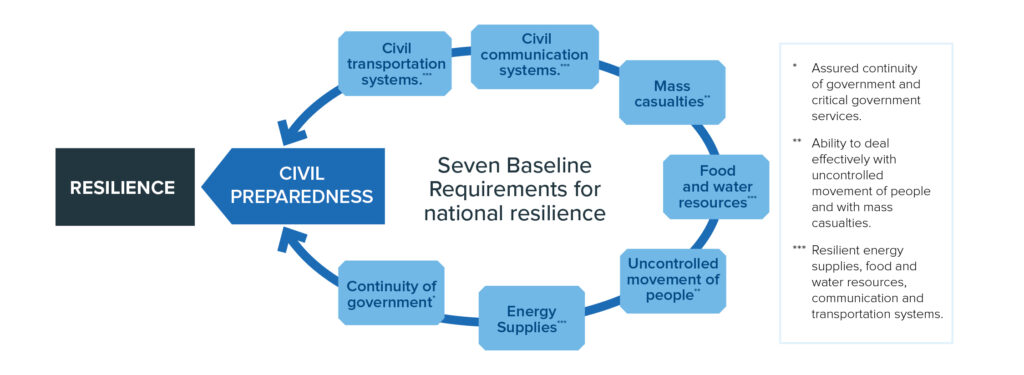

Resilience in NATO is a collective endeavor, fundamental to preventing disruptions or mitigating cascading effects across the Alliance.36 Note: Garriaud-Maylam, “Enhancing the Resilience of Allied Societies Through Civil Preparedness.” The Seven Baseline Requirements for Civil Preparedness (7BLRs37 Note: 1) Assured continuity of government and critical government services; 2) Resilient energy supplies; 3) Ability to deal effectively with the uncontrolled movement of people; 4) Resilient food and water resources; 5) Ability to deal with mass casualties; 6) Resilient communications systems; 7) Resilient transportation systems. “Resilience and Article 3.” ), introduced in 2016, answer an operationalization query, establish a method of assessment and a means for information exchange of good practices, progress made, and remaining gaps.38 Note: The 7BLRs are used to evaluate the national level of preparedness and are a subject of continuous adaptation to account for new risks and challenges. “Resilience and Article 3.” This cooperative approach to measuring and enhancing national resilience, especially in peacetime, fosters civilian and private sector readiness to support national and NATO operations in times of crisis. Continuity of government, resilient civilian infrastructure, uninterrupted essential services, and civil-military cooperation are crucial aspects of national resilience. Shortcomings in either area would reverberate across the entire system and diminish the capacity to protect. Moreover, these requirements become an essential basis for credible deterrence and defense and a critical aspect of the Alliance’s core tasks.39 Note: “Strengthened Resilience Commitment,” NATO, June 14, 2021, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_185340.htm.

Resilience should be fully integrated into NATO’s collective defense, cooperative security, and crisis management. Stability at home cannot be disconnected from stability in the broader neighborhood. Cooperation with partners in the post-Cold War period and until the Russian Federation’s illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014 centered on “projecting stability”40 Note: “Partnerships: Projecting Stability Through Cooperation,” NATO, August 25, 2021, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_84336.htm.; and “Projecting Stability in an Unstable World” (NATO Allied Command Transformation, 2017), https://www.iai.it/sites/default/files/9789284502103.pdf. through crisis management41 Note: With the necessity of a comprehensive and inclusive understanding of an operating environment, crisis management leverages the analytic potential of resilience to inform planning and tailored courses of action. and partnerships.42 Note: Jens Stoltenberg, “‘“The Three Ages of NATO: An Evolving Alliance”’ – Speech by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg at the Harvard Kennedy School,” NATO, September 28, 2016, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/opinions_135317.htm. This value-sharing and capacity-building approach to security and defense hinges upon resilience principles. It seeks to enhance preparedness and improve response to disruptions with an underlying assumption of interconnectedness. Effectively, resilience allows for understanding challenges and opportunities deriving from systemic openness and interdependence. It seeks to preserve extended cooperation and exchange while preventing these from becoming channels for disruption. 43 Note: Dr. Daniel Hamilton argues that the “arteries of […] open societies can become channels for disruption to those societies.” NATO, Enhancing Resilience across the NATO Alliance, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k-i74xBHM-U.

Developments in 2014 made it clear that NATO “must do both collective defense and manage crisis and promote stability beyond [its] borders.”44 Note: NATO, Enhancing Resilience across the NATO Alliance. In a hybrid scenario, collective defense requires more than the capacity and capability to fight. Within the changing character of war and conflict45 Note: A shift from inter (enemy-centric) to intra-state (population-centric) conflict. and expanding scope of military tasks,46 Note: To include far-reaching objectives of the rule of law, democracy, and human rights. the protection of civilians emerges as a demanding objective that requires enhanced civil-military cooperation. While not the only objective of a military operation reliant on sustained civilian support, failing to protect civilians may severely hamper the achievement of other objectives. Failure to uphold a core NATO value—the safety and security of the Alliance’s population—would significantly damage NATO’s credibility.

Resilience and the Protection of Civilians

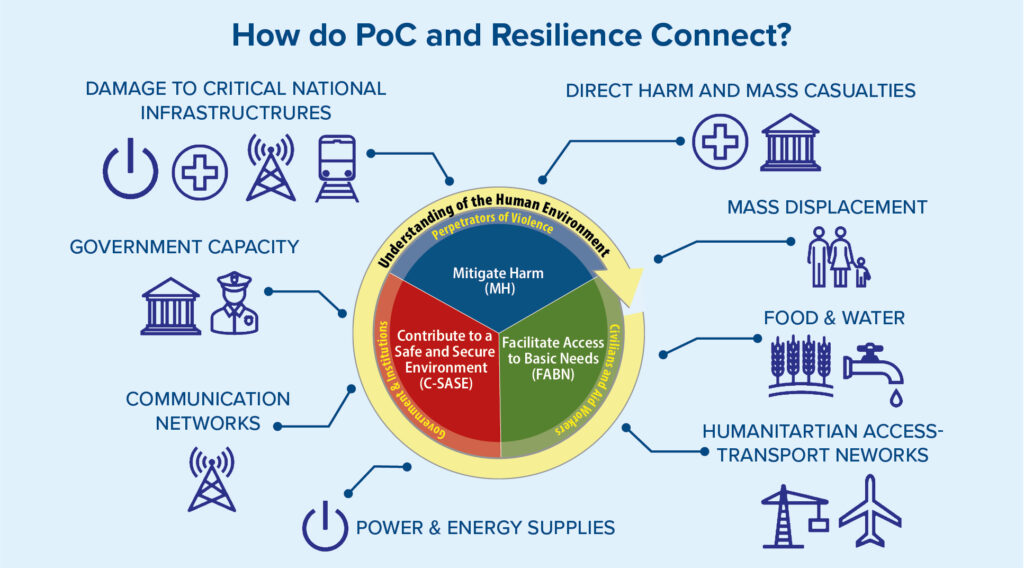

The Alliance’s policy and subsequent military framework (Figure 3) on the Protection of Civilians (PoC)47 Note: The Alliance defines the Protection of Civilians as” … all efforts taken to avoid, minimize and mitigate the negative effects that might arise from NATO and NATO-led military operations on the civilian population and, when applicable, to protect civilians from conflict-related physical violence or threats of physical violence by other actors, including through the establishment of a safe and secure environment.” “Protection of Civilians ACO Handbook” (NATO, March 11, 2021), https://shape.nato.int/resources/3/website/ACO-Protection-of-Civilians-Handbook.pdf. , adopted at the 2016 Warsaw Summit, were based on lessons learned in Afghanistan and Libya. While the connectivity between the Alliance’s PoC and Resilience policies is often mentioned in NATO circles, both are applied in isolation, with PoC taking the back seat, particularly as NATO’s focus switches to collective defense. However, the two concepts are complementary and mutually reinforcing and should be applied together, especially when addressing the challenges of urban warfare.

Cities are net importers of all essential commodities—from power, water, sanitation, food, and medical services—and are economically tuned to support their populations. They have limited capacity to respond to significant and rapid increases in population, and the same can be said for national capacities. The initial influx of Ukrainian refugees during February and March, for example, rapidly overwhelmed Moldova’s capacity to respond, with the country struggling to meet the increased demand for basic needs such as food and shelter.48 Note: The Moldavian situation is a perfect example of how national resources being overwhelmed. Madalin Necsutu, “Moldova Struggles to Cope with Wave of Ukrainian Refugees,” Balkan Insight, March 7, 2022, https://balkaninsight.com/2022/03/07/moldova-struggles-to-cope-with-wave-of-ukrainian-refugees/. Past and current conflicts have demonstrated that civilian populations will be targeted in various ways, including threats to critical infrastructure, goods, and services. Therefore, an understanding of urban resiliencies, capacities, and vulnerabilities is crucial to identifying potential adversary intentions, actions, and consequences in a future military operation. The challenge for military forces is to defeat threats embedded within the population while mitigating civilian harm as much as possible.49 Note: Dr David Killcullen and Gordon Pendleton, “Future Urban Conflict, Technology, and the Protection of Civilians: Real-World Challenges for NATO and Coalition Missions” (Stimson Center, June 10, 2021), https://www.stimson.org/2021/future-urban-conflict-technology-and-the-protection-of-civilians/. Adversaries will seek either to fix populations in place, generating significant political-military dilemmas, or force the mass movement of people to stress Alliance member states in a domino effect. These dynamics are already playing out in Ukraine and across Europe with the current exodus of Ukrainian refugees into Western Europe and the flow of refugees from Belarus across the Polish border.

Urban conflict significantly degrades essential services across all 7BLR criteria set by NATO (Figure 2). Local governance and host nations may quickly become unable to support the basic needs of the populace, leading to intense competition for limited resources, disorder, disruption, and an inability to provide a safe and secure environment. Without intervention, this will result in criminality, chaos, and humanitarian disaster.

The 7BLRs provide a valuable framework for analyzing the threats and challenges during urban conflict. However, that framework is missing the key ingredient: the civilian population. Combining PoC and resilience frameworks (Figure 3) offers a far more comprehensive appreciation of the challenges across all levels, whether strategic, operational, or tactical. Together, these combined frameworks provide a better understanding of the complex cascading effects of baseline shortfalls. They are highly suited to addressing urban conflict and evolve thinking well beyond the traditional military enablement considerations.

NATO’s PoC concept, as part of the broader Human Security approach, affords both military and civilian stakeholders a more comprehensive understanding of resilience shortfalls and their immediate and long-term impacts on societies. In more military terms, this complementary approach challenges analysts beyond the traditional PMESII (Political-Military-Economic-Social-Infrastructure-Information) top-down method, integrating it with a bottom-up one that brings a comprehensive understanding of the human environment. For example, during a recent Tabletop Exercise on urban warfare led by PAX and the Stimson Center,50 Note: For more information on the PAX – Stimson Table Top Exercise and findings in relation to both the protection of civilians and NATO National Resilience 14 June 2021, 14-Jun.-2021 al resilience, refer to Marco Grandi, Marla Keenan, and Wilbert Van Der Zeijden, “Wargame Report: Protecting Civilians in High-Intensity Urban Warfare,” Protection Series (First Germany Netherlands Corps (1GNC) Headquarters: Stimson Center, March 18, 2022), https://protectionofcivilians.org/report/wargame-report-protecting-civilians-in-high-intensity-urban-warfare/. it was evident that resilience was at least as essential to military operations as it was to protect the urban population. Both PoC and resilience have significant strategic implications, including for the Alliance’s political cohesion.

This new integrated analysis method offers multiple advantages. First, it informs prioritized political responses. Ensuring adequate resilience across all components of a modern urbanized environment is unrealistic. However, a prioritized approach allows at least minimal functionality of the most critical parts of the system to benefit the people living there and the military operating in the same environment. In identifying where to invest limited resources during peacetime, crisis, and conflict, the integrated analysis method should consider the impact on military enablement and the civilian population. Furthermore, thought should be given to resourcing programs that will reduce adverse effects on the civilian population, such as increasing energy security by developing new national energy solutions.

In addition to a state’s moral imperative to protect its citizens, this approach will also yield a strategic advantage by enhancing ties between government authorities and the people. By ensuring that resilience interventions keep civilian protection as a primary objective, populations will be more likely to accept and abide by resilience measures, which is imperative to respond to strategic shock. The COVID-19 pandemic has proven how ineffective even the best government response plans can be if the public does not abide by the state’s imposed measures. This speaks to the Clausewitz trinity: The state seeks to strengthen ties to the people by highlighting how resilience measures contribute to civilian protection, which thus reinforces trust in public institutions, both political and military.

Secondly, combining PoC into resilience considerations enhances military decision-making. Military decision-makers need to assess degraded resilience baselines’ impact on civilians within hybrid and high-intensity conflict scenarios. For example, a commander may need to defend a structure with limited military value, such as a water purification center, which could be vital to the urban population. In making these decisions, commanders will also need to consider the specific role such structures play within the overall urban system. What might seem like a negligible loss at first may prove debilitating to the system. During the Tabletop Exercise, military staff considered the value of denying internet services to an adversary occupying a Member State city to degrade the opposing force’s ability to control and leverage the local population against Alliance forces. However, cutting off Internet services would have caused significant cascading effects across all other resilience baselines, and any military advantage gained would have been outweighed by the harm caused to civilians. By considering the impact on the civilian population, particularly with the PoC lenses of mitigating harm and facilitating access to basic needs, the training audience grasped how affecting resilience baselines, particularly in an urban area, can be much more complex than it initially seems.

Finally, integrating a PoC perspective can be highly beneficial to understanding societal resilience through the military’s Understanding the Human Environment (UHE) lens51 Note: UHE is a human centric approach to understanding the operating environment from a non-combatant’s perspective. UHE addresses such factors as cultural dynamics, threats to civilians from a comprehensive human security perspective (including threats to livelihood, dignity and those deriving from natural phenomena such as floods, droughts and the like). . When the UHE lens is applied to societal resilience analysis, it can be a crucial tool in capturing internal dynamics, underlying pressures, and potential fault lines, anticipating where adversaries might act before and during hostilities to undermine societal resilience. For this reason, analysts, planners, military, and political stakeholders alike need to understand and address societal resilience vulnerabilities.

Conclusion and the Way Ahead

Combining resilience with the population-centric understanding of threats to human security, central to the PoC, offers enhanced political and military capacity to identify and address threats to the population more effectively while simultaneously preventing or mitigating harm from NATO’s actions. The synergy between Resilience and PoC is more than just theoretical; a mutually supportive relationship can have significant military-strategic, political, and humanitarian benefits.

As the growth of cities continues, so does the prospect of conflict. Critical supply lines to urban centers will be threatened, essential services denied or degraded, and societal cohesion challenged as competition for resources intensifies. Adversaries will attempt to exploit societal vulnerabilities and fault lines, undermine democratic values, and stress political systems. To counter this threat, the combined effects of resilience in concert with the protection of civilians are vital at all levels and ultimately will help protect NATO’s center of gravity: its political cohesion.

Overlaying the UHE and PMESII approaches would enable military leaders and civilians to operationalize human security through an integrated analytic Resilience-PoC approach. This would enable a comprehensive and inclusive understanding of the potential cascading effects of systemic shock across the 7BLRs. Similarly, greater attention should be paid to developing tools that would facilitate estimating a nation’s level of resilience and assist in identifying and addressing threats. A hybrid Resilience-PoC approach to analyzing urban centers in collective defense situations is essential to building a comprehensive and inclusive contextual understanding of risks and threats to the civilian population. An urban conflict makes the interconnection between resilience and PoC more apparent, illuminating the utility of applying the two concepts in unison. Increased awareness of civilian capabilities, motivations, and limitations enriches the ability to act to protect civilians, and PoC informs the prioritization of resources for enhanced resilience.

Knowing how future conflict will play out is, of course, impossible. However, an Ally’s tolerance of threats, hardship, and harm caused to its population will be an essential indicator of how it weathers a conflict. A failure to rise to the occasion may test Alliance unity. Ukraine has already shown that human rights and International Humanitarian Law violations, civilian harm, infrastructure damage, and mass migration are neither politically popular nor physically manageable. These and many other factors must be anticipated within a comprehensive approach that combines military and civil planning across the strategic-tactical continuum. Therefore, civil-military coordination, understanding resilience, and how it affects the ability to protect civilians will be critical to the political unity of the Alliance.

There is a need to go beyond a compartmentalized understanding of resilience—whether national capacities or military strength—to encompass processes, connectedness, values, principles, and leadership across multiple domains. It is critical to link resilience to other concepts that enable effective security and defense. Resilience has both a give and receive function concerning PoC. When analyzed in an integrated and complementary manner, resilience is enhanced by PoC. It can enable more effective prioritization and distribution of limited resources (including military forces). It can also provide decision-makers with a greater understanding of complex cascading effects and allow proactive approaches to mitigate societal and national resilience threats. In turn, the ability to protect civilians is significantly enhanced by strong, resilient nations and cities, which are better equipped to respond to the modern challenges of hybrid, high-intensity, and multi-domain conflict.

Notes

- 1Note: NATO’s Strategic Concept is “a key document for the Alliance. It reaffirms NATO’s values and purpose and provides a collective assessment of the security environment. It also drives NATO’s strategic adaptation and guides its future political and military development. Since the end of the Cold War, it has been updated approximately every 10 years to take account of changes to the global security environment and make sure the Alliance is prepared for the future.” “NATO 2022 – Strategic Concept,” NATO, n.d., https://www.nato.int/strategic-concept/index.html.

- 2Note: Human Security (HS) was first introduced as a term in 1994 by the UNDP Global Human Development Report. “Human Development Report 1994” (New York: United Nations Development Programme, 1994), https://www.hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/reports/255/hdr_1994_en_complete_nostats.pdf. It is broadly defined as freedom from want, fear, and indignity. In 2012, UN General Assembly adopted a standard definition. “A/RES/66/290 Follow-up to Paragraph 143 on Human Security of the 2005 World Summit Outcome,” un.org, United Nations, September 10, 2012, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N11/476/22/PDF/N1147622.pdf?OpenElement. The protection of civilians is an integral part of NATO’s human security approach. The latter approach is premised on understanding HS related to the “risks and threats to populations where NATO has operations, missions or activities” and mitigation and response measures. “Human Security,” NATO, March 11, 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_181779.htm.

- 3Note: As of 30 May 2022, the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) recorded 8,900 civilian casualties in the country: 4,074 killed and 4,826 injured. “Ukraine – Civilian Casualty Update,” United Nations, May 30, 2022, https://ukraine.un.org/sites/default/files/2022-05/Ukraine%20-%20civilian%20casualty%20update%20as%20of%2024.00%2029%20May%202022%20ENG.pdf.

- 4Note: This is one of the challenges of ‘Societal Resilience.’ As seen in the Stable State model (AJP 3.4.5), one of the five areas of a Stable State is ‘Societal Relationships.’ This is one area that is susceptible to attack that falls short of an Article 5 violation

- 5Note: “Strategic Trends Programme: Future Operating Environment 2035” (UK Ministry of Defence, December 14, 2015), https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1076877/FOE.pdf.

- 6Note: Allied Joint Publication AJP 3-10 defines the Information Environment as including three inter-related domains: Physical, Virtual and Cognitive.

- 7Note: “Urbanization,” United Nations Population Fund, accessed April 30, 2022, https://www.unfpa.org/urbanization.

- 8Note: Ukraine being a case in point with conflict unfolding in densely populated urban areas, leading to (rising) civilian deaths, displacement, and refugee flows of millions of people, alongside destruction of cities.

- 9Note: Cities are dependent on the inflow of basic needs, generate the most displacement and are the environments where most civilian harm occurs.

- 10Note: By 2050, 68.4 percent of the world’s population is expected to live in cities. “Percentage of Population at Mid-Year Residing in Urban Areas by Region, Subregion, Country and Area, 1950-2050” (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2018), https://population.un.org/wup/Download/.

- 11Note: Kiev, Mariupol (2022), Aleppo (2012–2016), Mosul (2014–2017), Grozny (1999–2000).

- 12Note: Gergana Vaklinova, “Tracing Resilience: A Context of Uncertainty, a Trajectory of Motion,” CMDR COE Proceedings 2019, 2019, 5–38.

- 13Note: For instance, ecology, engineering, psychology, and behavioral science.

- 14Note: Disruption is a cumulative term encompassing a continuum from mild stresses to significant shocks.

- 15Note: An approach to security positing a whole-of-society (armed forces, civil administrations, private sector, and the public) engagement and collaboration under the control of democratic political authorities.

- 16Note: The disaster management cycle includes preparedness, response, recovery, and reconstruction as separate yet closely interlocked phases. “Disaster and Disaster Response,” CMDR COE, n.d., https://www.cmdrcoe.org/menu.php?m_id=113.

- 17Note: Notably, Estonia, Norway (NATO members), Sweden, Finland, Switzerland (partner countries), and other nations like Singapore. For elaboration on the specificities of each country’s approach to defining and applying total defense. Joëlle Garriaud-Maylam, “Enhancing the Resilience of Allied Societies Through Civil Preparedness” (NATO Parliamentary Assembly, October 9, 2021), https://www.nato-pa.int/document/2021-enhancing-resilience-allied-societies-through-civil-preparedness-garriaud-maylam.

- 18Note: Which may be exploited to worsen tensions further and/or erode trust in and legitimacy of actions taken.

- 19Note: Applying a gender perspective allows for an intersectional analysis that investigates the needs of women, men, boys, and girls seeking differences and similarities. On NATO’s commitment to and policy, direction, and guidance on the integration of gender perspectives, see: NATO/EAPC Policy and Action Plan on the Implementation of the Women, Peace and Security Agenda: https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/pdf_2018_09/20180920_180920-WPS-Action-Plan-2018.pdf; NATO Bi-Strategic Command Directive 40-1: Integrating Gender Perspective into the NATO’s Command Structure: https://www.act.nato.int/application/files/3916/3842/6627/Bi-SCD_040-001.pdf

- 20Note: Garriaud-Maylam, “Enhancing the Resilience of Allied Societies Through Civil Preparedness.”

- 21Note: For an account of democratic resilience within NATO, see “Resolution 466: Developing a Whole-of-Society, Integrated and Coordinated Approach to Resilience for Allied Democracies” (NATO Parliamentary Assembly, October 11, 2021), https://www.nato-pa.int/download-file?filename=/sites/default/files/2021-10/2021%20-%20NATO%20PA%20Resolution%20466%20-%20Resilience_0.pdf.

- 22Note: For a discussion on democratic resilience and disinformation, consult the special report to the NATO Parliamentary Assembly. Linda Sanchez, “Bolstering the Democratic Resilience of the Alliance Against Disinformation and Propaganda” (Committee on Democracy and Security (CDS): NATO Parliamentary Assembly, October 10, 2021), https://www.nato-pa.int/download-file?filename=/sites/default/files/2021-10/013%20CDS%2021%20E%20rev.%202%20fin%20-%20DEMOCRATIC%20RESILIENCE%20-%20SANCHEZ.pdf.

- 23Note: “Brussels Summit Communiqué Issued by the Heads of State and Government Participating in the Meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Brussels,” NATO, June 14, 2021, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_185000.htm.

- 24Note: “The North Atlantic Treaty” (NATO, April 4, 1949), https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_17120.htm.

- 25Note: “The capacity of each member nation to “resist and recover from a major shock such as a natural disaster, failure of critical infrastructure, or a hybrid or armed attack.” “Resilience and Article 3,” NATO, June 11, 2021, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_132722.htm.

- 26Note: Rear Admiral John W. Tammen, “NATO’s Warfighting Capstone Concept: Anticipating the Changing Character of War,” NATO Review, July 9, 2021, https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2021/07/09/natos-warfighting-capstone-concept-anticipating-the-changing-character-of-war/index.html.

- 27Note: NWCC offers a threat-informed vision of challenges and details how NATO Allies must develop their militaries to maintain advantage for the next twenty years. Tammen, “NATO Review – NATO’s Warfighting Capstone Concept.”

- 28Note: Military resilience, military-civil resilience, and civilian resilience. “The NATO Warfighting Capstone Concept: Key Insights from the Global Expert Symposium Summer 2020” (Global Expert Symposium, The Hague: The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, 2020), 12, https://hcss.nl/wp-content/uploads/attachments/NATO_Symposium_Final_Version_For_Publication.pdf.

- 29Note: Civil-military cooperation is essential for resilience as it allows for trust to evolve from a mutual understanding of requirements and capabilities.

- 30Note: Davis Ellison, “Mastering the Fundamentals: Developing the Alliance for the Future Battlefield,” The Three Swords, October 2021, https://jwc.nato.int/download_file/view/1643/277.

- 31Note: Society is a system of individuals, civil structures, resources, services, and relations.

- 32Note: Wolf-Diether Roepke and Hasit Thankey, “Resilience: The First Line of Defence” (Defence Policy and Planning Division – NATO Headquarters, February 2019), https://www.jwc.nato.int/images/stories/_news_items_/2019/three-swords/ResilienceTotalDef.pdf.

- 33Note: NATO, How Does NATO Support Allies’ Resilience and Preparedness?, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zV-lGVupAv4.

- 34Note: That heavily rely on external supplies of goods and services.

- 35Note: The 2030 agenda highlights resilience as a defining aspect of future security and defense. “NATO 2030: United for a New Era” (NATO, November 25, 2020), https://www.nato.int/nato2030/.

- 36Note: Garriaud-Maylam, “Enhancing the Resilience of Allied Societies Through Civil Preparedness.”

- 37Note: 1) Assured continuity of government and critical government services; 2) Resilient energy supplies; 3) Ability to deal effectively with the uncontrolled movement of people; 4) Resilient food and water resources; 5) Ability to deal with mass casualties; 6) Resilient communications systems; 7) Resilient transportation systems. “Resilience and Article 3.”

- 38Note: The 7BLRs are used to evaluate the national level of preparedness and are a subject of continuous adaptation to account for new risks and challenges. “Resilience and Article 3.”

- 39Note: “Strengthened Resilience Commitment,” NATO, June 14, 2021, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_185340.htm.

- 40Note: “Partnerships: Projecting Stability Through Cooperation,” NATO, August 25, 2021, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_84336.htm.; and “Projecting Stability in an Unstable World” (NATO Allied Command Transformation, 2017), https://www.iai.it/sites/default/files/9789284502103.pdf.

- 41Note: With the necessity of a comprehensive and inclusive understanding of an operating environment, crisis management leverages the analytic potential of resilience to inform planning and tailored courses of action.

- 42Note: Jens Stoltenberg, “‘“The Three Ages of NATO: An Evolving Alliance”’ – Speech by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg at the Harvard Kennedy School,” NATO, September 28, 2016, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/opinions_135317.htm.

- 43Note: Dr. Daniel Hamilton argues that the “arteries of […] open societies can become channels for disruption to those societies.” NATO, Enhancing Resilience across the NATO Alliance, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k-i74xBHM-U.

- 44Note: NATO, Enhancing Resilience across the NATO Alliance.

- 45Note: A shift from inter (enemy-centric) to intra-state (population-centric) conflict.

- 46Note: To include far-reaching objectives of the rule of law, democracy, and human rights.

- 47Note: The Alliance defines the Protection of Civilians as” … all efforts taken to avoid, minimize and mitigate the negative effects that might arise from NATO and NATO-led military operations on the civilian population and, when applicable, to protect civilians from conflict-related physical violence or threats of physical violence by other actors, including through the establishment of a safe and secure environment.” “Protection of Civilians ACO Handbook” (NATO, March 11, 2021), https://shape.nato.int/resources/3/website/ACO-Protection-of-Civilians-Handbook.pdf.

- 48Note: The Moldavian situation is a perfect example of how national resources being overwhelmed. Madalin Necsutu, “Moldova Struggles to Cope with Wave of Ukrainian Refugees,” Balkan Insight, March 7, 2022, https://balkaninsight.com/2022/03/07/moldova-struggles-to-cope-with-wave-of-ukrainian-refugees/.

- 49Note: Dr David Killcullen and Gordon Pendleton, “Future Urban Conflict, Technology, and the Protection of Civilians: Real-World Challenges for NATO and Coalition Missions” (Stimson Center, June 10, 2021), https://www.stimson.org/2021/future-urban-conflict-technology-and-the-protection-of-civilians/.

- 50Note: For more information on the PAX – Stimson Table Top Exercise and findings in relation to both the protection of civilians and NATO National Resilience 14 June 2021, 14-Jun.-2021 al resilience, refer to Marco Grandi, Marla Keenan, and Wilbert Van Der Zeijden, “Wargame Report: Protecting Civilians in High-Intensity Urban Warfare,” Protection Series (First Germany Netherlands Corps (1GNC) Headquarters: Stimson Center, March 18, 2022), https://protectionofcivilians.org/report/wargame-report-protecting-civilians-in-high-intensity-urban-warfare/.

- 51Note: UHE is a human centric approach to understanding the operating environment from a non-combatant’s perspective. UHE addresses such factors as cultural dynamics, threats to civilians from a comprehensive human security perspective (including threats to livelihood, dignity and those deriving from natural phenomena such as floods, droughts and the like).