Since October 27, 2023, Burma’s military has been on the defensive across the country. Currently, ethnic armies in northern Shan State control much of the border with China, and a fierce battle rages in the Kayah State capital of Loikaw. In Rakhine State, the Arakan Army abandoned its ceasefire with the military and blitzed through dozens of junta posts.

In the resistance stronghold of Chin State, Northwest Burma, ethnic Chin forces have captured at least seven towns since October, including the key border crossing of Rikhawdar and nearly every remaining junta outpost in the countryside.

Chin military successes were crowned with a political breakthrough. 235 attendees from across Chin State, neighboring Chin communities, and the broader Chin diaspora came together for the first Chinland Conference at Victoria Base from December 4 to December 7, 2023. The attendees ratified a new Chinland Constitution and set up a Chinland Council with the mandate to form a Chin government, including a legislature, executive branch, and judiciary, within 60 days.

Unity has long eluded the Chin people, who comprise dozens of distinct cultures and dialects, and the new council is the result of more than two years of negotiations. The conference is only the second serious attempt to unite one of Burma’s minority ethnic groups under a statewide authority since the Spring Revolution began. Like the Karenni State Interim Executive Council, formed by the Karenni resistance in June 2023, the Chinland Council recognizes both pre-coup ethnic-armed organizations (EAOs) and democratic forces organized after the coup. Unique to the Chin context, the Chinland Council contains elected Members of Parliament who avoided capture in the 2021 coup.

The Chinland Council may also be charting the way to a new federal model of cooperation with other democratic forces. The Constitution explicitly states that the Chinland Council and Government will work in coordination with the democratic National Unity Government, the National Unity Consultative Council, and other “federal units.” This means that the Chin military will coordinate with national resistance actors, including EAOs, which could provide a chance to build on Operation 1027 with nationwide offensives.

The Chinland Council carries not only national but also international significance. Since the 2021 coup, tens of thousands of Chin refugees have fled to India’s Mizoram State, just across the border from Chin State and Sagaing Region, the site of recent Chin victories. Anti-Indian insurgents have also taken refuge in Burma with the junta’s tacit permission. As with Myanmar’s other border areas, the junta and its clients are involved in the local drug trade and other criminal activity as a lucrative source of revenue. A united and democratic Chinland would make a more trustworthy partner for India on border issues than the Burmese military ever was.

Though not all in Chin State agreed to participate in the Chinland Council, the process is broadly representative of over 80% of armed groups and all three of its major post-coup power centers: the Chin National Front, Chinland Defense Forces, and Members of Parliament.

Chin National Front

The Chin National Front (CNF) and its armed wing, the Chin National Army, are Chin State’s veteran ethnic armed organization. Formed in 1988, the CNF led a low-level insurgency throughout the 1990s before agreeing to a series of ceasefires, including the 2015 Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA). While boasting a small number of fighters, the CNF was the literal standard-bearer for Chin nationalism throughout this period; the new Chinland Council and Constitution continue to use its flag. After the 2021 coup, the CNF resurged in relevance, leaving the NCA and forming part of K3C, an alliance of the four ethnic armed organizations aligned with the National Unity Government. They have now taken a central military coordination and training role among Chin forces.

Chinland Defense Forces

The bulk of resistance fighters today belong to one of the Chinland Defense Forces (CDFs) formed since the 2021 military coup, which are roughly equivalent to People’s Defense Forces (PDFs) in other parts of Burma. Many in the CDFs received training at CNF camps before returning home to found their own units. CDFs are categorized as either “Township CDFs,” corresponding to the formal administrative divisions of Chin State, or “Region CDFs,” corresponding to Chin State’s diverse dialect groups. As such, these organizations sometimes overlap in their operating areas or follow their own local or ethnic prerogatives. Membership in the CDFs skews younger, including urban professionals and civil servants from the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM). The CDFs are most responsible for administration in liberated areas: with the help of CDM members, they have resurrected pre-coup service delivery and set up their own local courts.

Chinland CDFs

Townland CDFs

- CDF-Hakha

- CDF-Thantlang

- CDF-Matupi

- CDF-Mindat*

- CDF-Kanpetlet

- CDF-Paletwa

- Chin National Organization/Chin National Defense Force (Falam)*

- CDF-Tonzang (Tedim)

- Zomi Federal Union/PDF-Zoland (Tedim)*

Region CDFs

- CDF-Zophei (Thantlang)

- CDF-Lautu (Thantlang)

- CDF-Mara (Matupi)

- CDF-Zotung (Matupi)

- CDF-Daai (Paletwa)

- CDF-Hualngoram (Falam)

- CDF-Siyin (Tedim)

- CDF-Kalay, Kabaw, Gangaw (Sagaing and Magway Regions)

*recognized by the Council, but not a participant

Members of Parliament

In Chin State, 27 of the 39 Members of Parliament (MPs) elected at the state and union level escaped arrest in 2021 and joined the revolutionary movement. State parliamentarians organized the Committee Representing Chin State Hluttaw (meaning parliament) and are active in resistance-controlled areas and across the border in Mizoram State, India. Union parliamentarians participate in the national-level Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw and work with the National Unity Government. Chin MPs continue to marshal support among the diaspora and organize humanitarian efforts for refugees and displaced people, while maintaining clear legitimacy as winners of the last free elections in pre-coup Burma. All these MPs are from the National League for Democracy, as regional parties in Chin State had limited electoral success prior to the coup. Given their technical expertise, nearly all MPs took a leading role in drafting the language of the Chinland Constitution.

Chinland Council

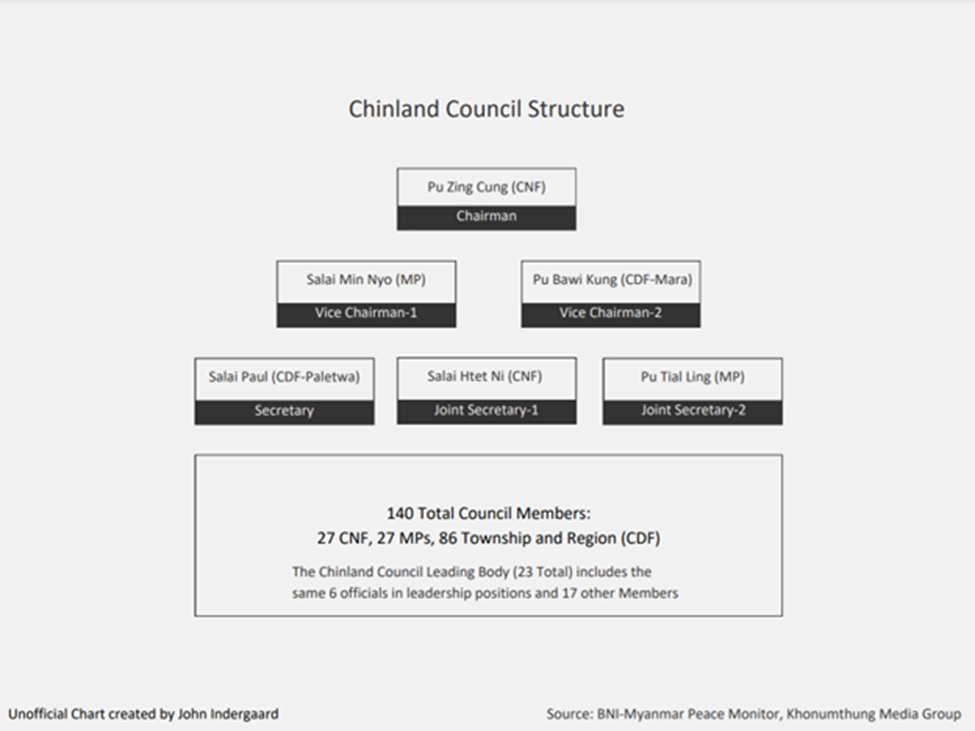

The Chinland Council is first and foremost a power-sharing institution, with representatives from three political poles: its leadership currently consists of two MPs, two CNF members, and two representatives from the CDFs, with CNF Chair Pu Zing Cung serving concurrently as Council Chair.

According to the Chinland Constitution, the full Chinland Council will consist of all 27 pre-coup Chin MPs, 27 representatives from the CNF, and 86 “township and region” representatives that correspond to the various CDFs. This arrangement recognizes the CNF’s place on the revolutionary vanguard while giving the bulk of representation to the CDFs, which administer most liberated territory.

Article 27 of the Chinland Constitution stipulates that the Council’s Leading Body should have three MPs, three representatives from the CNF, and 17 “township and region” representatives. Due to the difficulty of convening all 140 Council members in the jungle, this Leading Body has been formed as a flexible grouping that can meet more regularly.

In a press release from December 7, the Chinland Council stated that its three overall goals would be to establish Chinland’s national right to self-determination, to establish a federal union with political and national equality, and to establish democracy. This would include implementation of the Chinland Constitution and the formation of its three branches of government for the revolutionary period, which will remain accountable to the Council.

The majority of MPs and CDFs have signed onto this vision, and geographically cover much of the state as well. However, several Chin resistance organizations have refused to participate. In a joint press release on December 5, the Chin National Organization/Chin National Defense Force, CDF-Mindat, and Zomi Federal Union/PDF-Zoland announced that they would not attend the Chinland Conference. The townships of Falam, Mindat, and Tedim, where these groups are based, have historically had tense relationships with consolidating projects. Other groups from these townships, such as CDF-Hualngoram from Falam township and CDF-Siyin from Tedim township, already participate in the Council.

Of the 27 MPs from Chin State active in the resistance, 17 participated in the Chinland Conference and joined the Council. This includes MPs from seven of Chin State’s nine townships. Among the ten holdouts are the Falam delegation, the Tedim delegation, and one MP from Kanpetlet.

The Chinland Council continues discussions with these non-participant MPs and groups, insisting that it has “kept the door open for them to participate” and left room to accommodate them. Still, the three holdout groups formally established a “Chin Brotherhood” on December 30, protesting what they view as the CNF’s domineering role in the Council. The Chin Brotherhood has announced that they will respond collectively to attacks on any member, extending an open offer of membership to other interested parties.

Chinland Constitution

Contents of the Chinland Constitution

Preamble

Chapter 1: Basic Principles

Chapter 2: Chinland Structure

Chapter 3: Chinland Council

Chapter 4: Legislature

Chapter 5: Administration

Chapter 6: Judiciary

Chapter 7: National Defense Council

Chapter 8: Regional Administration

Chapter 9: Elections

Chapter 10: General Provisions

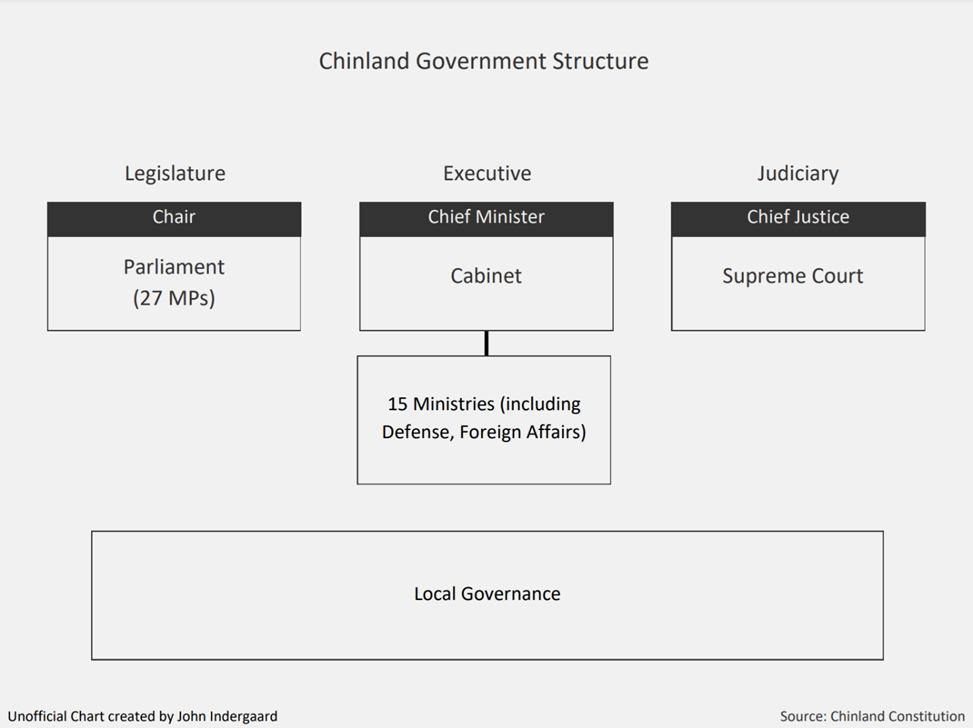

The Chinland Constitution is explicitly an interim document for the revolutionary period and lays out a government that broadly follows the structure of most parliamentary systems. The government will be split into three branches, led by the Parliament, Executive (Cabinet), and Supreme Court.

Chapter 8 of the Constitution also establishes a separate layer of local government but does not specify how it will look. In practice, this formalizes the system of administration seen in villages and towns already liberated by the resistance: pre-coup administrative structures that have been resurrected from the bottom-up with the participation of striking civil servants and local CDFs.

The impulse to limit and separate power runs throughout the document. For instance, the leadership team of the Chinland Council will not be permitted to serve concurrently in the National Unity Government, as Chair or Vice-Chair of the Parliament, in the Cabinet (including as Chief Minister), or in the Supreme Court. The Chinland Council itself will be limited to a total of two 2-year terms. In practice, this means that the CNF’s leadership of the Council will preclude it from holding the Chief Minister position for the next two years.

According to the Constitution, the interim parliament will be made up of the 27 MPs active in the revolutionary movement. While this seems simple in practice, this includes the 10 MPs who have not actually agreed to join the process yet. How their constituents in Falam and Tedim will be represented in the meantime remains unclear.

Formation of a Ministry of Defense and model for military coordination will likely be the most important component of the Chinland government’s work for the foreseeable future. While a defense minister will lead, it is not yet clear whether the disparate array of Chin armed forces will establish a single chain of command or use a model of joint operations. Equally unusual for a state government is the Foreign Affairs Ministry, which will exist for the revolutionary period and will likely focus on relations with India.

Other interesting provisions in the Constitution include Article 102, which sidesteps the issue of Chinland’s sometimes mutually unintelligible dialects by declaring its official languages to be unspecified “Chin languages,” as well as English and Burmese. Article 11 and 12 of the Basic Principles specify that the Chin people are the owners of the state’s natural resources and land; as a historically poor state, this means forests, particularly teak trees, as well as any undiscovered resources. Finally, Chinland will be an officially secular polity despite widespread adherence to Christianity.

In a nod to gender equity, Article 17 says “when forming the Chinland Council and Chinland Government, women’s participation shall be promoted.” This is a conscious effort to ensure that there are more women in positions of power in the new institutions, though one without quotas or more concrete commitments.

According to Article 96, “it is noted that the Interim Chin National Consultative Council and its roles and responsibilities have been transferred.” The ICNCC was founded on April 13, 2021 as a vehicle for Chin unity by the CNF, MPs, Chin political parties, and civil society organizations. However, its inability to produce a Chinland Council caused defections, culminating in the CNF’s exit in 2023. On December 7, the day after the Chinland Constitution was ratified, the ICNCC issued a statement that “no individual or organization has the right to dissolve the ICNCC, and the ICNCC will not transfer its roles and responsibilities.” The ICNCC thus continues to exist as an alternate political vehicle for the Chin MPs and groups who did not join the council’s process.

Unresolved Questions

Most in the Chin resistance demur when asked about their post-revolutionary goals, claiming that their current priority, shared with the rest of the country, is to topple the military junta. As a short interim document, the Chinland Constitution raises just as many questions as it answers.

For starters, why does the document choose “Chinland” over “Chin State”? The name has historical resonance harking back before the 1947 Panglong Agreement and creation of the Union of Burma. Much as the Chinland Council espouses a “federal union” as one of its main goals, the name implies a substantial revision of Chin State’s relationship to the center to include more autonomy. The transfer of natural resources and land ownership to the Chin people, rather than the center in Naypyidaw, may be just one of many changes to come.

If Chinland plans to develop a new relationship with the center, is it guaranteed to retain the same administrative boundaries? Much like other parts of Burma, about half of the Chin ethnic population lives outside the state. Several CDFs are based in or regularly operate in Sagaing and Magway Regions, namely CDF-Kalay, Kabaw, Gangkaw. The town of Kalay in Sagaing also has a large Chin population and special significance in Chin history. Conversely, the Arakan Army, based in neighboring Rakhine State, controls a swath of Paletwa township in Chin State, including the planned sites of India’s much-hyped Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Project. As a result, Chinland’s ability to fully govern the territory within the same administrative boundaries remains unclear.

Finally, the Chinland Government will need to address disagreements among the Chin with great care. What is the plan for incorporating the ICNCC and Chin Brotherhood members that continue to reject the Chinland government’s structure? Will a different relationship need to be worked out with some Chin sub-groups, much as the Chin seek to revise their relationship with Burma’s center? In neighboring Mizoram State, India, there are several autonomous district councils dedicated to the Mara and Lai, who are distinct from the dominant Mizo. Would this model work for the Chin?

Despite being a work in progress, the Chinland Council marks a new level of Chin organizational ability and a step towards broader unity, particularly between armed groups and civilian leadership. Whether this translates to success on the battlefield remains to be seen, as Chin forces prepare for a renewed offensive.

Zo Tum Hmung and John Indergaard are the executive director and project and advocacy coordinator, respectively, of the Chin Association of Maryland.