By William Reinsch

Editor’s Note: This is the second in a series of three pieces examining demographic trends and their impact on the global economy.

Last week I wrote about demography and the opportunity worker-deficient nations have to put themselves back on the path to growth by taking in young workers from countries that have a surplus. I had no illusions that anyone would follow my advice, and so far there is no evidence anyone has. There is, however, another aspect to demographic reality that deserves some comment, and that is how a changing population inside a country changes its politics and policy.

The United States right now is a good laboratory for that. My generation, the Baby Boomers, the largest in our history, is beginning to fade from the scene. As one of the first Boomers, I’m not planning on fading anytime soon, but there is an inevitability in the passage of time that we all have to acknowledge. What people are beginning to realize is the current impact a generation of this size has on our economy and our politics. Sixty years ago the problem was building enough schools to hold all of us. Then it was finding enough jobs to keep everyone employed. Now it is finding enough money for retirement and to pay ever-increasing health care costs. I suspect columnists will soon be writing about the cemetery shortage and the advantages of cremation.

Since we are many and we vote, my generation has been able to influence the public policy debate into addressing things we care about, which right now are health care, taxes, retirement benefits and, for some, the high cost of educating our children and grandchildren. And, like every generation before us, except perhaps the one immediately before us, we have voted for what is good for us without much thought as to whether it’s good for everybody.

It now appears that is changing. The Millennials have not only gained on us; they have taken over. According to the Census Bureau last April there are now more Millennials (75.9 million) than Boomers (74.9 million), and Gen Xers, the smaller generation between the other two, will pass us by 2028. Post-Millennials (somebody will come up with a better name eventually) — those born between 1998 and 2014 — will be even more than the Millennials, though not as many as us Boomers.

With the change in population inevitably comes change in policy. Our elections will increasingly be about what the Millennials want, assuming they actually begin to vote, which is an open question at this point. There has been a lot written about what they are like and what they want, not all of it flattering (though I am very proud of both my GenX son and my Millennial son), but since this column is usually about trade and international economic policy, let’s focus on that, and there they appear to be a remarkably fearless and outward looking group. Looking at the Brexit vote in the U.K., for example, people under 35 opposed leaving the EU by 65% to 35%. It was my generation, the pensioners, who favored it 60% to 40%. That’s ironic since much of the debate was about immigrants coming in and stealing jobs; yet the group that had the most to lose if that happened was strongly supportive.

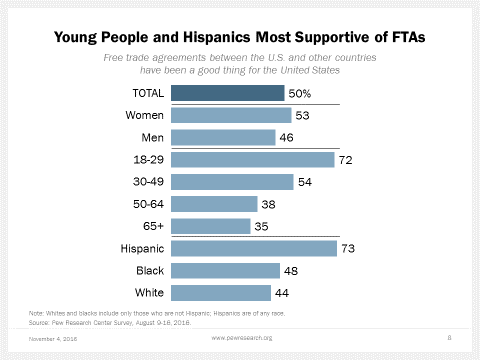

In the U.S., we see the same thing, as the following chart, courtesy of Bruce Stokes and the Pew Research Center, shows.

If you think about it, this makes sense. The young have always been the adventurous, the seekers of new opportunities and experiences. One of my favorite cartoons is that of the long-haired, bearded young hitchhiker standing at the side of the road with a sign that says only, “Further.” Our Millennials have grown up in a global world, have been exposed to foreign cultures through travel and friends from other countries, immigrants, relatives, and visitors, and instinctively understand that our future is out there in Tom Petty’s “great wide open.” In that sense, they’re not really that different from the way we were when we were their age. In political terms, though, the important thing is that there are a lot of them; they will soon be setting our national course; and that course will be an internationalist one that sees trade as an opportunity rather than a threat. It may not mean their father’s or grandfather’s trade policy since they also seem to be concerned about poverty and inequality and are suspicious of large companies, but their direction will be outward rather than inward.

So, policy makers be prepared — trade is not going away and will not be a four letter word much longer. All I have to do is get my kids to vote.

Next time, in what NPR’s Car Guys refer to as the third half of the show, we will discuss the implications of generational change for our political parties.

__

William Reinsch is a Distinguished Fellow with the Stimson Center, where he works principally with the Center’s Trade21 initiative.

Photo credit: ITU Pictures via Flickr

Into the Great Wide Open: How Millennials Look at Trade

By William Reinsch

In Trade & Technology

By William Reinsch

Editor’s Note: This is the second in a series of three pieces examining demographic trends and their impact on the global economy.

Last week I wrote about demography and the opportunity worker-deficient nations have to put themselves back on the path to growth by taking in young workers from countries that have a surplus. I had no illusions that anyone would follow my advice, and so far there is no evidence anyone has. There is, however, another aspect to demographic reality that deserves some comment, and that is how a changing population inside a country changes its politics and policy.

The United States right now is a good laboratory for that. My generation, the Baby Boomers, the largest in our history, is beginning to fade from the scene. As one of the first Boomers, I’m not planning on fading anytime soon, but there is an inevitability in the passage of time that we all have to acknowledge. What people are beginning to realize is the current impact a generation of this size has on our economy and our politics. Sixty years ago the problem was building enough schools to hold all of us. Then it was finding enough jobs to keep everyone employed. Now it is finding enough money for retirement and to pay ever-increasing health care costs. I suspect columnists will soon be writing about the cemetery shortage and the advantages of cremation.

Since we are many and we vote, my generation has been able to influence the public policy debate into addressing things we care about, which right now are health care, taxes, retirement benefits and, for some, the high cost of educating our children and grandchildren. And, like every generation before us, except perhaps the one immediately before us, we have voted for what is good for us without much thought as to whether it’s good for everybody.

It now appears that is changing. The Millennials have not only gained on us; they have taken over. According to the Census Bureau last April there are now more Millennials (75.9 million) than Boomers (74.9 million), and Gen Xers, the smaller generation between the other two, will pass us by 2028. Post-Millennials (somebody will come up with a better name eventually) — those born between 1998 and 2014 — will be even more than the Millennials, though not as many as us Boomers.

With the change in population inevitably comes change in policy. Our elections will increasingly be about what the Millennials want, assuming they actually begin to vote, which is an open question at this point. There has been a lot written about what they are like and what they want, not all of it flattering (though I am very proud of both my GenX son and my Millennial son), but since this column is usually about trade and international economic policy, let’s focus on that, and there they appear to be a remarkably fearless and outward looking group. Looking at the Brexit vote in the U.K., for example, people under 35 opposed leaving the EU by 65% to 35%. It was my generation, the pensioners, who favored it 60% to 40%. That’s ironic since much of the debate was about immigrants coming in and stealing jobs; yet the group that had the most to lose if that happened was strongly supportive.

In the U.S., we see the same thing, as the following chart, courtesy of Bruce Stokes and the Pew Research Center, shows.

If you think about it, this makes sense. The young have always been the adventurous, the seekers of new opportunities and experiences. One of my favorite cartoons is that of the long-haired, bearded young hitchhiker standing at the side of the road with a sign that says only, “Further.” Our Millennials have grown up in a global world, have been exposed to foreign cultures through travel and friends from other countries, immigrants, relatives, and visitors, and instinctively understand that our future is out there in Tom Petty’s “great wide open.” In that sense, they’re not really that different from the way we were when we were their age. In political terms, though, the important thing is that there are a lot of them; they will soon be setting our national course; and that course will be an internationalist one that sees trade as an opportunity rather than a threat. It may not mean their father’s or grandfather’s trade policy since they also seem to be concerned about poverty and inequality and are suspicious of large companies, but their direction will be outward rather than inward.

So, policy makers be prepared — trade is not going away and will not be a four letter word much longer. All I have to do is get my kids to vote.

Next time, in what NPR’s Car Guys refer to as the third half of the show, we will discuss the implications of generational change for our political parties.

__

William Reinsch is a Distinguished Fellow with the Stimson Center, where he works principally with the Center’s Trade21 initiative.

Photo credit: ITU Pictures via Flickr