For the first time ever, a near-real time picture of how major dams and climate conditions impact the Mekong’s hydrological conditions is publicly available for policy makers, downstream communities, researchers, and activists. The Mekong Dam Monitor will improve transboundary river governance and increase the capacity of downstream stakeholders to negotiate for an equitable share of water. Importantly, the monitor also provides a valuable early warning signal of impeding flood and drought in the lower Mekong basin.

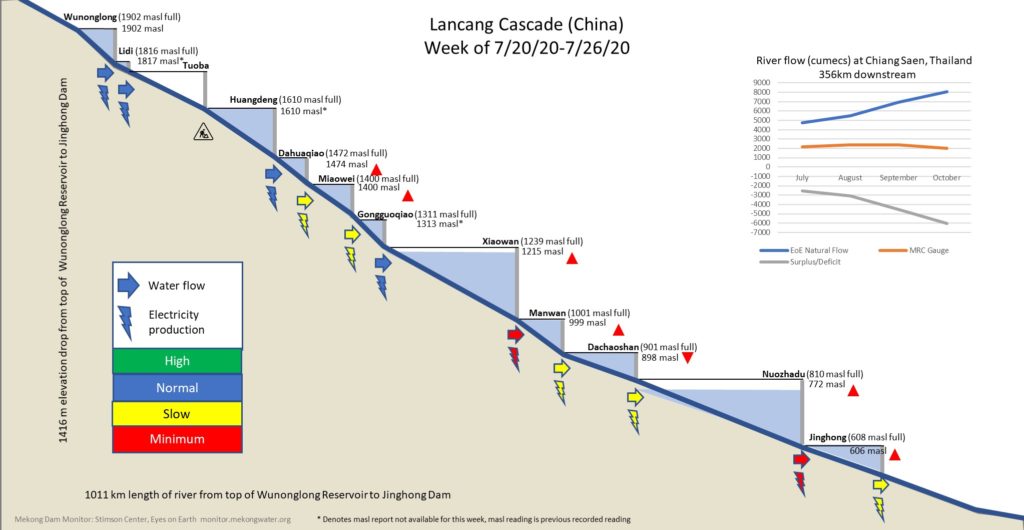

The Mekong Dam Monitor enhances transparency on the upstream operations of China’s 11 upper mainstream Mekong dams through weekly reporting of reservoir conditions and visualization of how these dams are operated as a cascade. To date, no information about the conditions and operations of these upstream dams has been shared outside of China. A mounting body of evidence suggests that upstream dams are changing the natural flow cycle of the Mekong mainstream affecting agricultural productivity downstream and the world’s largest freshwater fishery. More than 60 million people in Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Myanmar, and China rely on the mighty Mekong’s natural resource base and fish and agricultural products produced by the river’s natural hydrological cycle feed mainland Southeast Asia and are exported throughout the world. In April 2020, Eyes on Earth published a U.S. State Department-supported study with evidence that upstream dams restricted enormous quantities of water while the downstream experienced an unprecedented 2019 drought. These restrictions exacerbated existing drought conditions caused by a lack of precipitation.

New Findings

The Mekong Dam Monitor provides a much more comprehensive picture of the operations and impacts of upstream dams. Historical data in the monitor shows added reservoirs filling over time, which adds to the total amount of water permanently held in the reservoirs behind dams. The monitor also shows how China’s giant Xiaowan and Nuozhadu dams, which collectively hold about as much water as in the Chesapeake Bay, are the major drivers of hydrological changes to the river’s natural flow cycle downstream.

The monitor provides no evidence of an intentional geo-strategic plot by China to manipulate river flow in a way to expand its influence downstream. However, the monitor discounts recent claims that upstream dams provide important benefits of flood control and drought relief to downstream countries by controlling the flow of water in the upper basin. The monitor’s Lancang cascade visualization shows how these dams are now coordinated and operated in a way to maximize the production of hydropower for sale to China’s eastern provinces with insufficient consideration given to downstream impacts. Satellite imagery on the monitor shows how these dams are driven to their lowest levels in order to produce hydropower during the first half of every year, while restricting water during the latter half of the year; effectively, turning off the tap at times when water is critically needed downstream. The platform shows how 2020 was mostly a repeat performance of 2019 with China’s cumulative dam restrictions from July 2020 through the present totaling about 20 billion cubic meters of water through a period when the downstream reaches once again hit all-time lows during an anomalously dry wet season.

The Monitor is a first attempt at scrutinizing dams and river flow throughout the entirety of the Mekong Basin. The platform monitors environmental impacts and hydrological changes to four areas along the river often watched by Mekong watchers and the media. Users of the platform will see how riverside farms in the Golden Triangle are unexpectedly inundated by China’s upstream dam releases during the Mekong’s dry season. Conversely, it reveals how the mainstream rocky riverbed at Pak Chom along the Thai-Lao border during the wet season when the river level is typically high. Further emphasis is placed on findings along the Tonle Sap Lake, Southeast Asia’s largest lake, which floods from the Mekong mainstream every wet season, thereby supporting the world’s largest inland fish catch. The monitor currently shows the Tonle Sap Lake at record low levels during the critical season of the year. Users of the platform will see how the shoreline of the lake – the beating heart of the Mekong – receded about one kilometer from its normal shoreline in 2020. The impacts of this extreme event is a direct consequence of upstream manipulation from dams and a drought above the Tonle Sap Lake.

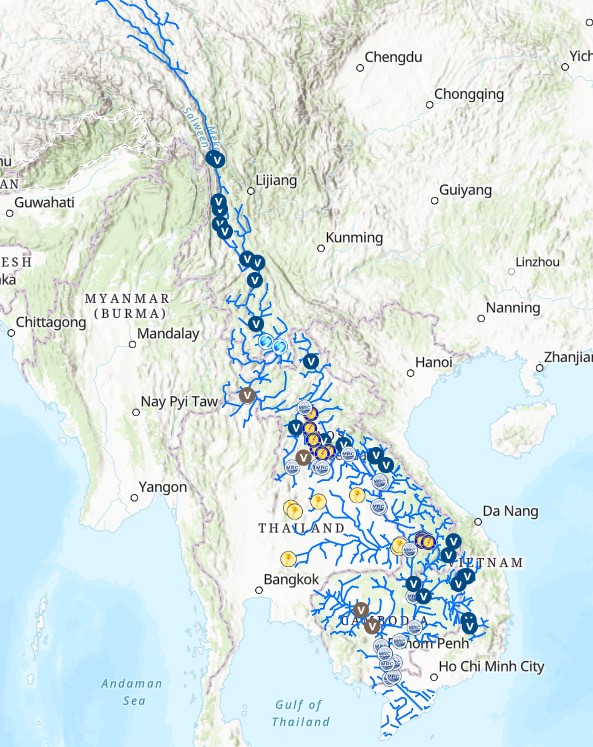

The platform also monitors the newly commissioned Xayaburi Dam and Don Sahong Dam on the Mekong mainstream in Laos. Moreover, it provides flow information on fourteen tributary dams in Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. The monitor also includes data Cambodia’s Lower Sesan 2 dam which is predicted (by peer review studies) to reduce the Mekong’s total fish population by 9.3%.

Key Features

Stimson’s major contribution to the platform is the concept of a “virtual gauge”. This is a novel approach to river monitoring with significant implications for data transparency and decision support in the Mekong basin. The same approach and technology can be applied to bodies of fresh water all over the world. Virtual gauges provide estimates of water level for a rivers, lakes, or reservoirs where in situ – physically collected data – is absent – or where data is measured but not shared with stakeholders who have a right to know such information. The Stimson team uses Sentinel-1 imagery and GIS processes to determine an estimate for which a validation model shows the margin of error is +/1 meter. The monitor also includes satellite imagery allowing the user to see with their own eyes what’s happening in these reservoirs. Further, the satellite imagery corroborates both Stimson’s virtual gauge estimates and the stories told by Eyes on Earth’s natural flow models at Chiang Saen, Thailand and Vientiane, Laos.

The monitor’s home page displays an interactive map showing the locations of the platform’s 31 virtual gauges which link to information about those gauges. The map also links to other data on physical gauges provided by the Mekong River Commission, Thailand’s EGAT, Laos’s EDL-Gen, and China’s Lancang Mekong Water Resources Center. When taken as a whole, this interactive map acts as a single window into water availability, river level, and major dam operations throughout the Mekong Basin.

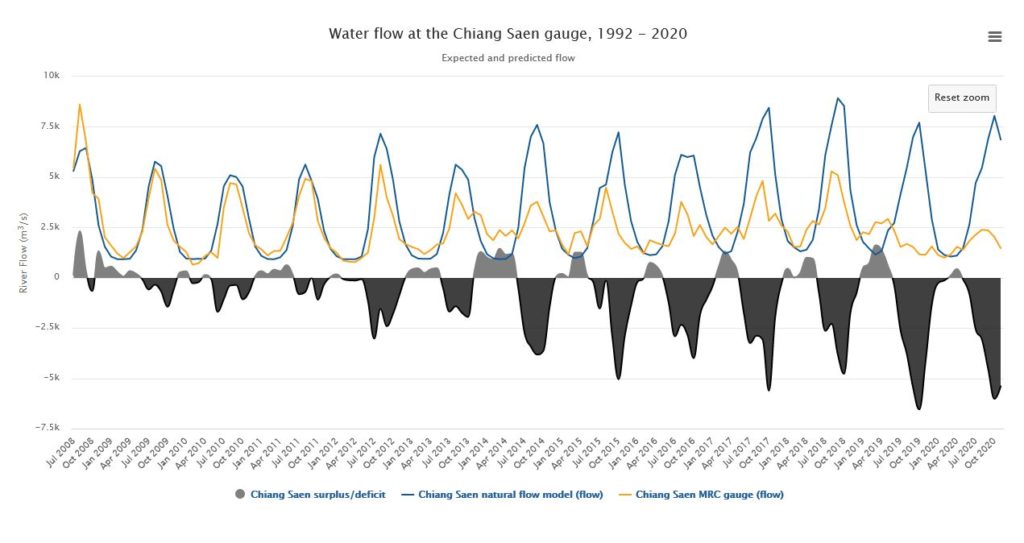

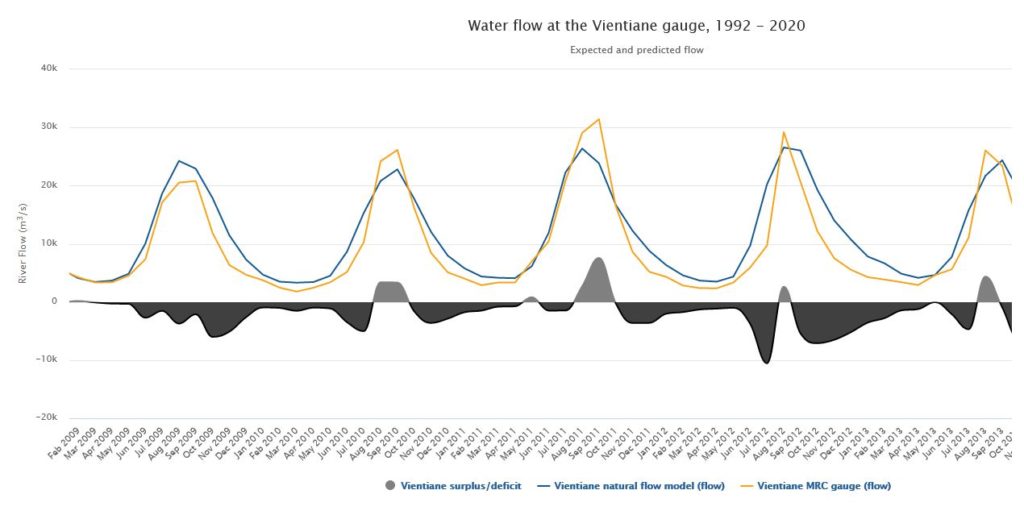

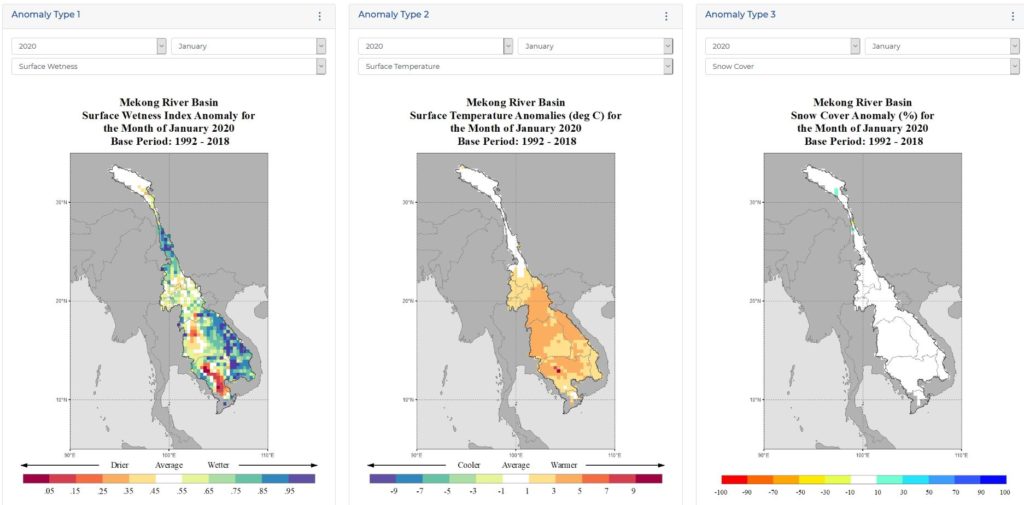

Eyes on Earth provides model-derived estimates of natural flow, which would occur if no dams were altering the rhythm of the river discharge. These results demonstrate how much water should be in the Mekong mainstream under natural conditions compared to the Mekong River Commission Gauge measurements at Chiang Saen, Thailand and Vientiane, Laos. The models use data collected through Eyes on Earth’s Wetness Index and Eyes on Earth calibrates their models through selecting years when the Mekong flowed with zero to minimal regulation from upstream dams. Calibrated during a period of time before major dams impacted the Mekong basin, the Chiang Saen model explains 90% of the variability in the river and the Vientiane model explains 87.5% of the river’s natural variability. The models show how the filling of the Nuozhadu reservoir in 2012 increasingly broke the river’s natural flow cycle all the way to Vientiane in the middle of the basin.

The previously unreleased natural flow model for Vientiane will also show how the addition of the Xayaburi dam in Laos and dams on tributaries such as the Nam Ou and Nam Khan rivers will further manipulate flow,” says Basist. Currently 15 dams are completed in Laos’s portion of the Mekong above Vientiane with more than 30 under construction or in development stages, according to data from the Mekong Infrastructure Tracker. Eyes on Earth’s Vientiane natural flow model will capture the impacts of all of these dams on the natural rhythm of the river.

The platform also includes maps and data showing how temperature, precipitation, and importantly snow cover is changing in the basin over time. Researchers can utilize this new data to produce findings on how the basin’s climate is changing. Eyes on Earth’s Wetness Index anomalies (which are available on the platform) also provides critically important information for agricultural planners and hydrological offices in Mekong governments.

Building on Collaboration

The Mekong Dam Monitor is supported by a grant from the U.S Department of State with additional support from Chino Cienega Foundation and individual donors. As part of the Mekong-U.S. Partnership, the Monitor builds on the ongoing work of the Mekong Water Data Initiative (MWDI) to improve the transboundary management of the Mekong River through data sharing and science-based decision making. The project’s total first year budget is $215,000.

The project team’s goal is to deliver a lean platform that can easily be transferred to the regional ownership in due time. Big steps toward data transparency and upstream accountability don’t have to cost much in terms of dollars. We believe upfront investment costs are orders of magnitudes lower than gains reaped from mitigation of downstream impacts or the extreme consequences and costs of mismanagement.

The project team leverages the expertise of a very qualified advisory board to govern and provide direction to the future of the platform’s development. The full list of advisory board members will be published on the Stimson center website on December 15, 2020. Further the project team seeks direct engagement with governments, NGOs and other parties in the regions to produce a quality product. The project team does not plan to lead this effort indefinitely. A core goal is to identify where there is support and resources to take eventual local ownership and maintain the platform in the future. Our medium-term plans are to identify and collaborate with various organizations like the Mekong River Commission to support this work and ongoing activities central to the operations and data delivery. This approach is expandable through the larger Mekong basin and other river basins around the world, where similar issues are evident.

To develop the platform, the project team held focus groups and consultations with government and non-government stakeholders active in the Mekong region. The team engaged the Mekong River Commission in an unofficial capacity, and this led to several key evolutions in the project’s development, namely a commitment to use open-source inputs and how to effectively validate indictors and data displayed on the platform. The project team provided notification to China’s Lancang-Mekong Water Resources Center and offered a consultation. At this time, we have not received a response. In the coming months, the project team will release local language versions of the platform in all six national languages of the Mekong: Vietnamese, Thai, Khmer, Lao, Burmese, and simplified Chinese. Additionally, we will release a smart phone application that will also allow users to communicate data and images to the project team. We welcome research partners, who can help us rapidly expand the scope of analysis to additional dams and cascades in the Mekong basin, as well as other basins around the world.