As risks from climate change to coastal cities continue to increase, governments, public and private investors, and the insurance industry need targeted risk information to prioritize action and build resilience where it matters most.

In response, the Stimson Center developed the Climate and Ocean Risk Vulnerability Index (CORVI). CORVI is a decision support tool which compares a diverse range of ecological, financial, and political risks across 10 categories and 96 indicators to produce a holistic coastal city risk profile. Each indicator and category are scored using a 1-10 risk scale relative to other cities in the region, providing a simple reference point for decision makers looking to prioritize climate action and resilience investment.

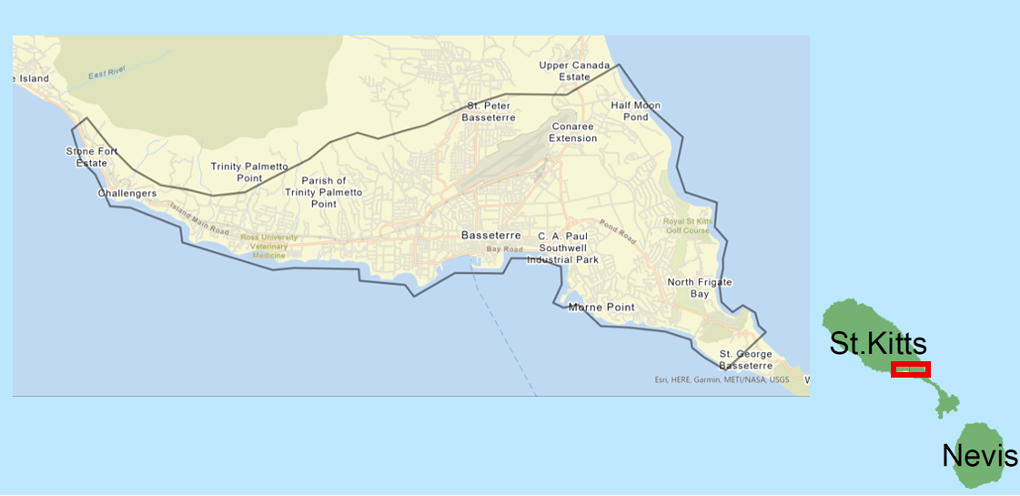

This report presents the CORVI Risk Profile for Basseterre, St. Kitts and Nevis. The profile combines empirical data, expert interviews, surveys, and desk research to analyze how climate and ocean risks are impacting the city. This information is used to develop detailed priority recommendations for Basseterre to reduce its climate vulnerabilities and work to build a sustainable future.

For more information on the CORVI methodology, please see the CORVI methodology page.

This risk profile was produced in collaboration with the Government of St. Kitts and Nevis, the Taiwan International Cooperation and Development Fund (TaiwanICDF), and the Taiwan Ocean Affairs Council.

Basseterre, the capital of and largest city in St. Kitts and Nevis, has a population of 14,000 people1Note: Saint Kitts and Nevis-The World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/saint-kitts-and-nevis/#people-and-society, retrieved 2021-09-12. , accounting for approximately 27% of the country’s population. St. Kitts and Nevis is located in the Caribbean at the southern edge of the Atlantic hurricane belt, where tropical cyclones occur from June to November.2Note: OECS, (2021),”Country analysis: resilience to climate change at a glance Saint Kitts and Nevis.” The proportion of the workforce employed in the tourism industry is expected to increase considerably over time, posing considerable challenges to urban planning and the natural environment that are being exacerbated by the impacts of climate change.

Climate change continue increase threats to coastal cities. In this study, a climate and ocean risk vulnerability assessment was conducted for Basseterre by using the “Climate and Ocean Risk Vulnerability Index (CORVI)” methodology established by the Stimson Center. CORVI is a decision support tool for public and private sectors to target climate action and build resilience. Empirical data and sixty experts’ surveys incorporated into the Basseterre CORVI risk profile are displayed across three risk areas, 10 categories and 96 indicators. These scores are supplemented with information on resilience planning already underway, and twenty-one interviews from experts in Basseterre.

Summary Findings

The CORVI analysis reveals significant vulnerability in the ecological risks, followed by financial and political risks. Notably, for all ten CORVI risk categories, Basseterre scored at the medium-high and medium risk levels. The highest category score is Fisheries (6.54), which reflects a high level of risk associated with unreported and unregulated fisheries coupled with an elevated reliance on fish as a food source. This is closely followed by the risks associated with degraded coastal ecosystems, particularly mangroves under Ecosystems (6.18) and key Major Industries (6.18), coastal and marine tourism. Other high risks indicators identified in the assessment include extreme heat events and hurricanes, both within the Climate (5.20) category.

Geology/Water (5.27) and Economics (5.23) are the other medium-high risk category scores. The score for the Geology/Water category reflects risks related to coastal erosion, coastal runoff and flooding, and saltwater intrusion into freshwater aquifers. The score for the Economics category reflects the key role that Basseterre plays in the economy of St. Kitts and Nevis and the risks associated with the city’s informal economy, which is characterized by workers and firms with fewer financial resources, inhibiting their ability to invest in resilience measures and to recover after a disaster.

The blue economy in Basseterre is critical to the economic prosperity of the city and the Caribbean Sea region. Although Basseterre has strengthened its infrastructure and seaport facilities, complex ecosystem and major industries still have high, climate change induced risks. Climate and ocean risks threaten the tourism, shipping, and fisheries industries. Moreover, the frequency and intensity of hurricanes of the Caribbean Sea have increased over the past decade. After the passage of an extreme weather event through Basseterre city area, many sectors such as tourism, shipping, and fisheries are affected. This results insignificant ecological and financial damage, which, if left unaddressed, could impede the ability of the city to build climate resilience.

In this regional climate change report, the city-level empirical data for each indicator is insufficient, so survey and expert interviews are adopted to complement the information. However, the results of the survey did not necessarily correspond to the empirical data and the interviews. Hence, the establishment of a systematic collection of regional climate change data in the future will enable better climate adaptation plans.

Basseterre Risk Profile

Although the government of St. Kitts and Nevis has proposed and passed several plans and projects for strengthening climate resilience, a lack of funding and inadequate technical and human resources have hindered effective implementation. In addition, alignment between the public and private sectors needs to be improved. Addressing these challenges will position Basseterre’s decision-makers well to provide leadership on climate change, mitigate the threat posed by climate and ocean risks, and build a resilient and sustainable future.

Three CORVI risk profile identifies three priority areas for action to build resilience and address systemic risks:

- Increase coordination and planning between the government and private sector to improve preparation and response for climate risks such as sea level rise, storm surge, coastal erosion, and heat waves. The government could establish a permanent climate coordinating committee across the multiple ministries and with the private sector who meets regularly to work together to prioritize necessary actions annually to proactively address the most pressing climate risks, including those identified in this assessment; improve waste treatment infrastructure and stormwater management, prioritize reducing impacts on vulnerable populations, and establish a city- or island-wide business resumption plan to ensure a swift restart of services and business activity after a hurricane or other disaster.

- Expand renewable energy and diversify the location of power generation to reduce reliance on imported fossil fuels, improve grid resilience during extreme weather events, and facilitate post-disaster recovery efforts. The government could work with the St. Kitts and Nevis Chamber of Industry and Commerce, the St. Kitts Electricity Company, and other stakeholders to increase awareness, streamline regulations, implement financial incentives, and establish microgrids. This expansion could include solar, wind, and geothermal energy.

- Support a sustainable blue economy founded on healthy marine and coastal ecosystems. The government of St. Kitts and Nevis could work with private partners and civic society, such as the Sustainable Destination Council, to enhance and expand efforts to increase coverage and health of native mangroves, seagrasses, and corals, actively implement fisheries and ecosystem management regulations, improve wastewater management, and mitigate erosion from cruise ship terminals. All of this would help improve the long-term viability of Basseterre’s key economic sectors, protecting jobs and livelihoods.

By implementing these suggestions, Basseterre can attract financial resources and direct them to the highest needs to effectively build climate resilience and ensure a safe and sustainable future.

Ecological Risk

Basseterre faces an elevated level of ecological risk, which includes five of the six highest indicator scores in the CORVI assessment. This risk is distributed across the four categories: Fisheries, Ecosystems, Geology/ Water, and Climate Change, all of which received medium-high weighted average risk scores. Although the category scores are closely grouped, the indicator scores within each category are significantly more divergent. Three of the four categories including high risk indicator scores and all four containing multiple medium-high and medium risk indicator scores.

- The FISHERIES category (expert weighted avg 6.54) includes the second and third highest risk indicator scores in the Basseterre assessment, unreported catch estimate (8.56) and percentage of fisheries certified by Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) (8.02). Fish consumption (6.34), nearshore fish stock status (6.23), capacity of fisheries enforcement institutions (6.05), and offshore fish stock status (5.78) received medium-high risk scores.

- In the ECOSYSTEMS category (expert weighted avg 6.18), high and medium-high risk scores highlight the declining coverage and health of key coastal ecosystems, including mangroves (coverage 7.69, health 6.82), coastal sand dunes (coverage 6.44, health 6.70), coral reefs (coverage 6.64, health 5.22), and seagrasses (coverage 6.15, health 5.97). The medium-high risk score for the rate of occurrence of harmful algal blooms (6.80) highlights additional risks.

- In the GEOLOGY/WATER category the expert weighted avg was 5.27. There were medium-high risk scores for coastal erosion (6.04), water quality (6.03), saltwater intrusion (5.86), risk of flooding (5.84), and sea-level rise (5.24), highlight the threats posed to the urban center by both ocean risks and runoff from the mountainous interior.

- Although the CLIMATE category (expert weighted avg 5.20) scored the lowest under ecological risks, it includes two of highest risk indicators: extreme heat events (7.87) and number of hurricanes (7.67). Medium-high risk scores for change in sea surface temperature (5.81) and number of droughts (5.44) further highlight the threats posed by increasing temperatures and extreme weather patterns.

The highest scored risks in the ecological risk area were related to the sustainability of St. Kitts and Nevis’ fisheries. The level of unreported catch (8.56) and MSC certified fisheries (8.02) both scored as high risk and the status of nearshore (6.23) and offshore (5.78) fish stocks both scored as medium-high risk. Fish and seafood production has increased rapidly in recent years; the number of tons caught in 2018 was almost 5 times that caught in 2013.3Note: Food and Agriculture Organization. “Fish and Seafood Production.” Our World In Data. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/fish-seafood-production?tab=chart®ion=NorthAmerica&country=~KNA That same year, the total value of fish catches in St. Kitts and Nevis reached 10 million East Caribbean Dollars (approximately 3 million USD).4Note: Government of Saint Kitt and Nevis, (2021), "Marine Resources." The fisheries sector does not play a major role in the economy of St. Kitts and Nevis, contributing only 0.57% to GDP in 2020.5Note: Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism (2021) CRFM Statistics and Information Report - 2020 The value of all seafood exports was under $200,000 in 2017 while seafood imports totaled $4.2 million that same year.6Note: UN Comtrade. “Saint Kitts and Nevis trade in fish, crustaceans, molluscs, and aquatic invertebrates.” https://dit-trade-vis.azurewebsites.net/?reporter=659&type=C&commodity=03&year=2017&flow=2 However, the fisheries sector is important in two ways for Basseterre. First, seafood is an essential source of nutrition (specifically, protein) for the residents of St. Kitts and Nevis. Annual seafood consumption per capita of was 36.1 kg in 20177Note: Ritchie H and RoserM, (2019), "Seafood Production," Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: https://ourworldindata.org/seafood-production [Online Resource].), 1.75 times higher than the global average of 20.3 kg. Second, fishing is a key pillar of the country’s economic resilience, demonstrated in recent years by many people turning to fishing while the COVID-19 pandemic devastated the country’s tourism industry.8Note: Morgan, Rayne. “St. Kitts & Nevis workers turn to fishing amid tourism shutdown.” Caribbean Employment Services Inc., September 16, 2021. https://caribbeanemployment.com/caribbean-jobs-and-employment/st-kitts-nevis-workers-turn-to-fishing-amid-tourism-shutdown-says-doctor-marc-williams-director-department-of-marine-resources-maritza-queeley-port-state-control-officer/?noamp=mobile

The sustainable management of these fisheries is a challenge for St. Kitts and Nevis. According to the Ocean Health Index, the sustainability of wild-caught seafood in St. Kitts and Nevis is lower than all but four countries/territories in the Caribbean.9Note: Ocean Health Index. “2021 Index: Food Provision: Wild Caught Fisheries”. https://oceanhealthindex.org/global-scores/ Interviewees have noted that fishermen now must fish further from the shore to maintain previous catch levels.10Note: Interview with food service industry, St. Kitts. Availability of fish at the local market on Bay Road, attributed by interviewees to overfishing.11Note: Interview with local retail industry, Basseterre, St. Kitts and Nevis. March 1, 2022. Unreported fishing is estimated to account for 60%–80% of the fishing in this country and has increased gradually in the past two decades (1995–2018), according to unofficial estimates12Note: Sea Around Us, "Catches by Reporting status in the waters of Saint Kitts & Nevis," https://www.seaaroundus.org/data/#/eez/659?chart=catch-chart&dimension=reporting-status&measure=tonnage&limit=10, retrieved 2021-09-22.. The European Union added St. Kitts and Nevis to its list of nations warned about non-cooperation in combatting illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing in December 2014, known as a ''yellow card''.13Note: European Parliament (2022), "Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing." St. Kitts and Nevis acceded to the Agreement on Port State Measures (PMSA), the first binding international agreement to specifically target IUU, in December 2015. Nonetheless, the country remains on the EU warning list as of May 2022, one of nine countries worldwide, one of the longest stretches of time for any country.

In the past decade, the government of St. Kitts and Nevis has established several regulations related to fishery management. In 2015, it announced a national plan of action to prevent, deter, and eliminate IUU (NPOA-IUU).14Note: Government of Saint Kitt and Nevis, (2015) "National plan of action to prevent, deter and eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing." The NPOA-IUU was developed in accordance with the FAO International Plan of Action to Prevent, Deter, and Eliminate IUU Fishing, and is predicated heavily “on ownership and active participation by fishers” to implement the plan.15Note: Department of Marine Resources. “National plan of action to prevent, deter and eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing.” Government of St. Kitts and Nevis. July 31, 2015. In 2016, the government declared the 2-mile radius (approximately 3.2 km) St. Kitts and Nevis Marine Management Area (SKNMMA), becoming the first Caribbean country to designate a national marine spatial plan.16Note: Schill, Steven R., et. al. “Regional High-Resolution Benthic Habitat Data from Planet Dove Imagery for Conservation Decision-Making and Marine Planning.” Remote Sensing. October 21, 2021. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-4292/13/21/4215 The SKNMMA also makes St. Kitts and Nevis one of five countries to achieve the Caribbean Challenge Initiative goal of protecting 20% of the nearshore environment.17Note: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/collections/c1b717765c764ccba91e3ed5047bcd6a?item=1 Within the SKNMMA, an area of 117 km2 has been established as a conservation zone to ensure sustainability of the fishery industry. The coastline of Basseterre is also a designated multiple-use area (for transportation, tourism, fishing, and conservation).18Note: Agostini, V. N., Margles, S. W., Knowles, J. K., Schill, S. R., Bovino, R. J., & Blyther, R. J. (2015). Marine zoning in St. Kitts and Nevis: a design for sustainable management in the Caribbean. Ocean & Coastal Management, 104, 1-10. However, interviewees cited a low level of buy-in among fishermen for preservation and protection measures.19Note: Interview with representatives from offshore recreation industry. The capacity of fisheries enforcement institutions (6.05) was scored as a medium-high risk, reflecting concerns among surveyed experts about the government's capacity to successfully implement and enforce these protection measures, despite recent improvements in the capacity of the Department of Marine Resources, which more than doubled its staff between 2014 and 2018.20Note: Government of St. Kitts and Nevis. “Country Biodiversity Profile: St. Kitts and Nevis.” Sixth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity. 2018. https://chm.cbd.int/api/v2013/documents/C0A7116F-F642-2089-08C4-81605C16F1BC/attachments/208600/St.%20Kitts%20and%20Nevis%20Country%20Biodiversity%20Profile%20.pdf

Fishing, along with coastal and marine tourism and coastal infrastructure protection, depends on healthy marine and coastal ecosystems, which in St. Kitts and Nevis includes coral reefs, mangroves, seagrass beds, wetlands, and sand dunes.21Note: Agostini, VN, Margles, SW, Schill, SR, Knowles, JE and Blyther, RJ, (2010). "Marine zoning in Saint Kitts and Nevis: A path towards sustainable management of marine resources," The Nature Conservancy. These ecosystems provide a variety of ecosystem services, including carbon sequestration, marine habitat, sediment stabilization, and nutrient cycling. They face substantial threats, however, as reflected by the high and medium-high risk scores for 11 of the 14 indicators in the Ecosystems category. Much of St. Kitts and Nevis’ wetlands and mangroves that existed in 2005 have since disappeared, principally due to hotel and resort development. Mangrove coverage (7.69) in particular has fallen to less than 0.7 km2,22Note: “Mangrove ecosystems of Saint Kitts and Nevis”. UNESCO. 2022. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000382225 with small stands remaining on St. Kitts’ southeast peninsula, Sandy Point, and Nevis’ bays.23Note: Ibid. This represents a decline of almost 20% since 1980, when the country had 0.85 km2 of mangroves.24Note: “Global Forest Resources Assessment 2005: Thematic Study on Mangroves. St. Kitts and Nevis Islands: Country Profile”. Food and Agriculture Organization. August 2005. https://www.fao.org/forestry/9364-060fdce72c7437ec5a4eb92158834e984.pdf

Coral reef coverage (6.64) around the islands has also fallen considerably.25Note: Ibid. Large-scale coral bleaching, attributed to high surface water temperature,26Note: Wilkinson, CR and Souter, D, (2008). "Status of Caribbean coral reefs after bleaching and hurricanes in 2005". occurred in the Caribbean Sea in 2005, when ocean temperatures rose to 90°F.27Note: Interview with representatives from offshore recreation industry. More recently, a disease known as stony coral tissue loss disease (SCTLD) has been killing hard coral at an extremely rapid rate, with mortality rates approaching 100% for some species.28Note: Ernst, Jeff. “Caribbean Reefs are Dying from a Mysterious Disease.” St. Kitts & Nevis Observer. August 17, 2021. https://www.thestkittsnevisobserver.com/caribbean-reefs-are-dying-from-a-mysterious-disease/ Human impacts, including dredging project, wastewater discharge, plastic pollution, and runoff from hillside development projects have reduced the health of coral reefs, compounding the effects of heat events and disease.29Note: Interview with representatives from offshore recreation industry. Coral reefs can have the highest biodiversity among all ecosystems and provide habitat to a variety of sea animals, which maintain fishery resources (mainly snapper) and the tourism industry. However, interviewees noted the decline of biodiversity and numbers of reef fish in places like Paradise Reef. Moreover, coral reefs are natural barriers to the coastline and reduce direct impact of waves caused by hurricanes or storm surges. The St. Kitts and Nevis Department of Environment and Department of Marine Resources launched the Coral Reef Early Warning System in 2018 to improve data on the country’s marine environment.30Note: Niland, Dana. “St Kitts Launches New Coral Reef Monitoring Program.” Caribbean Journal. April 26, 2018. https://www.caribjournal.com/2018/04/26/st-kitts-launches-new-coral-reef-monitoring-program/

Seagrass coverage (6.15) has expanded considerably, including dense beds around Basseterre. However, this expansion has been fueled by an invasive species of seagrass, halophila stipulacea. H. stipulacea appears to have been introduced during the Christopher Harbor Development Project and by 2018 had already eliminated over 10% of native seagrass beds.31Note: Government of St. Kitts and Nevis. “Country Biodiversity Profile: St. Kitts and Nevis.” Evidence on the impacts of H. stipulacea on other native species is so far mixed. For example, studies have found native fish to be larger on H. stipulacea beds but juvenile fish to be more abundant on native seagrass beds. Additional study and monitoring are warranted.32Note: Winters, Gidon, et. al., “The Tropical Seagrass Halophila stipulacea: Reviewing What We Know From Its Native and Invasive Habitats, Alongside Identifying Knowledge Gaps.” Frontiers in Marine Science. May 26, 2020. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2020.00300/full Interviews noted that the revival of seagrass beds in some overfished areas around Basseterre has helped the recovery of large fish, lobsters and conchs.33Note: Interview with representatives from food service industry, St. Kitts.

St. Kitts and Nevis is also facing risks from rising terrestrial air temperatures. Increasing air temperatures are likely to drive higher rates of heat stress and related illnesses, especially in the elderly and infirm.34Note: Government of St. Kitts and Nevis. “The National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy for Saint Christopher and Nevis.” October 2018. Extreme hot temperatures can also damage transportation and power infrastructure.35Note: Berkowitz, Bonnie, Arthur Galocha, and Júlia Ledur. “We built a fake metropolis to show how extreme heat could wreck cities.” The Washington Post. August 11, 2022. While Basseterre is unlikely to face those extremes in the near future, St. Kitts and Nevis has seen an increase of 30 hot days per decade between 1971 and 2018, the fastest rate of increase of Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) member states,36Note: “Climate Trends and Projections for the OECS Region.” Organization of Eastern Caribbean States. April 1, 2020. reflected in the high risk score for Number of Extreme Heat Events (7.87). Rising population density in the center of Basseterre exacerbates the impact of heat, but air conditioning is not common.37Note: Interview with representatives from National Disaster Coordinator, NEMA (National Emergency Management Agency) In response, the government plans to establish an early warning system for heatwaves and integrate heat stress considerations into the construction of new buildings and retrofit of old ones.38Note: Government of St. Kitts and Nevis. “The National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy for Saint Christopher and Nevis.”

There have been no hurricane landings in St. Kitts and Nevis since Hurricane Georges in 1998. The impacts of recent hurricanes on other eastern Caribbean states have highlighted the risks the region faces, most starkly illustrated by Hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017, which caused damage to Dominica worth 224% of the island’s GDP and destroyed or damaged 95% of housing on Barbuda.39Note: World Bank Group. “A 360 degree look at Dominica Post Hurricane Maria”. November 28, 2017. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2017/11/28/a-360-degree-look-at-dominica-post-hurricane-maria These risks are highly salient to experts in St. Kitts and Nevis, reflected in the risk score for Hurricanes (7.67), the sixth highest score in this assessment.

Although hurricanes in the Caribbean region over the past decade have not directly hit Basseterre, nearby extreme storms have impacted the city with gusty winds, heavy rainfall, and increase storm surges. The most vulnerable neighborhoods to hurricanes are principally those along the western coastline, including Challenger’s Road and Bay Road, and Port Zante.40Note: Interview with representatives from National Disaster Coordinator, NEMA (National Emergency Management Agency) In 2017, Hurricane Irma caused an estimated $20 million in damages to St. Kitts and Nevis,41Note: EM-DAT https://public.emdat.be/ Accessed September 6, 2022 including damages to housing and public infrastructure.42Note: “Hurricane Irma leaves St. Kitts and Nevis with initial $53.2 million in damages”. St. Kitts & Nevis Observer. September 15, 2017. The number of strong hurricanes, defined as category 4 and category 5 storms, passing near St. Kitts and Nevis has been increasing, which is consistent with relevant research of the Caribbean Sea.43Note: Wilkinson, CR and Souter, D, (2008). "Status of Caribbean coral reefs after bleaching and hurricanes in 2005". The frequency of these strong hurricanes is projected to increase by 25%–30%, according to a report by the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States.44Note: Saint Kitts and Nevis-The World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/saint-kitts-and-nevis/#people-and-society, retrieved 2021-09-12.

This rainfall from hurricanes and other storms can result in flooding, both from storm surge and runoff flooding from St. Kitts’ mountainous interior. Flooding can directly damage property, infrastructure, and agriculture and indirectly cause freshwater shortages, food supply disruptions, and water-borne diseases. Stormwater management, and the lack of adequate wastewater treatment were noted as key issues by interviewees, including the impacts of untreated storm and wastewater on critical coastal ecosystems. Flood risk in Basseterre is not homogenous, and some areas are more flood prone, including Conaree Hills (very high risk), Half Moon Pond (high risk), North Frigate Bay (moderate risk), and Lower College Street Ghaut (moderate risk). A detailed map of flood risk is presented in Figure 1.

Projected sea level rise (5.24) is also a concern for Basseterre. By 2018, sea levels had already risen by around 0.08 meters,46Note: “Climate Change Knowledge Portal: St. Kitts and Nevis: Sea Level Rise.” World Bank Group. https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/st-kitts-and-nevis/impacts-sea-level-rise and the country has lost more than 25% of its land area since 1961.47Note: McCarthy, Niall. “St. Kitts and Nevis Has Shrunk by a Quarter Since 1961”. Statista. August 16, 2018. https://www.statista.com/chart/1740/land-area-lost-since-1961/ By 2032, the World Bank projects that St. Kitts and Nevis will experience sea level rise of between 0.12 and 0.19 meters. By 2050, the rise is projected to increase to 0.20 to 0.31 meters. By the end of the century projections diverge substantially based on expected greenhouse gas emissions, with the IPCC’s intermediate scenario (RCP 4.5) projecting between 0.49 to 0.63 meters.48Note: “Climate Change Knowledge Portal: St. Kitts and Nevis: Sea Level Rise.” World Bank Group. https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/st-kitts-and-nevis/impacts-sea-level-rise This sea level rise is likely to increase the risk of coastal flooding, especially for areas that are already at higher risk, and may increase coastal erosion, already scored a medium-high risk (6.04), and saltwater intrusion in coastal aquifers, also already a medium-high risk (5.86). Interviews noted that coastal erosion and sea level rise also threaten sea turtle nesting sites. Civil society organizations, such as the St. Kitts Sea Turtle Monitoring Network have relocated nests to safer areas with the support of the government.49Note: Interview with representatives St. Kitts Sea Turtle Monitoring Network.

Freshwater availability for St. Kitts and Nevis is already limited; the island has the highest level of water stress among OECS member states with 51% of available renewable freshwater resources being withdrawn, more than 3.5 times higher than the next most stressed island state, St. Lucia.50Note: “Country Analysis: Resilience to Climate Change at a Glance: St. Kitts and Nevis.” OECS. July 2021. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354323068_OECS_CCASAP_Country_analysis_resilience_to_climate_change_at_a_glance_-_Saint_Kitts_and_Nevis Interviews noted that population growth has driven increased water demand, exacerbating this situation.51Note: Interview with representatives from Maitland & Maitland Associate. This is exacerbated by droughts (5.44) such as the one in 2017 which resulted in severe water rationing.52Note: “Vulnerability Assessment and Water Utility Adaptation Plans St Kitts and Nevis – Water Sector Adaptation Plan.” HR Wallingford. August 2021. There are 31 underground wells provide 70% of the potable water on St. Kitts, with surface water from 31 delineated watersheds accounting for the remaining 30%.53Note: Ibid. The Basseterre Valley Aquifer system is the island’s only major groundwater basin,54Note: Ibid. and therefore critical to ensuring Basseterre has access to high quality freshwater (6.03). In recent years, proposals to build a school on the Basseterre Valley Aquifer have generated substantial controversy due to the risks of contamination of the aquifer’s freshwater.55Note: “Local Experts Urge Government to Halt Plans for Construction of a New Basseterre High School on the Aquifer”. SKN Web News. November 26, 2018. http://sknwebnews.com/local-experts-urge-government-to-halt-plans-for-construction-of-a-new-basseterre-high-school-on-the-aquifer/ Pressure on St. Kitts’ water resources has led to a requirement that major tourism projects construct and use their own private desalination systems, which is employed by both the Marriott and Park Hyatt hotel. This helps reduce the risks of water loss from continuous piped water supply (4.59) and diminishes the strain on public water systems. However, it increases construction and operation costs to tourism infrastructure.

Sargassum has become a rising crisis in the Caribbean in the last decade, reflected in medium and medium-high risk scores for harmful algal blooms (6.80) and sargassum abundance (5.00). Interviews noted that the government began a program of clearing sargassum in 2015.56Note: Interview with representatives from food service industry, St. Kitts, March 4, 2022 The hazard continues to rise, however, with sargassum levels in the Atlantic hitting a new record in June 2022, exceeding the previous record by 20%.57Note: “A record amount of seaweed is choking shores in the Caribbean.” The Associated Press. August 3, 2022. https://www.npr.org/2022/08/03/1115383385/seaweed-record-caribbean The UN Caribbean Environment Program has cited rising ocean temperatures and fertilizer runoff as possible drivers of sargassum.58Note: Ibid. Large masses of sargassum have driven declines in tourism and fish catch (most notably in 2017), falling seagrass, coral reef, and sponge populations, and can emit hydrogen sulfide gas, which can affect people with respiratory problems.59Note: Ibid. Sargassum blooming is more common on the Atlantic coast of St. Kitts and Nevis,60Note: Government of Saint Kitt and Nevis, (2019), "6th National Report for the Convention on Biological Diversity". which includes parts of Basseterre, such as the key tourist areas of Frigate Bay and Half Moon Bay.

Basseterre: Ecological Risk

Financial Risk

The Blue economy is important to Basseterre as seen through the high financial risks calculated in the Major Industries category. This includes the highest risk indicator of the whole assessment, the percent of the national economy based in tourism (8.70). The Economics and Infrastructure categories also encompass key risks for the city, with at least half of the indicators in each scored as medium-high risks.

- The MAJOR INDUSTRIES category (expert weighted avg 6.18) includes the highest risk score throughout the assessment for any single indicator, the share of tourism in the national economy (8.70). Port Zante also plays a critical economic role, reflected in the medium-high risk score for the port and shipping industries (6.60).

- The ECONOMICS category (expert weighted avg 5.23) highlights the importance of Basseterre to the overall economy of St. Kitts and Nevis (7.18). The category also includes indicators showing the national economy’s strength before the COVID-19 pandemic, with reduced levels of public debt (5.38) and comparatively low unemployment (4.60).

- The INFRASTRUCTURE category (expert weighted avg 4.63) scored lower than Major Industries and Economics, with medium risk scores for the resilience of the power grid (3.78), water distribution infrastructure (3.92) airport (4.16), and seaport (4.82). However, there are medium-high risk scores for renewable energy (6.69), shoreline development (6.03), low-income housing in flood zones (5.59) and damage from extreme weather events to commercial infrastructure (5.19) and housing (5.15). These infrastructure risks underline the compounding risks to city residents.

The key industry in St. Kitts and Nevis is tourism, which make up around a third of GDP in the years leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic.61Note: “Tourism in Saint Kitts and Nevis.” World Data. https://www.worlddata.info/america/stkitts-nevis/tourism.php Tourist arrivals peaked at nearly 1.3 million in 2018, with almost 90% accounting for cruise ship passengers.62Note: “Real Sector Statistics - Selected Tourism Statistics.” Eastern Caribbean Central Bank. https://www.eccb-centralbank.org/statistics/tourisms/comparative-report A slight decline in 2018 was followed by a 75% drop in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic,63Note: Ibid. contributing to a 14% fall in GDP.64Note: “Real GDP Growth: Annual Percent Change.” IMF World Economic Outlook (April 2022). https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDP_RPCH@WEO/KNA Basseterre is the main tourist destination in St. Kitts and Nevis. The government promotes tourism development, using various policies to boost the construction of infrastructure such as hotels, vacation apartments, duty-free shops, and shopping centers. It has also expanded Robert L. Bradshaw International Airport in Basseterre, increasing the number of flight routes and air traffic capacity. Port Zante, which is a deep-water harbor in Basseterre, was established for the hosting and berthing of cruise ships and the handling of cargo. This port is a relatively new and upscale cruise port in the Caribbean and can accommodate the largest cruise ships in the world. The importance of the sector is reflected in percent of the national economy based in tourism (8.70) the highest indicator risk score in this assessment.

The strength of the economy of St. Kitts before the pandemic gave the country the flexibility and financial space to help cushion the effects of the sharp decline in tourist arrivals in 2020. Before the pandemic, unemployment in St. Kitts and Nevis was the lowest in the region,65Note: “St. Kitts and Nevis 2021 Article IV Consultation – Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for St. Kitts and Nevis”. International Monetary Fund. October 2021. reflected in a medium risk score (4.60). In addition, a decade of fiscal surpluses and a sovereign debt restructuring helped reduce public debt (5.38) from a peak of 145% of GDP at the end of 2010 to 52% of GDP at the end of 2019.66Note: Ibid. Debt increased to 61% of GDP in 2020 due to a contraction in GDP and economic support programs for those who became unemployed during the pandemic, including monthly stipends, deferrals on residential electricity bills, waivers for commercial rent for small businesses leasing space through the Ministry of Tourism and Transport and reductions in some taxes.67Note: “CARICOM Business Newsletter”. Vol. 4, No. 27. July 10, 2021. https://caricom.org/wp-content/uploads/Caricom-Business-July-10-2021-vol-4-no-27.pdf Tourist arrivals have begun recovering in 2022, with stay over visitor arrivals recovering faster than cruise passenger arrivals.68Note: “Tourism and Travel”. St. Kitts and Nevis Department of Department of Statistics, Ministry of Sustainable Development”. Accessed October 27, 2022. https://www.stats.gov.kn/topics/economic-statistics/tourism-and-travel/

St. Kitts’ shift to a tourism-driven economy occurred in the early 2000s after a long decline of the country’s previously dominant industry, sugar production. The key industry in St. Kitts and Nevis since before independence, sugar entered a sharp decline in the 1970s and the government closed the sugar industry in 2005 after years of annual losses equivalent to 3%–4% of GDP.69Note: Department of Investment Services, Ministry of Economic Affairs, (2012),"Investment Guide to Saint Christopher and Nevis, “https://www.taiwanembassy.org/kn/post/1184.html, retrieved 2021-09-21. In conjunction with a shift to promoting tourism, the government of St. Kitts and Nevis has embarked on an effort to diversify the agriculture sector.70Note: SKIPA, https://investstkitts.kn/, retrieved 2021-09-21. For example, the Agricultural Development Strategy includes financial incentives, efforts to increase land availability, investments in agroprocessing technology, and connecting farmers to tourist establishments. However, the country remains a net food importer of crops, with less than 10% of the fresh produce consumed grown locally,71Note: “St. Kitts Marriott Resort & The Royal Beach Casino Partners with The Ocean Foundation, Grogenics and the Local Community to Address Sargassum.” The Ocean Foundation. August 18, 2021. https://oceanfdn.org/st-kitts-sargassum/ while agriculture remains a marginal share of the economy (4.40). Likewise, despite increases in seafood production,72Note: Food and Agriculture Organization. “Fish and Seafood Production.” Our World In Data. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/fish-seafood-production?tab=chart®ion=NorthAmerica&country=~KNA the fisheries sector is not a major industry, contributing only 0.5% to GDP in 2014 and making up less than $200,000 in exports in 2017.73Note: UN Comtrade. “Saint Kitts and Nevis trade in fish, crustaceans, molluscs, and aquatic invertebrates.” Seafood is an important source of nutrition and has the potential to serve as an economic fallback, with some sources suggesting that those employed in the tourist industry turned to fishing during COVID-19.74Note: Morgan, Rayne. “St. Kitts & Nevis workers turn to fishing amid tourism shutdown.” Combined, agriculture and fisheries account for less than two percent of national GDP.75Note: “Agriculture, forestry, and fishing, value added (% of GDP) - St. Kitts and Nevis.” World Bank Open Data. Accessed September 7, 2022. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NV.AGR.TOTL.ZS?locations=KN&view=chart

The importance of Basseterre’s port and shipping industries (6.60) is shown in its medium-high risk score. Port Zante in downtown Basseterre includes the cruise terminal and can accommodate the largest cruise ships in the world. It is also home to frequent ferry operation between Basseterre and Charlestown, the capital of Nevis, as well as intermittent service between Basseterre and Oranjestad, Sint Eustatius, and between Basseterre and its neighbor state St. Marten.76Note: Department of Investment Services, Ministry of Economic Affairs, (2012),"Investment Guide to Saint Christopher and Nevis, "https://www.taiwanembassy.org/kn/post/1184.html, retrieved 2021-09-21. Local experts reiterated the importance of the port along with ongoing efforts to reduce storm damage to port infrastructure and increase port resilience. Hurricane Georges and Hurricane Lenny destroyed the cruise ship pier in 1998 and 1999, respectively,77Note: Leonard A Nurse, “The Vulnerability of Caribbean Ports to the Impacts of Climate Change: What Are the Risks?,” United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, September 30, 2011., 22. reflected in the medium risk score (4.82) for port resilience.

Hurricanes Georges and Lenny caused considerable damage to St. Kitts and Nevis beyond the port, totaling $445 million and $42 million respectively.78Note: “St. Kitts and Nevis: Updated Nationally Determined Contribution.” Government of St. Kitts and Nevis. October 2021. Since then, St. Kitts and Nevis has experienced major market losses (6.00) from Hurricane Omar (2008, $11 million in economic loss and damage), Hurricane Earl (2010, $3 million), subtropical storm Otto (2010, $20.1 million), Hurricane Irma (2017, $19.7 million), and Hurricane Maria (2017, $7.9 million). The medium-high risk score also encompasses concern that a direct impact from a hurricane, which the country has not experienced since 1998, would cause significantly higher losses. Several interviewees noted that adaptation tends to be reactive versus proactive, and mentioned the lack of a comprehensive disaster management strategy, particularly including a business resumption plan. A 2013 risk profile for St. Kitts and Nevis from the Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility (CCRIF) estimated average annual losses of $15.1 million from hurricanes.79Note: CEAC Solutions Ltd. “Road Sector Hazard Risk & Vulnerability Assessment Report St. Kitts and Nevis (Revised Report).” Government of St. Kitts and Nevis. December 5, 2019.

St. Kitts and Nevis has historically had one of the smallest informal economies in the region.80Note: Vuletin, Guillermo. “Measuring the Informal Economy in Latin America and the Caribbean.” IMF Working Paper. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2008/wp08102.pdf Experts rated the informal economy as a medium-high risk (6.15), however, and interviews noted the challenges of reaching informal workers with government policy and support.81Note: Interview with representatives from the Ministry of Environment and Climate Action. The lack of integration into formal economic institutions of workers and firms operating in the informal economy makes it difficult to effectively incorporate them into climate resilience planning and recovery efforts.

Lower risk scores in resilience of airports (4.16), water distribution infrastructure (3.96), and the power grid (3.78) demonstrate that St. Kitts and Nevis has been successful in building resilience in much of the country’s essential infrastructure. Interviews noted that part of the power grid has been buried to limit its vulnerability to high winds and facilitate faster service restoration in the event of an outage.82Note: Interview with representatives from the St. Kitts Electricity Company. Medium-high risk scores in resilience for roads (5.14) and proportion of wastewater treated (5.09) suggest that these are two areas that require further attention and resources. A recent assessment found that nearly 40% of coastal roads in St. Kitts require major rehabilitation, including most of those in Basseterre.83Note: CEAC Solutions Ltd. “Road Sector Hazard Risk & Vulnerability Assessment Report St. Kitts and Nevis (Revised Report).” Government of St. Kitts and Nevis. December 5, 2019. Nearly 90% of household wastewater in St. Kitts and Nevis is stored in septic tanks,84Note: “SDG Goal 6 Monitoring: 6.3.1 Safely Treated Household Wastewater: Saint Kitts and Nevis: 2020 Country Estimate”. WHO and UN-HABITAT. leaving it vulnerable to leaking into groundwater supplies or contaminating coastal ecosystems. Most types of physical infrastructure in St. Kitts and Nevis are located within two kilometers of the coast, part of the country’s highly developed shoreline (6.03) that is at risk from extreme weather events such as flooding, hurricanes, and storm surge.85Note: Government of St. Kitts and Nevis. “The National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy for Saint Christopher and Nevis.” Additionally, population growth in Basseterre has driven increased development on hazard-prone areas, such as coastal flood plains or steep slopes, increasing the risks of coastal erosion (6.04), flooding (5.84) and potential contamination of freshwater sources (6.03).

One way to further improve the climate resilience of Basseterre’s power grid while also reducing vulnerability to global commodity price swings is to encourage the growth of renewable energy (6.69) on the island. While electricity provision (1.81) is nearly universal, renewable energy currently accounts for less than five percent of electricity output and less than two percent of total energy consumption.86Note: “Renewable electricity output (% of total electricity output) - St. Kitts and Nevis.” World Bank Open Data. Accessed September 7, 2022. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EG.ELC.RNEW.ZS?locations=KN and “Renewable energy consumption (% of total final energy consumption) - St. Kitts and Nevis.” World Bank Open Data. Accessed September 7, 2022. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EG.FEC.RNEW.ZS?locations=KN Renewables, particularly in combination with microgrids, can reduce single-point-of-failure risks that characterize traditional centralized power grids.87Note: “Microgrids for disaster preparedness and recovery.” IEC Market Strategy Board. https://www.preventionweb.net/files/42769_microgridsfordisasterpreparednessan.pdf This can be particularly valuable during recovery from extreme weather events, as distributed energy storage can also reduce the time it takes for first responders to begin recovery efforts.88Note: “The Role of Energy Storage in Disaster Recovery and Prevention.” NEMA. https://www.nema.org/storm-disaster-recovery/microgrids-and-energy-storage/the-role-of-energy-storage-in-disaster-recovery-and-prevention Increased renewable generation can also reduce spending on imported fossil fuels, which in 2015 accounted for four percent of GDP annually,89Note: “Energy Snapshot: The Federation of Saint Christopher and Nevis.” NREL Energy Transition Initiative. March 2015. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy15osti/62706.pdf and potentially thereby reduce debt levels (5.38). The National Energy Policy of 2011 supports this vision, in pursuit of the goal to “become the smallest green nation in the Western Hemisphere,” with a more diversified energy sector that makes greater use of renewable resources. 90Note: “National Energy Policy of St. Kitts and Nevis.” Government of St. Kitts and Nevis. April 25, 2011. http://www.oas.org/en/sedi/dsd/Energy/Doc/NationalEnergyPolicyStKittsandNevis.pdf Interviews cited government efforts to boost residential rooftop solar and increase the adoption of electric vehicles.91 Note: Interview with representatives from the St. Kitts Electricity Company.

Basseterre: Financial Risk

Political Risk

The political risk that Basseterre faces is distributed across the risk area’s three constituent categories, all of which have nearly equal average scores. These averages, however, contain considerable variation in the indicator scores, slightly more than half of which are scored as medium-high risks. The highest risk score is the capacity of current disaster response (7.29), highlighting the institutional and resource constraints faced by St. Kitts and Nevis. Lower scores for indicators such as social tension (4.12), civil unrest (3.34), and rule of law (2.71), suggest that the country has a strong foundation on which to strengthen climate resilience.

- In GOVERNANCE, the capacity of current disaster response (7.29) and national climate adaptation plan (5.60) were scored medium-high risks. Investment in climate resiliency was scored a medium risk (3.15), suggesting institutional capacity and resiliency planning may be higher priorities than disaster response. Additional medium-high risk scores for ethics enforcement (6.18) and perceived transparency (6.05) highlight additional institutional concerns. While voter turnout (3.23) was not a major concern, the medium-high risk score for civil society participation (5.62) may offer avenues for deeper engagement with the population around reducing climate risks.

- The SOCIAL AND DEMOGRAPHICS, category reflects potential concerns around ongoing, long-term population changes, including a growing dependent population (6.37), a rising population of international migrants (6.16), and recent population growth in Basseterre. The medium-high risk score for poverty (5.39) highlights additional risks, while the lower risk score for literacy and numeracy (3.43) reflects successes in extending basic education services.

- In STABILITY, medium-high risk scores reflect the importance of the tourism (6.60) and port/shipping (5.68) sectors in the national labor force, echoing risks identified in the Major Industries category. Lower risk scores for social tension (4.12) and civil unrest (3.34) highlight the country’s peaceful public space.

Basseterre, like other coastal cities in the Caribbean facing climate change are witnessing risks from tropical storms, coastal and inland flooding, rising sea levels, drought, and extreme heat, all of which will likely worsen in the coming years putting put citizens and businesses at greater risk. In response, the national government has proposed several climate adaptation plans (5.60) including a comprehensive national adaptation strategy and sector-specific plans to build resilience in areas such as water infrastructure92Note: “Vulnerability Assessment and Water Utility Adaptation Plans St Kitts and Nevis – Water Sector Adaptation Plan.” and coastal roads.93Note: CEAC Solutions Ltd. “Road Sector Hazard Risk & Vulnerability Assessment Report St. Kitts and Nevis (Revised Report).” Government of St. Kitts and Nevis. December 5, 2019. Implementation of identified adaptation measures, however, remains a challenge, with fewer than 50% of the adaptation actions implemented through 2021.94Note: “St. Kitts and Nevis: Updated Nationally Determined Contribution.” Local experts raised the lack of funding and insufficient technical and human resources as consistent barriers to implementation as well as the lack of a centralized climate planning and adaptation authority. This was a conclusion echoed by a recent World Bank report on disaster preparedness in St. Kitts and Nevis and four other eastern Caribbean states.95Note: “Upgrading Caribbean Disaster Preparedness and Response Capacities: Caribbean Nations Work Together for Regional Resilience.” World Bank Group. January 15, 2021. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/379651610738611722/upgrading-caribbean-disaster-preparedness-and-response-capacities-caribbean-nations-work-together-for-regional-resilience The same kind of institutional capacity shortcomings and resource shortfalls constrain the capacity of the country’s disaster response system (7.29), which is led by the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA).

Institutional challenges may be compounded by concerns around governmental transparency (6.05) and insufficient ethics oversight (6.18). Such worries may have several sources. The first is the country’s long-running Citizenship by Investment (CIB) program which offers citizenship to individuals who invest significant sums.96Note: For more information: http://stkitts-citizenship.com/ Prime Minister Harris vowed to clean up the program in 2015 amid concerns about a lack of oversight and scrutiny of applicants,97Note: Crowcroft, Orlando. “St Kitts and Nevis: New anti-corruption leader of Caribbean island vows to clean up trade in passports for super-rich.” International Business Times. July 21, 2015. https://www.ibtimes.co.uk/st-kitts-nevis-dubious-trade-passports-super-rich-target-new-anti-corruption-leader-tiny-1511699 and the government introduced additional reforms in 2020.98Note: “Freedom in the World 2021: St. Kitts and Nevis”. Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/country/st-kitts-and-nevis/freedom-world/2021 Separately, two members of the National Assembly and members of the government were convicted of misappropriating client funds.99Note: “High Court Judge refuses to set aside default judgment in US$460,000 case involving Lindsay Grant and Jonel Powell.”. SKN Web News. November 14, 2019. http://sknwebnews.com/high-court-judge-refuses-to-set-aside-default-judgment-in-us460000-case-involving-lindsay-grant-and-jonel-powell/ Public procurement rules lack regulations, bid evaluations and contract negotiation processes “are untransparent and appear open to influence” according to a 2019 OECD report.100Note: “Assessment of St. Kitts & Nevis’ Public Procurement System.” OECD Methodology for Assessing Procurement Systems. 2019. https://www.oecd.org/countries/saintkittsandnevis/MAPS-assessment_report-SKN.pdf The rules for implementing the code of conduct for public officials and financial disclosure guidelines have not yet been established and the Freedom of Information Act has yet to be implemented because of inadequate resources.101Note: Freedomhouse – https://freedomhouse.org/country/st-kitts-and-nevis/freedom-world/2021,retrieved 2022- 06-11. The media and private citizens in St. Kitts and Nevis have reported government corruption as a problem.102Note: https://www.state.gov/report/custom/8538e36df6/, retrieved 2022- 06-11. These shortcomings reduce public trust in government while increasing the cost and reducing the effectiveness of public investments in climate resilience.

The population of Basseterre specifically, and St. Kitts and Nevis more generally, are also going through several long-term shifts that, while not rated as among the highest vulnerabilities the city faces, may become more acute in the future. Chief among these is the aging of its population, captured in the medium-high risk score for Dependency Ratio (6.37). The median age of 36.5 is neither particularly old nor young compared to the rest of the Caribbean,103Note: “St. Kitts and Nevis.” CIA World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/saint-kitts-and-nevis but the country will face increasing risks as the population ages. These include lower tax revenues, higher spending on social insurance and healthcare (projected to grow by ~50% between 2018 and 2050),104Note: “IHME Country Profiles: St. Kitts and Nevis.” IHME. https://www.healthdata.org/saint-kitts-and-nevis and increased difficulty in evacuating around extreme weather events.

The number of international migrants in St. Kitts and Nevis (6.16) has increased since the 1990s, rising from 3,210 (8% of the population) in 1990 to 7,245 (14.8% of the population) in 2010. In the following ten years, growth slowed, with the number of migrants remaining constant at 7,725 by 2020, accounting for just 14.5% of the population.105Note: “International Migrant Stock 2020: Destination”. UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. There are concerns, however, that the increased impact of extreme weather events in the Caribbean may result in a greater number of people displaced by climate disasters who may become migrants arriving in St. Kitts and Nevis in the coming years.106Note: Serraglio, Diogo Andreola, Stephen Adaawen, and Benjamin Schraven. “Migration, Environment, Disaster and Climate Change Data in the Eastern Caribbean: Saint Kitts and Nevis Country Analysis.” International Organization for Migration. https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/MECC-Saint-Kitts-and-Nevis-Country-Report.pdf Experts noted the high incidence of migrants, particularly the elderly, living in the Irishtown and Newtown neighborhoods are highly vulnerable. These migrants may have difficulty securing employment in the formal economy, and be forced into the informal economy, with its attendant challenges.107Note: Interview with representatives from the Ministry of Environment and Climate Action.

The poverty (5.39) and urbanization (5.97) rates were also scored medium-high risks. This is in part to spending on social security, health, and education that has accounted for up to 20 percent of GDP.108Note: “Saint Kitts and Nevis.” Pan American Health Organization. https://paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2012/2012-hia-saintkittsandnevis.pdf The poverty rate in St. Kitts fell from 30.5% in 2000, to 23.7% in 2008 and to 21.8% in 2022109Note: Saint Kitts & Nevis: Country Profile https://reliefweb.int/report/saint-kitts-and-nevis/saint-kitts-nevis-country-profile-may-2022, retrieved 2022-10-04. , with extreme poverty falling from 11% to 1.4% over the same period.110Note: Francis Jones, Catarina Camarinhas, and Lydia Rosa Gény. “Implementation of the Montevideo Consensus on Population and Development in the Caribbean.” ECLAC Subregional Headquarters for the Caribbean. https://caribbean.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/S1801148_en.pdf More than half of the poor live in the parishes of St. George Basseterre, St. Mary, and St. John.111Note: “Saint Kitts & Nevis Country Profile.” UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). The national government introduced the Poverty Alleviation Programmer in 2018, providing a monthly $500 stipend for the country’s poorest citizens. It expanded the program during the COVID-19 pandemic as part of its effort to mitigate economic suffering and stimulate the economy.112Note: Welsh, Olivia (2020) “Poverty Eradication in Saint Kitts and Nevis.” The Borgen Project. https://borgenproject.org/poverty-eradication-in-saint-kitts-and-nevis/ St. Kitts and Nevis has also made progress in improving health, particularly in reducing maternal mortality and communicable disease mortality.113Note: “St. Kitts and Nevis: Country Cooperation Study”. World Health Organization. May 1, 2018. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-CCU-18.02-St.KittsandNevis Non-communicable diseases such as cancer, diabetes, and heart disease are now the leading causes of mortality, though chikungunya and Zika were introduced into the country in 2014 and 2016, respectively.114Note: Ibid. The country avoided any deaths from COVID-19 until June 2021.115Note: “COVID-19: St. Kitts and Nevis”. World Health Organization. Accessed October 27, 2022. https://covid19.who.int/region/amro/country/kn

The urbanization of Basseterre is another important issue. The city’s population grew from approximately 11,400 people in 2011 to roughly 14,000 people in 2018,116Note: CIA World Factbook. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/saint-kitts-and-nevis/#people-and-society reversing the declining population trend of the preceding decade.117Note: “Parish Size, Population and Density 1991-2011”. St. Kitts and Nevis Department of Statistics, Ministry of Sustainable Development.” https://www.stats.gov.kn/topics/demographic-social-statistics/population/parish-size-population-and-density-1991-2011/ This is an average population growth rate of approximately 2.98%, approximately three times that of the country.118Note: “Population, total - St. Kitts and Nevis.” The World Bank. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=KN Furthermore, most predictions indicate that the population of Basseterre will continue to grow until 2030. This type of population growth has led people, including transient and at-risk migrant populations, to encroach on hazard-prone areas, such as coastal flood plains or steep slopes, to construct settlements, further exacerbating the risks associated with coastal erosion (6.04), water quality (6.03), waste and water management and flooding (5.84).

The growth of the Kittitian tourism industry has been a major driver in the rise of Basseterre’s population. There had been about 4,800 people, accounting for approximately 9% of the national population, working in the travel and tourism sector in 2019 with center at Basseterre, before the COVID-19 pandemic.119Note: https://knoema.com/atlas/Saint-Kitts-and-Nevis/topics/Tourism/Travel-and-Tourism-Direct-Contribution-to-Employment/Direct-contribution-of-travel-and-tourism-to-employment, retrieved 2022- 06-11. That same growth, however, is a source of vulnerability in Basseterre. Coastal and marine tourism activities are made up the volume of the tourism industry in St. Kitts. These activities, however, are vulnerable to disruption due to months-long closures of beaches and resorts for reconstruction due to extreme weather events. This type of damage is not limited to a severe hurricane or direct hits. For example, Hurricane Omar, a category 3 hurricane that did not hit St. Kitts and Nevis directly, severely damaged the Four Seasons hotel, which closed for more than one year.120Note: “St. Kitts and Nevis.” University of the West Indies. https://www.uwi.edu/ekacdm/saint-kitts-and-nevis?page=1

Basseterre: Political Risk

The Status of Resilience Planning in Basseterre

The government of St. Kitts and Nevis has taken significant steps to support resilience planning and development and integrate it into the country’s policy framework as well as its financial and technical support programming. The cornerstone of this effort is the National Climate Change Policy, adopted in 2017, which highlights sector-specific vulnerabilities and provides guidance on addressing them. This guidance was further developed in the National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy and Action Plan of 2018, which encompasses agriculture, coastal and marine ecosystems, forest and terrestrial ecosystems, finance and banking, human health, infrastructure and physical development, tourism, and water. In 2021, the government submitted its Revised National Determined Contribution under the Paris Agreement, which explicitly outlines adaptation options across all sectors and recognizes the importance of loss and damage.

Critically, planning to strengthen resilience in Basseterre has recognized the importance of integrating planning across the land and seascape as well as integrating urban and marine spatial planning. The former is exemplified by the Integrated Water, Land and Ecosystems (IWEco) project, funded by the Global Environment Facility. Under the IWEco, activities have begun to reduce and reverse land degradation, particularly in the College Street Ghaut area. The project has implemented land degradation control measures by establishing contour hedges along the upper banks of the ghaut, planting vetiver grass stabilizing, and maintaining existing retaining walls and bridges. The Urban Resilience Plan calls for the implementation of the 2021 Coastal Master and Marine Spatial Plan as part of reducing the vulnerability of Basseterre to extreme weather events. The Urban Resilience Plan also calls for improved management and protection of the Basseterre Valley Watershed, the ghaut system, and the Basseterre Valley Aquifer from environmental degradation, climate change, and pollution. The Coastal Master and Marine Spatial Plan includes provisions aimed at preventing coastal erosion, exploring coastal and offshore renewable energy resources, restoring coastal bluffs, expanding conservation areas, restoring coral reefs and other coastal and marine habitats, and implementing integrated management of watersheds and coastal areas.

The government has also proposed sector-specific climate change adaptation plans, which include measures to:

- Upgrade infrastructure, principally housing, through steps such as replacing wooden buildings with concrete structures and enforcing strong building codes

- Reduce freshwater demand by reducing leakage and unauthorized usage, educating consumers in water conservation, and improving water efficiency

- Update the 2018 Investment Plan for Climate Resilient Water Services for St. Kitts and Nevis to incorporate new and emerging climate challenges, adaptation actions and priorities

- Invest in energy efficiency and renewable energy, including retrofitting solar and wind installations with more efficient pumps, to reduce carbon emission and electricity costs

- Create a sustainable, resilient, and inclusive agricultural system through the St. Kitts and Nevis Agricultural Transformation and Growth Strategy 2022-2031

- Improve road infrastructure resilience, especially in the Fortlands and Bay Road areas, by reducing coastal erosion.

St. Kitts and Nevis has also worked closely with the Green Climate Fund (GCF) to strengthen institutional capacity, governance, and planning and programming frameworks. Work with the GCF is coordinated through the National Designated Authority (NDA), which is housed in the Department of Economic Affairs & PSIP (NDA), Ministry of Sustainable Development. The NDA is also responsible for providing broad strategic oversight of the GCF’s activities in the country along with communicating the country’s priorities for financing low-emission and climate-resilient development. Work with the GCF has included drafting a National Development Plan for 2022-2037 aimed at integrating climate resilience into economic development planning, plans to conduct Enhanced Vulnerability and Capacity Assessments in two communities, an operational plan for the Meteorological Office, and improved disaster forecasting, early warning, management, and response.

However, key gaps persist in St. Kitts and Nevis’ resilience planning. First, existing plans overlook wastewater management in Basseterre. Second, reliable and consistent data from both the public and private sectors is often lacking, in part because there is no established coordination mechanism to share information between and across the public and private sectors. Information sharing is currently conducted in an ad-hoc manner. Interviews noted that this lack of reliable data hampered effective integrated management systems for climate risks, land degradation, and protection of biological diversity. Finally, a lack of funding was often cited as a key barrier, contributing to a state in which less than 50% of action identified in the National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy have been implemented or integrated into annual operational plans.

Priority Recommendations to Build Resilience

Although the Governments of St. Kitts and Nevis has employed significant plans, they should still contend with the growing risk of climate change. Economic reliance on key blue economy sectors, for example, fisheries, tourism, and renewable energy dependence etc., were all prominent issues in the CORVI risk profiles. Experts also highlighted problems related to strengthening emission efficiency. A lack of coordination and integration of public and private sectors was identified throughout the research process.

With support from the public and private sectors, the Basseterre decision-makers is well placed to overcome statute of limitations and provide necessary leadership on climate change, build integrated regional climate database system for strategic planning, enhance varied renewable energy sectors, and improve sustainable blue economy plans and activities. By strengthening ecosystem and financial resilience, Basseterre can mitigate the threat posed by climate and ocean risks and build a resilient and sustainable future.

Increase Coordination and Planning Between the Government and Private Sector

Improving disaster management capacities is vital for the central government. However, addressing climate change and disaster impacts requires improved strategic planning and prioritized implementation integrated across multiple ministries and the private sector. For instance, the ability to resume critical business functions post-disaster was a key gap noted by several experts, linking to higher risk indicator scores for capacity of disaster response, level of perceived transparency within government, high dependence on coastal tourism and ports and shipping industries, and commercial infrastructure at risk. Water management issues, both stormwater and wastewater, and flood risk may disproportionately impact transient, migrant, and other vulnerable populations, reflecting the need to prioritize the implementation of climate resilient water services.

The first step may be to establish a permanent climate coordination mechanism—developing or repurposing a working group or committee that includes participation from government members, key industries, and civil society—to prioritize necessary actions to proactively address the most pressing climate risks, including those identified in this assessment; improving water infrastructure and stormwater management and reducing impacts on vulnerable populations, and establishing a city- or island-wide business resumption plan, potentially including table-top exercises.

To support this effort, capacities in collecting and managing actionable data and information could be improved and streamlined. This is critical, as effective data collection and management systems is key to policy making, climate adaptation, and disaster preparedness, response and recovery.121Note: World Bank Group, (2021), Upgrading Caribbean Disaster Preparedness and Response Capacities: Caribbean Nations Work Together for Regional Resilience (English), Washington, D.C., USA. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/379651610738611722/Upgrading-Caribbean-Disaster-Preparedness-and-Response-Capacities-Caribbean-Nations-Work-Together-for-Regional-Resilience, retrieved 2022-06-24. Based on the former data, NEMA could establish an official database on disaster issues that can be readily accessed by any relevant government agency and interested party/ stakeholders. In order to enhance marine biodiversity conservation and sustain ecosystem diversity, long-term marine ecological monitoring is also essential. Through data collection, the database system could build a baseline and provide scientific evidence for spatiotemporal variations (ex., annual sea temperature, historical biodiversity index, special event record etc.,) and managing human impacts such as coastal development.

Promote Renewable and Distributed Energy Capacity

Indicators such as renewable energy share in total energy consumption in Basseterre received a medium-high risk score underscoring the need to reduce the country’s reliance on fossil fuels. This reliance has left St. Kitts and Nevis at the whim of often rapid and major fluctuations in global oil markets, which can contribute to rising external deb.122Note: Department of Investment Services, Ministry of Economic Affairs, (2012),"Investment Guide to Saint Christopher and Nevis, “https://www.taiwanembassy.org/kn/post/1184.html, retrieved 2021-09-21. In addition, microgrids can improve the stability of the power grid,123Note: “Hazard Mitigation Assistance Grant Funding for Microgrid Projects”. Federal Emergency Management Agency. June 25, 2021. https://www.fema.gov/fact-sheet/hazard-mitigation-assistance-grant-funding-microgrid-projects improve grid resilience during extreme weather events,124Note: Javier Rúa Jovet and Tierney Sheehan. “Hurricane-Proof Energy for Puerto Rico”. RMI. https://rmi.org/hurricane-proof-energy-for-puerto-rico/ and facilitate recovery efforts after a storm.125Note: Chad Abbey, et. al. “Powering Through the Storm: Microgrids Operation for More Efficient Disaster Recovery”. IEEE. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/6802506 The National Energy Policy of 2011 has already established the goal of becoming the smallest green nation in the Western Hemisphere, and the country’s revised NDC set the target of generating 100% of its electricity from renewable energy.

The government has taken important steps towards these goals, including beginning construction on the largest solar farm and battery storage facility in the Caribbean and implementing renewable energy tax credits. However, there are additional steps that could accelerate the transition to a renewable and distributed electricity grid. First, the government could work with the St. Kitts and Nevis Chamber of Industry and Commerce to increase awareness of renewable energy options, identify key obstacles to the growth of renewable industry, and streamline permit approvals. Second, the government could consider implementing additional financial incentives, such as feed-in tariffs and net metering. Third, the government could work with the St. Kitts Electricity Company and major electric power consumers to identify critical power loads, such as hospitals, that should be prioritized for continuous power supply and design a strategy to ensure continuity and enhance grid resiliency.126Note: Bunker, Kaitlyn, Kate Hawley, and Jesse Morris. “Renewable Microgrids: Profiles from Islands and Remote Communities Across the Globe”. Rocky Mountain Institute. November 2015. “http://www.rmi.org/islands_renewable_microgrids” Finally, renewable energy stakeholders from the public and private sectors, including project developers, investors, and the government, could consider taking advantage of investment and asset management platforms with a regional or global scope to reduce costs and expand the potential investment pool.

Increase the Sustainability of the Blue Economy and Promote Sustainable Economic Development

High risk scores for indicators related to coastal tourism and fisheries illustrate the island’s connection to healthy ecosystems and the blue economy. Coastal tourism provides jobs and revenues—approximately one-third of GDP—for residents of St. Kitts and Nevis. Fisheries is the highest-scoring risk category in the assessment, reflecting the significance and vulnerability of this sector. The potential for increasingly stronger hurricanes hitting the island also increases risk to these critical industries. The vulnerability of Basseterre is clearly linked to the health of the blue economy. The Kittitian government could work with private partners and civic society (e.g., the Sustainable Destination Council) to enhance and expand efforts to increase the sustainability of the blue economy and promote sustainable economic development.

For instance, opportunities exist to focus environmentally sustainable redevelopment along the Basseterre seawall area and historic Basseterre, integrating natural and man-made infrastructure to enhance the protective capacity of the seawall from hurricanes, and providing an enhanced tourism experience. Improving the sustainability of these blue economy sectors would reduce potential risks, both to facilities and people who rely on the industry as a significant source of income. In addition, the government of St. Kitts and Nevis should balance the development of major industries and environmental sustainability (e.g., reduce the shoreline construction by tourism sectors) and actively implement of fisheries and ecosystem management regulations (e.g., the Marine Management Area) to improve the health of coastal ecosystems.

Appendix

Organizations Interviewed

AVEC

Eastern Caribbean Central Bank

Electricity company limited

Fashion designer & retail business owner

Florida Memorial University

Jenkins Ltd

Kajola Kristada Ltd.

Kenneth’s Diving Center

Maitland & Maitland Associate

National Disaster Coordinator

National Emergency Management Agency

National Emergency Operations Center

Spice Mill Restaurant

S L Horsfords Ltd

St. Kitts Sea Turtle Monitoring Network

The office of St. Kitts Metservice

White Development Corporation

Organizations Surveyed

Acorus Services Ltd.

Agrimatco

C&C Trading, Ltd.

Capital Realty

Clarence Fitzroy Bryant College

Department of Environment, Ministry of Environment and Climate Action

Department of Maritime Affairs, Ministry of Public Works, Utilities, Transport & Posts

Department of Statistics, Ministry of Sustainable Development

DK Designs

Ible Real Estate

International Union for the Conservation of Nature

Ministry of Environment and Climate Action

Ministry of Finance

Ministry of Sustainable Development

Ministry of Tourism & Transport

National Emergency Management Agency

People Employment Program

SKN Marine Surveying & Consultancy

Sol EC, Ltd. (Petroleum)

St. Kitts & Nevis Coast Guard

St. Kitts & Nevis Customs and Excise Department

St. Kitts & Nevis Department of Marine Resources

St. Kitts Electricity Company, Ltd

Notes

- 1Note: Saint Kitts and Nevis-The World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/saint-kitts-and-nevis/#people-and-society, retrieved 2021-09-12.

- 2Note: OECS, (2021),”Country analysis: resilience to climate change at a glance Saint Kitts and Nevis.”

- 3Note: Food and Agriculture Organization. “Fish and Seafood Production.” Our World In Data. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/fish-seafood-production?tab=chart®ion=NorthAmerica&country=~KNA

- 4Note: Government of Saint Kitt and Nevis, (2021), "Marine Resources."

- 5Note: Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism (2021) CRFM Statistics and Information Report - 2020

- 6Note: UN Comtrade. “Saint Kitts and Nevis trade in fish, crustaceans, molluscs, and aquatic invertebrates.” https://dit-trade-vis.azurewebsites.net/?reporter=659&type=C&commodity=03&year=2017&flow=2

- 7Note: Ritchie H and RoserM, (2019), "Seafood Production," Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: https://ourworldindata.org/seafood-production [Online Resource].

- 8Note: Morgan, Rayne. “St. Kitts & Nevis workers turn to fishing amid tourism shutdown.” Caribbean Employment Services Inc., September 16, 2021. https://caribbeanemployment.com/caribbean-jobs-and-employment/st-kitts-nevis-workers-turn-to-fishing-amid-tourism-shutdown-says-doctor-marc-williams-director-department-of-marine-resources-maritza-queeley-port-state-control-officer/?noamp=mobile

- 9Note: Ocean Health Index. “2021 Index: Food Provision: Wild Caught Fisheries”. https://oceanhealthindex.org/global-scores/

- 10Note: Interview with food service industry, St. Kitts.

- 11Note: Interview with local retail industry, Basseterre, St. Kitts and Nevis. March 1, 2022.

- 12Note: Sea Around Us, "Catches by Reporting status in the waters of Saint Kitts & Nevis," https://www.seaaroundus.org/data/#/eez/659?chart=catch-chart&dimension=reporting-status&measure=tonnage&limit=10, retrieved 2021-09-22.

- 13Note: European Parliament (2022), "Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing."

- 14Note: Government of Saint Kitt and Nevis, (2015) "National plan of action to prevent, deter and eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing."