About this Series

This paper is part of Stimson’s Civil-Military Relations in Myanmar series, which seeks to analyze the complex relationship between the civilian and military sides of the Burmese government and the implications for the country’s future peace and development. Since the founding of the country, the Burmese military, or Tatmadaw, has held a unique and privileged status across institutions of power. And despite movement toward democracy in the past decade, the relationship between the civilian and military sides remains deeply unsettled. This contest for power and the political, security, and constitutional crises it creates have had far-reaching effects on Myanmar’s political processes, its ongoing civil war, the Rohingya crisis, and regional peace and stability—a reality most recently and poignantly seen in the 2021 coup d’état staged by the Tatmadaw against the civilian government. The series brings together the expertise of leading experts on Myanmar, Southeast Asia, democratization, and policy to uncover the complex dynamics between the two sides. The series provides key insights and recommendations for disentangling the contentious relationship and charting a path forward for relevant stakeholders in Myanmar.

Introduction

Since the end of the Second World War, no other country in Asia nor worldwide has been governed by soldiers as long as Myanmar. Military rule came in two forms: direct and institutional (1962–1974 and 1988–2010) and in the form of quasi-civilian government, in which military-leaders-turned-civilians occupied supreme positions (1974–1988 and 2010–2015). It would be naïve to assume that after more than half a century of military dominance over society, the state, and the economy, the Tatmadaw would simply “return to the barracks” and focus exclusively on an apolitical national defense mission. Indeed, with the generally free and fair multiparty elections of 2015, the country moved further away from military rule and toward what some call a “ ‘quasi-democratic’ administration—a uniquely Burmese government tenuously balancing an amalgam of military, civilian and diverse ethnic minority interests.”1David Steinberg, “Myanmar elections another step towards democracy?,” East Asia Forum, October 25, 2020, https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2020/10/25/myanmar-elections-another-step-towards-democracy/. However, this regime hybrid turned out to be unsustainable in a civil-military environment characterized by mutual distrust and brinkmanship.

Scholars of regime transitions agree that democratization in a country is not just about electing a new government through free, fair, and competitive elections but entails a much more comprehensive political overhaul. In particular, new political leaders must enjoy sufficient effective power to govern. Transforming authoritarian civil-military relations is therefore a key component of any regime transitions from autocratic to democratic government. However, military rulers are often the ones to set the conditions for a transition to civilian government from a position of strength. It is therefore not a surprise that many military leaders were able to exercise substantial control over the process and outcomes of the transition, which often enabled the armed forces to preserve acquired prerogatives.

Yet what was exceptional about the case of Myanmar was the immense depth of military control over state, politics, economy, and society before, during, and after the transition from military to civilian government. This raises the following questions: When are post-praetorian governments able to reform their civil-military relations so that the military supports civilian governance? What are lessons to be learned for Myanmar?

With these questions in mind, this paper reviews the relevant literature on the transformation of civil-military relations in transitions from military rule to civilian government since the last quarter of the twentieth century. Of course, the case of Myanmar exhibits many important differences compared with countries in Latin America, Sub-Sahara Africa, or even inside the Asia-Pacific region. Keeping such limitations in mind, I will focus primarily on Southeast Asian countries concerning the praetorian legacies and how such legacies affected the role of militaries in the transition from military government to civilian government.

Transitions from Military Rule Toward Something Else: Key Concepts

In the past five decades or so, the world has seen numerous transitions from authoritarian rule toward something else. Not all of these transitions resulted in the instauration of a stable, functioning, and legitimate democracy. Often, regime transitions restored new autocracies. Given the ambiguous character of regime transition in Myanmar, it is important to first clarify a number of concepts that are key to the empirical analysis.

First, the distinction between democracy and autocracy “deals with the question of regime type.”2Robert M. Fishman, “Rethinking State and Regime: Southern Europe’s Transition,” World Politics 42 (1990): 422–440; here 428. A political regime “designates the institutionalized set of fundamental formal and informal rules identifying the political power holders [and] regulates the appointments to the main political posts […] as well as the […] limitations on the exercise of political power.”3Svend E. Skaaning, “Political Regimes and Their Changes: A Conceptual Framework,” Working Paper 55 (2006): 1–29, https://cddrl.fsi.stanford.edu/publications/political_regimes_and_their_changes_a_conceptual_framework, here 15. In contrast, a government is understood as those key political institutions and authorities with a monopolized right to formalized political decision-making. Governments are usually far less durable than regimes.

Second, it is important to develop a clear understanding of what democracy is or is not. For the purpose of this paper, it is sufficient to acknowledge that despite the nature of democracy as an “essentially contested concept,” 4David Collier, Fernando Daniel Hidalgo, and Andra Olivia Maciuceanu, “Essentially Contested Concepts: Debates and Applications,” Journal of Political Ideologies 11, no. 3 (2006), https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13569310600923782. actual empirical research on democratization relies on a procedural understanding of democracy. In this regard, the nature of civil-military relations is relevant, because in a democracy, the “effective power to govern” must rest with democratically elected representatives rather than political actors that are not subject to the democratic process. Only if the armed forces are subordinate to the authority of democratically legitimated civilian governments and do not exert undue political influence on political decisions can democratic procedures function effectively.5Robert Dahl, Democracy and Its Critics (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1989), 250.

Third, the term military rule (synonymously: military-led regimes) denotes all variants of non-democratic (synonymously: autocratic) political regimes governed by a single active-duty or retired military officer, or a group of members of the national armed forces. Military rule can take different forms: direct or indirect (quasi-military) rule, or rule by collegial bodies representing the officer corps. In the latter case, multiple officers influence decision-making, representing the military institution and government controlled by a single officer absent of elite constraints, which is often called “military strongman” rule.6Paul Brooker, Non-Democratic Regimes, 2d ed. (Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009); Barbara Geddes, Joseph Wright, and Erica Frantz, How Dictatorships Work. Power, Personalization, and Collapse (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 2018); Barbara Geddes, Joseph Wright, and Erica Frantz, “Military Rule,” Annual Review of Political Science 17 (2014): 147-162. Such differences are important but demarcate various subtypes of military rule, not categorical differences such as between military rule, party rule, autocratic monarchies, or personalist regimes.

Fourth, when analyzing transitions from authoritarian rule to a political democracy, it is important to keep in mind that such processes involve actually two transitions.7Guillermo A. O’Donnell, “Transitions, Continuities, and Paradoxes,” in Issues in Democratic Consolidation: The New South American Democracies in Comparative Perspective, ed. Scott Mainwaring, 17-56 (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1992). The first transition, if successful, is one from autocratic government to the installation of a democratic government. Once a transition from autocratic rule in a given country has reached this point, a second transition can begin. This second one is from democratic government toward the effective functioning of a democratic regime.8O’Donnell, “Transitions, Continuities,” 18. During the first transition, the “military challenge” for civilian actors is to figure out how to achieve the inauguration of a democratic government without provoking military resistance. The challenge for a democratic government during the second transition is to establish functional institutions of civilian control over the military.9Adam Przeworski, “Democracy and the Market: Political and Economic Reforms in Eastern Europe and Latin America,” in The Democracy Sourcebook, eds. Robert A. Dahl, Ian Shapiro, and José A. Cheibub, 76-92 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003), 81-85. These challenges are especially acute and arduous in countries with a strong legacy of “praetorianism” and where the military is able to secure political and institutional privileges for itself during the transition to democracy. Evidently, the military coup d’état of February 1, 2021, demonstrates that the National League of Democracy (NLD)-led government failed to succeed in managing this challenge.

Fifth, the issue of civilian control over the military is traditionally at the center of civil-military reforms in transitions from military rule toward something else. There is no agreement among scholars on what exactly civilian control over the military entails, or how researchers should measure it. However, in recent years, scholars have advanced conceptions that share two fundamental assumptions. First, civilian control is about the political power of non-military political actors relative to the military. Second, and related, political-military relations can be best understood as a continuum ranging from full civilian control to complete military dominance over the political system. Therefore, civilian control over the military is a gradual phenomenon. In our previous work, my colleague and I defined “civilian control” as a particular state in the distribution of political authority in which civilian political leaders (either democratically elected or autocratically selected) have the full authority to decide on national policies and their implementation across five political decision-making areas: elite recruitment, public policy, internal security, national defense, and military organization.10Aurel Croissant, David Kuehn, Philip Lorenz, and Paul W. Chambers, Democratization and Civilian Control in Asia (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013). By evaluating who has the power to make decisions in each of these areas, one can make a comprehensive assessment of civil-military relations in new democracies. Full-fledged civilian control requires that civilian authorities enjoy uncontested decision-making power in all five areas, while in the ideal-type military regime, soldiers rule over all five areas. Military challenges to civilian decision-making power can take two analytically distinct forms. The first one, institutionalized prerogatives, describes formal rights by which the military is able “to structure relationships between the state and political or social society.”11Alfred Stepan, Rethinking Military Politics: Brazil and the Southern Cone (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988), 93. The second form, contestation, encompasses informal behavior by which the military challenges civilian decision-making power. The more institutional prerogatives a military holds, the less it has to rely on contestation. However, in the absence of institutionalized prerogatives, contestation can be an effective strategy for the military to enforce its political, economic, and organizational interests.

Transitions from Military Rule Toward Something Else: Key Assumptions

There is little agreement among researchers on what explains the specific type or form of military reforms during situations of regime change and democratic transitions. However, five theoretical assumptions or generalizations seem well tested and established.

First, civil-military relations are the outcome of a combination of structural and agential factors. The difference between various scholarly explanations is the relative importance these theories attach to “structure” and “agency” in constructing their explanations.12David Kuehn, “Theoretical Landscape,” in Civil-Military Relations: Control and Effectiveness Across Regimes, eds. Thomas C. Bruneau and Aurel Croissant, 19-34 (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2019).

Second, civil-military relations are largely a path-dependent phenomenon. Path dependence allows institutions to freeze the initial conditions at the moment when the institution was established. Contemporary civil-military relations thus usually derive from the initial conditions of the formation of state, nation, and polity.13Muthiah Alagappa, “Introduction,” in Coercion and Governance: The Declining Political Role of the Military in Asia, ed. Muthiah Alagappa, 1-28 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001); Mark Beeson and Alex J. Bellamy, Securing Southeast Asia: The Politics of Security Sector Reform (London: Routledge, 2008). In the formative period of regime- and state-building, a certain constellation of civilian and military actors molded the institutional civil-military framework in line with their interests and according to the balance of power at that time. Because the existing institutions define power relations and hierarchies, empowering some actors while closing channels of power to others, and are likely to have developed some degree of legitimacy or acceptance, they are difficult to change once they are established.

Third, and related to this, historical legacies of politically empowered military establishments and commonplace military interventions into politics as well as the legacies of the first transition from authoritarian rule to a democratic government have a strong influence over the course of post-authoritarian civil-military relations. Of course, authoritarian legacies and the conditions created by transitions negotiated with the previous regime are reversible. However, the deeper the traditions of “military praetorianism” and the stronger the military’s sway over the first transition, the better are military leaders able to gain or maintain guarantees for military autonomy and privileges. These deals are more difficult to be revised by civilian political leaders, since military leaders had permitted the development of military-backed patronage parties, which, in turn, increases the likelihood that allies of the military have significant representation in democratically elected bodies such as constituent assemblies, state legislatures, or the presidency.14Abel Escribá-Folch, “Authoritarian Responses to Foreign Pressure: Spending, Repression, and Sanctions,” Comparative Political Studies 45, no. 6 (2012): 683-713.

Fourth, reforms in civil-military relations essentially have an endogenous character. External support or developments elsewhere may be an important ingredient for the implementation of such reforms. Multilateral military cooperation and bilateral assistance, foreign powers’ policy signals, membership in international organizations, or leverage of mature democracies can raise the costs of military interventions into politics, may confront domestic military elites with new role models and opportunities for professional socialization, and can provide civilian elites with resources needed to create civil-military reform coalitions.15Zoltan Barany, The Soldier and the Changing State: Building Democratic Armies in Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Americas (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012); Timothy M. Edmunds, “Security Sector Reform,” in Routledge Handbook of Civil-Military Relations, eds. Thomas C. Bruneau and Florina Cristiana Matei, 48-60 (London: Routledge, 2012). Still, the engines of change in civil-military relations are internal primarily, and external factors cannot replace the domestic forces that have to conceive or execute reform. To create stable conditions for further developments, military reforms must have an endogenous character.16Narcís Serra, The Military Transition: Democratic Reform of the Armed Forces (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 241.

Fifth and final, the most likely reform path is one of gradualism. Military bureaucracies are resistant to change. They prefer the status quo and if they do have to change, military bureaucracies favor incremental reform because it minimizes disruption and provides opportunities for them to influence the process during the implementation period. Moreover, militaries are not just bureaucracies; they are also political organizations with a stake in preserving their quota of power.17David Pion-Berlin, “Foreword,” in Who Guards the Guardians and How: Democratic Civil-Military Relations, eds. Thomas C. Bruneau and Scott D. Tollefson, iii-xiv (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006). In many countries transitioning from dictatorship to democracy, this quota is sizeable; militaries have, throughout the years, accrued decision-making autonomy, generous budgets, numerous perks and privileges, and even immunity from prosecution. These are advantages they would rather not give up and thus they attempt to fend off efforts by civilians to rein them in. Moreover, change is also threatening to those inside the organization who are accustomed to organizational power, perks, and privileges. Those in positions of authority must often be convinced that a change is a win-win situation—that it will mean the creation of a more effective fighting force without a loss of resources, workforce, or positions. For these reasons, agents of change usually come from the outside, 18Eliot Cohen, “Change and Transformation in Military Affairs,” Journal of Strategic Studies 27, no. 3 (2004): 395-407. but civilian change agents must be on good terms with military commanders who then are more likely to be receptive to their ideas and who can use their authority to set the innovations in motion down through the chain of command.19Pion-Berlin, “Foreword.”

Political Transitions and the Transformation of Civil-Military Relations: Global Perspective

Transitions from military rule are not an empirically rare phenomenon. A global study by Kuehn and Croissant in 2020 found that 29 of 71 transitions from authoritarian rule to democracy in the period 1974–2010 were transitions from military to democratic rule. In 26 of these 29 transitions, the armed forces exercised some (14) or a dominant influence (12) over the transition process. In Asia-Pacific, six out of 11 transitions began in military-controlled autocracies (Thailand is counted twice: 1992 and 2007). The military had some or much influence over the course of the transition in seven cases: the Philippines (1986–1987), Thailand (1992 and 2007), Indonesia (1998–1999), South Korea (1987–1988), Bangladesh (1990), and Pakistan (1988).

Most transitions from military rule took place by means of planned elections of the outgoing regime. Often, the military leaders reacted to mass protest and opposition from below by either defecting from the authoritarian government or pressuring reluctant leaders to initiate a transition. This has been the case, for instance, in Bangladesh, South Korea, Indonesia, and Thailand (1992). Only in very few cases, i.e., Greece (1974) and Argentina (1982) was the military forced to relinquish power as a result of disastrous military adventures that eroded support by the military-as-institution for the military-as-government.20Felipe Agüero, “Legacies of Transitions: Institutionalization, the Military, and Democracy in South America,” Mershon International Studies Review 42 (1998): 383-404; Juan J. Linz and Alfred Stepan, eds., Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation: Southern Europe, South America, and Post-communist Europe (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996). Not a single transition was the result of an armed insurrection against a military government.21David Kuehn and Aurel Croissant, “Civilian Control and Democratization in the Third Wave: Routes to Reform,” unpublished manuscript, 2020.

Wherever the military was able to initiate the regime transition from a position of relative strength, soldiers were able to determine the conditions for relinquishing power themselves. Under such conditions, the short-term outcome of the reform process was usually the instauration of a democratic government with limited, little, or no control over the armed forces, whereas the military successfully carved out political niches within the new political orders. As a result, most post-military governments and regimes had to cope with the issue of praetorian legacies. Reserved domains and military prerogatives often included22Kuehn and Croissant, “Civilian Control.”

- a national security council dominated by representatives of the military (Brazil, Turkey);

- reserved seats for representatives of the military in the lower and/or upper house of parliament (Chile, Indonesia);

- economic concessions, including budgetary autonomy and/or military control over vast business complexes (most of Central and South America, Pakistan, Indonesia, Thailand);

- military autonomy in its internal affairs (almost everywhere); and

- military control over national defense policy and/or matters of internal security (again, almost all countries).

Why would democratic governments consent to military tutelage that restricts the possible range of democratic outcomes, and introduce a source of instability into the new political order? One obvious answer is that civilians simply lacked the power and resources that would have been necessary to block the military from pushing through with its demands. A second one is that moderate civilian reformists may have feared that any attempt to impose stronger limits on military autonomy would have immediately provoked exactly what it was intended to eliminate—military intervention. A third answer is that in many countries with a long tradition of praetorianism, the institutional models through which civilians could have controlled the military were absent at the time of the transition from military to civilian government. Without such an apparatus of civilian control, the choice faced by civilian governments may have been one of either tolerating military autonomy, reserved domains, and tutelary power or destroying the military altogether.

Southeast Asian Perspective: Indonesia and Thailand as Reference Points

Whatever the reasons, whenever the military was able to secure political and/or institutional privileges for itself during the first transition, it delayed the institutionalization of democratic reforms in civil-military relations during the second transition from democratic government to a consolidated democratic regime. This is clearly evidenced by the cases of Thailand and Indonesia, two Southeast Asian countries that have attempted—with varying success—political transitions out of military-led authoritarianism in recent decades. Indonesia and Thailand, together with Myanmar, are cases par excellence of praetorian civil-military relations in Southeast Asia. Therefore, the experiences of these two countries with praetorian legacies, military roles during the transition, and civil-military reforms during the process of regime transition provide relevant reference points for Myanmar.

Indonesia: Successes and Shortcomings of Civil-Military Reforms

Indonesia’s authoritarian regime of President Suharto (1967–1998) was originally a military regime. In the early years of the so-called New Order, the Tentera Nasional Indonesia (TNI; called Angkatan Bersenjata Republik Indonesia or ABRI from 1962 to 1999) was the predominant political force within the government, second only to the president himself.23Dan Slater, Ordering Power: Contentious Politics and Authoritarian Leviathans in Southeast Asia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010); John Gledhill, “Competing for Change: Regime Transition, Intrastate Competition, and Violence,” Security Studies 21 (2012): 43-82. This was reflected, first of all, in the further entrenchment of the so-called territorial structure, which “facilitated the New Order’s grip on the provinces, as Suharto also used the territorial system to ensure the army could exert direct pressure on rural voters.”24Gregory Vincent Raymond, “Naval Modernization in Southeast Asia: Under the Shadow of Army Dominance?” Contemporary Southeast Asia 39 (2017): 149-177; here 162. Furthermore, under the dwifungsi doctrine, the military became entwined with political institutions, most evident in its dominant position in the regime’s main sociopolitical organization, Golkar, its reserved seats in national and subnational parliaments, and the occupation of many civilian administrative positions, minister posts, and governorships by active soldiers.25Sukardi Rinakit, The Indonesian Military after the New Order (Singapore: NIAS Press, 2005). In addition, the Indonesian military expanded and deepened its economic and commercial roles, leading observers to consider this the third role in an expanded “trifungsi.”26Lesley McCulloch, “Trifungsi: The Role of the Indonesian Military in Business,” in The Military as an Economic Actor: Soldiers in Business, eds. Jörn Brömmelhörster and Wolf-Christian Paes, 94-123 (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2003).

Beginning in the 1980s, however, Suharto’s New Order experienced a double transformation of personalization and substantial “civilianization,” limiting the autonomous role of the military, but also creating to some extent a separation between the armed forces and the regime. In addition, Suharto began to sponsor civilian politicians, effectively civilianizing the regime party. Finally, Suharto’s misuse of the military promotion system and patronage politics generated internal divisions and, by the mid-1990s, the military was deeply factionalized into “losers” and “winners” of Suharto’s “franchise system.”27Ross McLeod, “Inadequate Budgets and Salaries as Instruments for Institutionalizing Public Sector Corruption in Indonesia,” South East Asia Research 16 (2008): 199-223; here 200; Terence Lee, Defect or Defend: Military Responses to Popular Protests in Authoritarian Asia (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015). Consequently, “what started as a system of oligarchic military rule evolved into a highly personalized regime, backed in nearly equal measure by military and civilian organizations.”28Dan Slater, “Altering Authoritarianism: Institutional Complexity and Autocratic Agency in Indonesia,” in Explaining Institutional Change: Ambiguity, Agency, and Power, eds. James Mahoney and Kathleen Thelen, 132-167 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 133.

When the Suharto regime crumbled in May 1998, the defection of senior military commanders from the dictator was key to his downfall. Even though military officers made their preferences heard in the negotiations that led to free and fair elections and the inauguration of a new, democratic government in 1999, the transition was managed by civilian elites in regime and opposition.29Marcus Mietzner, Military Politics, Islam, and the State in Indonesia: From Turbulent Transition to Democratic Consolidation (Singapore: ISEAS, 2009). Since 1999, the democratic reform process (reformasi) has profoundly changed the socio-political roles of the TNI. The military and the police (POLRI) were institutionally separated. The TNI gave up its dwifungsi doctrine and cut its ties with Golkar. Active-duty officers had to leave most posts in the civilian administration, and TNI/POLRI lost their reserved seats in national and subnational legislatures. Finally, the military had to allow for its “foundations” (yayasan), managing some of its property and investments, to be audited.30Philip Lorenz, “Principals, Partners and Pawns: Indonesian Civil Society Organizations and Civilian Control of the Military” (PhD diss., University of Heidelberg, 2015).

Despite these reforms, the legacies of the (pre–)New Order era have not been fully overcome. For example, the TNI still maintains unaccountable commercial activities and has successfully blocked any political attempt to abolish the army’s territorial structure and to redirect its role to external defense. Instead, the so-called war on terrorism has created an institutional opportunity to regain lost ground in internal security operations, where the TNI has again become the dominant actor.31Jun Honna, “The Politics of Securing Khaki Capitalism in Democratizing Indonesia,” in Khaki Capital: The Political Economy of the Military in Southeast Asia, eds. Paul W. Chambers and Napisa Waitoolkiat, 305-327 (Copenhagen: NIAS, 2017). In recent years, TNI personnel and equipment have been increasingly deployed for non–defense-related missions, claimed as the manifestation of so-called MOOTW (Military Operations Other Than War, Operasi Militer Selain Perang). The military was able to decide its own mission profile and to reinvent new non–defense-related missions, which further expanded from its pre-existing capacity as state defense apparatus.32Aditya Batara Gunawan, “Indonesia: The Military’s Growing Assertiveness on Nondefense Missions,” in Civil-Military Relations: Control and Effectiveness Across Regimes, eds. Thomas C. Bruneau and Aurel Croissant, 141-158 (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2019). The extension of MOOTW beyond its pre-existing capacity has raised public concern over a potential revival of the military’s socio-political function in post-reformasi Indonesia. Moreover, as critics point out, it is also counterproductive to military effectiveness in key missions. It is hard to imagine that TNI will be able to maintain its warfighting role against external threats while devoting much of its resources to missions beyond TNI pre-existing capacity without limitation.33Gunawan, “Indonesia.” Furthermore, the Ministry of Defense is still under strong military influence, and parliamentary oversight of defense affairs is minimal. From a civilian perspective, allowing the military to define its own non-defense mission and shielding the mission from effective oversight may harm legitimation of democratically elected civilians in Indonesia.34Gunawan, “Indonesia.” Finally, former military officers (or purnawirawan) play an increasingly important role in electoral and party politics and have again gained access to patronage politics in both parliaments and political parties. Even though the power of purnawirawan is limited to individuals, critics worry that it could provide new opportunities for the military to maintain its economic and political interests.35M. Faishal Aminuddin, “The Purnawirawan and Party Development in Post-Authoritarian Indonesia, 1998–2014,” Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs 36, no. 2 (2017), 3-30. In the longer term, this holds huge potential to disrupt the future of the democratic system in the country.

Thailand: Failure and Collapse of Civil-Military Relations

The Kingdom of Thailand is another Southeast Asian country with a strong praetorian tradition. From 1932 to the mid-1970s, civilian bureaucrats and military elites dominated Thai politics, whereas the monarchy lent legitimacy to the military-bureaucratic elites.36Fred W. Riggs, Thailand: The Modernization of a Bureaucratic Polity (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1966). In the 1980s, an electoral authoritarian regime emerged in which political parties played an increasingly relevant role. Simultaneously, the palace regained political influence and power by forging “a modern form of monarchy as a para-political institution,” described as the “network monarchy.”37Duncan McCargo, “Network Monarchy and Legitimacy Crises in Thailand,” Pacific Review 18 (2005), 499-519. In May 1992, mass protests against military-backed Prime Minister Gen. (ret.) Suchinda Kraprayoon forced the armed forces to withdraw and to be content with its behind-the-scenes influence. While the now thoroughly “monarchised”38Paul W. Chambers and Napisa Waitoolkiat, “The Resilience of Monarchised Military in Thailand,” Journal of Contemporary Asia 46 (2016), 425-444. military maintained a “low-key political presence”39N. John Funston, “Thailand: Reform Politics,” in Government and Politics in Southeast Asia, ed. N. John Funston, 328-371 (Singapore: ISEAS, 2006), 348. after the transition to parliamentary democracy in 1992, it still was outside of parliamentary oversight and remained a political force through its linkages, both as an institution and as individuals, to political parties and to the monarchy. Democratic civil-military relations were to be realized only to the extent that they did not threaten the position of the “network monarchy” or the ideas that underpinned its power.40Kevin Hewison and Kengkij Kitirianglarp, “Thai-style Democracy: The Royalist Struggle for Thailand’s Politics,” in Saying the Unsayable: Monarchy and Democracy in Thailand, eds. Soren Ivarsson and Lotte Isager, 179-203 (Copenhagen: NIAS Press, 2010), 180. This became obvious during the premiership of Thaksin Shinawatra (2001–2006), who attempted to sever the relationship between the monarchy and the military and to turn the latter into a tool of his personal rule. However, this ultimately brought the confrontation between the military leadership and Thaksin to a head and culminated in the 2006 coup d’état.41Ukrist Pathmanand, “A Different Coup d’État?,” Journal of Contemporary Asia 38 (2008): 124-142. Even though the military allowed free parliamentary elections in December 2007 and handed power back to an elected government, military leaders continued to intervene whenever they deemed necessary for their own benefit or to defend the monarchy. Most importantly, on May 22, 2014, the army, led by Army Chief Prayuth Chan-ocha, staged a coup d’état against Prime Minister Yinluck Shinawatra, Thaksin’s sister.

The 2006 and 2014 coups were staged by military officers claiming deep loyalty to the monarchy. Yet the two putsches differ from previous coups as well as from each other. A first difference is that the political role of the military since the 1940s had been justified in terms of the defense of national institutions and later stressed rampant government corruption, the emergence of deep divisions in society, and attacks on the military.42Yoshifumi Tamada, “Coups in Thailand, 1980–1991: Classmates, Internal Conflicts and Relations with the Government of the Military,” Southeast Asian Studies 33 (1995): 317-339. In 2006, however, the coup leaders justified their actions as a means to “restore democracy,” whereas in 2014 the narrative of returning the country to order and defending the monarchy was dominant.43Pathmanand, “Different Coup d’État”; Chambers and Waitoolkiat, “Monarchised Military.” Second, since the late 1970s, post-coup constitution-making has been followed by elections that marked the return to “civilian” rule. The 2006 coup fits this pattern. However, since the 2014 coup, the military has maintained a tight grip on power, even though the long-promised elections took place in March 2019. This reflects a lesson that the coup plotters of 2014 have drawn from the failure of the previous military government to neutralize the pro-Thaksin movement. This and the extensive prerogatives of the military and monarch in the 2017 constitution suggest that the “monarchized military” wants to preserve its role as the guardian of the monarchy, state, and nation after the return to elections and (quasi-)civilian cabinets.

Comparison

The experiences of Indonesia and Thailand highlight the considerable persistence of civil-military relations and underscore the crucial importance of historical legacies and path dependence. This is especially true for Thailand, where the military has been able to carve out substantial political niches or take over the government since the 1930s. The transformation of civil-military relations cuts deeper and is more advanced in Indonesia, and it is not a coincidence that the stability and legitimacy of the existing political order is less contested compared to Thailand. A striking difference between the two countries is that in Thailand, the military government dictated the transition (both in 1992 and 2007, and, again, in 2019), whereas in Indonesia the military was “only” able to negotiate the terms of its own retreat from the center of the political stage. This left the Thai military—backed by the monarchy—in a much stronger position to keep reserved domains and veto power over the political process. While the Thai military still views itself as the proclaimed guardian of king and nation, in Indonesia, civilian control has been established on the national level in the crucial areas of elite recruitment and public policy. However, civilian control over internal security, national defense, and military organization remains under-institutionalized and continues to depend on the ability of the incumbent president to co-opt the military leadership into his (or her) personal patronage and loyalty networks. Unlike in Thailand, where the military’s deep entrenchment in society, the economy, and politics contributes to a vicious cycle of elections, political instability, and military enforcement, the chance of the armed forces in Indonesia returning to direct rule is slim, as soldiers have largely withdrawn from the political arena. In contrast, the Thai case is a reminder that militaries find it easier to block transitions from military autonomy to civilian supremacy if the democratic government fails to produce effective government, or if important groups desert the pro-democracy coalition. Despite the many shortcomings of democracy in Indonesia, one if not the most remarkable achievement of democratic consolidation in Indonesia is that adherence to essential democratic norms and procedures, and inclusionary coalition politics by political party elites, have become largely uncontested parameters for the political process in the country.

Transition and Transformation of Civil-Military Relations: Myanmar in Comparative Perspective

Transition qua military order

After 1990, the short-term goal for the military government was to ensure its own survival in power, whereas its longer-term goal was “to put into place all necessary means to guarantee that the Tatmadaw would remain the real arbiter of power in Myanmar” after a handover of government to the civilians.44Andrew Selth, Burma’s Armed Forces: Power without Glory (Norwalk, CT: Eastbridge, 2002), 33. For that purpose, the Tatmadaw first contained more immediate threats from insurgents and dissident groups. The regime also expanded its propaganda activities to portray the military as the only reliable and functioning national institution,45Tin M. M. Than, “Myanmar: Military in Charge,” in Government and Politics in Southeast Asia, ed. N. John Funston, 203–251 (Singapore: ISEAS, 2006) 245; David Steinberg, “Legitimacy in Burma/Myanmar: Concepts and Implications,” in Myanmar: State Society and Ethnicity, eds. Narayanan Ganesan and Kyaw Y. Hlaing, 109-142 (Singapore: ISEAS, 2007), 126. and gave up any socialist claim of transforming society in favor of a limited phase of military transitional rule with the official aim of establishing a “disciplined democracy.”46 Robert H. Taylor, “ ‘One day, one fathom, bagan won’t move’: On the Myanmar Road to a Constitution,” in Myanmar’s Long Road to National Reconciliation, ed. Trevor Wilson, 3-28 (Singapore: ISEAS, 2006), 21. In 2003, the military’s long-term planning resulted in the introduction of a seven-point “roadmap” as a plan for a controlled transition to “disciplined democracy.”47Andrew Selth, “All Going According to Plan? The Armed Forces and Government in Myanmar,” Contemporary Southeast Asia, 40, no. 1 (2020): 1-26. Ceasefire agreements with around 30 rebel groups and the failure of nonviolent anti-incumbent mass protests in 2007 (“Saffron Revolution”) signaled the extent to which the military had managed to realize this aim.

From a position of relative strength, the Tatmadaw introduced a new political structure that relieved the military of the routine of government while disguising its continued control of the country’s more important political processes.48Selth, “All Going According to Plan.” In 2008, the military government presented a new constitution that grants the Tatmadaw immense political prerogatives, imposes severe constraints on the functioning of the future political regime, and protects their personal and corporate interests after leaving power.49Melissa Crouch, “Pre-emptive Constitution-Making: Authoritarian Constitutionalism and the Military in Myanmar,” Law & Society Review 54, no. 2 (2020): 487-515. The 2008 constitution reaffirms the leading role of the military as the guardian of the constitutional order, national integrity, and the sovereignty of the Union. Under the constitution, the Tatmadaw is de facto an independent fourth branch of government that has the right to administer and adjudicate all military affairs itself. Its business activities are excluded from legal or parliamentary oversight, and it claims the lion’s share of the country’s economic resources. It appoints the defense, home, and border affairs ministers both in the national cabinet and in the regional governments. It also has the right to veto decisions of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of the government as far as national security, defense, or military policy is concerned. Members of the Tatmadaw enjoy full impunity for any actions taken under the government of the State Peace and Development Council (Art. 445), and members of the armed forces can only be tried by the military court system. Furthermore, the armed forces have constitutionally secured a quarter of all seats in the Union parliament and in the 14 state and regional legislative assemblies, which guarantees the military a veto over any prospects of constitutional change. The Tatmadaw’s commander-in-chief appoints and removes the military members of parliament and the ministers of defense, home, and border affairs as well as the ministers for border security in the subnational governments (Art. 232). He commands all military units, paramilitary forces, and border troops, has to confirm the appointment of any additional military cabinet member, and can reverse any decision by the military courts (Art. 343). In case a state of emergency is declared, all legislative and executive powers are transferred to the military commander-in-chief (Art. 40, 149). Finally, the military controls the National Defense and Security Council, an 11-member group that must approve the declaration of a state of emergency and appoints the commander-in-chief. In addition, the Tatmadaw’s practice of transferring military officers into civilian positions in government ministries or into the judiciary, and the existence of a military-aligned opposition party, the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), provide indirect or informal means to monitor and capture civilian institutions at the national and subnational levels.

The sham elections in November 2010 and the formation of a government under President Thein Sein, a former general, in 2011 completed the transition from direct military rule to multiparty authoritarianism under military tutelage. Since then, important political reforms followed, including a national dialogue with opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi and the 2015 general elections, in which the NLD won a majority of seats in the bicameral Union legislature.

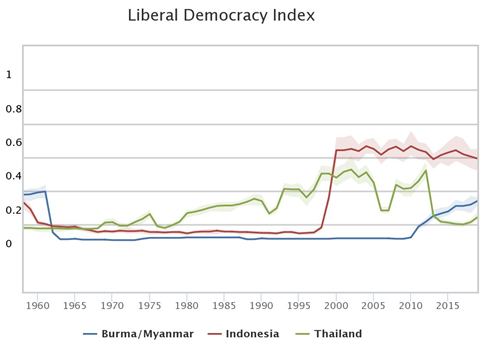

Even though the post-2015 political regime fell short on democratic minima, and there had been an erosion of minority rights as well as reports of increasing suppression of civil liberties and political rights by the elected government in recent years,50Adam Simpson and Nicholas Farrelly, “The Rohingya Crisis and Questions of Accountability,” Australian Journal of International Affairs, 74, no. 5 (2020): 486-494. the post-2015 political environment was more democratic and more liberal than it used to be at any time between 1962 and 2010 (see Figure 1).

Note: The Liberal Democracy Index from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project has a range from 0 to 1 (higher values indicate higher levels of democracy). The indices measure the extent to which liberal democracy in its fullest sense is achieved.51Michael Coppedge et al., “V-Dem [Country–Year/Country–Date] Dataset v10,” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project, https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemds20. March 8, 2021.

While not the only shortcomings in terms of democratization, many of the democratic defects of the political system were related in one way or the other to the tutelary role of the Tatmadaw. Evidently, having competitive elections with genuine opposition parties was not sufficient for a fuller transition from democratic government in Myanmar.

Myanmar in Comparative Perspective

A striking similarity between the transitions from a military-led autocracy toward “something else”52Guillermo A. O’Donnell and Philippe C. Schmitter, Tentative Conclusions about Uncertain Democracies (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986). in Indonesia, Thailand, and Myanmar has been reform through extrication, whereby the military government dictated the transition (Thailand and Myanmar) or, at least, was able to negotiate the terms of its retreat from the center of the political stage (Indonesia). Despite this, there are a number of crucial differences between Myanmar on the one hand and the other two Southeast Asian nations on the other.

First, in contrast to Thailand’s vicious cycle of civilian governments and military interventions, and Indonesia, where the armed forces became sidelined by the dictators during the final years of the authoritarian order, the Tatmadaw controlled the political center and ruled Myanmar for more than five decades. The long period of uninterrupted military rule effectively reduced state agencies to “medieval fiefdoms”53Chao-Tzang Yawnghwe, “The Politics of Authoritarianism: The State and Political Soldiers in Burma, Indonesia, and Thailand” (PhD diss., University of British Columbia, 1997), 97. that “responded less and less to rational-legal norms, and increasingly to the ‘logic’ of opaque, patrimonial military politics and intrigues.”54Yawnghwe, “Politics of Authoritarianism,” 97. After the return to direct military rule in 1988, the Tatmadaw created a new institutional structure that extended direct and complete military control over all important state functions at the national and subnational level.55Than, Myanmar, 225; Robert H. Taylor, The State in Myanmar, 2d ed. (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2009), 394. Thereby, the Tatmadaw evolved from an agent of the state into the state itself.

Second, in all three countries, military officers and units had played an important role in their national economy since the 1950s. However, Myanmar stands out as the one case where the military became the most significant single player in the national economy. In the 1990s, the military abandoned the experiment with a socialist planned economy in favor of military-dominated rentier capitalism, allowed regional commanders and military units to pursue their own business interests,56Maung A. Myoe, “A Historical Overview of Political Transition in Myanmar since 1988,” Working Paper 95 (Singapore: National University of Singapore, 2007); Kevin Hewison and Susanne Prager Nyein, “Civil Society and Political Opposition in Burma,” in Myanmar: Prospect for Change, eds. Li Chenyang and Wilhelm Hofmeister, 13-34 (Singapore: Konrad Adenauer Foundation, 2009); Lee Jones, “The Political Economy of Myanmar’s Transition,” Journal of Contemporary Asia, 44 (2013): 144-170, here 149. and strengthened direct military control over the most lucrative branches of the national economy. The resulting mélange of military, rebel, and civilian businesses further weakened state institutions and strengthened the exploitative nature of the military-dominated economic system.57Jones, “Political Economy.” As a result, the 1990s saw the creation and expansion of a number of military-owned conglomerates, such as the Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings Limited and the Myanmar Economic Corporation, and private companies owned by military officers or their civilian cronies.58Marco Bünte, “The NLD–Military Coalition in Myanmar: Military Guardianship and Its Economic Foundations,” in Khaki Capital: The Political Economy of the Military in Southeast Asia, eds. Paul W. Chambers and Napisa Waitoolkiat, 93-129 (Copenhagen: NIAS, 2017), 117-118.

Third, military rule in Myanmar was the result of a “corporative coup”59Brooker, “Non-democratic Regimes.”: The resulting “hierarchical military regimes”60Linz and Stepan, “Problems of Democratic Transition.” included all services and relevant power groups within the Tatmadaw, which made sure no individual faction would be able to undermine the power base of the military government within the military-as-institution.61Aurel Croissant and Jil Kamerling, “Why Do Military Regimes Institutionalize? Constitution-making and Elections as Political Survival Strategy in Myanmar,” Asian Journal of Political Science 21(2013): 105-125. While factional struggles within the military between informal yet close-knit and homogenous cliques are an essential feature of the Royal Thai Armed Forces,62Paul W. Chambers, Knights of the Realm: Thailand’s Military and Policy Then and Now (Bangkok: White Lotus Press, 2013). and conflicts between marginalized officers and military clients of President Suharto contributed to the downfall of Indonesia’s New Order regime in 1998,63Lee, “Defect or Defend.” the durability of military rule in Myanmar was intimately linked to the ability of military elites since the 1960s to create a well-organized and cohesive military institution, solving credible commitment problems between military factions, maintaining respect for hierarchy among officers, and avoiding the characteristic instability of military regimes.

Fourth, the political identity of the Tatmadaw is much different from the TNI or the Royal Thai Armed Forces. In Thailand, the power and legitimacy of the military as a political force has been time and again contested and rests as much or more on the ability to contest the authority of (civilian) authorities as on the use of institutionalized prerogatives. The “soft power” of the Thai military and its ability to legitimize an interventionist political role have significantly changed since the mid-1970s. The thoroughly monarchized military relies very much on the (waning) legitimacy of the palace and is widely perceived as a protective agent of the royal principal. In contrast to the era of the bureaucratic policy (1932–1973), the political and ideological power of the Thai military has become dependent on its allegiance to a monarchy who has become the central impediment of Thai national identity, but whose domestic hegemony is clearly in decline.64Kaisan Tejapira, “The Irony of Democratization and the Decline of Royal Hegemony in Thailand,” Southeast Asian Studies 5, no. 2 (August 2016): 291-237. In Indonesia, one of the key factors behind the nation’s democratic stability is the consensus among the relevant civilian elites, military leaders, and the public to sideline the TNI from the political decision-making process of the country. The military reform agenda in post-Suharto Indonesia successfully removed the dual-function doctrine (dwifungsi) that served as the basis of TNI’s socio-political role during the dictatorship, further establishing professionalism as the new military identity. Despite worries about a possible “greening” of the TNI in the 1990s,65Rinakit, “Indonesian Military.” the Indonesian military remained a bastion of secular nationalism in the republic.

By contrast, the Tatmadaw has never seen itself as having separate military and sociopolitical roles, with the first naturally having primacy over the second. However, the Tatmadaw sees itself as the protector of Myanmar’s dominant Buddhist culture.66Crouch, “Pre-emptive Constitution-Making.” The Tatmadaw’s prerogatives and central place in national life are independent of the existence of other, non-military institutions or sociopolitical actors. And while the Thai military is forced to participate in party politics in order to exercise control over parliament and cabinet, the Tatmadaw’s direct and indirect means of political control do not rest on the existence of a strong proxy party.67Although the USDP is known as a proxy party for the Tatmadaw, reserved representation of military delegates in national and subnational legislatures and other prerogatives of the armed forces guarantee the Tatmadaw can preserve its political clout even without having a strong “civilian” political party at its disposal. Moreover, protracted military hegemony and recent liberalizations are inextricably interwoven in the country’s multiple and protracted intrastate conflicts. The military-led reform process has followed a sequential logic that follows from the Tatmadaw’s imperatives, where state security and stability are prerequisites for economic liberalization, electoral democracy, and peace negotiations. As Stokke and Aung note, this approach to political reforms has created new democratic spaces but also prevented the emergence of more “substantive popular control of public affairs.”68Kristian Stokke and Soe Myint Aung, “Transition to Democracy or Hybrid Regime? The Dynamics and Outcomes of Democratization in Myanmar,” European Journal of Development Research 32, no. 2 (2020): 274-293, here 277.

2021: Paradox and Puzzle

The paradox of regime transition in Myanmar is that political reforms were planned and executed by the Tatmadaw. Civilian acquiescence of military safeguards and restrictions on the effective power to govern democratically legitimized institutions made regime change possible in the first place. However, any robust attempt by the elected executive and legislature to abolish military prerogatives—for example, to trim military resources or to remove articles from the constitution that effectively grant immunity from prosecution for human rights violation—could, at best, be easily blocked by the military. At worst, it would possibly trigger another military intervention that could result in a renewed shutdown of the political system. Even though the political landscape of Myanmar had changed significantly since 2011, the Tatmadaw remained the country’s most powerful political actor. A democratically elected government coexisted with a military whose reserved domains and veto powers were far more extensive than everything the Indonesian military ever was able to control during Suharto’s New Order and in the post-1999 reformasi era. This does not mean that there is no space for further political reforms. Even in post-2015 Myanmar, law-making was the prerogative of the legislature, and despite the continued military dominance in the political and economic sphere, there is scope for change. This was best illustrated by the NLD-led government’s successful move to bring the nation’s main public administration body—the General Administration Department—under civilian control in December 2018. 69David Brenner and Sarah Schulman, “Myanmar’s Top-Down Transition: Challenges for Civil Society,” IDS Bulletin 50, no. 3 (2019):17-36; here 23. However, unlike Thailand, where the military felt compelled to repeatedly threaten, challenge, or unconstitutionally remove elected government to protect its own interests and those of its allies in society and the palace, the institutionalized prerogatives of the Tatmadaw proved sufficient to avoid having to resort to extreme forms of contestation—at least until the coup d’état of February 1, 2021.

Why, then, did the military execute another coup d’état in early February of this year, when the generals continued to monopolize control over coercion, controlled vast portions of the national economy, and possessed the ultimate authority to block any changes of the constitutional order, while at the same time successfully avoiding most of the international blame for what was wrong in the country, including the atrocities against ethnic and religious minorities that had continued after 2015?

As many observers have pointed out, the USDP, which is the Tatmadaw’s proxy party, fared poorly in the national elections of November 2020, and the coup d’état was staged as the newly elected parliament was set to open. In the months following the election, the military had backed claims of widespread fraud by the USDP and other opposition parties, such as the new Democratic Party of National Politics (DNP),70The DNP was formed by allies of former General Than Shwe, who had ruled the country from 1992 to 2011. and their demand for a “rerun” of the election.71In the days before the coup, the Tatmadaw declared that more than eight million cases of potential voting fraud had been uncovered relating to the November election (Jack Goodman, “Myanmar Coup: Does the Army Have Evidence of Voter Fraud?,” BBC, February 5, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/55918746). Perhaps inspired by the events in the United States, there were also claims on social media that Myanmar had used Dominion Voting Systems in the general election (Reuters, “Fact Check: Myanmar Did Not Use Dominion Voting Systems in General Election,” Reuters, February 2, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-factcheck-dominion-myanmar-idUSKBN2A22ZO). There is no proof for the first claim. The second one is simply wrong. Although it is not terribly plausible to assume that the Tatmadaw suddenly became a champion of electoral integrity and the national election commission had validated the NLD victory, allegations of electoral fraud provided a convenient rationale to prevent parliament from convening and confirming the NLD government.

The imminent opening of parliament might explain the timing of the intervention but not why the military deemed such a dramatic measure necessary to protect its interests in the first place. Reserved representation of military delegates in national and subnational legislatures and other prerogatives of the armed forces guarantee the Tatmadaw can preserve its political clout even without having a strong “civilian” political party at its disposal. Another explanation, favored by some foreign analysts, is that the coup basically reflects the personal ambition of General Min Aung Hlaing, commander-in-chief of the Tatmadaw and head of the new military government. Because Min Aung Hlaing, who had already overstayed mandatory retirement for military officers by five years, was up for retirement in July 2021, it was widely believed that he had ambitions to become president. 72Kyaw Zwa Moe, “How Myanmar’s Military Chief Could Become President,” The Irrawaddy, September 23, 2019, https://www.irrawaddy.com/opinion/commentary/myanmars-military-chief-become-president.html; Hein Myat Soe, “The Game of Myanmar’s Senior General,” Myanmar Times, February 19, 2020, https://www.mmtimes.com/news/game-myanmars-senior-general.html. Though not implausible, it seems unlikely—given the likelihood of international criticism and, especially, domestic mass protest—that the whole armed forces would take such a potentially high-cost, high-risk step to satisfy the personal ambitions of a single senior general. A third and in combination with the other two explanations perhaps more plausible reading of the events of February 1, 2021, is that the coup d’état is the outcome of failed brinkmanship in a bargaining situation that was characterized by mutual distrust and limited information. It is important to keep in mind that, as Milan Svolik shows in his brilliant study into the origins of military dictatorship, military coups usually are an outcome of failed “brinkmanship bargaining.”73Milan W. Svolik, The Politics of Authoritarian Rule (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 36. Following Schelling, he defines brinkmanship as a bargaining strategy that uses threats “that leave something to chance.”74Thomas C. Schelling, The Strategy of Conflict (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1960), 187-206. According to Svolik:

the distinct feature of this interaction between the government and the military entails the conscious manipulation of the risk of an overt military intervention—an outcome that both parties prefer to avoid. […] The military cannot credibly “draw a line in the sand” and claim that it will intervene if that line is crossed; the government cannot credibly feign complete ignorance of the military’s capacity to use force. In turn, both resort to brinkmanship and bargain by “rocking the boat.”75Svolik, Politics of Authoritarian Rule, 135-136.

Military intervention, then, occurs when, in a “push-and-shove play for influence between the military and the government, the latter oversteps and ‘rocks the boat’ too much.”76Svolik, Politics of Authoritarian Rule, 125. For years, the NLD had tried to move forward with its reform agenda while avoiding pushing too hard for institutional or policy concessions from the military and potentially kindling a coup. However, according to multiple reports and comments by domestic observers, the relationship between State Councillor Aung San Suu Kyi and military leader Min Aung Hlaing had gone from bad to worse following the November election, when the NLD rejected the Tatmadaw’s request to investigate alleged election fraud.77Megan Ryan and Darin Self, “Myanmar’s Military Distrusts the Country’s Ruling Party. That’s Why It Staged a Coup and Detained Leaders and Activists,” Washington Post Monkey Cage, February 2, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/02/02/myanmars-military-detained-dozens-top-leaders-hundreds-lawmakers-are-under-house-arrest/. Adding to the breakdown of communication between the two leaders were possibly real grievances among the top military officers about the perceived lack of attention and respect for their concerns and views, as well as real concern that the NLD government might consider the party’s landslide victory in the November election as a chance to step up their efforts to overcome some of the legacies of the military-controlled transition.78Van Tran, “Order from Chaos. To Understand Post-coup Myanmar, Look to Its History of Popular Resistance—Not Sanctions,” Brookings Institute, February 9, 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2021/02/09/to-understand-post-coup-myanmar-look-to-its-history-of-popular-resistance-not-sanctions/; Ryan and Self, “Myanmar’s Military.” According to some reports, there were Chinese-brokered negotiations between Min Aung Hlaing and Suu Kyi’s envoys in the days before the coup.79Michael W. Charney, “Myanmar Coup: How the Military Has Held onto Power for 60 Years,” The Conversation, February 3, 2021, https://theconversation.com/myanmar-coup-how-the-military-has-held-onto-power-for-60-years-154526; Helen Regan, “Why the Generals Really Took Back Power in Myanmar,” CNN, February 8, 2021, https://edition.cnn.com/2021/02/06/asia/myanmar-coup-what-led-to-it-intl-hnk/index.html. The straw that finally broke the camel’s neck was that the NLD representatives refused to budge to military demands. Faced with the choice of yielding or taking action, the military leadership opted for the latter.

Conclusions

Democratization is neither a linear nor a teleological process. The consolidation of democracy in a particular country does not preclude the possibility that this process can slow down, come to a halt, or be reversed. Indeed, in countries struggling with the transition from a certain authoritarian regime toward something uncertain, it might not be enough to reduce the privileges or prerogatives of the military; it is necessary to redefine the tasks and nature of the armed forces. This is especially true for Indonesia, Thailand, and Myanmar, where the military was able to carve out substantial political niches or took over the government shortly after the countries’ independence or emergence as modern nation-states. Even in Indonesia, arguably the most successful case of democratization in Southeast Asia in the early 21st century, civilian control remains incomplete and weakly institutionalized.

What can be learned from this analysis? A first conclusion and, perhaps, the most obvious finding is that, the optimal strategy of reforming civil-military relations after extrication from military rule is inconsistent. The forces pushing for democracy must be prudent before the transition from military government to civilian government, and they ought to be resolute after this transition has taken place. But decisions made during the first transition create conditions that are hard to reverse in the second transition, since they preserve the power of forces associated with the old regime.80Przeworski, Democracy and the Market.

Second, the experiences of other countries suggest that political stability through compromise will be crucial for future democratic change in civil-military relations and the political system at large. Presumably the most crucial prerequisite for building democratic civil-military relations is ensuring political stability via strong civilian leadership with stable and transparent political institutions. In successful cases such as South Korea and Indonesia, pro-democracy reformers were able to build strong leadership and bargaining leverage vis-à-vis the praetorian army through elite compromise among old conservatives and new reformists as well as by creating trust between civilian and military elites.81Croissant et al., Democratization and Civilian Control.

Third and related to the previous conclusions is the assumption that in cases of extrication from military government, such as Myanmar, in which democratically elected governments have to coexist and cooperate with a military that enjoys far-reaching and strong prerogatives, veto powers, and blackmailing potential vis-à-vis the civilian government, successful reforms can only be achieved together with (and not against) the military. Hence, unilateral reform attempts are inadvisable. Even though civilians might be forced to spend much of their most precarious resources—that is, time and political capital—and although it might sometimes be a frustrating undertaking, the key to successful military reform is to create sufficiently broad change coalitions including leaders from political society, civil society, and the military.

Fourth, slow and sometimes limited democratic transition can bring about a more desirable outcome than revolutionary changes—at least in terms of civil-military relations. Swift and drastic changes are inadvisable because they might unnecessarily provoke the ire of those for whom regime change means the loss of their power and privileges. A gradualist approach that favors coalition-building and a willingness to make acceptable compromises is usually a prudent way to proceed. Pro-democracy reformists are too often impatient and rush into hasty reforms of military and security institutions—in many cases without a proper understanding of the nature of the military as a national security institution. That is not to say that the “blame” for the February coup lies entirely or largely with the NLD and its leader. But it is evident that civil-military reforms in Myanmar are much more challenging than in most other countries and, hence, there is a special need for prudence.

Given the deep entrenchment of the military in the political and economic system, the legacies of military rule and military control over the first transition, and extremely difficult context conditions such as ongoing ethnic conflicts, Myanmar will most probably have to live with military prerogatives and tutelary power even after a return to the status quo ante. Civilian governments and institutions will most likely have neither capabilities nor opportunities to push for quick and deep changes in civil-military relations. Nor should they wish for it: If change is possible, it can probably come only through gradual and incremental reforms.

Notes

- 1David Steinberg, “Myanmar elections another step towards democracy?,” East Asia Forum, October 25, 2020, https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2020/10/25/myanmar-elections-another-step-towards-democracy/.

- 2Robert M. Fishman, “Rethinking State and Regime: Southern Europe’s Transition,” World Politics 42 (1990): 422–440; here 428.

- 3Svend E. Skaaning, “Political Regimes and Their Changes: A Conceptual Framework,” Working Paper 55 (2006): 1–29, https://cddrl.fsi.stanford.edu/publications/political_regimes_and_their_changes_a_conceptual_framework, here 15.

- 4David Collier, Fernando Daniel Hidalgo, and Andra Olivia Maciuceanu, “Essentially Contested Concepts: Debates and Applications,” Journal of Political Ideologies 11, no. 3 (2006), https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13569310600923782.

- 5Robert Dahl, Democracy and Its Critics (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1989), 250.

- 6Paul Brooker, Non-Democratic Regimes, 2d ed. (Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009); Barbara Geddes, Joseph Wright, and Erica Frantz, How Dictatorships Work. Power, Personalization, and Collapse (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 2018); Barbara Geddes, Joseph Wright, and Erica Frantz, “Military Rule,” Annual Review of Political Science 17 (2014): 147-162.

- 7Guillermo A. O’Donnell, “Transitions, Continuities, and Paradoxes,” in Issues in Democratic Consolidation: The New South American Democracies in Comparative Perspective, ed. Scott Mainwaring, 17-56 (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1992).

- 8O’Donnell, “Transitions, Continuities,” 18.

- 9Adam Przeworski, “Democracy and the Market: Political and Economic Reforms in Eastern Europe and Latin America,” in The Democracy Sourcebook, eds. Robert A. Dahl, Ian Shapiro, and José A. Cheibub, 76-92 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003), 81-85.

- 10Aurel Croissant, David Kuehn, Philip Lorenz, and Paul W. Chambers, Democratization and Civilian Control in Asia (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013).

- 11Alfred Stepan, Rethinking Military Politics: Brazil and the Southern Cone (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988), 93.

- 12David Kuehn, “Theoretical Landscape,” in Civil-Military Relations: Control and Effectiveness Across Regimes, eds. Thomas C. Bruneau and Aurel Croissant, 19-34 (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2019).

- 13Muthiah Alagappa, “Introduction,” in Coercion and Governance: The Declining Political Role of the Military in Asia, ed. Muthiah Alagappa, 1-28 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001); Mark Beeson and Alex J. Bellamy, Securing Southeast Asia: The Politics of Security Sector Reform (London: Routledge, 2008).

- 14Abel Escribá-Folch, “Authoritarian Responses to Foreign Pressure: Spending, Repression, and Sanctions,” Comparative Political Studies 45, no. 6 (2012): 683-713.

- 15Zoltan Barany, The Soldier and the Changing State: Building Democratic Armies in Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Americas (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012); Timothy M. Edmunds, “Security Sector Reform,” in Routledge Handbook of Civil-Military Relations, eds. Thomas C. Bruneau and Florina Cristiana Matei, 48-60 (London: Routledge, 2012).

- 16Narcís Serra, The Military Transition: Democratic Reform of the Armed Forces (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 241.

- 17David Pion-Berlin, “Foreword,” in Who Guards the Guardians and How: Democratic Civil-Military Relations, eds. Thomas C. Bruneau and Scott D. Tollefson, iii-xiv (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006).

- 18Eliot Cohen, “Change and Transformation in Military Affairs,” Journal of Strategic Studies 27, no. 3 (2004): 395-407.

- 19Pion-Berlin, “Foreword.”

- 20Felipe Agüero, “Legacies of Transitions: Institutionalization, the Military, and Democracy in South America,” Mershon International Studies Review 42 (1998): 383-404; Juan J. Linz and Alfred Stepan, eds., Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation: Southern Europe, South America, and Post-communist Europe (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996).

- 21David Kuehn and Aurel Croissant, “Civilian Control and Democratization in the Third Wave: Routes to Reform,” unpublished manuscript, 2020.

- 22Kuehn and Croissant, “Civilian Control.”

- 23Dan Slater, Ordering Power: Contentious Politics and Authoritarian Leviathans in Southeast Asia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010); John Gledhill, “Competing for Change: Regime Transition, Intrastate Competition, and Violence,” Security Studies 21 (2012): 43-82.

- 24Gregory Vincent Raymond, “Naval Modernization in Southeast Asia: Under the Shadow of Army Dominance?” Contemporary Southeast Asia 39 (2017): 149-177; here 162.

- 25Sukardi Rinakit, The Indonesian Military after the New Order (Singapore: NIAS Press, 2005).

- 26Lesley McCulloch, “Trifungsi: The Role of the Indonesian Military in Business,” in The Military as an Economic Actor: Soldiers in Business, eds. Jörn Brömmelhörster and Wolf-Christian Paes, 94-123 (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2003).

- 27Ross McLeod, “Inadequate Budgets and Salaries as Instruments for Institutionalizing Public Sector Corruption in Indonesia,” South East Asia Research 16 (2008): 199-223; here 200; Terence Lee, Defect or Defend: Military Responses to Popular Protests in Authoritarian Asia (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015).

- 28Dan Slater, “Altering Authoritarianism: Institutional Complexity and Autocratic Agency in Indonesia,” in Explaining Institutional Change: Ambiguity, Agency, and Power, eds. James Mahoney and Kathleen Thelen, 132-167 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 133.

- 29Marcus Mietzner, Military Politics, Islam, and the State in Indonesia: From Turbulent Transition to Democratic Consolidation (Singapore: ISEAS, 2009).

- 30Philip Lorenz, “Principals, Partners and Pawns: Indonesian Civil Society Organizations and Civilian Control of the Military” (PhD diss., University of Heidelberg, 2015).

- 31Jun Honna, “The Politics of Securing Khaki Capitalism in Democratizing Indonesia,” in Khaki Capital: The Political Economy of the Military in Southeast Asia, eds. Paul W. Chambers and Napisa Waitoolkiat, 305-327 (Copenhagen: NIAS, 2017).

- 32Aditya Batara Gunawan, “Indonesia: The Military’s Growing Assertiveness on Nondefense Missions,” in Civil-Military Relations: Control and Effectiveness Across Regimes, eds. Thomas C. Bruneau and Aurel Croissant, 141-158 (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2019).

- 33Gunawan, “Indonesia.”

- 34Gunawan, “Indonesia.”

- 35M. Faishal Aminuddin, “The Purnawirawan and Party Development in Post-Authoritarian Indonesia, 1998–2014,” Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs 36, no. 2 (2017), 3-30.

- 36Fred W. Riggs, Thailand: The Modernization of a Bureaucratic Polity (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1966).

- 37Duncan McCargo, “Network Monarchy and Legitimacy Crises in Thailand,” Pacific Review 18 (2005), 499-519.

- 38Paul W. Chambers and Napisa Waitoolkiat, “The Resilience of Monarchised Military in Thailand,” Journal of Contemporary Asia 46 (2016), 425-444.

- 39N. John Funston, “Thailand: Reform Politics,” in Government and Politics in Southeast Asia, ed. N. John Funston, 328-371 (Singapore: ISEAS, 2006), 348.

- 40Kevin Hewison and Kengkij Kitirianglarp, “Thai-style Democracy: The Royalist Struggle for Thailand’s Politics,” in Saying the Unsayable: Monarchy and Democracy in Thailand, eds. Soren Ivarsson and Lotte Isager, 179-203 (Copenhagen: NIAS Press, 2010), 180.

- 41Ukrist Pathmanand, “A Different Coup d’État?,” Journal of Contemporary Asia 38 (2008): 124-142.

- 42Yoshifumi Tamada, “Coups in Thailand, 1980–1991: Classmates, Internal Conflicts and Relations with the Government of the Military,” Southeast Asian Studies 33 (1995): 317-339.

- 43Pathmanand, “Different Coup d’État”; Chambers and Waitoolkiat, “Monarchised Military.”

- 44Andrew Selth, Burma’s Armed Forces: Power without Glory (Norwalk, CT: Eastbridge, 2002), 33.

- 45Tin M. M. Than, “Myanmar: Military in Charge,” in Government and Politics in Southeast Asia, ed. N. John Funston, 203–251 (Singapore: ISEAS, 2006) 245; David Steinberg, “Legitimacy in Burma/Myanmar: Concepts and Implications,” in Myanmar: State Society and Ethnicity, eds. Narayanan Ganesan and Kyaw Y. Hlaing, 109-142 (Singapore: ISEAS, 2007), 126.

- 46Robert H. Taylor, “ ‘One day, one fathom, bagan won’t move’: On the Myanmar Road to a Constitution,” in Myanmar’s Long Road to National Reconciliation, ed. Trevor Wilson, 3-28 (Singapore: ISEAS, 2006), 21.

- 47Andrew Selth, “All Going According to Plan? The Armed Forces and Government in Myanmar,” Contemporary Southeast Asia, 40, no. 1 (2020): 1-26.

- 48Selth, “All Going According to Plan.”

- 49Melissa Crouch, “Pre-emptive Constitution-Making: Authoritarian Constitutionalism and the Military in Myanmar,” Law & Society Review 54, no. 2 (2020): 487-515.

- 50Adam Simpson and Nicholas Farrelly, “The Rohingya Crisis and Questions of Accountability,” Australian Journal of International Affairs, 74, no. 5 (2020): 486-494.

- 51Michael Coppedge et al., “V-Dem [Country–Year/Country–Date] Dataset v10,” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project, https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemds20. March 8, 2021.

- 52Guillermo A. O’Donnell and Philippe C. Schmitter, Tentative Conclusions about Uncertain Democracies (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986).

- 53Chao-Tzang Yawnghwe, “The Politics of Authoritarianism: The State and Political Soldiers in Burma, Indonesia, and Thailand” (PhD diss., University of British Columbia, 1997), 97.

- 54Yawnghwe, “Politics of Authoritarianism,” 97.

- 55Than, Myanmar, 225; Robert H. Taylor, The State in Myanmar, 2d ed. (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2009), 394