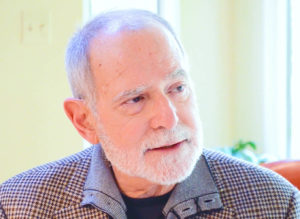

Our community is deeply saddened at the passing of Michael Krepon, co-founder of the Stimson Center and a tireless advocate for international peace and security.

Michael was an internationally renowned leader in the fight to prevent nuclear war and an eloquent advocate for pragmatic ways to reduce the threat that nuclear weapons pose to our civilization. For those who had the benefit of knowing him, he was a friend and mentor, a voice of conscience and kindness, and a stalwart advocate for the organization that has continued his legacy of leadership.

Videos

A Legacy of Achievement

It was in service to others that Michael found his calling, dedicating himself to protecting humankind from our worst impulses. He was an early and influential post-Cold War advocate for the complete elimination of nuclear weapons, helping to bring that idea into the mainstream. As President of the Stimson Center, with co-founder Barry Blechman, he played essential roles in the creation of the Open Skies Treaty, the permanent extension of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, and ratification of the Chemical Weapons Convention, each landmark achievements in their own right. Michael’s impact was also especially felt in South Asia, where he worked with a generation of leaders in both India and Pakistan to apply the lessons of the Cold War, build confidence between adversaries, and reduce the chance of nuclear war on the subcontinent. He was the author of 23 books, most recently Winning and Losing the Nuclear Peace: The Rise, Demise, and Revival of Arms Control, and countless papers and essays.

Remembrances

Please give us a day or two to post.

"It is with the deepest sadness that I learned of Michael’s passing. He taught me early in my career that there are no perfect solutions to the nuclear weapons problem and that we each can only do our part to leave things just a little better than we found them. I enjoyed every single interaction I had with Michael; he inspired a generation and will be missed."

Adam Scheinman

"Michael was a pioneering and caring leader and guiding force behind the Stimson Center -- and the dynamic community of scholar-practitioners it spawned over decades -- from its inception in 1989. From interns and the most junior new members of Team Stimson to long-time associates, he was always generous with his time and thoughtful advice based on decades of original and impassioned policy research. His prolific scholarship made a difference and will continue to have an impact, with global reach, for decades to come. The Stimson Community will miss Michael dearly but continue to take inspiration from the path-breaking example he set for both present and future generations of scholar-practitioners."

Richard Ponzio, Stimson colleague

"I had the great pleasure of working with Michael over the years. There are a lot of people with great skill and accomplishment in the DC world. But all too few who blend intensity and humility, commitment and compassion, as well as Michael did. Condolences to the Krepon family."

Bruce Jentleson

"I first met Michael in New Delhi, where I was in the embassy and Michael was on a trip to gather facts, share ideas, and stay in touch with his many contacts in the region. We had a nice conversation during which I am sure I learned more than he did.

I came to know Michael better when I joined the Board at Stimson. He was a thoughtful, insightful, knowledgeable, and strategic colleague for Board members and an inspirational and supportive colleague for the Stimson staff. Over the years at Stimson, I found that Michael always listened very carefully to others and, unlike many in Washington's policy community, did not speak unless he had something to say that would advance the discussion of which he was a part. He also had an excellent sense of humor.

Washington is full of smart people who care deeply about issues and are knowledgeable about them. In my view, what made Michael a special person was that he combined his knowledge and passion with real care for people, people he worked with, as well as people who live in troubled regions, and that care motivated and allowed him to build bridges of communications (and sometimes understanding) that led to progress and sometimes breakthroughs.

Michael will be remembered by all who knew him, in whatever capacity, and those who work on the issues to which he devoted his talents and life. He was a good man and he and his life's work made a difference."Ken Brill, Stimson colleague

"An immeasurable loss. Michael was an educator, author, advocate, mentor, co-founder – and a giant for nuclear peace. He was an advocate for for diplomacy and action. Even if the political conditions seemed daunting, he was a true believer — always positive that each step, big or small, was significant in moving forward. Cynicism blocks creativity, he would say, and in this business perseverance is key.

Michael leaves behind an incredibly bright light. His kindness was unbounded. Mentoring generations, encouraging new talent, and engaging in meaningful work are at the heart of his legacy. His is a celebration of life, his family, and Stimson.

It is up to us all to carry on his light and actively encourage policy to move forward. Onwards toward nuclear peace!"Cindy Vestergaard, Stimson colleague

"Michael’s sudden death is a dark and sad time for his family and friends. Please convey my deepest sympathy and condolences. But it is a tragedy for us who looked to him as a practical visionary for ways to prevent war and the threat weapons of mass destruction create. His last book, Winning and Losing the Nuclear Peace, is a comprehensive and masterful survey of the efforts governments and people made to use diplomacy and science to resolve conflicts and build enduring institutions for peace. It will stand as a memorial to his knowledge and wisdom in the service of policy.

Written before Russia invaded Ukraine and began rattling its nuclear sabers, it is a hopeful but not optimistic book. His concluding thought was: “Much of the edifice of arms control has been torn down. It’s up to us to rebuild it. Success is again possible because failure would be too costly.” We believed Michael would be with us to help us think our way through the paths to practical and realistic policy solutions. Our tragedy is that his intellect and experience have now been lost to us.

Michael and I were colleagues going back 40 years to ACDA in the Carter Administration. After he left to co-found the Stimson Center with Barry Blechman, we met periodically to share experiences and perceptions, his from the outside, mine from the inside. Needless to say, we did not always see eye to eye.

Many years thereafter, we reengaged as friends during his research for the book. Principally, he quizzed me on my service as lead Clinton Administration negotiator to revive the 1972 ABM Treaty, following the Star Wars interlude of the Reagan era. The negotiations, lasting six years, resulted in a number of hopeful agreements with Russia and the successor states. But ultimately, the effort failed owing to Clinton’s political weakness and Republican pressures to deploy advanced missile defenses. In 2001, President Bush announced our intention to withdraw from the ABM Treaty.

In a way, the ABM story I shared with him was emblematic of the book’s chronicle of sound but lost arms control causes. He could not understand why we would give up legally binding, verifiable limits on missile defenses in exchange for the technical uncertainties of untried defenses in the midst of war during the last 15 minutes of reentry. We agreed, wouldn’t good policy be served by both capable defenses subject to legal limits?

Michael’s legacy is assured—in his books and articles, in the scholars and civil servants he mentored, and in the Stimson Center itself. We will miss his gentle and impelling voice."Dr. Stanley Riveles, ACDA and Department of State (ret.), U.S. Commissioner, Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, 1993-2000

"The Stimson Center lost its founder, I lost a friend and colleague, and the world lost a tireless proponent of peace and international security. Michael had a following all over the world, including in many countries that I have traveled to. What comes to mind at this sad time are the words of the most revered Kazakh poet, Abai:

“Many people gave their lives to the fleeting world,

Putting their best foot first to the death from the birth,

But is it possible to say, that the man is dead,

If he’s left in the world the immortal word?”

Michael, indeed, left us the immortal word in arms control and nuclear security with his many writings, including his recent capstone book Winning and Losing the Nuclear Peace.

My condolences to Michael's family and friends."Sig Hecker, Center for International Security and Cooperation, Stanford University

"Those of us whose entire careers were with the Government had interactions with a wide cross-section of the NGO community. Standing out were the Stimson Center, and Michael Krepon in particular. When dealing with nuclear nonproliferation and with South Asia, Michael displayed a deep knowledge and an earnest pragmatism that commanded attention.

What Michael sought in multilateral forums dealing with nuclear issues were incremental steps—steps that had some chance of being accepted within the U.S. interagency process and of being acquiesced in by the other nuclear weapons states. He did not shy away from advocating for total nuclear disarmament but he recognized that it could not be achieved without addressing the myriad practical and political hurdles standing in the way.

Michael took a similar approach to nuclear weapons development in South Asia. Not only did he contribute ideas to US Government efforts to limit such development, he also personally planted numerous seeds of peace with individuals from both India and Pakistan. Some of those seeds have borne fruit while others lay dormant awaiting a more favorable environment.

Michael’s ideas, spoken and written, will stand as major contributions to the effort to curb the spread of nuclear weapons."Ambassador Norman A. Wulf (ret.) Special Representative of the President For Nuclear Nonproliferation

"I cannot say how much I learned from Michael. Everything from how to reach out to stakeholders and to always have intellectual curiosity, he demonstrated the way to be a policy experts through his own writing and activities. What he taught me by his actions most was the importance of mentorship to junior scholars and provide them guidance and support for their professional development."

Yuki Tatsumi, Stimson colleague

"I am extremely saddened to hear about the demise of Michael Krepon. He was a mentor of mentors, and a caring friend of mine. We would often have e-mail exchanges discussing the prospects of Nuclear Arms Reduction at the global level, as well as probable solutions to the challenges facing international non-proliferation regimes. We had differing views on most of these issues, but that never crossed our way to maintaining a decent friendship. It's indeed a great loss for the international community of strategists. May he rest in eternal peace!"

Air Commodore (R) Khalid Iqbal

"Michael was a gentle arms control guru who was also a true mensch. He always made time for a conversation and was generous in sharing his views. He was soft-spoken and chose his words with care, but they were all the more wise and impactful for that. He persevered with arms control advocacy even when this was out of fashion and had the inner conviction that a better world was achievable. He saw bright possibilities even in dark times. We kept in touch after I retired from government service and shared enthusiasm for conflict prevention measures, such as a Code of Conduct for Outer Space Security that few paid attention to. He leaves a vast and moving legacy both in his writings and his personal engagement."

Paul Meyer

"My first three articles for the South Asian Voices received a flurry of long comments from Michael Krepon. Those remarks were insightful and encouraging, to say the least. However, what was noticeable and reflective through those was Michael's deep understanding of, and concern about, South Asia's nuclear dynamics. Seeing my interests in reading classics on nuclear strategy, he gifted me Morton Halperin's 'Limited War in the Nuclear Age.' The inscription on the book read : ""Don't try this at home."" In another meeting, he discussed with us all the importance of asking good questions. That, I must stress, was an enriching session. Last but not least, what will stick with me is his telling me this: ""We are not here to tell you what to think; we are just here to help you think."" May God bless his departed soul."

Syed Ali Zia Jaffery

"In recent years, I always sent Michael drafts of my writings on arms control and strategic-nuclear issues. He was always a super sensible sounding board, source of good advice, and encouragement. Plus, his love of his garden, not least his ferns, always provided a source of cheer in complicated times. We shall very much miss both in today's world."

Lewis Dunn

"There was a time when Michael and I were frequently in touch, and especially during the ""Operation Brasstacks"" (1986-87) when the Vajpayee Government in New Delhi took a very aggressive posture towards Pakistan, and Michael was really worried that India and Pakistan were poised for a war with possibly nuclear weapons in the play. In short he was very worried, and it was my job to calm him - he was looking at the situation from a traditional western perspective, and I knew the Indian ""kabuki dance"" on the Rajasthan border would not amount to anything given the character and style of the Indian PM and frailty of the Indian polity at that time. But of course, he felt least assured by my soothing words and undertook a trip to India to assess the situation for himself and met with many Indian military generals, including the DGMO. On his return, he was even more convinced that a war was looming in the subcontinent. So I bet him a lunch at a restaurant of choice if I am proven wrong, and the vice versa. Some time later, when I had forgotten the whole affair, he called me and said, ""I owe you a lunch."" I said to myself what a gentleman and a sweet person. So we had the lunch together., but more importantly, we enjoyed the conversation and his company.

We stayed in touch over the years though Covid took its toll. But I saw him only a few months back. He looked frail but the sparkle in his eyes was as bright as ever. I will surely miss him. Michael was a very passionate man dedicated to peace and stability in South Asia. A true friend of the region where one-sixth of the humanity lives.

I will cherish his books that he autographed me."Vijay Sazawal, Ph.D.

"Michael Krepon was a giant of the field, but more than that, he was a mentor, an ally, and a friend, including to Student Pugwash USA. His legacy will live on in his epic accomplishments and the words of inspiration and guidance he shared with a whole generation of arms control advocates. A few months ago, Michael shared this wisdom in discussion with myself and SPUSA. “We live in dark times. And this isn’t the first time. But… it’s always darkest before the dawn in this field. We’ve got to rebuild. We’ve got to persevere. We’ve got to be creative. We also have to be insistent. But we can do this. I’m proof that persistence matters.” Speaking directly to young people and professionals in the field, he added: “You’re facing tremendous resistance. (But) every good achievement, every great achievement, has occurred against resistance. So find ways to refresh your spirits… you don’t have to look for huge victories. Daily victories matter, and they will accumulate.” Thank you for everything you did, Michael, for the community and for us all as individuals. Rest in peace."

Shane Ward, on behalf of Student Pugwash USA

"Michael was a intellectual giant in the field of arms control and nonproliferation. He earned respect across the political spectrum and inspired generations of younger talent. We may not soon see a worthy successor."

William Courtney

"In Japan and at the United Nations I very much appreciated his advices and insights on world peace and security. His passing comes at a critical time when the world needs his advices more than ever. I send my deepest condolences upon his passing. Nobuyasu Abe, former UN Under-Secretary-General for Disarmament Affairs."

Nobuyasu Abe

"I came across Michael and his work in my capacity as an Indian diplomat. We shared an interest in nuclear security issues and I met him during my visits to Washington and when I was invited to speak at Stimson. I had the privilege of hosting him in Delhi and the presentation he made on nuclear security to a large audience left a deep impression. He will be missed both for his personal qualities as well as one of the foremost scholars on security issues, in particular nuclear security. I convey my sincere condolences to his bereaved family and to Stimson. May his soul rest in peace."

Shyam Saran

"My first meeting with Michael was probably his first visit to India in 1992. He was Invited to address the Fellows and Researchers at the Institute of Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi, that I chaired. He began by reading out from the lead article of the current issue of our monthly journal Strategic Analyses, which I had authored. In it I had narrated my personal view of the collapse of the Soviet Union in Nov 1989, even when it probably had the largest nuclear arsenal and the strongest military. That led to a common bond that has lasted to this day. His support and friendship through subsequent years, shaped my life thereafter. Never forget his quiet and gentle voice, his love and consideration and steadfast interest and guidance."

Maj. Gen. Dipankar Banerjee (Retd)

"Of the many things that Michael taught me over almost forty years of friendship, the most important was to treat everyday as a "bonus day." Thank you, Michael."

Dan Caldwell

"Michael and I met in 1973 or 1974. I worked for Senator Dick Clark of Iowa and Michael was then working either for ACDA or for a House Armed Services Committee member. We bonded over, of course, baseball. We talked hours more baseball than public policy, though we spent a lot of time on both. When Michael asked me to be in his wedding, I surprised and honored. I left Washington in late 1975, but we stayed in touch through the years. My wife and I had lunch with him the summer of 2000. He autographed his last book for me. He sent me an email on May 27 to tell me of the terminal nature of his condition. I am saddened. He left a legacy both professionally and personally. It's a cliche', but he will certainly be missed."

Robert Mulqueen

"Little did I know when I met Michael in 1993 that he would become an important member of our family. What I did not know at the time was that Michael was also mentoring my future wife, Lisa Owens Davis, and that he would be here with us as she lost her battle with cancer a couple of years ago. Yes, he guided our intellectual growth and career choices. I traveled with him to South Asia, where we had tons of fun with our Indian and Pakistani friends. And panels, so many panels. But Michael also ministered to our souls as we faced the ultimate challenge of death. He shared with us his own thoughts about death and dying. He called, he showed up, he listened, he shared, he understood and he cared. Our connection went far beyond national security and arms control. A giant in the field, yes. A force for good and the triumph of our "better angels," without a doubt. He must have set a record for mentoring. But Michael Krepon's influence and goodness far exceeded the material confines of this world and reached the spiritual and mystical realms, where he was also a master teacher and guide. I really loved that guy."

Zachary Davis

"I am so sad to hear of Michael’s passing. I feel very fortunate to have had the opportunity to interview, film and photograph him several times while I was a Communications Specialist at the Stimson Center. I will forever be grateful for the many hours I spent intently listening to him speak, soaking up as much knowledge from him as I could. His legacy will live on forever."

Lillian Mercho, Stimson colleague

"For those of us working the South Asia beat in the late 1990s, especially India and Pakistan, Michael was an invaluable adviser. He was also very patient with us. After hearing us out on what our policy initiatives were (and wanting him to enthusiastically support), he would invariably say: ""Very interesting, but have you ever thought about -----"". And he always said it with a smile.

Our world was a better and safer place with Michael in it. Godspeed Michael."Karl / Rick Inderfurth

"Very sorry to hear about the passing away of a tireless champion of nuclear nonproliferation. His works on South Asia, especially on stability-instability paradox, have been very illuminating."

T.V. Paul

"While I never had the privilege of meeting Mr. Krepon personally, his writing, passion and advocacy for building a world free of nuclear danger inspired my own research into the topic; first as a graduate student and later as a faculty member at the National Defense University. I owe him a debt of gratitude for providing an immeasurable gift of scholarly research and other good works which, hopefully, will change the world for the better."

Darryl Woolfolk

"I had the immense honour of participating and speaking at a virtual launch event of his book “Winning and Losing the Nuclear Peace: The Rise, Demise and Revival of Arms Control” - and it was only a few months ago. Like so many others, I always admired, and was inspired by, his analysis and vision for preventing conflict and making the world a safer and a more secure place. He will be missed so much - but I renew my commitment to this important work, together with so many who have been inspired by him."

Izumi Nakamitsu

"I knew Michael through his texts first. Then I met him through my boss Dr Arbatov and his projects. Finally, I met him personally and was part of Michael's projects, and he participated in the projects I organized. He was, and still is, a role model for me and, I believe, for many coming to our research area. When I reached him at a conference somewhere many years ago for the first time, who was I? My English was poor. Still, he stopped; he was attentive and behaved like an equal to me. And it was always Michael's approach to younger scholars. The last time he contacted me suggested making a launching discussion of his book in Sweden, "Winning and Losing the Nuclear Peace". Unfortunately, it was time when I was relocating from Sweden to Russia. I was so sorry not to be able to arrange this discussion at that time. However, I firmly believe that this book is a sound message from Michael that we must listen to "for the revival of arms control."

Petr Topychkanov

"Michael brought me to the Stimson Center to launch the Japan Program and support work on Confidence-Building Measures especially between Japan and China. His vision and commitment to paving the way to peace one stone at a time remains the guiding principle for all my work. He would tell me to focus on the details and be sure to get them right — because the tiniest things matter and you need credibility above all else. Then he would remind me to raise my gaze and recall the fundamental purpose of the work I was doing. In Tokyo one time he grew frustrated with how tentative I was in relations with Japanese bureaucrats, and finally we had an argument in which I told him he was misunderstanding how to exert influence in the cultural and political context I had studied for over a decade. He laughed and said he was grateful to clear the air and once I spelled out why our theory of impact had to be longer-term he embraced that and afterwards he always defended me. Michael was always at least one step ahead in his thinking, and always passionate about the long-term goal. May his memory be for a blessing."

Ben Self, Stimson colleague

"Michael was a great scholar, a tireless activist for peace, an inspiring educator, and a wonderful man. This world needs a thousand Michaels, but there will be only one. There is a big hole in our universe. My thoughts and prayers for his family and his friends."

Joseph Collins

"Michael made so many contributions, but his emphasis on the importance and practice of "restraint" in strategic matters--whether nuclear or space--will, I. think, remain especially influential as policymakers imagine how to cope with a wave of new challenges. He was a model of thoughtfulness, demonstrating that bluster was not a necessary component of being influential, and generous and reassuring to younger people coming into the field, including, at one time, this one."

Chris Chyba

"He was welcoming and a quiet guide by his words and actions. I learned to follow his lead and benefit from his deep knowledge and passion for peace."

Shuja Nawaz

"Michael has a unique way of seeing people and building their confidence. He brings a sense of mission to the people working with or around him. He is always eager to hear what younger scholars have to say and sees the value in what others might consider untraditional analysis. For us younger scholars, who are usually awed and daunted by the depth of the knowledge from veterans like Michael, his encouragement comes not only as a push of support, but also as a sense of mandate by responsibility."

Yun Sun, Stimson colleague

"It is hard to overstate the impact Michael Krepon has had on a whole generation of nuclear scholars — particularly those, like me, who came of age with India and Pakistan’s 1998 nuclear tests and the birth of a delicate nuclear subsystem in Southern Asia that few in the United States were equipped to understand, let alone manage."

Vipin Narang

"Michael Krepon’s contribution to preventing nuclear conflict is immense and legendary. So too are his contributions to offering a vision, building community, and inspiring others to join the effort to prevent conflicts. I know because I have experienced and seen his impact for more than 30 years. And my hunch is that there are hundreds of people like me who are deeply affected by all he has offered."

Victoria Holt, Stimson colleague

"As one of the original Stimson board members, I was present at the creation and retain indelible memories of Michael’s entrepreneurial vision, unwavering persistence and genuine commitment to furthering the Stimson mission. Along with Barry, he played an indispensable role in building and sustaining the institution. All this, of course, in addition to his own prolific research and writing that have influenced so many policy makers and thought leaders over these many years. Michael’s legacy is timeless, and he is owed an incalculable debt of gratitude."

Roger Leeds, former Stimson Board Member

Please consider a special donation to the Stimson Center in honor of Michael Krepon

To donate via wire or ACH, please contact Tia Jeffress. Or mail a check made out to The Henry L. Stimson Center to 1211 Connecticut Avenue, NW Suite 800, Washington, DC 20036.