Good morning, Chair Ami Bera, Ranking Member Steve Chabot, and members of the Subcommittee. I am Brian Eyler, director of the Stimson Center’s Southeast Asia Program. Thank you for the opportunity to provide a testimony which highlights how the Mekong River guarantees the security and livelihoods of tens of millions of people in mainland Southeast Asia and why a smarter engagement strategy from the US can keep the Mekong region thriving. Today I will describe a range of security challenges currently unfolding in the Mekong region. I will then outline how the US can deepen its record of foreign policy engagement with strategic and pragmatic support to our friends and partners in the Mekong.

My testimony draws on two decades of work with communities, planners, and researchers in the Mekong, much of which is summarized in my book Last Days of the Mighty Mekong (2019), and six years of impactful policy work at the Stimson Center. My team has long played an informal advisory role first to the US Department of State’s Lower Mekong Initiative (LMI) and now the rebranded Mekong-U.S. Partnership (MUSP). My team currently implements two of the MUSP’s key projects won through competitive grant processes: The Mekong Dam Monitor and the Mekong-U.S. Partnership Track 1.5 Dialogues. The Mekong Dam Monitor launched in late 2020 and uses satellites and social media to inform vulnerable communities and governments in the Mekong about the impacts of upstream dams. This project provides unprecedented transparency over the operations of upstream dams – two of the largest of which are in China – and provides vulnerable downstream countries and communities with the information they need to plan to mitigate sudden floods and water and food crises. Below, I will return to the positive benefits the Mekong Dam Monitor has generated since launch.

The other project my team manages is the Mekong-U.S. Partnership Track 1.5 Dialogues, a series of interactive conferences which bring together government and non-government stakeholders from the Mekong region and from key development partners like the US, Australia, Japan, Korea, India, and the EU. These dialogues have thematic focuses on energy & infrastructure, connectivity, human resource development, nature-based solutions, illicit trafficking, and transboundary water management. At these dialogues, participants work together to identify challenges facing the Mekong region and develop policy and development solutions to address these challenges. I have seen the positive results of these dialogues reflected in new programming from the executive branch, the most recent of which were announced during Vice President Kamala Harris’s November 2022 visit to Thailand. These dialogues represent a bottom-up, inclusive platform where local stakeholders can articulate needs and develop solutions. Like most of the projects the US implements in the Mekong, the Mekong-U.S. Partnership Track 1.5 Policy Dialogues create local capacity and promote knowledge sharing in the region, something the PRC’s foreign policy in the region does not do.

To focus back to the Mekong, I would like to highlight a few points which underscore why the river and the region are important for US engagement.

- First, the Mekong is the world’s 12th longest river. Half of its length is in China while the other half passes through parts of Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Being home to the Mekong’s headwaters and half of its length makes the PRC an upstream riparian which can and has, through the non-transparent operations of 11 of the world’s largest dams, wielded outsized influence over water and food security outcomes in the downstream. To date the PRC has not shared data with downstream countries on how those dams are operated. The PRC does not have the courtesy to inform the downstream of when dams begin construction or start operations. Below I will discuss how sudden releases from PRC dams have caused flash floods and how their flow restrictions have exacerbated drought in the downstream.

- Most of the territory of Lao PDR and the Kingdom of Cambodia falls within the Mekong Basin. The economic security and food security of these countries are heavily dependent on the natural resource base provided by the Mekong’s seasonal hydrological changes. Laos and Cambodia are the most vulnerable to what their neighbors do to the river system, whether that is building dams which alter the Mekong’s natural flow, removing sand and sediment from the river for industrial and urban development, or polluting the river with plastics and industrial waste. And to be clear, Lao PDR and Cambodia are simultaneously affected by and among the poorest practitioners of these harmful practices. Laos has 100 Mekong dams locked into its future as it vies to be the “Battery of Southeast Asia” and sell hydropower for export to its surrounding neighbors. China, Thailand, Vietnam, and other foreign investors are lining up to dam Laos’s numerous tributaries at a pace which most scientists and researchers suggest will bring ruin to the Mekong’s natural resource base. In 2018, China’s Huaneng Power Company built the worst sited dam in the entire Mekong basin, blocking two critical tributaries in northern Cambodia.

- To highlight the Mekong’s robust natural resource base, my testimony turns to Vietnam’s Mekong Delta, a landscape the size of West Virginia upon which nearly 20 million people, 20% of Vietnam’s population, live. Farmers there rely on the waters of the Mekong to produce most of Vietnam’s annual rice product, more than half of which is exported to Southeast Asia and the rest of the world. Vietnam is currently the world’s second highest exporter of rice. The Mekong Delta is both a food security guarantor and an income generator for Vietnam. Yet the Mekong Delta and its economic productivity are threatened by the triple challenge of rising seas, upstream dams which hold back water and sediment during times of need, and outdated economic practices set decades ago in what was then a very different Vietnam from today.

- And finally, my testimony turns to the Mekong’s most unique feature, Cambodia’s Tonle Sap Lake, which is Southeast Asia’s largest lake and alone is responsible for much of the Mekong’s mighty bounty. According to the Mekong River Commission, the ecology of this lake serves as the bellwether for the health of the entire Mekong basin. Up until recent years, the lake would like clockwork expand five times its size during the wet season months of June to October as it takes on water from the Mekong mainstream. This incredible phenomenon happens when the river which typically drains out of the lake reverses course. When the wet season waters rush into the lake, so do fish, sediment, and organic material which combine to provide the energy to create a massive explosion of life in and around the lake. This lake alone typically provides 500,000 tons of capture fisheries annually to the people of Cambodia, making up 60-70% of their animal protein intake, another food security guarantor. And when the lake contracts from December to May of each year, hundreds of species of fish migrate out of the lake to spawn upstream. This is the largest migration of animals on the planet, greater in magnitude than the Great Serengeti migration. This migration is the keystone of the Mekong’s impressive 2.6 million annual ton freshwater capture fishery (inclusive of all Mekong countries), a figure which is 13 times more than the size of freshwater capture fishery of all of North America’s lakes and rivers combined. To translate this into global importance, the Mekong produces 20% of the world’s freshwater fish catch. A changing climate, upstream dams, and IUU fishing on the lake put its fish population gravely at risk. If it collapses, I and many other Mekong researchers predict that the security of Cambodia and much of the Mekong region will come undone.

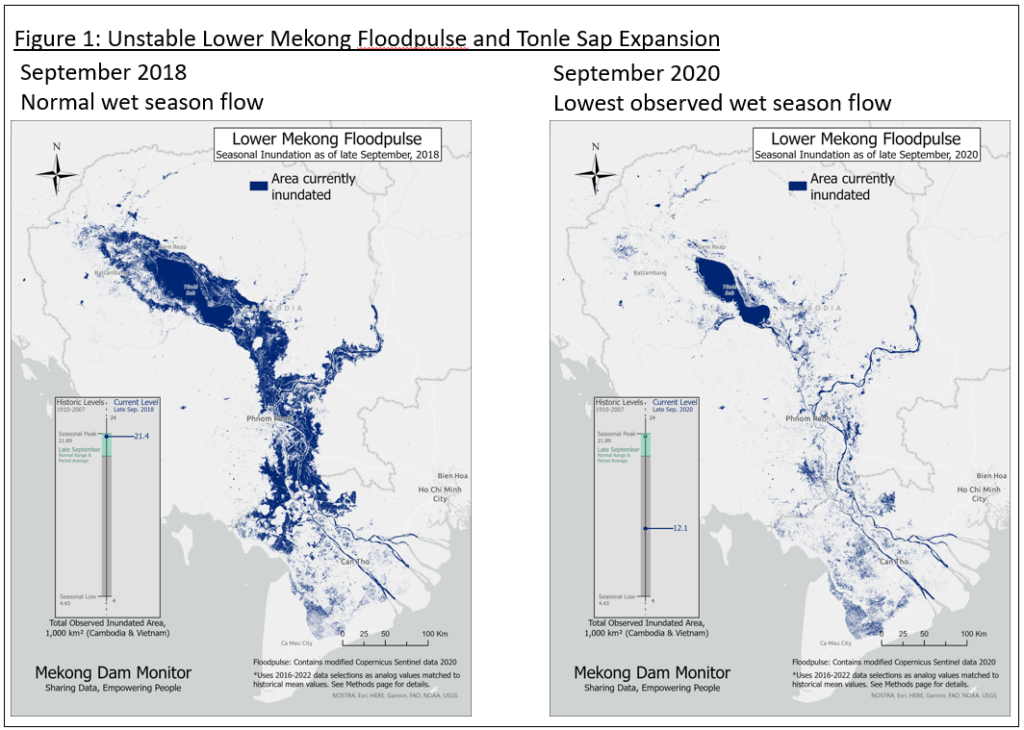

Figure 1 below shows how the Tonle Sap flood pulse is changing. The map on the left shows the Tonle Sap near maximum expansion in September of 2018, which represented a typical pattern of wet season precipitation. The map on the right shows the Tonle Sap expansion during September 2020, the lowest wet season flow year in more than 100 years of record keeping. In 2020, the Mekong’s flood pulse was absent, and the lake simply did not expand. Official records showed a 30% decline in the lake’s fish production, but local fishers reported up to 70% decline in fish catches. This pattern was also present during 2019 and 2021 through the hardest parts of the pandemic. While the major driver of low wet season flow was related to climate, upstream dams significantly exacerbated these conditions.

From here, I would like to further focus on the river and the region’s most critical problems. I will outline pathways through which the US can strategically engage the governments and peoples of the Mekong Region to mitigate environmental and natural resource base challenges, promote inclusive and sustainable development, and work with partners to provide new solutions to current suboptimal practices and maligned influences in the region.

- Increase science and transparency activities: As I mentioned previously, the PRC does not share information on the storage status of its 11 dams, nor does the PRC provide information on how those dams are operated. Downstream countries have long speculated that upstream dams are restricting flow and are responsible for a weakening of wet season flow. Downstream communities have also suffered sudden floods during periods when there was no extreme weather event and speculated these floods were caused by sudden releases from dams in China. The worst of these happened without warning in 2013 when the river suddenly raised 4 meters overnight, flooding communities in Thailand and Laos and causing millions in damage. Data produced by the climate consultancy Eyes on Earth suggest this flood was caused by a sudden release of water from China’s Nuozhadu Dam, which is the largest on the Mekong.

- Today, the Mekong Dam Monitor, which is co-led by my team and Eyes on Earth, uses satellite derived data to watch China’s dams and provide downstream communities with 2-5 days of early warning prior to the impact of those sudden releases, giving them precious time to adapt. Since 2020 we have issued 53 early warnings to vulnerable communities via social media and through the Thai government’s disaster risk reduction agencies. Because of the evidence we deliver, the Thai government has sent numerous letters of concern to Beijing asking for prompt early warning when China’s dams suddenly release or restrict flow. The Mekong Dam Monitor also has established that China’s two largest dams hold 50% of the total active storage of the 45 largest dams in the Mekong. Figure 2 below demonstrates that during the severe wet season droughts of 2020, those dams alone reduced total wet season flow to Cambodia far downstream by an estimated 9.3%, significantly impacting the potential expansion of the Tonle Sap. Farther upstream along the Thai-Lao border, those dams reduced total wet season flow by an estimated 63%.

Figure 2: During Wet seasons which are anomalously dry, China’s dams have greater negative impacts

The Mekong Dam Monitor offers unprecedented transparency in near-real time over the operations and impacts of the largest dams in the region. This data is used by the Mekong River Commission to understand how dams change the ecology of the river and gives downstream riparians a fighting chance to preserve the natural resource base of the Mekong and negotiate a more equitable share of water, particularly during times of need. The Mekong Dam Monitor also publishes its outputs in seven languages on its platform. In 2022, these outputs have reached more than 15 million social media accounts, most of which was in the region. The Mekong River Commission has long made calls to the United States and development partners for improved capacity which use remote sensing tools and sophisticated, scientific efforts on to produce early warning, drought and flood forecasting. Because of the transparency they provide and the partnerships these projects build, the U.S. government should provide sustained funding to the Mekong Dam Monitor, other projects supported by the State Department’s Mekong Water Data Initiative, and USAID SERVIR-Mekong.

- Increase support to the Mekong River Commission: The Mekong River Commission was established in 1995 by international agreement by member countries Thailand, Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. The MRC is the only treaty-based regional body with a clear mandate and functions for transboundary river management. I have observed the MRC become more active in communicating about the Mekong challenges and the need for actions over the last seven years. The MRC has established rules for water utilization and a strong knowledge base, including effective and sometimes informal use of partners’ work such as Mekong Dam Monitor to move things forward. The MRC has a working relationship with China and its Lancang-Mekong Cooperation Mechanism (LMC), and the MRC keeps riparian countries working together despite different interests on major issues like dams. The MRC and the LMC share little common interest in how the Mekong River’s resources are used. The MRC’s discourse states clearly that the annual Tonle Sap expansion is the bellwether for the health of the Mekong system. For a healthy Tonle Sap, the dry season low levels are as important as high floods in the wet season. Yet, China’s LMC discourse has stated ad nauseum that wet season flood reductions caused by its dams restricting flow are beneficial to the downstream. And the Chinese claim their flow releases relieve drought in the dry season. These are opposing discourses. The MRC feels the weight of the upstream giant above them, so U.S. engagement is critical for the downstream countries and regional organizations like the MRC also in this regard. The upcoming 4th MRC summit in April 2023 could be an opportunity to make a strong sign of American commitment to the Mekong.

- Counter the PRC’s disinformation and influence over U.S. actions in the Mekong: The U.S. efforts in the Mekong have compelled China’s behavior for the better, and with the transparency delivered by the Mekong Dam Monitor among other efforts, I believe it is only a matter of time before China shares robust information on dam operations with downstream countries. Yet changing China’s behavior comes at a cost: our team and other similar efforts which call for increased accountability from the PRC have been the target of intense smear campaigns sponsored by the PRC’s state propaganda machine which utilizes state media outlets and academic institutions to attempt to discredit our efforts. The most contemptible disinformation effort appeared in May 2022 when, according to our own investigation, the PRC set up the Global Critical Research Center (GCRC), a bogus think tank claiming to be registered in Portland, Oregon and used the fabricated identities of American experts to discredit the Mekong Dam Monitor via a so-called joint study. The PRC then republished the GCRC’s joint study results in state media outlets in June, and these articles were syndicated in PRC-friendly media outlets around Southeast Asia.

- We are not fazed by these efforts, but these targeted misinformation and disinformation campaigns are becoming more sophisticated and need to be countered. The State Department’s Global Engagement Center (GEC) would be better positioned to counter these and similar misinformation campaigns if it had more dedicated resources allocated to the Mekong region. Additionally, the State Department has a track record of local journalism capacity building programs through IVLP, East-West Center, and the Earth Journalism Network, the footprint of which should be deepened by more and longer-term resources. As a Mekong researcher, I often find some of the hardest to answer questions are uncovered by investigative journalists employed by RFA, VOA, and VOD. These agencies too can produce more investigative work and better inform the people of the Mekong with more dedicated resources.

- I would also like to bring attention to another related issue involving US-based non-profits registered to do business in China but which also work in the Mekong. Through explicit and implicit means, the PRC interferes in the ability of these organizations to achieve impact with their US-funded Mekong work. These organizations avoid engaging on critical issues in the Mekong due to perceived sensitivities, or they censor themselves or actively seek to censor the work of their partners and subcontractors in the interest of maintaining good ties with Beijing. There is a real urgency to move strategically and pragmatically in the Mekong region. Interference from Beijing stalls the ability of some of the largest implementing organizations of US foreign policy projects to make decisive impact.

- Increase efforts to conserve and protect the Tonle Sap Lake and Mekong Delta: Vietnam and Cambodia are the two countries which stand to lose the most as the Mekong’s ecosystem unravels as a result of ill-conceived human interactions and from climate change impacts, yet both countries are committed to tackling this dual challenge head-on. Vietnam’s Resolution 120, promulgated in 2018, fully dedicates the Mekong Delta to a climate-resilient transition that brings Nature-based solutions for high value agriculture and builds capacity for millions of urban and rural people in the delta to live and adapt to sea level rise. In the Mekong Delta, the US Geological Survey, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF) are all implementing partners actively working to support Vietnam’s implementation of Resolution 120.

- In 2022, relevant ministries in Cambodia have joined hands in an interagency effort to conserve and protect the Tonle Sap. This includes the enforcement of IUU fishing, increased capacity for community-based fish conservation programs, and stricter land use regulations around the lake. These issues fit squarely in the US’s wheelhouse for deepened engagement, and in fact, several efforts are already underfoot. You might remember the news story from June 2022 of the catch and release of the world’s largest freshwater fish, a 661-pound Mekong Giant Stingray. The USAID Wonders of the Mekong team led by researchers from University of Nevada-Reno was behind that biodiversity find of the century and is working with agencies and communities in Cambodia to promote sustainability of the Tonle Sap, despite significant challenges related to working in Cambodia. The USAID Wonders of the Mekong project is a champion example of on-the-ground U.S. efforts in the region, and yet its funding cycle could end this year without renewed support.

- Promote the effective impacts of NGOs and civil society organizations: I will attest that overall, non-government organizations and civil society groups in the Mekong are much more in tune with how livelihoods and the environment are changing in the Mekong than government agencies. These organizations are often the only support mechanism to represent the needs of victims of sudden floods, of hundreds of thousands of villagers relocated from hydropower projects, or communities which have lost their core livelihood due to changes in the natural resource base. By and large, they also represent the diverse ethnic cultures of the Mekong and the needs of women and girls. At the same time, NGOs and civil society organizations often are solution-oriented and can forge breakthroughs on critical issues. A case in point is the work of the Chiang Khong Conservation Group in northern Thailand. In 2020, after nearly two decades of organized effort, this community-based organization successfully stopped Chinese engineers from blasting river rapids along Thai-Lao border which otherwise would have paved the way for the passage of large ships from China deep into downstream portions of the river. Their leader Mr. Niwat Roykaew was awarded the 2022 Goldman Environmental Prize for his efforts. While Niwat Roykaew’s dedication to conservation has shown how community-based organizations can achieve impact while facing considerable odds, his level of success is exceptional in the Mekong. Civil society groups face increasing pressure from governments and powerful interest groups. Advocates and activists in all of the Mekong countries have been jailed or face persecution. In the worst cases, sustainability and civil society champions have been disappeared or killed such as in the 2012 disappearance of Mr. Sombath Somphone, a charismatic and non-controversial sustainability advocate from the Lao PDR. The United States and development partners can continue to communicate the importance of inclusive, multi-stakeholder processes in the Mekong and the protection of individual rights and the rights to advocate for marginalized people and the environment.

- One way to move the needle forward on civil society participation is to build capacity within the Mekong River Commission to convene civil society and community-based stakeholders in its consultative protocols around hydropower development. To date, the consultative protocols which provide space for impacted peoples to voice concern are broadly viewed by civil society groups as a rubber stamp mechanism which does not represent or hear their concerns. The MRC lacks the resources to hold a sufficient number of consultations and is often unwilling to engage with environmental activists who are critical of the process. Local communities feel these consultation protocols do not provide avenues through which communities can influence decision-making or seek compensation for the transboundary impacts of hydropower development. U.S.-funded projects implemented by non-government organizations and U.S. agencies such as the Mississippi River Commission can engage the MRC in capacity building to develop better public participation processes by sharing best practices from the US, incorporating principles from the principles of Free, Prior and Informed Consent, facilitating deeper engagement with civil society, and providing resources to address some of the problems above.

- Strategically engage the energy sector to reduce pressures on the Mekong and provide opportunities for US companies: The Mekong region anticipates rapidly rising electricity demand in coming decades, and this push for power is a key driver of dam construction on the Mekong. However, hydropower is just one of many competitive energy sources. The Mekong countries have vast untapped non-hydropower energy resources, and support for alternative solar and wind can simultaneously help meet climate commitments by replacing fossil fuels and also reduce pressure for new dams. Electricity trade between Laos and other countries in ASEAN is a part of the future, and the United States can share lessons learned from inter-regional electricity trade and support strategic investment and power purchasing to ensure that rising demand in places like Ho Chi Minh City, Bangkok, and Singapore supports clean energy developments rather than new coal or large-scale dams. A combination of support for the clean energy transition—particularly solar and wind—could help the region meet its energy needs while conserving the river’s natural bounty and protecting regional food security.

- The U.S. can support the Mekong River Commission in building out an energy planning unit which can consider non-hydropower alternatives to dams as a way to minimize impacts and improve transboundary water and resource governance. The U.S. could support a collaborative system-scale study with the MRC which makes use of modeling advancements, improved data access, and considers impacts across multiple sectors to identify project portfolios which minimize impacts to the Mekong River. Capacity-building opportunities can share lessons learned by the U.S. with our own grid integration of solar and wind and adoption of flexible financial models to support the rollout of rooftop and grid-scale solar and wind with battery systems built in.

- Further, the region is ripe for strategic engagement in the Mekong’s energy sector by US investors: the ground has already been laid through existing programming under Asia EDGE, the Japan-US Mekong Power Partnership, and long-running initiatives on capacity building and policy. What is currently lacking is a flagship power generation project that the U.S. can point to as an example of our partnership in the region and public support for pilot projects for emerging technologies such as battery energy storage systems which can act as scalable proof of concept. There is a clear window of opportunity for the U.S. Development Finance Corporation to support investment in in clean power generation projects, energy storage, or strategically selected transmission lines to act as pilot projects and support flexible and forward-looking renewable electricity production and trade around the region. Down the road, opportunities for investment in nuclear technologies like advanced small and modular nuclear reactors could emerge with opportunities to support capacity-building in this space as well.

There are many other causes for concern and needs for deepened U.S. engagement in the Mekong region. Special Economic Zones in Laos and Cambodia are hotbeds for illegal activity including human, drug, and wildlife trafficking. Investigative journalists active in Cambodia have identified scam compounds which have kidnapped thousands of foreign nationals and subject them to human rights abuses. The region is victim to a massive unregulated and illegal extraction of natural resources ranging from deforestation to sand-mining to IUU fishing. Some of this activity is promoted by elements with roots in the PRC, and some is not. Yet tackling these difficult issues head-on can spill over in various ways for the U.S. and thus can be fraught political challenges and complex controversies. This is true particularly in countries like Laos and Cambodia, where such activities are increasingly concentrated and where our diplomatic footprint is relatively shallow. One way to build a pathway to addressing these more complicated challenges is to deepen our diplomacy and impact on the climate, energy, and food security issues I have discussed in my testimony. We can show our sustained commitment on these strategic and pragmatic opportunities in order to pave the way for building trust and building capacity in governance that brings impact to the harder to reach yet important issues. Finally, and I must underscore this point: Our activities in the Mekong need to be framed in a way that does not compel these countries to feel like they are needing to take sides between the U.S. and China. Southeast Asia does not respond well to being the grass upon which two elephants dance and has a practiced experience in balancing needs when great power competition plays out in the region.

I appreciate the opportunity to appear before this Committee, and thank you for the support that the U.S. Government has dedicated to the Mekong over the last two decades. I look forward to answering any questions you may have.