| Capital | Bangkok |

| Area | 513,120 km2 |

| Population | 69,799,978 (2021 est.) |

| GDP | USD 501.79 billion |

| GDP Growth Rate Projections | 0.8%% in 2021 due to COVID pandemic, usually around 4.0% annually pre-pandemic |

| Inequality (Gini Coefficient) | 34.9 (medium) |

| Human Development Index (HDI) | 0.777 |

| World Bank Income Status | Upper Middle Income |

| World Bank Ease of Doing Business Ranking | 21 out of 190 |

| Key export | Cars, computers, electrical appliances, rice, textiles, footwear, fishery products, rubber, jewelry |

Thailand’s national strategy proposes the development of high-quality infrastructure to connect Thailand to the world, solidifying its position as an economic hub of ASEAN and a major connecting point in Asia.

Thailand’s Infrastructure Gap

In the lower Mekong region, estimates of required investments vary greatly. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) estimates that the required investment level, for different regions of Asia, should be between 4.5 to 8.2 percent of GDP, and 5.2 to 9.1 percent if adjusted for the effects of climate change. The estimates for Southeast Asia for the base and climate-adjusted scenarios are 5.0 and 5.7 percent of GDP respectively.

For more than five decades, Japan has been Thailand’s largest source of total foreign direct investment (FDI). FDI from Japan reached USD 2.49 billion in 2019, a third of total FDI in Thailand. In 2018, Japan was also the largest bilateral donor of Official Development Finance (ODF) for infrastructure in Thailand, while the ADB was the largest multilateral donor. In 2019, however, China emerged as the frontrunner, overtaking Japan as Thailand’s primary source of FDI. FDI applications from China, valued at USD 8.6 billion, comprised nearly half of the total USD 16.7 billion FDI applications in 2019. A significant number of such proposals were linked to a high-speed rail project connecting Suvarnabhumi, Don Muang and U-Tapao airports, as well as the country’s Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC).

Energy Sector Overview

As of 2021, Thailand’s Ministry of Energy reports just over 46 GW of installed power generation capacity. Thailand has for years had near one hundred percent electrification and has the highest electricity use per capita in mainland Southeast Asia, which in 2020 hit 2,826 kWh per person1Energy Policy and Planning Office, Thailand Ministry of Energy, “Table 7.2-5: Electricity Consumption per Capita,” August 2021, accessible at http://www.eppo.go.th/index.php/en/en-energystatistics/energy-economy-static. The nation’s capital, Bangkok, is responsible for over 40 percent of total consumption.2Danny Marks, “Lao PDR foots the bill for power-hungry Bangkok,” Mekong Commons, December 11, 2014, at http://www.mekongcommons.org/Lao PDRfoots-bill-power-hungry-bangkok/.

The growth rate of electricity demand in Thailand is moderate, with an average annual rate of around four percent. Historically, the electricity system has been centrally designed at the national level to ensure the reliability of the electricity supply in Bangkok and has been dependent on point-to-point transmission from large commercial-scale power plants. However, a significant portion of this – 56%, or up to 20 GW—is excess capacity above and beyond what’s needed for peak demand. This high excess capacity highlights systemic inefficiencies and raises questions about the necessity of continued new power generation buildout in the short term. The 2020 coronavirus pandemic has spurred a decline in the rate of electricity use of 5.8% in 2020 during the COVID pandemic, and may continue to face low growth or even contraction until the pandemic ends due to lockdowns and economic impacts.3Yuthana Praiwan, “Eppo: Energy contraction set to persist,” The Bangkok Post, January 20, 2021, accessed Sept. 23, 2021, at https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/2053791/eppo-energy-contraction-set-to-persist. This has prompted the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand to reconsider future investments and take steps towards reducing reserve power generation capacity.

Current status of power generation

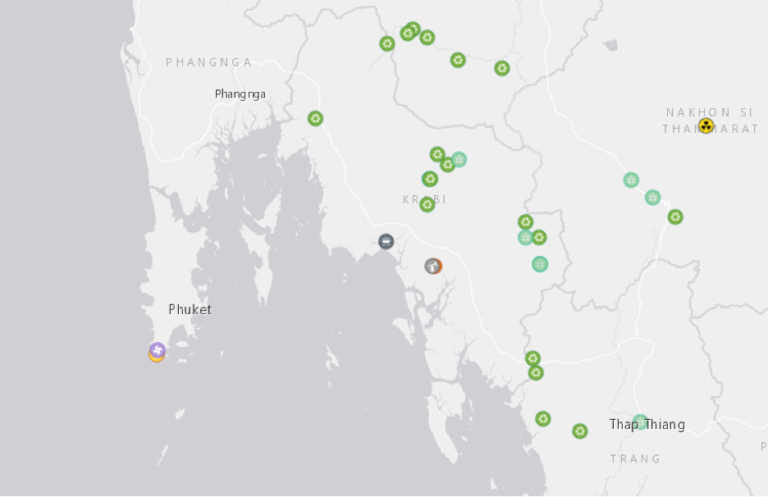

The Mekong Infrastructure Tracker shows project-level data for 286 operational power plants in Thailand as of 2021, as well as 172 projects of unclear status, 29 projects currently under construction, and 12 planned projects. The operational projects have an installed capacity of 44,065 MW, of which 70% is natural gas, 13% is coal, 9% is hydropower, and the remainder a mix of solar, wind, mixed fossil fuels, biomass, waste, oil, and geothermal power.

The most widely used fuel source in Thailand is natural gas, accounting for approximately seventy percent of the fuel mix, followed by coal at twenty percent.4Energy Policy and Planning Office, “Power Development Plan (PDP) 2018-2037”, translated from the Thai: “แผนพัฒนากำลังผลิตไฟฟ้าของประเทศไทย พ.ศ. 2561 – 2580″, Ministry of Energy, April 2019. Compared to its neighbors, Thailand’s share of hydroelectric generation is small, accounting for about nine percent of the total mix up against well over the power generation in Cambodia and Laos. However, Thailand also imports power from Laos, and as more planned hydropower projects in Lao PDR are approved and implemented, power imports will continue to increase. As of 2021, Thailand’s power imports totaled 5,720 MW of electricity.5Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand, “System Installed Generating Capacity,” EGAT, August 2021, accessible at https://www.egat.co.th/en/information/statistical-data?view=article&layout=edit&id=80. Most of this is from Laos with a portion (1473 MW) from the Hongsa Coal Plant and the remainder from hydroelectricity. As of April 2018, renewable energy supplied approximately 15% of Thailand’s energy capacity, and 10% of the country’s electricity is generated by renewables. Given Thai lawmakers’ cognizance of the country’s high excess capacity, the country is looking to export power, and currently exports a small amount to Lao PDR, Cambodia and Malaysia.6Ricardo Energy & Environment.

Thailand’s most recent Power Development Plan (PDP), released in 2018, outlines plans for the country’s energy landscape from 2018 to 2037, setting a target of 56,431 MW of new power generating capacity, of which thirty-seven percent will be from renewable energy projects. Driven by the rapidly increasing prominence of renewable energy, by 2037, the country’s production mix is expected to be 53% natural gas, 35% non-fossil fuels, and 12% coal.7Energy Policy and Planning Office, “Power Development Plan (PDP) 2018-2037”, translated from the Thai: “แผนพัฒนากำลังผลิตไฟฟ้าของประเทศไทย พ.ศ. 2561 – 2580″, Ministry of Energy, April 2019. Solar energy accounted for 3300 MW of electricity production in Thailand as of 2018, and the country is taking tangible steps to realize the 2018 PDP’s goal of 12,725 MW of solar capacity and 1485 MW of wind capacity, including investment in electricity storage technologies such as lithium ion batteries and hydrogen fuel cells.8Weatherby, C., Eyler, B. ,Schmitt, R., Avila, N. and Harou, J; “Thailand’s Energy Development Pathways: An exploration of risks, costs, and benefits for different import scenarios”, Lower Mekong Initiative (LMI)-Sustainable Infrastructure Partnership (SIP), Bangkok, Thailand, September 2020, page 12. Moreover, agriculture’s major role in Thailand’s economy has foregrounded biomass as a significant renewable energy source: the country had approximately 3000 MW of biomass installed as of 2019.9Weatherby, Eyler, Schmitt, Avila, and Harou, page 12.

Prominent Project Snapshot: Krabi Power Plant

| Project Name | Krabi Power Plant |

| Subtype | Coal |

| Current Status | Suspended/Postponded |

| Capacity (MW) | 800 |

| Year of Completion | 2019 (now delayed due to pandemic) |

| Country of Sponsor/Developer | Thailand |

| Sponsor/Developer Company | EGAT (Thailand) |

| Country list of Construction/EPC | Thailand; Italy; China |

| Construction Company/EPC Participant | Italian Thai Development Plc (Thailand); Power Construction Corporation of China (China) |

| Country | Thailand |

| Province/State | Krabi |

| District | Muang Krabi |

| Watershed | Coastal Rivers Krabi-Phukhet-Phangnga |

| Latitude | 8.059167 |

| Longitude | 98.91889 |

While coal occupies only 18% of the Thai energy fuel mix, domestic policymakers have clearly stated that coal is viewed as a key portion of the national energy portfolio as it has proved successful in fulfilling short term increases in energy demand. Energy demand in the south of Thailand has grown faster than the rest of the country at rates of 5-6% annually due to economic development in the service and tourism sectors.10Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand, “Why does the South of Thailand need coal -fired power plants?” Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand, 2018, https://www.egat.co.th/en/news-announcement/egat-reasons-why/why-does-the-south-of-thailand-need-coal-fired-power-plants. This energy demand is currently met through transmission lines from plants in central Thailand, raising questions about costs and reliability; regular blackouts became increasingly frequent as demand rose.11Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand. EGAT used this lack of reliability to justify its push for more coal-fired power plants in the South, a means of boosting local energy autonomy and security.

In recent years, planned coal projects have raised concerns over potential environmental and health impacts and new coal projects in Thailand have faced public resistance on multiple occasions. Most recently, a planned 800 MW coal plant in the southern province of Krabi was met with vehement public opposition due to possible adverse effects on beach tourism and the local environment. Tourism-reliant local communities voiced their support for sustainable tourism and clean energy, while groups such as fishermen lamented the potential ecological impacts that would upend their ways of life.12Apinya Wipatayotin and Taam Yingcharoen, “Protestors rejoice after coal ‘victory’,” Bangkok Post, February 21, 2018, https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/1415079/protesters-rejoice-after-coal-victory. In response to these protests, which had spanned almost four years since beginning in 2013, on February 28, 2017, Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-Ocha halted the project and demanded that the Electricity Generating Project of Thailand (EGAT) conduct a further environmental and health impact assessments. The process was slated to take two years, and in March 2020 the final decisions were postponed once again due to the COVID-19 pandemic.13Wipatayotin and Yingcharoen. While there has not been an official cancellation notification for the project, in July 2021 the Governor of the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand indicated that this controversial project and the Songkhla Coal Plant are likely to be replaced with a natural gas plant.14Yuthana Praiwan, “Gas-fired plant to get the nod,” Bangkok Post, July 21, 2021, accessed Sept. 23, 2021, at https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/2152099/gas-fired-plant-to-get-the-nod.

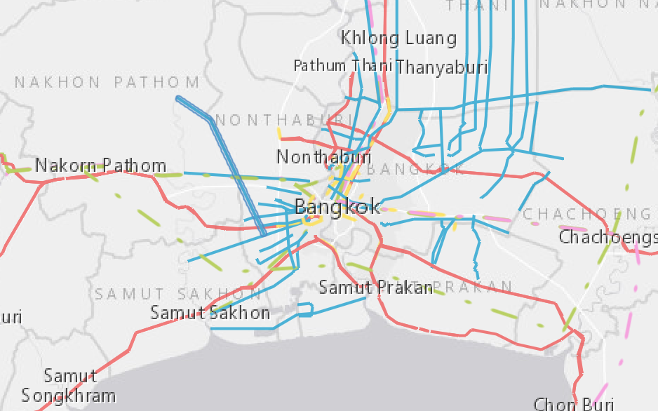

Transmission Lines

The Mekong Infrastructure Tracker has detailed data on 586 operational transmission lines in Thailand, of which 317 are 115 kV, 216 are 230 kV, and 53 are ultra-high-voltage 500 kV. There are also plans to expand the network, with 87 additional transmission lines under construction and 72 in planning stages. Transmission line expansions have been in progress over the last decade, with three key purposes. First is to meet increasing electricity demand, especially in the Greater Bangkok Area and other urban environments. Second is to enhance linkages between different regions inside Thailand, improving system security around the country and preparing for integration of higher amounts of electricity from renewable energy. The third priority is to augment regional grid connectivity with neighboring countries and facilitate power purchases, especially from Lao PDR.15Thailand Power Development Plan 2015-2036, https://www.egat.co.th/en/images/about-egat/PDP2015_Eng.pdf; Thailand Power Development Plan 2018, Thailand has a long-term goal of becoming a regional electricity trading hub, and improved connectivity both domestically and with all neighbors—Laos, Cambodia, Myanmar, and Malaysia—will be important for facilitating future electricity trade.

Physical Connectivity Overview

Thailand’s central location in mainland Southeast Asia positions it as a regional economic and cultural nexus, effectively serving the region’s financial, manufacturing, tourism and service needs. Infrastructure spending has continued to rise in recent years following a decline after the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis. Despite this, the quality of transport and logistical infrastructure is still insufficient to fully realize the country’s potential as a regional hub.

Thailand’s road network is the most extensive in Southeast Asia, with a total length of 390,026 km, 98% of which is concrete or asphalt paved. This translates into 47,916 km of rural roads and 352,157 km of local roads. An extensive network of highways connects the country’s major cities to one other and to the transnational Asian Highway. Thailand’s Infrastructure Development Plan (2015-2022) proposes a series of four-lane road networks to link the country’s key economic regions and border areas.16Thailand Board of Investment (BOI), “Highways”, BOI, retrieved on 7 October 2020, https://www.boi.go.th/index.php?page=highways An Intercity Motorway Development Master Plan (2017 – 2036) also sets a target of 6,612 km of motorway routes in order to meet increased demand for road transport and ensure safety. Road safety continues to be a pressing issue, as Thailand has the world’s second highest road fatality rate.

Thailand’s 4,034 or single, double and triple-tracked rail networks suffer from significant underinvestment, and account for a mere 3.7% of travel mode share. The Asian Development Bank predicts that without intervention, rail may fall into complete disuse within a decade.17Asian Development Bank (ADB), “Thailand Industrialization and Economic Catch-Up”, ADB, retrieved on 5 October 2020, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/178077/tha-industrialization-econ-highlights.pdf The State Railway of Thailand (SRT), while one of the largest state-owned enterprises, is perceived by the Thai public as inefficient and resistant to change. All attempts by the government to restructure or privatize the company have been met with opposition by the union, and this has hindered investment efforts.18Penchan Charoensuthipan, “Back to the railway future?”, Bangkok Post, 27 July 2019, retrieved 7 October 2020 at https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/special-reports/1719855/back-to-the-railway-future-. To further facilitate the development of connectivity infrastructure, Thailand’s Office of Transport and Traffic Policy Planning (OTP) announced a comprehensive 20-year plan to improve connectivity. The plan calls for the development of double-track, meter-gauge, and standard-gauge rail routes for high speed trains, all with planned lengths of over 2000km respectively, in addition to expanding container storage capacity and the use of electric trains.19Bangkok Post, “OTP unveils 20-year master rail plan”, Bangkok Post, retrieved on 21 August 2020, https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/1329707/otp-unveils-20-year-master-rail-plan.

Prominent Project Snapshot: Nong-Khai Thanaleng Railway

| Project Name | Nong Khai-Thanaleng |

| Subtype | Railway |

| Current Status | Operational |

| Length (km) | 7.35344761 |

| Country | Laos; Thailand |

| State or Province | Vientiane [prefecture]; Nong Khai |

| District | Hadxaifong; Xaysetha; Muang Nong Khai |

| Main Basin | Mekong-Lancang |

| Tributary | Mekong Mainstream - Lower |

| Links | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Template:SRT_Northeastern_Line_route_map |

The Nong Khai–Thanaleng railway link is an international railway link that connects Nong Khai Province, Thailand with Vientiane Prefecture, Laos. It began operations on 5th March 2009.20Andrew Spooner, “First Train to Laos”, The Guaedian, retrieved 7 October 2020 at https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2009/feb/26/first-train-laos-thailand-rail. A USD 6.2 million project financed primarily by Thai loans, the link provides the Laotian capital Vientiane connections with three other major ASEAN capitals: Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur and Singapore.21Spooner, “First Train to Laos.”

Industrial Zones

Sustained high growth and a rapid decline in poverty allowed Thailand to join the ranks of upper-middle-income countries in 2011. From 1987 to 1996, GDP grew at an average of 9.5% per year, fueled by business-friendly regulations, high domestic demand, and open access to foreign direct investment.22Asian Development Bank (ADB), “Thailand Industrialization and Economic Catch-Up”, ADB, retrieved on 5 October 2020, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/178077/tha-industrialization-econ-highlights.pdf Following the Asian financial crisis of 1997-1998 and the ensuing years of political instability, growth slowed to an average of 3.9% between 2000–2014.23ADB, “Thailand Industrialization and Economic Catch-Up.” The impact of political turbulence is reflected in the historical World Bank Ease of Doing Business Rankings, in which following the 2014 coup, Thailand’s rank dropped from 18 to 46 out of 190. However, the country has since started to recover and was ranked 21 out of 190 in 2019.24World Bank, “Ease of Doing Business Index,” retrieved at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IC.BUS.EASE.XQ While Thailand has largely been successful in transitioning from a primarily agrarian to a primarily export-oriented manufacturing economy, productivity must keep pace with rising wages to maintain economic competitiveness. Low-productivity jobs in the trading and services sectors continue to constitute a large share of the workforce, and the agricultural sector still accounts for 40% of the labor force. Export competitiveness has also been largely stagnant as newer players have entered the global market. Moreover, growth and development have largely been centered around Bangkok and its surrounds, while the rest of the country lags far behind in industrial and social development.25ADB, “Thailand Industrialization and Economic Catch-Up.”

While there are 42 industrial zones and 9 Special Economic Zones around the country, the Thai government has also supported the development of a large-scale export-oriented industrial zone along the country’s eastern seaboard spanning Chacheongsao, Chonburi and Rayong provinces that is known as the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC).26Eastern Economic Corridor Office (EECO), “PPE EEC Track”, EECO, retrieved on 7 October 2020, https://www.eeco.or.th/en/eec-ppp-track The EEC covers 13,000 square kilometers and is at the center of the government’s initiatives to support and accelerate growth in public utilities, transportation systems, human resources and foreign investment. To finance the infrastructure investment gap, the government has also actively supported contributions from the country’s private sector; public private partnerships (PPP) are a preferred source of financing the development of infrastructure, especially in the EEC).27EECO, “PPE EEC Track.”

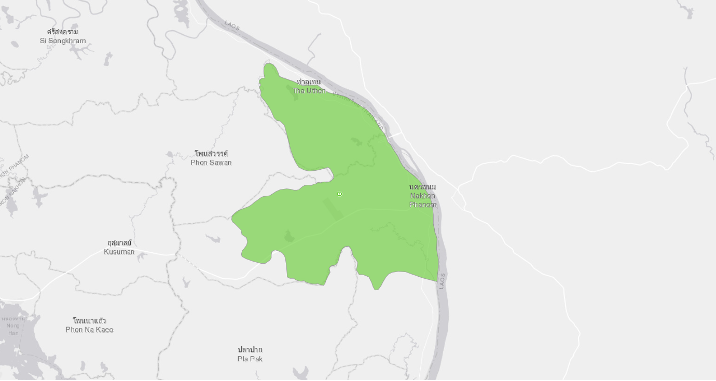

Prominent Industrial Zone Snapshot: Nakhon Panom Special Economic Zone

| Project Development Cycle Stage | Under Development; Phase II |

| Area (km2) | 627 km2 |

| Country of Sponsor/Developer: | Thailand |

| State or Province | Nakhon Phanom |

| District | Muang Nakhon Phanom; Phon Sawan; Pla Pak; Tha Uthen |

| Main River Basin | Mekong-Lancang |

| Tributary | Mekong Mainstream - Lower |

| Data Source | Board of Investment of Thailand |

The Asian Development bank (ADB) first introduced the prospect of developing SEZs (Special Economic Zones) along the border regions of Thailand in 1998, as a means for promoting the use of transboundary economic corridors. This later led to Thailand formulating Border Economic Development Action Plans to transform existing transportation corridors in the region into full-fledged economic corridors. In 2014, the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) of Thailand announced a new policy on Special Economic Zones as a way of stimulating economic productivity in border areas and fostering transnational connections between cities in ASEAN. After this, the NCPO issued Order 72.2014 to enumerate the functions of a Special Economic Development Zone Policy Committee. Six sub-committees were also established under this order to take responsibility for various portfolios at regional and national levels.

In 2019, Thailand’s Special Economic Development Zone Policy Committee, under the chairmanship of Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-Ocha, endorsed the selection of JCK International, an industrial development firm, to head the development of the SEZ in Nakhon Phanom province. Spanning 627 km2 near the third Thai-Lao friendship bridge, the SEZ will serve as a commercial mixed-use project with a hotel, healthcare center, trade exhibition center, sports complex and other such facilities.

Reservoirs

Among the 167 reservoirs shown by the Mekong Infrastructure Tracker, 24 reservoirs store water for hydropower use, 142 reservoirs serve as water supply, and one reservoir is designed for mixed-use. In terms of surface area, the hydropower reservoirs cover 2307 square kilometers, doubling the surface area of water supply reservoirs, which only cover 916 square kilometers of land.