Ed Note — This first chapter of Military Coercion and US Foreign Policy is excerpted for readers interested in the book. It is available for purchase from Amazon or directly from the publisher, Routledge in hardback, paperback, or e-book.

Ch. 1 – Coercion in a Competitive World

Between 1991 and 2018, the United States was the world’s dominant power. With a productive economy and a federal government willing to spend generously on a military already well-advantaged relative to other countries, the United States “enjoyed uncontested or dominant superiority in every operating domain.… The US could generally deploy forces when we wanted, assemble them where we wanted, and operate how we wanted.”1US Department of Defense, Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy (Washington, DC: 2018), 3. Indeed, the US armed forces during this period undertook a breadth, depth, tempo, and duration of overseas activities that was historically unprecedented. These activities were component parts of national security strategies designed by a sequence of presidential administrations to protect the US homeland, to defend US strategic interests overseas, and to promote abroad the liberal values of individual rights and democracy.

In 2018, the US Government asserted that this post-Cold War era of primacy was over. What had in preceding years been diffuse prognosticating about an ascending China and an aggrieved and risk-acceptant Russia coalesced in the codification of these states as near-peer rivals in the 2018 National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy. This energized preparation for a new era of long-term competition, in which the United States is anticipated to contend increasingly, and more directly, with the interests of other states also in possession of considerable military and economic might.

National security leaders thus are preparing the United States to succeed at two related but not identical tasks: war, and competition. The requirements of war generally are well understood – even as they become increasingly technologically sophisticated – and preparing for it demands that the United States has, and knows how to use, the military assets needed to defeat all adversaries. Competition, however, demands that the United States find ways to discourage and therefore to minimize the frequency with which other actors choose to challenge US national security interests, and to find w

The idea of competition has captured the attention, imagination, and anxieties of national security practitioners. For historians and scholars of international politics, however, it is old hat. Indeed, a foundational premise of almost all theories seeking to explain why countries behave toward each other as they do is that the international environment is inherently competitive – that is, states perpetually are in contest with one another for advantage. 2John Mearsheimer offers the archetype realist summary of this dynamic: “Although the intensity of their competition waxes and wanes, great powers fear each other and always compete with each other for power. The overriding goal of each state is to maximize its share of world power, which means gaining power at the expense of other states.” John Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (New York: W.W. Norton, 2001). See also: Kenneth N. Waltz, Theory of International Politics (Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill, 1979); E.H. Carr, The Twenty Years’ Crisis (New York: Palgrave, 1981). Other paradigms, too, acknowledge that the international environment can be competitive, though differ in the extent to which this need be determinative of state behaviors. Finally, social constructivists argue that there is nothing inherent about the international environment at all, that, rather, it is competitive or cooperative by choice: Alexander Wendt, “Anarchy is What States Make of It: The Social Construction of Power Politics,” International Organization 46, no. 2 (1992): 391. Sometimes these contests manifest in ways that are direct, obvious, and violent, as happens in war, and sometimes they emerge as short-of-war tussles over, for example, diplomatic norms and standards, human rights, environmental conservation, trade, information exchange, and international law.

A state that competes successfully sets the terms of international life to suit its interests, as it understands them at any given time, more rather than less. It gets other actors to do more of what it wants, at the times of its choosing, in the ways that it likes, and it does so without first having to invade, occupy, or destroy. Exercising international leadership thus is both the work and the reward of competition. It is the work of establishing rules, of convincing as many actors to follow them as much of the time as is possible, and of incentivizing compliance and penalizing defiance such that the rules remain intact. The return is in the system’s structural privileging of that state’s interests over those of others. This prioritization can be instantiated in the nature, type, and activities of multinational regimes and institutions, but need not be. So too can it be evident in norms backed by no legal or organizational entity, in loosely-formed but common patterns of behavior, and in the simple requirement of considering how an action will be perceived and, possibly, addressed by the dominant state.

States, of course, are unlikely to tolerate this prioritization and follow rules set by another in the absence of a good reason to do so. Some may find that they agree with the rules because those rules suit their own material and instrumental interests, or because they comport with their values. For all other states, however, to be compelling and durable, the rules structure must promise and deliver either adequate benefit for good behavior, or adequate pain for bad. This means that the rule-setter must have the capability and the will to give and to take away, as required to assert and enforce standards and expectations.

Military, economic, and socio-political power therefore are the tools of the trade in competition. Socio-political power has been argued to be a means through which a state’s international leadership can be made more palatable. Indeed, strong arguments have been made that the appeal of individual rights, representative democracy, and market capitalism endowed the United States in the post-Cold War era with the power to attract. This so-called “soft power” is understood by some to lead other actors to view US dominance more favorably than they otherwise would, and so to conform more readily with its rule-based order.3Joseph S. Nye, Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics (New York: Public Affairs, 2004). Although there currently are no compelling empirical indicators to support this claim, there is a prima facie case to be made that having a domestic social and political culture with global appeal is more likely to be a net positive than negative.

The eruption of violent, radical Islamist backlash in the early 2000s, however, and its continuation today demonstrates that socio-political diffusion cuts both ways. So, too, does China’s international rise call into question the extent to which values, ideology, and identity will drive national strategies in the coming decades. China’s influence in the Indo-Pacific region, after all, has been won not with a galvanizing socio-political message, but rather through the creation of financial structures and trade regimes with, and direct investments in, the economies of growth-hungry neighbors, both regionally and those more far-flung.

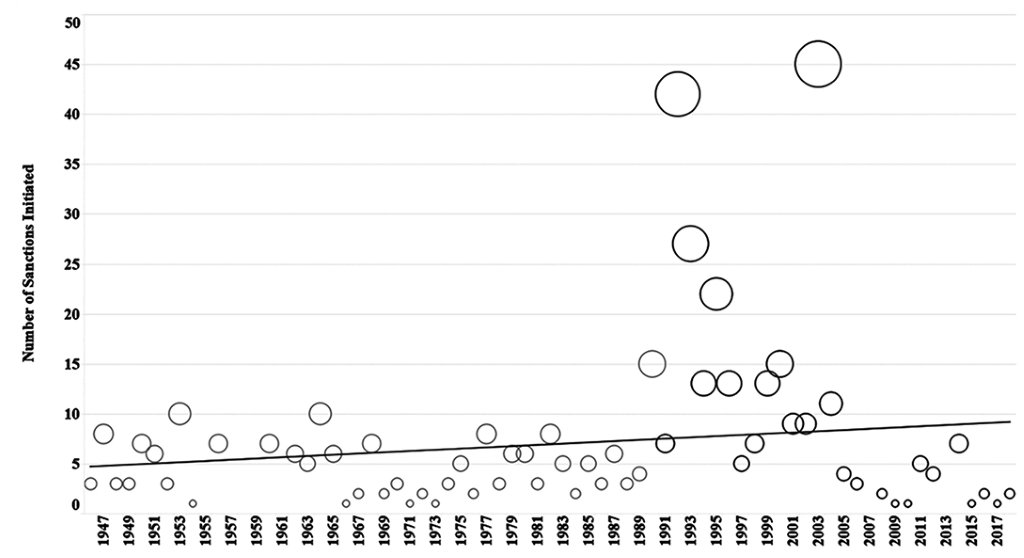

The United States, too, uses the integration of its economy with those of others through trade, finance, and investment for political purposes. Opportunity to export to the large US market, to import its goods, and to access its services are sizable inducements, while exclusion and, especially, expulsion from them can impose considerable pain. Economic sanctions in particular have increasingly become a tool of influence – while not new, their use has grown steadily since World War II, and accelerated markedly after the end of the Cold War (Figure 1.1). 4On the use of the national economy for political purposes see: Robert D. Blackwill and Jennifer M. Harris, War by Other Means (Cambridge, MA and London, UK: Belknap Press, 2016). Indeed, in the 44 years between 1946 and 1990 the United States initiated at least 191 sanctions on 74 states; in the 27 years between 1991 and 2018, those numbers increased to 252 sanctions on 101 states.

FIGURE 1.1 Sanctions initiated 1946–2018

Source: T. Clifton Morgan, Navin Bapat, and Yoshi Kobayashi, “The Threat and Imposition of Sanctions: Updating the TIES Dataset,” Conflict Management and Peace Science 31, no. 5 (2014): 541–58.

Economic power, of course, also is the foundation of conventional and nuclear military capabilities, the development, maintenance, and application of which are dependent upon a robust industrial base and healthily stocked government coffers. Although it is possible that technological advancements may change the nature of weapons such that this relationship is attenuated over time, for now, expensive, sophisticated and integrated systems, powerful platforms, large quantities of planes and ships and servicemembers, and the skills and abilities needed to use them effectively are essential for states seeking to compete successfully.

All of these tools are necessary, and none alone will be sufficient, for the United States to succeed in structuring international political life to prioritize its interests over the coming century. It will be the ability to use socio-political, economic, and military instruments in concert with one another, as integrated components of wise foreign policy managed deftly and with discipline, that will differentiate the rule-setter from the rule-follower, and that will separate peace from war.

This book is written to aid decisionmakers in this task, and to do so specifically as they consider whether and under what conditions the US armed forces should be called into use. Lessons are drawn from the 27 years of US preponderance between 1991 and 2018. Focus is on how and to what effect the United States used its armed forces, either independently or in conjunction with other instruments of foreign policy, to influence the behavior of other actors – to reinforce acceptable behaviors or to prevent or encourage the reversal of behaviors that ran counter to US interests. It is an examination, in other words, of how the United States went about coercing its global neighbors in the past to derive insights into how best to coerce them in the future.

War, not war, and coercion

By all objective measures, of course, the United States did not during these years have to try to coerce other states. Coercion was a choice, not an asymmetric strategy demanded by limited capabilities. As the most powerful country in the world, the United States had the option of simply imposing its will, of throwing the full weight of its considerable military might at any given problem, confident that, although perhaps costly, battles would not be fought at home and that the far superior US military would prevail. Yet, this was not often the course chosen by US leaders. Instead, the US armed forces frequently were used not to achieve the desired outcome directly, but rather to do so indirectly by persuading other actors to behave in ways the United States wanted them to.

That the United States used the military to achieve its desired ends through means short of war is not to say that the United States refrained entirely from the use of force. To the contrary, the US military deployed troops, dropped bombs, and launched missiles in pursuit of foreign policy aims on multiple occasions between 1991 and 2018. What, then, classifies these as violent acts of coercion and not as violent acts of war?

There is no definition of war that has been established and accepted by the community of US foreign policy professionals, or that is of standard use in the academic literature. Some of the institutions, organizations, and scholars that study war do not so much define war as delimit it based upon the characteristics of military violence. “Sustained combat,” for example, attaches thresholds to the duration and intensity of violence that enable cut-points between war and not-war. Others focus on the effects of violence. One of the most-known and most-used conflict datasets, for example, relies on counts of participants killed in combat (battle deaths), as a means of distinguishing between armed disputes and wars, ostensibly because battle deaths are a reasonable proxy for the size and scale of military effort.5“Datasets,” Correlates of War Project, accessed July 2, 2019. www.correlatesofwar.org/data-sets

Within the practitioner community, the most authoritative source on terminology is silent on the issue. Although the word “war” appears in the DoD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms more than 40 times, in none of those instances is it as an entry with its own definition. In all cases, rather, “war” is embedded in definitions of other terms, for example, “mobilization,” “neutrality,” “prisoner of war,” and “voluntary tanker agreement.”6U.S. Department of Defense, Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (Washington, DC: August 2018).

Among those who write on coercion, the tendency is to define what coercion is and to describe at length what it looks like, to be less specific and descriptive about what it is not, and to revert to dimensional characteristics when pressed to place events on one side of the line or the other. Comparisons are drawn between coercion, described as “an exemplary use of quite limited force,” or as “demonstrative uses of force,” and war, described as “full-scale military operations,” or “a full-scale use of force,” or “the use of force that is massive, at least to the target.” 7Alexander L. George, Forceful Persuasion (Washington, DC: U.S. Institute of Peace, 1991), 5–6; Robert J. Art and Patrick M. Cronin, eds, The United States and Coercive Diplomacy (Washington, DC: U.S. Institute of Peace, 2003), 9–10. Discerning the boundary between limited and full-scale uses of force, demonstrative or massive, is left open for interpretation.

In some cases, being definitive about the threshold between coercion and war isn’t necessary – as in the work of Thomas Schelling, for example, who produced an almost-literary exploration of the relationships between and among behavior, incentives, and communication in international politics.8Thomas C. Schelling, Arms and Influence, Henry L. Stimson Lectures (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008). His endeavor was to undertake rigorous theorizing, not systematic tests of his ideas against an empirical record. This latter clause is important because it is that task – the scrutiny of evidence done for purposes of explaining what has worked in the past and why, and what therefore may be more likely to work in the future, and why – that requires clear differentiation between the phenomenon one wants to study from all other phenomena. If one wants to be able to choose wine based on the likelihood that it will be delicious and not distasteful, one first must be able to recognize the difference between a bottle of wine and a jar of grape juice.

The work of which this book is a legacy established just such a means of operationalizing the distance between coercive uses of force and uses of force as war. In doing so, it advanced considerably the literature on coercion in international politics, although the authors did not describe its purpose in those terms. Rather, in the introduction to Force Without War, published in 1978, Barry Blechman and Stephen Kaplan state simply that they understand military force to be one among many instruments available for use in pursuit of political objectives.9Barry M. Blechman and Stephen S. Kaplan, Force without War: U.S. Armed Forces as a Political Instrument, (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1978); Carl von Clausewitz and F. N. Maude, On War (London: Routledge, 1966). The US military, in other words, is not a tool only of war, but rather also can be used as a tool of statecraft, independently or with diplomatic, economic, cultural, and other instruments of influence.

Because all military actions carry costs and risk – dispatching portions of the US armed forces is expensive and makes possible unintended escalations that can result in unwanted violence – Blechman and Kaplan’s intent in writing the book was to provide information that might increase the likelihood that future choices to use the armed forces to coerce would be made selectively and wisely. Information was to be derived from the historical record of instances in which the United States had used its military in the conduct of statecraft, as a means not of imposing an outcome but rather of communicating to other actors about the nature of US preferences and about behaviors that were desired, prescribed, or prohibited.

Because their exercise was empirical, they needed a means of differentiating use of the military as a tool of coercion from its use as a tool of war. They achieved this by focusing on the effect the use of force was intended to have, as follows:

Decisionmakers must have sought to attain their objectives by gaining influence in the target states, not by physically imposing the US will. When used as a martial instrument a military unit acts to seize an objective … or to destroy an objective.… In both of these examples, attainment of the immediate objective itself satisfies the purpose for which the force was used. [In coercion,] … the activity of the military units themselves does not attain the objective; goals are achieved through the effect of the force on the perceptions of the actor.10Blechman and Kaplan, Force without War, 13. It should be noted that the 2017 Joint Concept for Integrated Campaigning is unique among current official documents in its similar emphasis on distinguishing between uses of force to achieve a goal directly vs. indirectly, defining armed conflict as events in which “the use of violence is the primary means by which an actor seeks to satisfy its interests” (8).

Force, that is, is not used as a tool of coercion but rather as an act of war when it is designed to, “attain the immediate objective.” Conversely, it is an act of coercion when it is designed not to achieve the desired outcome directly, but rather to do so, “through the effect of the force on the perceptions of the actor.” The key distinction is the role of the other actor in determining the next step.

In the former case, where the military is used to attain the objective directly, the United States removes from the other party the option of making any choice other than to return fire or not to return fire, assuming it is in a position even to do that. In the latter, the United States retains greater space for the target to maneuver. In 1994, for example, the United States quite flamboyantly massed a force of 23,000 and readied it to sail to Haiti to fulfill its policy objective of regime change. The US military preparations, undertaken in conjunction with ongoing negotiations, were an indirect approach to achieving the policy goal: The move still allowed the Cedras junta, in power at the time, to choose whether to cede authority of its own volition or to experience a US invasion. Happily, Cedras opted to go quietly, and some US forces returned home while the remainder were converted to a peacekeeping force. Cedras may not have particularly liked that his options were constrained to, “step down without violence or have us remove you forcibly,” and yet he still had the opportunity to make a choice. Choice, then, is the conceptual lynchpin of this study. War removes choice; coercion retains and shapes it, albeit sometimes with a very firm hand, by adjusting the costs and benefits the target actor may expect to receive from the set of actions available to him.11On the role of cost/benefit in coercion: Robert Anthony Pape, Bombing to Win: Air Power and Coercion in War, Cornell Studies in Security Affairs (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996); Bruce Bueno de Mesquita. “The Costs of War: A Rational Expectations Approach,” The American Political Science Review 77, no. 2 (1983): 347; Christopher H. Achen, and Duncan Snidal, “Rational Deterrence Theory and Comparative Case Studies,” World Politics 41, no. 2 (1989): 143. doi:10.2307/2010405.

Determinants of coercive success

The years during which the United States was the sole superpower can be particularly instructive on the matter of coercion because they make clear that shaping another actor’s choice is a matter of more than the possession of military power, of threats to use force, and even of its actual use. Despite being an unrivaled superpower, the United States repeatedly confronted actors willing to challenge its preferences, and it did not in all cases prevail against them. Given, then, that simply having advantages on power indices relative to China, Russia, and the rest of the world did not guarantee the United States would get its way, there is a need to mine its mixed record of coercive successes and failures to ascertain, insofar as is possible, what separates the two.

This, of course, is not the first work to notice that power and foreign policy success don’t always go together. One prominent explanation addresses the effects of credibility, which is the extent to which one’s warnings about likely responses to infractions are to be believed.12For an excellent and thorough review of the academic literature on coercion, see: Daryl G. Press, Calculating Credibility: How Leaders Assess Military Threats (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005), chap. 1. The matter of credibility figured prominently, for example, in criticism of the Obama Administration’s attempt to coerce Syrian President Bashar al Assad to refrain from using chemical weapons during the Syrian civil war.

In 2012, President Obama made the now infamous statement that the use of such weapons by Assad would cross a “red line,” seeming to suggest that such use would produce a forceful US response. Ostensibly, the intent was to deter Assad; on that count the effort failed, as Assad instead continued to use noxious weapons to harm and terrorize Syrian civilians. As Alex Bollfrass recounts later in this book (see Chapter 4), Obama’s reticence to follow through on the red-line threat troubled advisers, most notably Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and National Security Advisor Susan Rice, who were concerned with the effects on US credibility of a weak or non-response.13Jeffrey Goldberg, “The Obama Doctrine,” The Atlantic, April 2016. External observers were similarly distressed at the implications of Obama’s restraint, worrying that an unwillingness to follow through on deterrent threats about weapons of mass destruction, of all things, could not but degrade perceptions of a willingness to follow through on deterrent threats about much of anything at all.

Obama has explained his decision, in part, as arising from a desire not to fetishize credibility, which is believed by many watchers of international affairs to operate as, “an intangible yet potent force – one that, when properly nurtured, keeps America’s friends feeling secure and keeps the international order stable.”14Ibid. It is possible, however, that credibility is not so much intangible as it is poorly understood. While at a conceptual level credibility has everything to do with the perceptions of others, it also is true that those perceptions are grounded in reality. Credibility is not like love, which requires no physical manifestation in order to exist. It is, rather, as its interchangeable use with “reputation,” “assurance,” and “trust” suggests, a product of what it is a country does and says. The problem is that there is no consensus on which combinations of what a country does and says, and of when and how it does them and says them that make its threats and inducements more or less believable.

Criticisms at the time, and since, of Obama’s decision not to follow through with strikes on Assad in 2013 have included assertions that it was especially damaging because it involved the threat to use military force; reduced the confidence of the US armed forces in the Commander in Chief; made Assad more likely to persist in his bad behavior; created permissive conditions that enabled Russia’s actions in Crimea and Ukraine; made the United States more likely to be challenged; and reduced the confidence of US allies everywhere in the stability of US commitments.15John McCain, “Obama Has Made America Look Weak,” op-ed, New York Times, March 14, 2014. https://warontherocks.com/2016/10/what-american-credibility-myth-how-and-why-reputation-matters/; Justin Sink, “Panetta: Obama’s ‘Red Line’ on Syria Damaged US Credibility,” The Hill, October 7, 2014. https://thehill.com/policy/international/219984-panetta-obamas-red-line-on-syria-damaged-us-credibility; Jeffrey Lewis and Bruno Tertrais, “The Thick Red Line: Implications of the 2013 Chemical-Weapons Crisis for Deterrence and Transatlantic Relations,” Survival 59, no. 6 (December 2017): 77–108. doi:10.1080/00396338.2017.1399729. This litany smuggles in claims that credibility operates over time, across actors and issue areas, and is not conditioned by context. All failures to follow through on a threat, by this logic, have equally bad effects today and into the future. Damage, moreover, occurs no matter the actors involved, the interests at stake, the reasons for backing down, or whether or not policy objectives were achieved (as Obama purports happened with the removal of most of Syria’s chemical weapons arsenal, despite – indeed perhaps because of – his non-use of force). Many of these propositions have been tested against the historical record, but little brush has been cleared, with findings at turns supporting and contradicting them.16Mark J. C. Crescenzi, “Reputation and Interstate Conflict,” American Journal of Political Science 51, no. 2 (2007): 382, accessed through EBSCOHost; Dianne Pfundstein Chamberlain, Cheap Threats: Why the United States Struggles to Coerce Weak States (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2016); Michael Tomz, Reputation and International Cooperation: Sovereign Debt across Three Centuries (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007); Alex Weisiger, and Keren Yarhi-Milo, “Revisiting Reputation: How Past Actions Matter in International Politics,” International Organization 69, no. 2 (April 2015): 473–95. doi:10.1017/S0020818314000393.

A related set of explanations for failures by states with overwhelming power to achieve their objectives focus on resolve, by which is meant the willingness to accept costs to achieve a desired outcome.17Resolve has been treated primarily within the context of war, though the concept is equally applicable to coercion. Steven Rosen, “War Power and the Willingness to Suffer,” in Peace, War, and Numbers, ed. Bruce M. Russet (Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 1972), 167–84; Andrew Mack, “Why Big Nations Lose Small Wars: The Politics of Asymmetric Conflict,” World Politics, 27, no. 2 (1975), 175–200; Diane Pfundstein Chamberlain, Cheap Threats: Why the United States Struggles to Coerce Weak States (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2016) More specifically, explanations focused on resolve emphasize that the weaker actor in an exchange usually has serious interests at stake – interests that in fact may be existential. The strong state, by contrast, has interests at stake serious enough to have engaged the issue, and yet not so serious as those motivating the challenger. This disparity suggests that the weaker party will be highly resistant to being coerced – it has vital interests at stake, for which it is likely to be willing to tolerate pain, even over long periods of time. Because this imbalance of interests is recognizable prior to the start of military action, moreover, relative resolve can interact in unhelpful ways with beliefs about the stronger state’s credibility. It is reasonable, that is, to conclude that bluster, shows of force, and even limited uses of force notwithstanding, when push comes to shove the stronger actor either won’t follow through in full, or will do so only so long as it suffers little to no cost. This dynamic may be particularly powerful in liberal democracies, where state leaders are constrained by the preferences of their voting populations.18Michael Tomz, “Domestic Audience Costs in International Relations: An Experimental Approach,” International Organization 61, no. 4 (2007): 821, accessed through EBSCOHost; Christopher Gelpi, Peter Feaver, and Jason Aaron Reifler. Paying the Human Costs of War: American Public Opinion and Casualties in Military Conflicts. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009); Gil Merom, How Democracies Lose Small Wars: State, Society, and the Failures of France in Algeria, Israel in Lebanon, and the United States in Vietnam (Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003); Kenneth A. Schultz, “Domestic Opposition and Signaling in International Crises,” The American Political Science Review 92, no. 4 (1998): 829. doi:10.2307/2586306.

Indeed, the United States during the post-Cold War era gained an unfortunate reputation for having a low cost-tolerance – for US blood, if not for treasure.19Dana Priest, “Fear of Casualties Drives Bosnia Debate,” Washington Post, December 2, 1995. www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1995/12/02/fear-of-casualties-drives-bosnia-debate/b7481408-0449-4bf6-825f-1f43a34194e7/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.443ed80ae83d; Melinda Penkava, “Casualty Aversion,” November 11, 1999, radio broadcast, NPR. www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=1066450; M.S., “Casualty Aversion Leads to Casualty Displacement,” The Economist, April 12, 2010. www.economist.com/democracy-in-america/2010/04/12/casualty-aversion-leads-to-casualty-displacement; Christopher A. Preble, “Will Public Aversion to Casualties Constrain Trump’s War-Making Instincts?” CATO at Liberty (blog), CATO Institute August 10, 2017. www.cato.org/blog/will-public-aversion-casualties-constrain-trumps-war-making-instincts It is hard to say that the US did not earn such a reputation during this period given its repeated retrenchments, hesitations to make good on threats, and outright statements of unwillingness to commit ground troops in pursuit of foreign policy outcomes. Balkans expert William Durch’s treatment in this book of US efforts to coerce Slobodan Milosevic in the 1990s (see Chapter 6) illustrates well how the Clinton Administration’s cost-sensitivity, most especially its casualty aversion, resulted in prevarications and half-measures that repeatedly proved ineffective, negatively affected perceptions of US resolve, and thereby contributed to prolonging the conflict at great cost to the Bosniac and Kosovar populations.

A third explanation for why the United States did not experience frequent or easy coercive success during the post-Cold War period suggests that it is the characteristics of the target actor that matter: its institutions of governance, its internal and regional cultures, and the personalities of its leaders.20Michael C. Horowitz, Philip Potter, Todd S. Sechser, and Allan Stam, “Sizing Up the Adversary Leader Attributes and Coercion in International Conflict,” Journal of Conflict Resolutions 62, no. 10 (2018): 2180–204, accessed July 2, 2019. doi:10.1177/0022002718788605. This proposition of course has considerable intuitive appeal – it seems obviously true that the temperament, culturally mediated worldview, and character of who’s in charge, and how much they are in charge of, matter.

This reasoning could suggest that outcomes are wholly contingent on individuals; there are no generalizable principles or practices of coercion that are more or less likely to succeed in any given case. Such a categorical rendering, however, does a disservice to the real implications of the argument, which are both more nuanced and more useful.

In his contribution to this book, for example, scholar and former intelligence official Kenneth Pollack takes up the matter of leadership particularities as influences on foreign policy outcomes (see Chapter 5). Although it has become almost standard trope to conclude the US failed to coerce Saddam Hussein during the 1990s either because US efforts were not forceful enough, or because Hussein was entirely irrational and therefore not coercible, Pollack’s detailed examination of US military actions during this period produces a different lesson. Indeed, Pollack’s work raises as an alternative the proposition that although Hussein suffered at least from denial and at most from delusion, he nonetheless did have a prioritized order of interests – including domestic political control, regional standing, and of course regime survival – and that he behaved in ways consistent with that ordering. The case thus suggests strongly that the United States did a poor job of understanding, much less of manipulating, Saddam’s incentive structure.

The essence of coercive action, then, is communication. It is the reduction of an adversary’s uncertainty not only about US capability – about which there was little question during the post-Cold War era – but also about its willingness to suffer costs to achieve a desired outcome.21On uncertainty in international conflict see: Kristopher W. Ramsay, “Information, Uncertainty, and War,” Annual Review of Political Science 20 (2017): 505.

It is safe to assume that US policymakers by now are well aware of the importance of resolve and credibility and that reiterating the truism does nothing more than beg the question. That is, the need to be met is to identify specific behaviors and actions that are more effective than others at communicating resolve and at establishing credibility.

There is a robust and growing literature on communication, often referred to as signaling, in international relations that is both theoretically rich and, increasingly, subject to empirical examination.22James D. Fearon, “Signaling Foreign Policy Interests: Tying Hands Versus Sinking Costs,” Journal of conflict Resolution 41, no. 1 (1997): 68; Keren Yarhi-Milo, Joshua D. Kertzer, and Jonathan Renshon, “Tying Hands, Sinking Costs, and Leader Attributes,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 62, no. 10 (2018): 2150. These works have produced a number of logical and intuitive propositions about how foreign policy tools, especially but not exclusively the military, can be used to self-inflict costs and thereby affirm a seriousness of intent. Although the intent of this work is not explicitly to test any one of these theories or the paradigms of which they are a part, many of the propositions they have rendered, along with anecdotal and conventional wisdoms invoked in public policy discourse, are implicated in the analyses contained in the chapters that follow. The results are sometimes surprising, indicating at the very least that there is much to gain from expanding the scope of the inquiry presented here.

Finding successful coercive strategies

This book has two primary purposes. The first is to provide information about the conditions under which particular types, sizes, and uses of the US military increased or decreased the likelihood of coercive success during the period 1991–2018. The second is to determine how uses of the US military were, or were not, integrated with other tools of foreign policy in ways that enhanced or degraded US credibility, that communicated accurately or inaccurately US resolve, and that accessed well or poorly the target actor’s values and goals. It is hoped that knowledge of these past events will serve decisionmakers well as they assess contemporary conditions and select which tools to use, when to use them, and how to use them to achieve US national security objectives.

The chapters that follow address the full range of short-of-war activities undertaken by the United States military, 1991–2018. This includes descriptions in Chapter 2 of such long-term activities as overseas basing and presence, medium-term engagements like partner security assistance and training programs, regular and routine activities such as overseas exercises, and overtures such as port visits and aircraft fly-bys, among others. Although the focus of the book is on short-of-war activities, it would be misleading not to account for the enormous effort undertaken by the US military to defeat terrorist groups worldwide, and so Chapter 2 also accounts for the scale and scope of these operations.

With this context established, the book then examines the set of publicly reported non-routine, coercive military actions used to achieve specific goals, relative to specific actors, during the period 1991–2018. These roughly 100 instances of US efforts to deter and compel others are analyzed statistically to reveal relationships between US military actions, targeted actors, the interests under dispute, the economic and political context, and whether the United States achieved its goals. The analyses generate sometimes unexpected findings about combinations of US military, political, and economic actions that proved more, or less, successful in achieving US objectives in different contexts. This information can provide useful points of comparison for decision-makers contemplating whether or how to use the armed forces as part of coercive strategies today and into the future.

The insights generated by statistical analysis are complemented in Chapters 4–9 by in-depth narrative studies of important coercive exchanges. The cases were not selected to test any specific hypotheses, much less a broader theory, about US military coercion during the period 1991–2018. Authors were instead at liberty to explore US communication, credibility, and resolve as they saw fit. These chapters therefore vary somewhat in style and approach, but each focuses on significant examples of US military coercion and was contributed by an expert with subject matter expertise gained through direct experience and years of study.

Alex Bollfrass (Chapter 4) examines US military actions – those threatened, and those carried out – relative to Syria during both the Obama and the Trump Administrations. Locating these events within the broader context of US interests in the Middle East, the chapter highlights the role in coercion of internal administration processes and interpersonal jostling, of the consequences of uncertainty about a target actor’s interests and motivations and – in the form of Russia’s capitalizing on Secretary of State John Kerry’s off-the-cuff suggestion that chemical disarmament might resolve the dispute – of the occasional benefits of accidental diplomacy.

Kenneth Pollack (Chapter 5) provides another view of US coercion in the Middle East between 1991 and 2018, providing nuanced and expert analysis of US military activities relative to Iraq and Iran. In addition to drawing together neatly the otherwise unruly threads of Middle Eastern politics and the US role in them, Pollack makes a compelling case for the negative effects on military coercion not of a lack of information about a target’s interests and motivations, but rather of an inadequate understanding thereof. Indeed, it is difficult to put Pollack’s chapter down without acknowledging that US perceptions of Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, and so its strategies of coercion, were the product of confirmation bias rather than of sensitive analysis, to the detriment of US objectives.

Pollack’s treatment of US interactions with Iran, by contrast, offer a view of two states approaching each other with caution, with both at turns absorbing potentially provocative activities rather than risking escalation. Pollack’s account suggests that Iran’s behavior during this period reflected both a respect for sheer US military might and a recognition on the part of its leadership that there was more to gain from managing the relationship than igniting it. Conversely, US behavior was at turns defined by preoccupations elsewhere and a desire not to become embroiled in yet another theater of conflict, most especially with a regime that had evidenced itself to be both capable and determined. It is worth noting, as the United States looks ahead, that Pollack’s careful tracing of events indicates that the majority of US gains were made, most especially those to do with Iran’s nuclear program, when its policy was either to sanction, or to engage in military activity, but not both.

In the European theater, William Durch (Chapter 6) provides a chapter full of insightful observations about the choices made by the United States and its NATO allies in their efforts to coerce Yugoslav leader Slobodan Milosevic. Far from simply identifying consequential operational missteps, however, Durch’s recounting of events in Bosnia and Kosovo also makes evident that two strategic misconceptions joined to prolong a tragically violent and brutal period in European history. The first was Milosevic’s belief that the NATO alliance could be fractured, a ghost onto which he held until a true preponderance of evidence convinced him otherwise. The second was a US/NATO misunderstanding of the historical legacies and instrumental interests that motivated Milosevic’s actions. These mutual misconceptions created a vicious cycle, in which the United States and NATO used plenty of kinetic force, but in the wrong places and ways, which only reaffirmed Milosevic’s belief in NATO’s lack of coherence and fortitude, and so the violence continued.

Thomas Wright (Chapter 7) also takes up the question of US and NATO collaboration in his chapter, specifically within the context of efforts to deter Russia. Wright moves incisively through the US policy positions, processes, and behaviors before, during, and after Russia’s successful gambits in Crimea and eastern Ukraine. Of particular note is his pointed observation that the United States has been flat-footed and slow, equivocal in its expressions of commitment to NATO’s far flanks and Russia’s near-abroad, and yet still willing to enhance its troop presence, undertake military exercises, and expand NATO-specific defense spending. The chapter thus is effective in provoking the question of how long the United States will be able to maintain this type of strategic equivocation and, if the answer is not long, what the proper recourse will be. Indeed, it is difficult not to think that the United States soon will need to determine whether its deterrent objectives in Europe are met best by a larger permanent presence, by NATO interoperability, by so-called dynamic force employment, or by something else entirely.

Finally, Michael Chase (Chapter 8) turns attention to US short-of-war moves used to communicate with China. As much as Russia has demonstrated that luck is when preparation meets opportunity, China has demonstrated an extent of strategic patience and a degree of operational creativity that pose new and paradigm-breaking challenges for the United States. Tracking the interplay between China’s non-traditional moves and the more conventional US ripostes, Chase’s chapter is a caution in over-endowing US military activity with expectations of immediate success, as much as it is an entreaty for the United States to understand near-term interactions within the long-term strategic context – in which the real currency is less military capability and more regional influence.

Taken together, this collection of detailed work not only adds historical depth and richness to important coercive events but also brings to the fore important lessons about coercive strategy. Each study notes instances in which US communication of the behaviors desired of the targeted actor was ambiguous or bombastic – and, occasionally, both – characteristics that common sense suggests militate against accurate interpretation of demands, much less behavioral compliance. Each study observes the importance of understanding, as well as is possible, the interests and values that motive the target’s behavior. Each study identifies contextual characteristics – alliances, economic relationships, power dynamics – that might affect the outcome of any immediate coercive exchange. And each study emphasizes that coercion requires the careful coordination of multiple tools of influence; military power alone was in no case adequate to achieve US policy objectives short of war.

The outcome of this study is not a new theory of coercion, a typology associating leadership psychology with coercibility, a guide to enhancing national resolve, or a protocol of hard and fast rules that, if only followed, will guarantee coercive success. Each chapter, however, does produce stand-alone lessons; and these, when drawn together as a collective set in the concluding chapter, offer guidance about the construction of effective coercive strategy.

The need for such strategies is again acute, as the United States faces a less pliable and increasingly contested international environment. It is unrealistic to believe that the world soon will be populated only by states satisfied with the status quo, and it would be irresponsible for US leaders to behave as though possessing the most able war-fighting force in the world will suffice to address the full spectrum of interstate frictions and conflicts. The United States must be prepared to manage provocation, incrementalism, and defiance. This imperative sits alongside the ever-present specter of interstate war. Navigating the line between the two will require US decisionmakers to take great care in the design of policies that include use of the US armed forces, and to practice great discipline in their implementation. The consequences of failure on either count may be severe.

Reviews

“So often, revisions fall short of distinguished predecessors. In this case, we see brilliance built on brilliance as the seminal work, Force Without War, is brought up to the present by a trenchant team of scholars and practitioners. This new volume will clearly become a well-thumbed textbook in our nation’s war colleges and military academies. As a combatant commander in both Latin America at US Southern Command and later in four years as NATO Supreme Allied Commander, I often turned to the original study – this new book will illuminate the path ahead for my successors in senior command.”

Admiral Jim Stavridis (USN ret.)

“The post-Cold War era will soon be as long as the Cold War was. Military Coercion and US Foreign Policy could not be more timely. It is not only a masterful updating of a classic study, but a thorough and wide-ranging assessment of the relevance – real and perceived – of American military power in a world where interests, adversaries, and conflicts interact in more complicated ways than ever.”

Richard K. Betts, Columbia University, USA

“This impressive edited volume updates one of the classic books on coercion as a tool of US foreign policy, bringing Force Without War up to the present day and providing key lessons for the future. It combines statistical analysis with detailed case studies, written by noted experts, to show where and how military coercion can help achieve US national objectives without resorting to large-scale military operations. Its findings will be especially helpful for the policymakers charged with navigating through today’s turbulent strategic environment, and finding ways to successfully compete with Russia, China, and others without escalating into major war.”

Nora Bensahel, Johns Hopkins School of AdvancedInternational Studies, Washington DC, USA, and Contributing Editor War on the Rocks

“Building on the work that Barry Blechman, Stephen Kaplan, and colleagues did in one of the best defense studies of the 1970s, Force Without War, this 21st-century Stimson team has again asked the question, based on more recent cases (and even more rigorous methodology), ‘How well does the deployment or employment of American military power serve the stated objectives of the United States in various crises around the world?’ The approach is careful and specific – looking for tangible, tactical and measurable effects, rather than waxing on about overall foreign policy outcomes. In other words, this book provides the kind of analytical and falsifiable research that characterizes the best of modern social science – but with the savvy and practicality of Washington insiders who understand how US foreign policy is actually made. It turns out that force ‘works’ in this way about half the time. Perhaps even more interesting are the book’s findings about when force is most likely to be effective and when it is not. For example, sending one aircraft carrier to a crisis turns out to be about as effective as sending several. And deploying US forces shoulder-to-shoulder with strong allied participation makes a significant positive difference as well. The findings provide extremely helpful grist for policymakers deciding when and if to send US military forces to deter or compel American adversaries.”

Michael O’Hanlon, Brookings Institution, Washington DC, USA

Notes

- 1US Department of Defense, Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy (Washington, DC: 2018), 3.

- 2John Mearsheimer offers the archetype realist summary of this dynamic: “Although the intensity of their competition waxes and wanes, great powers fear each other and always compete with each other for power. The overriding goal of each state is to maximize its share of world power, which means gaining power at the expense of other states.” John Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (New York: W.W. Norton, 2001). See also: Kenneth N. Waltz, Theory of International Politics (Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill, 1979); E.H. Carr, The Twenty Years’ Crisis (New York: Palgrave, 1981). Other paradigms, too, acknowledge that the international environment can be competitive, though differ in the extent to which this need be determinative of state behaviors. Finally, social constructivists argue that there is nothing inherent about the international environment at all, that, rather, it is competitive or cooperative by choice: Alexander Wendt, “Anarchy is What States Make of It: The Social Construction of Power Politics,” International Organization 46, no. 2 (1992): 391.

- 3Joseph S. Nye, Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics (New York: Public Affairs, 2004).

- 4On the use of the national economy for political purposes see: Robert D. Blackwill and Jennifer M. Harris, War by Other Means (Cambridge, MA and London, UK: Belknap Press, 2016).

- 5“Datasets,” Correlates of War Project, accessed July 2, 2019. www.correlatesofwar.org/data-sets

- 6U.S. Department of Defense, Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (Washington, DC: August 2018).

- 7Alexander L. George, Forceful Persuasion (Washington, DC: U.S. Institute of Peace, 1991), 5–6; Robert J. Art and Patrick M. Cronin, eds, The United States and Coercive Diplomacy (Washington, DC: U.S. Institute of Peace, 2003), 9–10.

- 8Thomas C. Schelling, Arms and Influence, Henry L. Stimson Lectures (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008).

- 9Barry M. Blechman and Stephen S. Kaplan, Force without War: U.S. Armed Forces as a Political Instrument, (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1978); Carl von Clausewitz and F. N. Maude, On War (London: Routledge, 1966).

- 10Blechman and Kaplan, Force without War, 13. It should be noted that the 2017 Joint Concept for Integrated Campaigning is unique among current official documents in its similar emphasis on distinguishing between uses of force to achieve a goal directly vs. indirectly, defining armed conflict as events in which “the use of violence is the primary means by which an actor seeks to satisfy its interests” (8).

- 11On the role of cost/benefit in coercion: Robert Anthony Pape, Bombing to Win: Air Power and Coercion in War, Cornell Studies in Security Affairs (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996); Bruce Bueno de Mesquita. “The Costs of War: A Rational Expectations Approach,” The American Political Science Review 77, no. 2 (1983): 347; Christopher H. Achen, and Duncan Snidal, “Rational Deterrence Theory and Comparative Case Studies,” World Politics 41, no. 2 (1989): 143. doi:10.2307/2010405.

- 12For an excellent and thorough review of the academic literature on coercion, see: Daryl G. Press, Calculating Credibility: How Leaders Assess Military Threats (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005), chap. 1.

- 13Jeffrey Goldberg, “The Obama Doctrine,” The Atlantic, April 2016.

- 14Ibid

- 15John McCain, “Obama Has Made America Look Weak,” op-ed, New York Times, March 14, 2014. https://warontherocks.com/2016/10/what-american-credibility-myth-how-and-why-reputation-matters/; Justin Sink, “Panetta: Obama’s ‘Red Line’ on Syria Damaged US Credibility,” The Hill, October 7, 2014. https://thehill.com/policy/international/219984-panetta-obamas-red-line-on-syria-damaged-us-credibility; Jeffrey Lewis and Bruno Tertrais, “The Thick Red Line: Implications of the 2013 Chemical-Weapons Crisis for Deterrence and Transatlantic Relations,” Survival 59, no. 6 (December 2017): 77–108. doi:10.1080/00396338.2017.1399729.

- 16Mark J. C. Crescenzi, “Reputation and Interstate Conflict,” American Journal of Political Science 51, no. 2 (2007): 382, accessed through EBSCOHost; Dianne Pfundstein Chamberlain, Cheap Threats: Why the United States Struggles to Coerce Weak States (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2016); Michael Tomz, Reputation and International Cooperation: Sovereign Debt across Three Centuries (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007); Alex Weisiger, and Keren Yarhi-Milo, “Revisiting Reputation: How Past Actions Matter in International Politics,” International Organization 69, no. 2 (April 2015): 473–95. doi:10.1017/S0020818314000393.

- 17Resolve has been treated primarily within the context of war, though the concept is equally applicable to coercion. Steven Rosen, “War Power and the Willingness to Suffer,” in Peace, War, and Numbers, ed. Bruce M. Russet (Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 1972), 167–84; Andrew Mack, “Why Big Nations Lose Small Wars: The Politics of Asymmetric Conflict,” World Politics, 27, no. 2 (1975), 175–200; Diane Pfundstein Chamberlain, Cheap Threats: Why the United States Struggles to Coerce Weak States (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2016)

- 18Michael Tomz, “Domestic Audience Costs in International Relations: An Experimental Approach,” International Organization 61, no. 4 (2007): 821, accessed through EBSCOHost; Christopher Gelpi, Peter Feaver, and Jason Aaron Reifler. Paying the Human Costs of War: American Public Opinion and Casualties in Military Conflicts. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009); Gil Merom, How Democracies Lose Small Wars: State, Society, and the Failures of France in Algeria, Israel in Lebanon, and the United States in Vietnam (Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003); Kenneth A. Schultz, “Domestic Opposition and Signaling in International Crises,” The American Political Science Review 92, no. 4 (1998): 829. doi:10.2307/2586306.

- 19Dana Priest, “Fear of Casualties Drives Bosnia Debate,” Washington Post, December 2, 1995. www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1995/12/02/fear-of-casualties-drives-bosnia-debate/b7481408-0449-4bf6-825f-1f43a34194e7/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.443ed80ae83d; Melinda Penkava, “Casualty Aversion,” November 11, 1999, radio broadcast, NPR. www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=1066450; M.S., “Casualty Aversion Leads to Casualty Displacement,” The Economist, April 12, 2010. www.economist.com/democracy-in-america/2010/04/12/casualty-aversion-leads-to-casualty-displacement; Christopher A. Preble, “Will Public Aversion to Casualties Constrain Trump’s War-Making Instincts?” CATO at Liberty (blog), CATO Institute August 10, 2017. www.cato.org/blog/will-public-aversion-casualties-constrain-trumps-war-making-instincts

- 20Michael C. Horowitz, Philip Potter, Todd S. Sechser, and Allan Stam, “Sizing Up the Adversary Leader Attributes and Coercion in International Conflict,” Journal of Conflict Resolutions 62, no. 10 (2018): 2180–204, accessed July 2, 2019. doi:10.1177/0022002718788605.

- 21On uncertainty in international conflict see: Kristopher W. Ramsay, “Information, Uncertainty, and War,” Annual Review of Political Science 20 (2017): 505.

- 22James D. Fearon, “Signaling Foreign Policy Interests: Tying Hands Versus Sinking Costs,” Journal of conflict Resolution 41, no. 1 (1997): 68; Keren Yarhi-Milo, Joshua D. Kertzer, and Jonathan Renshon, “Tying Hands, Sinking Costs, and Leader Attributes,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 62, no. 10 (2018): 2150.