Introduction

At the Warsaw Summit in 2016, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) adopted its first-ever Protection of Civilians (PoC) policy. Developed partly in response to mounting criticism against the Alliance’s history of causing civilian casualties during its operations in Libya and Afghanistan, the policy reinforced NATO’s commitment to more effective civilian harm mitigation. It also articulated a level of ambition to protect civilians from violence by third parties. As a result, NATO has tried to develop a comprehensive framework dedicated to PoC, with the ultimate goal to not only ‘minimize and mitigate the negative effects that might arise from NATO and NATO-led military operations’ but also to ‘protect civilians from conflict-related physical violence or threats of physical violence by other actors, including through the establishment of a safe and secure environment’ (emphasis added).1 Note: NATO, ‘NATO Policy for the Protection of Civilians Endorsed by the Heads of State and Government Participating in the Meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Warsaw’, NATO, 9 July 2016, para. 9, http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_133945.htm. This aspect brought its protection of civilians approach more in line with the United Nations’ proactive understanding of PoC. Indeed, during the development phase of NATO’s PoC policy, NATO officials extensively consulted with UN PoC officials and experts.2 Note: Joachim A. Koops and Christian Patz, ‘UN, EU, and NATO Approaches to the Protection of Civilians: Policies, Implementation, and Comparative Advantages’ (International Peace Institute, 10 March 2022), 5, https://www.ipinst.org/2022/03/un-eu-and-nato-approaches-to-the-protection-of-civilians. However, NATO could also draw on its previous experiences, lessons identified, and doctrines related to its peace support operations during the 1990s in the Balkans.3 Note: Koops and Patz, ‘UN, EU, and NATO Approaches to the Protection of Civilians’, 4. Furthermore, since 2010, when NATO created a small PoC cell in the Operations Division at its Brussels headquarters, a small unit (now under the Human Security umbrella) has been advancing PoC policy and innovations.4 Note: Kathleen H. Dock, ‘Origins, Progress, and Unfinished Business: NATO’s Protection of Civilians Policy’ (Washington, DC: The Stimson Center, 18 March 2021), 5, https://www.stimson.org/2021/origins-progress-and-unfinished-business-natos-protection-of-civilians-policy/.

Following the North Atlantic Council’s adoption of NATO’s official policy, the Military Committee developed a PoC Military Concept in 2018, followed by the publication of a comprehensive Protection of Civilians Handbook by the Allied Command Operations (ACO) in 2021.5 Note: ‘Protection of Civilians ACO Handbook’ (NATO, 11 March 2021), https://shape.nato.int/resources/3/website/ACO-Protection-of-Civilians-Handbook.pdf. At the Madrid Summit in June 2022, NATO’s Heads of State and Government reinforced the ‘centrality’ of NATO’s new Human Security approach. NATO’s new Strategic Concept clarifies that the protection of civilians is part of Human Security and is ‘essential to our approach to crisis prevention and management’.6 Note: NATO, ‘Madrid Summit Declaration Issued by NATO Heads of State and Government (2022)’, NATO, n.d., para. 13, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_196951.htm; ‘NATO 2022 Strategic Concept’ (NATO, 29 June 2022), para. 39, https://www.nato.int/strategic-concept/. Thus, during the last six years, NATO has significantly elevated and advanced the development of its PoC policies and frameworks, enshrining them at the highest political and strategic level. This work is critical considering the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The sheer scale of ongoing attacks on civilians and civilian infrastructure has reinforced the significance and urgency of PoC capabilities in an entirely new context of urban warfare waged by an external force against one of NATO’s strategic partners.7 Note: Dr. David Kilcullen and Gordon Pendleton, ‘Future Urban Conflict, Technology, and the Protection of Civilians’ (Washington, DC: The Stimson Center, 10 June 2021), https://www.stimson.org/2021/future-urban-conflict-technology-and-the-protection-of-civilians/.

While NATO has made significant progress in developing PoC policies, guidance and the Human Security approach, it is less clear how prepared the Alliance is to implement and mobilize its PoC approach in a future crisis. In this context, conducting an organization-wide ‘PoC preparedness assessment’ or ‘PoC audit’ could help determine NATO’s preparedness for implementing PoC. Such a study would need to consider core elements at the organizational level of NATO itself (e.g., policies and guidance, best practices, training and education, and planning) but also at the national level, as all crucial implementation capacities are in the hands of Allies rather than NATO’s institutional structures. Thus, an assessment or audit needs to consider both levels and their interplay.

For example, when it comes to NATO doctrine and policy guidelines, they are influenced by national policymakers and directly affect national policy-making processes. In Germany, for example, many NATO doctrines have ‘direct effect’, i.e., they are directly translated into national doctrines for the German Armed Forces. In addition, NATO’s PoC policies did not emerge from a vacuum but alongside active exchanges with other international organizations (particularly the United Nations, despite the different mission sets of the two organizations). A comprehensive PoC audit would thus take these aspects into account.

Currently, no agreed-upon methodology or framework for a PoC audit or assessment has been developed. However, there are precedents from Allies related to PoC evaluations that NATO could build on. The authors of this report conducted one such assessment for the German Ministry of Defense between 2019 and 2021. The advisory project, ‘Implementing the Protection of Civilians Concept in United Nations Peace Operations’ (hereafter referred to as the ‘Implementing PoC’ project), was requested and financed by the German Ministry of Defense to gain a comprehensive overview of Germany’s PoC preparedness in the context of the United Nations. However, it also took into consideration the context of NATO, the EU, and other national experiences. A core aspect of the project was the development of an evaluation framework for conducting a systematic audit and gap analysis of Germany’s PoC capabilities and preparedness.8 Note: The 440 pages report and detailed gap analysis is not public, but a shortened executive version is due to be released in early 2023. For more information on the project, visit https://www.implementing-poc.com/ The project’s explicit aim was to develop an audit framework that could be used and adapted by other nations and in different organizational contexts.

While the final report is not yet in the public domain, an executive summary and core findings will be released in 2023. As co-authors of the German PoC report, we can, for this Stimson Policy Paper Series, draw on the general analysis framework developed for Germany’s PoC evaluation and outline how it could serve as a basis for a possible NATO PoC preparedness analysis. The approach developed in the German case included not only an assessment of material capabilities, operational experiences, and resources of the German Armed Forces, but it also assessed the interplay between military and non-military tools (and ministries responsible for promoting these tools) and examined doctrine, guideline, and PoC-relevant approaches to training. A PoC preparedness assessment and audit for NATO could follow similar approaches to provide NATO planners and NATO Allies with a more complete picture of the gaps and opportunities for moving from PoC policy to implementation.

The following section outlines the main building blocks for a PoC preparedness assessment. We draw on the German UN PoC study and highlight how the analysis can be applied to NATO’s PoC preparedness. We will clarify what PoC preparedness means and explain the core elements related to the concept. After that, we will discuss the methodology developed in conducting a gap analysis and national audit of Germany’s PoC preparedness and the extent to which it can be applied in a NATO PoC assessment. In the following section, we will outline findings related to the case of Germany’s PoC assessment, particularly concerning NATO. While we cannot go into the details of the report’s results and the PoC gap analysis itself, we can refer to some general observations that we were permitted to share in open workshops related to the interplay of NATO and German PoC aspects.9 Note: See, e.g., the presentation by Joachim A. Koops and Christian Patz, ‘Lessons Learned on PoC Experiences from Germany’, in PAX Protection of Civilians Conference 2020, n.d., https://protectionofcivilians.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Program-PAX-PoC-Conference-2020.pdf. In the concluding section, we offer some reflections on the initial lessons and opportunities a NATO PoC preparedness audit would offer.

Core Elements of a PoC Preparedness Assessment

There is no official definition or conceptualization of ‘PoC preparedness’. We define PoC preparedness as the sum of core resources, mindset, capabilities, guidelines, experiences, processes, and enabling elements required to effectively operationalize and implement the protection of civilians policy at the strategic, operational, and tactical levels. Preparedness requires well-trained human resources (whether military or civilian) and long-term investments in material resources and core military capabilities for conducting a wide range of PoC tasks in the field (related to strategic enablers). In addition, PoC preparedness requires continuous education, training, and exercising at strategic, operational, and tactical levels. It requires well-functioning and institutionalized lessons-learned processes, identifying best practices and feedback cycles where new insights lead to updated training materials. PoC preparedness also includes good planning capacities, operational experiences of key personnel, and well-adjusted doctrines and guidelines. Finally, a well-prepared PoC organization uses partnerships with other core PoC actors (such as the UN, EU, African Union, or other national PoC players) and can apply a minimum degree of a comprehensive approach to different levels (i.e., within the organization, across ministries) to avoid direct competition or friction.

In the context of NATO, a professional and effective CIMIC (Civil-Military Cooperation) approach involving other external actors in the field or theatre of operation also aids effective PoC implementation, but is insufficient to accomplish adequate protection. At the strategic level, PoC tools and approaches by the military and civilians should be accompanied by, and ideally embedded in, a broader political strategy toward the conflict zone and neighboring countries, powers, or potential spoilers. Finally, and often as a combination of education, training, operational experiences, and the internalization of guidelines, a ‘PoC mindset’ should be explicitly aimed for and institutionalized at every level of the organization. Indeed, UN and NATO documents and leaders have frequently stressed this aspect in PoC implementation discussions. NATO’s PoC handbook stresses the ‘necessity to attain a Protection of Civilians (PoC) mindset’.10 Note: ‘Protection of Civilians ACO Handbook’, 7. This is also closely linked to the importance of leadership in advancing, monitoring, and insisting on an active PoC mindset at all levels of the organization, from the highest political level to the individual on the ground.

Table 1 provides a summary and overview of the core elements of PoC preparedness and some indicators.

Table 1: Core Elements of PoC Preparedness

| PoC Preparedness Elements | Description | Indicators |

| Human Resources | The quantity and quality of military and civilian personnel with relevant PoC experience and expertise (ranging from combat experience to extensive CIMIC experience, women, peace and security experience, including female personnel, intercultural experience, language skills, threat assessment and analysis skills, mediation and conflict resolution skills, in-depth knowledge of PoC policies | Quantitative indicators: training completion indicators, written and practical exams on PoC-relevant skills, qualitative questionnaires, interviews, and operational observations of PoC knowledge and PoC mindset (by, e.g., lessons learned teams) |

| PoC Mindset | Senior leadership with a clear understanding of the strategic, operational, and tactical importance of PoC; prioritization of PoC at all levels of the organization; willingness and ability to implement PoC beyond basic IHL or harm mitigation approach | After Action Reviews focusing on PoC implementation; test and interview scores, policies, training material and doctrines, and guidelines and their focus on building a PoC mindset |

| Financial and Material Resources | Quantity and quality of appropriate resources for comprehensive PoC tasks (including high-value military assets, such as intelligence capabilities, UAVs and reconnaissance capabilities, armed helicopters, tactical air transport, and MEDEVAC capabilities), force protection, etc. | Annual financial reviews, gap analyses of capabilities and capacities should also include PoC-dedicated resources |

| Operational Experiences | Practical experiences with PoC implementation at the organizational, national, and individual levels (strategic, operational, and tactical) because of previous deployments with PoC tasks | Quantitative measure of missions and operations with PoC tasks; After Action Reviews |

| Lessons Identified, Lessons Learned, and Best Practices | Systematic and institutionalized processes and dedicated personnel for identifying lessons from PoC tasks and operations and improvement actions towards lessons learned and identification of best practices (both at organizational, national, and inter-organizational levels, i.e., exchanges of lessons learned and best practices with other PoC actors) | Lessons Learned indicators, reports, implementation cycles, quantitative indicators of personnel and units dedicated to PoC, review of best practices and reviews of implementation; meetings with other PoC actors solely dedicated to exchanging LLs and best practices |

| Doctrines and Guidelines | The quality, up-to-dateness, ‘usability’ dissemination, and ‘acceptance’ of doctrines and guidelines across the organization dealing with PoC | Inventory of PoC guidelines and doctrines (or PoC-relevant passages in doctrine documents) and periodic review of their up-to-dateness and knowledge of the guidelines across the organization |

| Planning Capacities | Quantity and quality of planning capacities and processes related to PoC tasks, PoC threat assessments, and tailor-made scenarios | Quantitative and qualitative evaluation |

| Education, Training and Exercises | Quality of PoC-specific training, exercises, and education and the quantity and quality of training participants; wide range of PoC training at strategic, operational, and tactical levels; training both NATO-specific as well as training in cooperation with other PoC actors | Quality of PoC-specific training (rather than generic peace support / IHL training); head count of graduates from PoC training, education, and exercises |

| Support for broader political initiatives | PoC capabilities and preparedness is embedded and closely linked to broader political initiatives for addressing major conflict zones and protection approaches | Existence and impact of political initiatives and coherence with/link to PoC approaches |

| Comprehensive Approach (organization and national level) | PoC tools are developed in the spirit of a ‘comprehensive approach’—connecting military and civilian tools across the organization and the national level (i.e., ministries of defense, foreign affairs, interior, etc.) | Level of comprehensive planning and implementation, coordination, and exchanges |

| CIMIC/International Partnerships | Cooperation and coordination with crucial PoC actors at strategic/political, operational, and tactical levels—in capitals and the field; ideally, mutual reinforcement with other PoC actors; frequent inter-organizational exchanges | CIMIC evaluation, inter-organizational partnership evaluations |

These 11 elements provide different aspects for a multilateral organization or state to reinforce its PoC preparedness and increase its capacity for effective PoC implementation. For a state or organization to successfully implement PoC, processes and resources must be freed and applied at the organizational and national levels across strategic, operational, and tactical domains.

The section below will outline the main parts of the methodology related to the PoC capability and preparedness of Germany.

Methodology for Evaluating Germany’s PoC Capabilities and Preparedness

One of the Implementing PoC project’s main objectives was to develop a methodology and analytical framework for assessing a country’s PoC capabilities and PoC preparedness. We used this methodology to establish an initial ‘PoC inventory’ and ‘baseline’ (i.e., what are the core minimum and core ‘ideal’ requirements and dimensions of PoC at the strategic, operational and tactical levels) followed by an in-depth ‘gap Analysis’ of core PoC tasks and abilities.

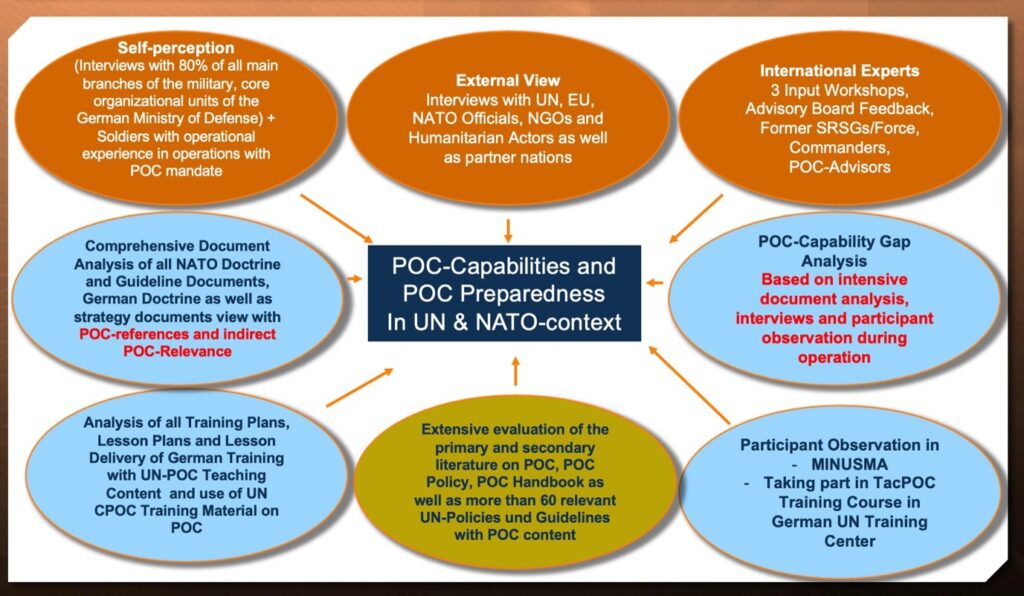

To identify the PoC tasks and capabilities required for Germany in the UN context, a comprehensive analysis of all UN documents, policies, training materials, and the UN handbook was conducted. The team identified 744 tasks for PoC implementation at the operational, strategic, and tactical levels. Tasks were then systematically assessed using extensive interviews, document and doctrine analysis, participant observation, and external input. Figure 1 below summarizes the main steps developed and conducted as part of the methodology and data gathering for the PoC assessment and eventual gap analysis.

While the main focus of the data gathering and analysis during the German PoC assessment initially looked at how well Germany complied with the requirements and standards of the UN’s PoC Policy, it soon became apparent that this approach was too narrow and did not capture the influence of NATO and the EU on Germany’s PoC approach. Therefore, the decision was taken to capture the entire spectrum of Germany’s PoC-experiences in the context of other organizations and concerning participation in NATO and EU operations. This also required adapting the basic methodology and scope of the study, underlining that to truly capture a country’s approach to PoC and PoC readiness, the interplay between different organizational requirements and contexts needs to be captured. We, therefore, also assessed policy developments and operational experiences within the EU’s Common Security and Defense Policy (particularly Germany’s operational lead of the EUFOR RD Congo mission in 2006) as contributing to the overall set of PoC experiences. The methodology included interviews and document analyses that considered how PoC experiences in the NATO and EU contexts contributed to Germany’s understanding of and preparation for PoC implementation. It is worth noting that the EU has also been developing its own PoC policies and approaches, but they have received less attention and prominence in national and international discussions on the subject.11 Note: For an in-depth analysis of EU approaches to PoC and its relationship with NATO and UN PoC Approaches, see Koops and Patz, ‘UN, EU, and NATO Approaches to the Protection of Civilians’.

We conducted interviews with a cross-section of representatives of all branches of the German military (ranging from junior staff to senior officers and generals), senior policy officers of the Ministry of Defense, and related German ministries (such as the Foreign Office and Ministry of Interior). The interviews were based on a standardized questionnaire with questions related to knowledge and interpretation of PoC policies, PoC experiences, and views on the strengths and weaknesses of Germany’s PoC implementation. These questionnaires also sought to establish the extent to which a ‘PoC mindset’ was present or in the process of forming across different branches.

In addition, the team interviewed external experts and officials from the UN, NATO, the EU, and other partner nations with PoC expertise to gain an exterior view and expert assessment of Germany’s performance in PoC. We organized three expert workshops (two in the US and one large one in Germany), bringing together junior, senior, and mid-level officials, soldiers that served in PoC-focused operations, and core PoC experts from the UN, NATO, and EU national experts. We conducted extensive focus group discussions with a wide range of UN Force Commanders and solicited input from an external international advisory board (consisting of former UN Special Representatives of the Secretary-General in UN operations with a strong PoC focus, US, French and Canadian government officials with vast experience in the drafting of PoC policies and their implementation, think tank researchers and peace operation experts). These consultations gave the team additional insights and helped answer questions from the initial extensive desk research and document analyses.

Furthermore, we gathered information and impressions through active ‘participant observation’. Members of the writing team participated in Germany’s first pilot PoC training course at the tactical level, organized in 2019. They served as civilian liaison officers in the German contingent in the UN Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA). These practical experiences allowed for further ‘reality checks’ and additional data gathering.

The team analyzed all available training courses in Germany related to peace operations, military crisis management, and international military missions to assess the content of PoC-related tasks, policies, and required expertise. A comparative analysis was conducted with the content and lessons planned for existing training in Germany and the PoC training material of the United Nations. In addition, a systematic analysis of other international PoC-related trainings was carried out (e.g., a mapping of over 40 training courses across the globe on peace operations and PoC, including the NATO-UN PoC training offered by the Finnish Defense Forces International Centre), which provided information for formulating a baseline and ‘ideal-type’ training used for evaluating training content offered by Germany.

A large part of the methodology related to extensive national doctrine analysis as we sought to identify how much PoC content and guidance is ‘on the books’. We assessed German doctrine documents, comparing them with those available from the UN, EU, and NATO doctrine and policy documents. As a first step in the mapping, we examined the core doctrinal guidelines and documents on the command and training of forces to collect empirical data on their relation and relevance to PoC in three steps. The potential PoC-relevance of German/NATO regulations was determined based on the review and analysis of the title, table of contents, and outline of the respective documents. In this pre-selection process, we digitally reviewed all current Bundeswehr regulations through the German Ministry’s intranet.

In the third analysis step, we identified the paragraphs of the 2019 UN PoC Policy and the NATO PoC Military Concept related to military activities relevant to PoC. We compared them to the core doctrinal guidelines and documents of the command and training of forces in the Bundeswehr, which the authors identified and found to be potentially relevant and applicable to PoC. For this purpose, the analysis differentiated the UN PoC policy according to its three tiers—Tier I: Dialogue and Engagement, Tier II: Physical Protection, Tier III: Establishment of a Protective Environment—and NATO’s PoC Military Concept according to its four elements: Understanding the Human Environment (UHE), Mitigate Harm (MH), Facilitate Access to Basic Needs (FABN), and Contribute to a Safe and Secure Environment (C-SASE).

The document analysis revealed the degree to which the Bundeswehr’s core doctrinal guidelines and documents are PoC-related and PoC-relevant and to what degree they match the core requirements of the UN’s PoC approaches. Since most of Germany’s military doctrines are a direct adoption of NATO policies, guidelines, and doctrine, the document analysis also provided a systematic analysis of German and relevant NATO doctrines to assess the extent to which they contained PoC provisions or PoC-relevant aspects that were already in the German national doctrinal domain. The analysis aimed to answer whether PoC is an entirely new task requiring a new separate doctrine document or whether there are sufficient elements related to PoC tasks already in the doctrine domain.

Out of 4,524 paragraphs of NATO and German Armed Forces doctrines, 2,162 (or 48 per cent) were ‘directly relevant’ to the core tasks outlined in the UN PoC Policy and NATO PoC Policy. By ‘directly relevant’, we mean that the tasks or guidelines were very close to or, in some instances, identical to UN and NATO PoC provisions. The analysis revealed that even preceding the 2016 NATO PoC policy, many NATO doctrine documents already had relevant passages for PoC tasks and were thus directly applicable to the German doctrinal landscape.

Unsurprisingly, the highest number of paragraphs relevant to the protection of civilians was found in documents dealing with stabilization and counterinsurgency, policing and security force assistance, as well as aspects relating to humanitarian assistance operations, together making up the group of highly PoC-relevant documents (90 per cent or above). Among the NATO documents, the doctrine documents with the highest number of PoC relevant paragraphs are the Allied Joint Doctrines for Military Police (AJP-3.2.3.3) with 92 per cent and Stability Policing (AJP-3.22) with 97 per cent, the Allied Joint Doctrines for the Military Contribution to Stabilization and Reconstruction (AJP-3.4.5-A1) with 94 per cent, Military Contribution to Humanitarian Assistance (AJP-3.4.3) with 96 per cent and Non-combatant Evacuation Operations (AJP-3.4.2) with 94 per cent as well as Security Force Assistance (SFA) (AJP-3.16) with 97 per cent. Almost all the tasks outlined in these existing doctrinal documents were similar to the tasks and approaches outlined in the NATO and PoC Policy. This, of course, highlights not only the cross-fertilization nature of doctrinal writing (often the result of informal and formal exchanges among Allies and between organizations) but also underlines that NATO’s own PoC Policy did not emerge in a vacuum or was formulated from scratch, but rather was based on existing practice related to PoC tasks (even though they were not explicitly labelled as PoC before the 2016 policy). Thus, a considerable body of PoC-relevant tasks and guidelines were already on the books within NATO and in the German doctrinal domain.

Another important document relevant to tasks related to the protection of civilians is the Allied Joint Doctrine for the Military Contribution to Peace Support (AJP-3.4.1)

The doctrinal analysis revealed that although NATO did not develop an official PoC policy before 2016, the Alliance had already been engaged in PoC, particularly through its efforts to create ‘a safe and secure environment’ (SASE), harm mitigation, and even the protection of human rights. These tasks have featured in major operations since Bosnia and made their way into official doctrine, most notably the 2001 doctrine on Peace Support Operations and the 2015 Allied Joint Doctrine on Stabilization and Reconstruction.12 Note: ‘Peace Support Operations AJP-3.4.1’ (NATO Standardization Office, July 2001), https://info.publicintelligence.net/NATO-PeaceSupport.pdf.

For future studies, the German study recommended systematically exploring the commonalities and differences between NATO’s doctrines related to ‘creating a safe and secure environment’ on the one hand and the PoC Policy on the other.

Finally, based on the collection of data and based on the 744 identified PoC tasks, a gap analysis framework was developed (including a traffic light system) for assessing comprehensively the extent to which the German Armed Forces and related German ministries are ‘PoC-prepared’, i.e., able to fully meet the PoC requirements, partially fulfil them or not yet meeting them. The gap analysis then provided an overarching picture of the percentage of PoC tasks for which Germany was prepared and which areas required further investments and attention. In the following section below, we outline some core aspects related to the German case study.

Case Study: Germany’s PoC Preparedness at the Strategic, Operational, and Tactical Levels

Germany’s effort to understand its PoC preparedness represents a special case among NATO countries for several reasons. First, it is one of the few known attempts by a NATO member to assess comprehensively its general PoC preparedness. Secondly, the assessment was initiated by the country’s Federal Ministry of Defence primarily to evaluate the military’s capabilities and preparedness, from the political-strategic level to the tactical level, keeping the Vernetzter Ansatz (comprehensive approach) in mind. Third, while the primary focus was on UN-led peace operations, as we described above, the study’s scope extended beyond UN operations to include NATO and EU approaches, concepts, and experiences.

The case of Germany highlights the challenges and potential of assessing the country’s PoC preparedness and delivers valuable lessons and guidance for other Allies’ and partners’ efforts to conduct their assessments. Without going into detail on the yet-unpublished results of Germany’s PoC-preparedness assessment effort, some insights gained during this exercise are relevant for NATO Allies and partners when conducting such an analysis.

The PoC Concept Requires More Socialisation Before the Establishment of a PoC Mindset

In the case of Germany, diverging perceptions and differing conceptual knowledge of PoC sometimes led to confusion among military leaders and decision-makers about the nature of PoC. PoC can become conflated or equated with basic obligations under International Humanitarian Law and operational considerations to avoid and minimize civilian casualties as part of harm mitigation measures during NATO military operations. Also, PoC was often not understood as a stand-alone concept or comprehensive approach but as one of many elements of Peace Support Operations, population-centric Counterinsurgency (COIN), or military-led Stabilization. Recognition of the role of PoC in NATO Article 5 scenarios was also not always apparent. The comprehensive and integrated nature of implementing NATO’s PoC approach demands a high degree of inter-ministerial, civil-military cooperation and a delicate balance between short and long-term perspectives on NATO Allies’ and partners’ engagement. Common to these interpretations was the characterization of PoC as a means to an end, not an end in itself, highlighting the need to clarify the core tasks of militaries under such a mandate.

The Need for Differentiated Analyses

Compared to other organizations aiming to mainstream their PoC approach, NATO’s general advantage lies in its ability to directly feed policy changes and innovations into its member states’ and partners’ military doctrines. Nevertheless, its efforts at becoming a PoC-prepared alliance still depend on the steps member states and partners take toward the effective implementation and operationalization of the approach. Thus, efforts to assess PoC preparedness at the national level are part of a comprehensive understanding of the Alliance’s PoC preparedness, where policies and approaches at the organizational and national levels reinforce each other. As mentioned above, these are best analyzed by disaggregating the various levels of the military hierarchy to account for divergences and differences between the political-strategic, operational, and tactical levels.

Fitting the Existing Doctrinal Pieces to the PoC Preparedness Puzzle

The analysis of key NATO doctrine documents has revealed that many NATO Allied Joint Publications (AJPs) contain PoC-related aspects, tools, or even direct references to protecting civilians. 13 Note: The study analysed 20 selected NATO Allied Joined Publications (AJPs) and German Military doctrine and guideline documents, containing more than 4524 separate paragraphs. When differentiated according to the four different elements of NATO’s PoC approach, it is the Understanding of the Human Environment (UHE) followed by the Contribution to a Safe and Secure Environment (C-SASE) and Mitigating Harm (MH) that are most commonly reflected in NATO’s current doctrinal landscape.14 Note: The study found over 1,470 PoC-relevant paragraphs related to UHE, 876 paragraphs relating to C-SASE as well as 748 and 659 relating to MH and FABN, respectively. As mentioned above, AJPs dedicated to tasks that require a more population-centric view, including Stability Policing, Stabilization and Reconstruction, Humanitarian Assistance, Evacuation Operations, Military Police, Security Force Assistance, and Human Intelligence are scoring the highest in terms of PoC-relevance.15 Note: ‘Allied Joint Doctrine for Counterinsurgency (COIN) AJP-3.4.4 Edition A-1’ (NATO Standardization Office, February 2011), https://info.publicintelligence.net/NATO-Counterinsurgency.pdf; ‘Allied Joint Doctrine for Security Force Assistance AJP-3.16 Edition A-1’ (NATO Standardization Office, 14 August 2017), https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/allied-joint-doctrine-for-security-force-assistance-sfa-ajp-316a; ‘Allied Joint Doctrine for Stability Policing AJP-3.22 Edition A-1’ (NATO Standardization Office, July 2016), https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/628228/20160801-nato_stab_pol_ajp_3_22_a_secured.pdf; ‘Allied Joint Doctrine for Non-Combatant Evacuation Operations. AJP-3.4.2 Edition A’ (NATO Standardization Office, May 2013), https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/625781/doctrine_nato_noncombatant_evacuation_ajp_3_4_2.pdf; ‘Allied Joint Doctrine for Military Police AJP-3.2.3.3’ (NATO Standardization Office, 2009).

These results indicate excellent potential for PoC mainstreaming throughout various NATO doctrine documents, even without a NATO decision to develop a stand-alone AJP dedicated specifically to PoC.

Although many of the pieces of the PoC puzzle are available now, the development of a PoC mindset remains a crucial requirement to make PoC ‘an integral part of all crises and conflict, even when a NATO mission does not have an explicit PoC mandate provided by the NAC that encompasses all aspects of the PoC concept’.16 Note: ‘Protection of Civilians ACO Handbook’, 11.

On the political-strategic level, NATO’s PoC agenda and NATO PoC initiatives (related to the advancement of the PoC policy, training offerings, or keeping it as an important strategic priority in political discussions) have thus far primarily been driven by smaller Allies and partners such as Austria, Finland, or Canada. Germany, in contrast, has not positioned itself as a leader of PoC within NATO. However, its political weight in the Alliance and its strong role in other international fora would place it in an ideal position to play a more active role as ‘PoC-champion’ to further mainstream the concept, particularly against the backdrop of current and future challenges of protecting civilians in scenarios of hybrid and cyber warfare. To be credible in this role, Germany needs to increase its PoC preparedness and re-invest in its role as a credible geopolitical security actor.

At the operational level, Germany’s PoC preparedness depends on the knowledge, ‘mindset’, and leadership of senior personnel across the armed forces and relevant ministries. Even as military leaders, decision-makers, and their civilian counterparts at the operational level are responsible for issuing clear instructions and guidance to the tactical level, they also determine how PoC will be operationalized ‘on the ground’ and received by those to be protected. PoC-knowledge and comprehension by operational-level decision-makers are thus vital for PoC to function at the tactical level. The gap analysis revealed a high commitment to the general principles of IHL and some awareness of PoC as a newly emerging policy field.

At the tactical level,NATO Allies’ and partners’PoC preparedness can be expected to be higher even without dedicated efforts to implement an Alliance PoC policy for two reasons: First, the differences between NATO’s concept of PoC and other organizations’ understanding at the tactical level are not a major problem, as critical PoC-tasks often require the application of the same military skillset—whether in the context of UN, NATO or EU operations. Second, many NATO members states’ and partners’ armed forces can rely on training and exercises conducted according to NATO standards as the basis for implementing PoC on the tactical level. The experiences gathered from decades of stabilization, peace (support) operations and civil-military cooperation build around the comprehensive approach under the banner of other organizations such as the EU. The UN has also exposed NATO militaries to a broad set of scenarios involving the protection of civilians. While there is ample research highlighting the influence NATO militaries have on the culture and conduct of other organizations, the case study of Germany’s PoC preparedness found evidence that the inverse is also true: Soldiers with PoC experience in UN-led peace operations can directly benefit from these when conducting PoC in NATO-led operations. There was one key exception, however: The importance accorded to dialogue and engagement—or Tier 1 in the UN PoC policy’s parlance—is not something that NATO’s existing PoC approach currently reflects. Finally, despite some countries’ emphasis on CIMIC, NATO lacks relevant capabilities in community engagement comparable to those at the level of the UN peacekeeping system. It should also be noted, however, that despite the similarities at the tactical level mentioned above, key differences in approaches between international organizations persist. The UN approach puts a much more differentiated skill set at the center of its PoC implementation, including a wide range of civilian tasks.

On the other hand, NATO’s approach still more strongly emphasizes the military approach. The EU stands midway between the UN and NATO approach. Implementing a military-specific or civilian-led PoC approach differs not only in relation to the organizational context but, of course, also in relation to the type of conflict situation on the ground.

Training, Capacity-Building, and Implementation Partnerships

Dedicated PoC training represents a key component of PoC preparedness, a vital tool for maintaining and advancing basic and specialized skill sets, and a proactive mindset essential for PoC preparedness.

Furthermore, to achieve the desired PoC mindset outlined in NATO’s PoC policy and handbook, the mainstreaming of PoC across the relevant NATO training guidelines would mean that PoC-critical areas such as intelligence, operational planning, strategic communications, and military policing should not only include explicit references to the concept of PoC but also highlight how these core military capabilities are to be employed for protecting civilians. This also means that PoC-specific training content and corresponding exercises should be featured across all levels of the military hierarchy, ranging from courses to military leadership decision-makers in military academies, general staff courses, and senior leadership courses down to the tactical level. Germany has invested considerable resources in developing a comprehensive PoC Training Course at the tactical level—the only comprehensive course at the tactical level based on large-scale scenario-based learning among NATO Allies at the time of this writing.17 Note: Austria has also developed a training course on PoC at the tactical level, but with less emphasis on scenario-based learning Austria has also been piloting its own PoC training at the tactical level, however, Germany’s PoC Training course focuses on UN approaches to PoC rather than on NATO approaches, even though this could be easily adapted. Bringing together NATO and UN (as well as EU) approaches under one training, while highlighting organizational differences in their approaches to PoC, and cooperating with different Allies would increase synergies and general inter-organizational and intra-Alliance awareness and preparedness.

Noting that other organizations are already involved—and sometimes ahead—in PoC-training, it would make sense for NATO to explore further synergies and partnerships for PoC capacity-building. For example, two training courses already advance UN-NATO and UN-EU perspectives on PoC in Europe. The NATO-UN PoC course at the Finnish Defense Forces International Centre (FINCENT) and the European Security and Defense College (ESDC) course on Comprehensive Protection of Civilians (CPoC) highlights opportunities for NATO members’ civilian and military personnel to benefit from other organizations’ approaches and experiences. Furthermore, virtual and online-based courses and modules, such as the online course offered by the Norwegian Defense International Centre (NODEFIC) and NATO’s own virtual reality PoC course, are available.18 Note: ‘Human Security and the Military Role’, Norwegian Armed Forces, n.d., https://www.forsvaret.no/en/courses-and-education/human-security-and-the-military-role; NATO Virtual Reality PoC Course, n.d., https://review.c2ti.com/TrialWebGL/POC_WebGL/.

Advancing a more systematic approach to pooling national and organization-based training on PoC would, in turn, also reinforce PoC preparedness and mindset formation.

A PoC Preparedness Audit for NATO and NATO Allies

The pathway to PoC preparedness for NATO Allies is at least two-fold. First, Allies can directly implement NATO’s PoC framework by basing their policies, training, and exercises on NATO’s approaches. Second, given that many NATO members have been and are currently engaged in UN or EU operations that have PoC-tasks as part of their mandates, they also have the option to build their national PoC approaches on the UN PoC policy or the EU’s interpretation of the concept. With the second option, the questions of the similarities, differences, and compatibilities of the different organizations’ PoC approaches become relevant for assessing NATO Allies’ actual PoC preparedness. To assess NATO Allies’ PoC-preparedness, it makes sense to investigate the implementation of NATO’s PoC concept itself and map the state of NATO Allies’ implementation of other organizations’ concepts.

A national PoC preparedness audit could help to clarify the differences and similarities of different organization’s approaches and formulate recommendations on how governments and their ministry of defenses should implement their own PoC approach based on a ‘menu of choices’ of PoC approaches. Applied to a national PoC Audit within the context of NATO, a systematic approach should cover the following core aspects:

- Capturing experiences with PoC and PoC-related tasks during past NATO and non-NATO operations; considering PoC experiences in UN and EU operations and identifying lessons for NATO PoC approaches.

- Cataloguing knowledge about and perceptions of PoC across all branches and levels of the military hierarchy of NATO members’ armed forces.

- Undertaking a comprehensive analysis of existing national doctrinal documents about PoC and PoC-related tasks not exclusive or limited to NATO-led operations; and

- Conducting a capability gap analysis based on the core PoC tasks defined by NATO’s PoC policy and handbook as baseline tasks and conducted at the strategic, operational, and tactical levels.

By analyzing the findings of these different steps, a national PoC preparedness assessment allows for the identification of different perceptions and understandings of PoC among national military personnel; the existence of PoC-specific and PoC-relevant doctrine; the contrasting and comparing of perceptions, doctrine, and actual operational experience; and the available and necessary capabilities to operationalize and implement the protection of civilians from the political-strategic level down to the tactical level.

Capturing PoC Experiences

The systematic collection and analysis of NATO military experiences with PoC and PoC-related tasks and missions creates a picture of actual operational experience of protecting civilians, independent of the existence of dedicated PoC-guidelines, doctrine, and training. Thus, as outlined above, it becomes clear that even before developing a PoC-specific policy, NATO had some conception of PoC in a comprehensive framework. Core PoC-tasks, as seen through NATO’s conceptual lens, most notably the establishment of a safe and secure environment, have been components of the mandate of NATO operations such as the Stabilization Force in Bosnia and Herzegovina (SFOR) and the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF).19 Note: ‘SFOR Stabilisation Force in Bosnia and Herzegovina’, n.d., https://www.nato.int/sfor/docu/d981116a.htm; NATO, ‘ISAF’s Mission in Afghanistan (2001-2014)’, NATO, 30 May 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_69366.htm.

Cataloguing PoC Knowledge and Perceptions

Cataloguing PoC knowledge and perceptions can be challenging across the different definitions and concepts at NATO, the UN, and the EU. Interviews and surveys must be carefully designed to capture military leaders’ understanding of PoC-related tasks without drifting too much into ‘PoC-definition testing’. Even without explicit knowledge of PoC policies and doctrine, many military leaders have had experiences with implementing PoC tasks on the ground. What is more significant is getting a sense of PoC mindsets, leadership, and prioritizing PoC tasks within and across different units.

Comprehensive Doctrinal Analysis

To develop a comprehensive picture of the degree to which NATO Allies and partners have integrated a PoC-perspective into their policies, doctrine, and operational concepts, a comprehensive analysis of the existing body of relevant documents is critical. To mainstream the protection of civilians according to NATO’s PoC policy and Military Concept, this screening of NATO Allies’ and partners’ doctrinal landscape should encompass the political-strategic, operational, and tactical levels.

This assessment needs to extend to military education, training, and exercises and consequently include the curricula of military academies, educational facilities, officers, and NCO schools, as well as different training courses and relevant exercises across all branches. Many Allies and partners adopt NATO doctrine as their own, forgoing the process of developing separate national doctrines.20 Note: Dock, ‘Origins, Progress, and Unfinished Business’, 12. To be helpful, this assessment should not be limited purely to investigating the implementation of NATO PoC policy and concept but should also look at documents on the PoC-approaches of the UN and EU.

Lastly, when determining the criteria for which national documents count as relevant to PoC, it is useful to keep in mind that PoC is critical in all three of NATO’s core tasks—deterrence and defense, crisis prevention and management, and cooperative security—as set out in NATO’s new Strategic Concept adopted at the 2022 NATO Summit in Madrid. The strategic concept focused on the importance of Human Security (under which the protection of civilians sits as a cross-cutting topic).

PoC Gap Analysis

A comprehensive gap analysis is necessary to assess NATO Allies’ and partners’ overall PoC-capabilities and PoC-preparedness—both independently and when they act as part of the Alliance. We have outlined some core elements and methods for identifying critical tasks and baselines that should form the basis for a comprehensive gap analysis. Applied to NATO’s context, NATO’s PoC policy should be broken down into separate and distinct tasks, according to each of the policy’s thematic lenses: (1) Understand the Human Environment (UHE), (2) Mitigate Harm (MH), (3) Facilitate Access to Basic Needs (FABN), (4) Contribute to a Safe and Secure Environment (C-SASE). Following the identification of core tasks, a gap analysis should be carried out across the categories of Human Resources, PoC Mindset, Financial and Material Resources, Operational Experiences, Lessons Identified, Lessons Learned, Best Practices, Doctrines and Guidelines, Planning Capacities, Education, Training and Exercises, Support for broader political initiatives, Comprehensive Approach (organization and national level) as well as CIMIC/International Partnerships. This should be examined across the strategic-political, operational, and tactical levels. The results can then be illustrated with a simple ‘traffic-light’ color coding for fully prepared (Green), partially prepared (orange) and not prepared (red).

Lessons Identified and Opportunities for NATO

Based on the approach for a comprehensive PoC preparedness assessment introduced in this paper and the lessons identified from the German case study, we see the following opportunities for NATO Allies and partners:

Setting the Criteria

PoC is currently only one of five cross-cutting topics under NATO’s new Human Security approach.21 Note: See Marla Keenan and Samantha Turner, ‘NATO issues its much anticipated “Human Security Approach”’ (Washington D.C.: The Stimson Center, 2 November 2022), https://www.stimson.org/2022/nato-issues-its-much-anticipated-human-security-approach/ There are currently limited resources and scarce time for international staff at NATO’s Human Security Unit at HQ to focus on PoC and its further development and operationalization.22 Note: Andrew Hyde, ‘A Political and Diplomatic Case for Protection of Civilians at NATO’ (Washington, DC: The Stimson Center, 23 September 2021), https://www.stimson.org/2021/a-political-and-diplomatic-case-for-protection-of-civilians-at-nato/. This, however, does not mean that a coordinated and alliance-wide joint assessment of NATO’s PoC preparedness conducted at the behest of the North Atlantic Council (perhaps by external experts) is not in the cards. This is not an obstacle to a general stock-taking of the alliances’ fitness as PoC preparedness assessments if there is political will and resourcing. Plus, individual assessments can be undertaken by Allies using their national resources. As we have noted, these assessments can be conducted independently by member states willing to take the lead, provided that a standard frame of reference compatible with, but not necessarily limited to, NATO’s PoC concept is available to provide guidance and orientation for member states in their efforts to assess their PoC preparedness. To arrive at comparable results from this process, NATO should, at the minimum, offer its members and partners a PoC preparedness assessment framework. Other topics, such as Women, Peace and Security (WPS) also have this approach in their annual reporting requirements.

Pushing for PoC

Despite the protection of civilians being just one of the cross-cutting topics under the umbrella of ‘Human Security’ at NATO HQ, national military decision-makers are sensitive to the level of attention and placement of these different concepts on NATO’s agenda. An initiative to assess NATO’s PoC preparedness should be driven by a coalition of ‘friends of PoC’ who want to push for a clearly articulated operationalization of PoC within NATO. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the importance of protecting civilians in urban warfare should be a wake-up call that PoC is not a niche topic but one that will be squarely at the center of any Article 5 defensive operation, particularly in urban settings. It is, therefore, a critical moment to take the PoC agenda to the next level and mainstream it across all NATO’s core tasks of collective defense, crisis management, and cooperative security.

Conclusions and Ways Ahead

NATO has come a long way in developing PoC policies and guidelines and advancing its importance at the political-strategic level. Even before the adoption of its official PoC Policy in 2016, a wide range of core doctrines and operational experiences included elements very close to the current understanding and approach of an active PoC approach that goes beyond harm mitigation. At the same time, several NATO Allies have also developed their national PoC approaches and have been part of PoC discussions and operations in other organizational contexts, above all in the framework of UN peace operations. As the importance of protecting one’s own civilians becomes even more apparent in the context of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a comprehensive push for moving from policy to implementation is needed at all levels of the Alliance. The interplay between the organizational and national levels is of key importance here. However, to advance PoC implementation and operationalization, it is essential to know Allies’ and organizational structures’ current PoC preparedness, processes, and capacities. A PoC audit and gap analysis can provide valuable insights into the state of national PoC preparedness and how different PoC capacities could be shared across the Alliance. It can also help to identify which critical gaps need filling and which synergies could be enhanced with other international organizations. Germany has been the first Ally thus far to have undertaken a comprehensive PoC assessment and gap analysis to understand current capacities and future needs. The German PoC preparedness study was conducted with a strong focus on the UN PoC context and revealed the importance of the NATO-related PoC dimension. NATO could develop its own PoC audits and gap analyses across the Alliance by adopting or adapting Germany’s methodology for conducting PoC preparedness audits. This would offer an essential steppingstone for more evidence-based discussions on advancing and implementing the PoC agenda more concretely as the Alliance faces pressing challenges and security risks.

Notes

- 1Note: NATO, ‘NATO Policy for the Protection of Civilians Endorsed by the Heads of State and Government Participating in the Meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Warsaw’, NATO, 9 July 2016, para. 9, http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_133945.htm.

- 2Note: Joachim A. Koops and Christian Patz, ‘UN, EU, and NATO Approaches to the Protection of Civilians: Policies, Implementation, and Comparative Advantages’ (International Peace Institute, 10 March 2022), 5, https://www.ipinst.org/2022/03/un-eu-and-nato-approaches-to-the-protection-of-civilians.

- 3Note: Koops and Patz, ‘UN, EU, and NATO Approaches to the Protection of Civilians’, 4.

- 4Note: Kathleen H. Dock, ‘Origins, Progress, and Unfinished Business: NATO’s Protection of Civilians Policy’ (Washington, DC: The Stimson Center, 18 March 2021), 5, https://www.stimson.org/2021/origins-progress-and-unfinished-business-natos-protection-of-civilians-policy/.

- 5Note: ‘Protection of Civilians ACO Handbook’ (NATO, 11 March 2021), https://shape.nato.int/resources/3/website/ACO-Protection-of-Civilians-Handbook.pdf.

- 6Note: NATO, ‘Madrid Summit Declaration Issued by NATO Heads of State and Government (2022)’, NATO, n.d., para. 13, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_196951.htm; ‘NATO 2022 Strategic Concept’ (NATO, 29 June 2022), para. 39, https://www.nato.int/strategic-concept/.

- 7Note: Dr. David Kilcullen and Gordon Pendleton, ‘Future Urban Conflict, Technology, and the Protection of Civilians’ (Washington, DC: The Stimson Center, 10 June 2021), https://www.stimson.org/2021/future-urban-conflict-technology-and-the-protection-of-civilians/.

- 8Note: The 440 pages report and detailed gap analysis is not public, but a shortened executive version is due to be released in early 2023. For more information on the project, visit https://www.implementing-poc.com/

- 9Note: See, e.g., the presentation by Joachim A. Koops and Christian Patz, ‘Lessons Learned on PoC Experiences from Germany’, in PAX Protection of Civilians Conference 2020, n.d., https://protectionofcivilians.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Program-PAX-PoC-Conference-2020.pdf.

- 10Note: ‘Protection of Civilians ACO Handbook’, 7.

- 11Note: For an in-depth analysis of EU approaches to PoC and its relationship with NATO and UN PoC Approaches, see Koops and Patz, ‘UN, EU, and NATO Approaches to the Protection of Civilians’.

- 12Note: ‘Peace Support Operations AJP-3.4.1’ (NATO Standardization Office, July 2001), https://info.publicintelligence.net/NATO-PeaceSupport.pdf.

- 13Note: The study analysed 20 selected NATO Allied Joined Publications (AJPs) and German Military doctrine and guideline documents, containing more than 4524 separate paragraphs.

- 14Note: The study found over 1,470 PoC-relevant paragraphs related to UHE, 876 paragraphs relating to C-SASE as well as 748 and 659 relating to MH and FABN, respectively.

- 15Note: ‘Allied Joint Doctrine for Counterinsurgency (COIN) AJP-3.4.4 Edition A-1’ (NATO Standardization Office, February 2011), https://info.publicintelligence.net/NATO-Counterinsurgency.pdf; ‘Allied Joint Doctrine for Security Force Assistance AJP-3.16 Edition A-1’ (NATO Standardization Office, 14 August 2017), https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/allied-joint-doctrine-for-security-force-assistance-sfa-ajp-316a; ‘Allied Joint Doctrine for Stability Policing AJP-3.22 Edition A-1’ (NATO Standardization Office, July 2016), https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/628228/20160801-nato_stab_pol_ajp_3_22_a_secured.pdf; ‘Allied Joint Doctrine for Non-Combatant Evacuation Operations. AJP-3.4.2 Edition A’ (NATO Standardization Office, May 2013), https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/625781/doctrine_nato_noncombatant_evacuation_ajp_3_4_2.pdf; ‘Allied Joint Doctrine for Military Police AJP-3.2.3.3’ (NATO Standardization Office, 2009).

- 16Note: ‘Protection of Civilians ACO Handbook’, 11.

- 17Note: Austria has also developed a training course on PoC at the tactical level, but with less emphasis on scenario-based learning

- 18Note: ‘Human Security and the Military Role’, Norwegian Armed Forces, n.d., https://www.forsvaret.no/en/courses-and-education/human-security-and-the-military-role; NATO Virtual Reality PoC Course, n.d., https://review.c2ti.com/TrialWebGL/POC_WebGL/.

- 19Note: ‘SFOR Stabilisation Force in Bosnia and Herzegovina’, n.d., https://www.nato.int/sfor/docu/d981116a.htm; NATO, ‘ISAF’s Mission in Afghanistan (2001-2014)’, NATO, 30 May 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_69366.htm.

- 20Note: Dock, ‘Origins, Progress, and Unfinished Business’, 12.

- 21Note: See Marla Keenan and Samantha Turner, ‘NATO issues its much anticipated “Human Security Approach”’ (Washington D.C.: The Stimson Center, 2 November 2022), https://www.stimson.org/2022/nato-issues-its-much-anticipated-human-security-approach/

- 22Note: Andrew Hyde, ‘A Political and Diplomatic Case for Protection of Civilians at NATO’ (Washington, DC: The Stimson Center, 23 September 2021), https://www.stimson.org/2021/a-political-and-diplomatic-case-for-protection-of-civilians-at-nato/.