| Capital | Phnom Penh |

| Area | 181,030 km² |

| Population | 16,718,971 (2020 estimate) |

| GDP | USD 25.291 billion |

| GDP Growth Rate Projections | 1.9% annually in 2021, usually around 7% pre-pandemic |

| Inequality (Gini Coefficient) | 36.6 (medium) |

| Human Development Index (HDI) | 0.594 (2019) |

| World Bank Income Status | Lower middle-income status |

| Key export | clothing, timber, rubber, rice, fish, tobacco, footwear |

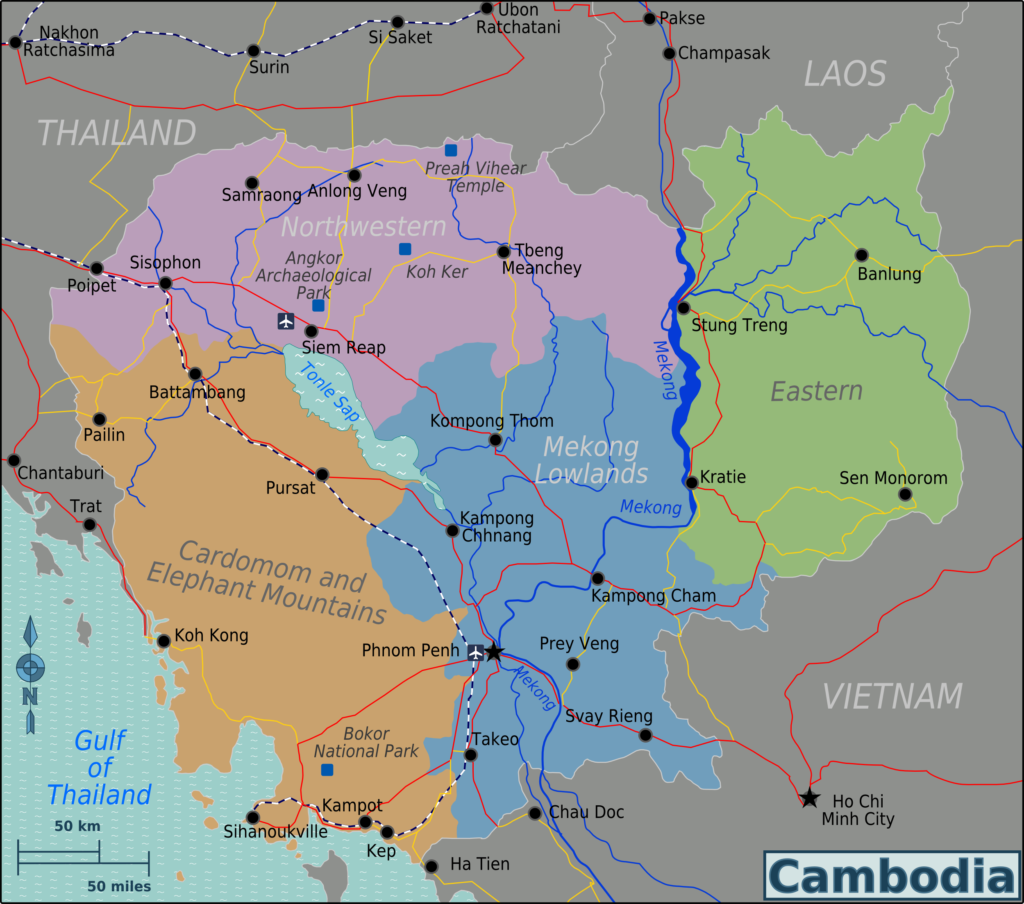

With falling poverty rates and high economic growth, Cambodia reached lower middle-income status in 2015 and aspires to attain upper middle-income status by 2030.1World Bank, “The World Bank in Cambodia”, World Bank, retrieved on 27 July 2020. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/cambodia/overview However Cambodia will likely remain a least developed country until the mid-2020s and in 2019, Cambodia’s National Council for Sustainable Development declared that the impacts of climate change will likely delay Cambodia’s attainment of upper middle-income status.2Ministry of Economy and Finance and National Council for Sustainable Development, Addressing Climate Change Impacts on Economic Growth in Cambodia, 2019, page 43. Upward growth needs to be supported through further energy and transport infrastructure investments, which have been developing rapidly but from a low starting point. A significant investment gap remains, and a much larger proportion of GDP spent on infrastructure is needed.

Cambodia’s Infrastructure Gap

A 2016 study by the Asian Development Bank indicates that Southeast Asia needs approximately $2.7 trillion invested in energy, transportation, telecommunications, and water infrastructure by 2030.3Asian Development Bank, Meeting Asia’s Infrastructure Needs, Asian Development Bank, 2017, pages xiv and 43. This calculates to approximately 6% of the region’s annual GDP, with actual needs higher in less developed countries. Energy and transportation account for more than 86% of the total projected needs, rising to 88% if climate considerations are taken into account.4ADB, Meeting Asia’s Infrastructure Needs, 2017, page 45. In Cambodia, the annual national budget and private infrastructure investment combined only account for approximately 2.5% of national GDP, leaving a significant gap.5Infrastructure Outlook, “Cambodia“, Infrastructure Outlook, retrieved on 6 June 2020. https://outlook.gihub.org/countries/Cambodia

A significant expansion of power generation capacity is required to meet Cambodia’s rapidly growing demand for electricity. While the Kingdom’s transportation network is evolving and expanding quickly, it lacks connectivity to many key economic centers domestically and also cross-border connections to regional hubs like Ho Chi Minh City and Bangkok.

Cambodia’s foreign direct investment in 2019 totaled nearly US $3.6 billion. The National Bank of Cambodia reported that 43% of this investment came from China, up from 15% of total FDI in 2017 and far higher than other major investors like South Korea (11% of FDI in 2019), Vietnam (7%), Singapore (6%), and Japan (6%).6Xinhua, “Cambodia attracts 3.6-bln-USD FDI in 2019, 43 pct from China,” Xinhua, January 10, 2020, accessed November 2, 2020, at http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-01/10/c_138694282.htm. Prior to the coronavirus pandemic, the NBC forecasted that the inflow of FDI into the country would rise 10 percent in 2020, reaching 3.95 billion U.S. dollars.7Xinhua, “Cambodia attracts 3.6-bln-USD FDI in 2019., 43 pct from China.” However, following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic FDI inflows, tourism, and other key economic engines have stalled. The value of approved FDI projects contracted by more than 50% in early 2020, and overall Cambodia’s economy is expected to contract between 1 and 2.9 percent in 2020.8World Bank, “COVID-19 epidemic poses greatest threat to Cambodia’s Development in 30 Years,” May 29, 2020, accessed November 4, 2020, at https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/05/29/covid-19-coronavirus-epidemic-poses-greatest-threat-to-cambodias-development-in-30-years-world-bank; The World Bank, Cambodia Economic Update: Cambodia in the Time of COVID-19, May 2020, page 17, at http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/357291590674539831/pdf/CEU-Report-May2020-Final.pdf.

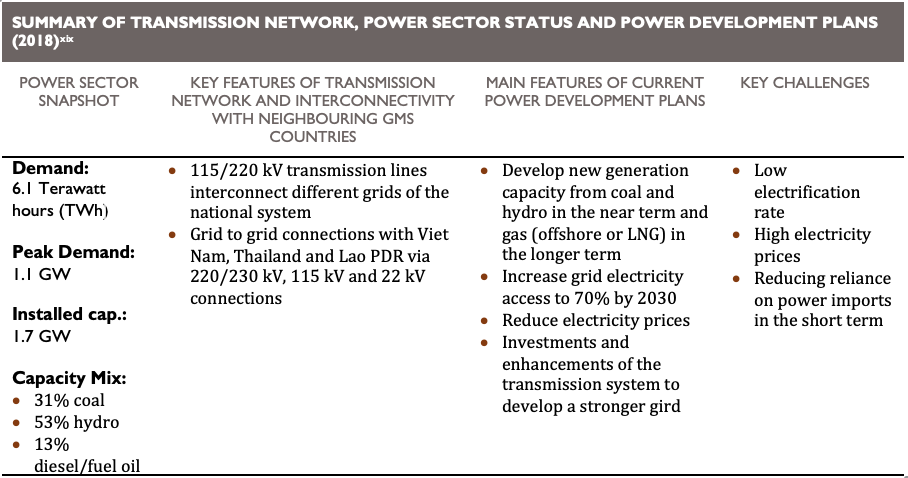

Energy Sector Overview

The Mekong Infrastructure Tracker shows that Cambodia had 2441 MW of installed power generation capacity in 2020, with 1341 MW of that (55%) coming from hydropower dams and 650 MW (27%) coming from coal, and 305 MW (12%) from solar. Cambodia’s rapid electricity demand, which has averaged approximately 20% annually since 2010, is largely responsible for the push for hydropower development.9World Wild Fund. Power Sector Vision: Towards 100% Renewable Electricity by 2050. Cambodia Report. May 2016. Page 5. http://wwf.panda.org/what_we_do/where_we_work/greatermekong/our_solutions/2050powersectorvision/. Experts from the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) estimate 150-200% higher cumulative growth in energy demand through 2025.10IRENA, Renewable Energy Market Analysis: Southeast Asia, 2018, page 48. This demand growth has resulted in a rapid expansion of Cambodia’s installed capacity in order to avoid shortages.

But recent droughts, particularly in the Mekong Basin, have discouraged further growth in hydropower development as projects are not able to generate reliable power to meet growing demand. Unpredictable swings in weather patterns in addition to a growing concern of the impact of hydropower on the country’s fisheries sectors has driven a rethink in long term and short-term strategies for power generation expansion in Cambodia. Notably, the Cambodian government halted the proposed Sambor and Stung Treng dams; environmental impact studies have demonstrated that the dams would obstruct all connectivity between the Tonlé Sap and upper Mekong River, in addition to devastating local ecologies and severely hampering sediment distribution.

To address immediate electricity shortages, Cambodia has built a few medium-scale solar plants with more in the pipeline as solar tariffs continue to fall both globally and in Cambodia. Since the first pilot solar project came online in 2017, 305 MW of solar projects have become operational and 710 MW are under further development. Cambodia’s urgent response to hydropower’s inefficiencies has included a quick expansion into fossil fuel solutions through the construction of several new coal and heavy fuel plants along the country’s coast and a recently-signed MOU for the import of 2,400 MW of power generated from two new thermal plants in southern Laos.11Thou Vireak, “Kingdom okays 2,400 MW power purchase from Laos,” The Phnom Penh Post, September 11, 2019, accessed November 4, 2020, at https://www.phnompenhpost.com/business/kingdom-okays-2400mw-power-purchase-laos. Cambodia also signed an MOU to import 200 MW of hydropower capacity from the Don Sahong Dam on the Mekong mainstream in southern Laos near the Cambodian border.

The Royal Government of Cambodia sets targets for the energy sector in the National Strategic Development Plan (NSDP). NSDP prioritizes increasing electricity supply capacity, reducing electricity tariffs to an appropriate level, and strengthening institutions to manage the energy industry.12ADB, “Energy Sector Assessment, Strategy, and Road Map”, ADB, December 2018, retrieved on 7 June 2020. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/institutional-document/479941/cambodia-energy-assessment-road-map.pdf Rural electrification, reduction of high tariff rates, and diversification of the electricity supply are three principle challenges for Cambodia’s electricity sector.

Phnom Penh and other urban electricity demand centers enjoy a high electrification rate (approximately 97%), but the national average electrification rate drops to about 50% when including rural areas.13International Energy Agency, Southeast Asia Energy Outlook 2017, IEA/OECD, 2017, page 104. The government’s 2014 – 2018 National Development Plan included a commitment to speed up electrification efforts to ensure universal access to electricity by 2020.14Royal Government of Cambodia, National Strategic Development Plan 2014 – 2018, July 17, 2014, page 156, at http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—asia/—ro-bangkok/—sro-bangkok/documents/genericdocument/wcms_364549.pdf But improvements to grid access are slowed by the remote nature of unconnected villages and a lack of investment in micro-grids to serve remote communities due to issues with the regulatory regime for micro-grid investment.

In cooperation with the European Union (EU), Cambodia’s Ministry of Mines and Energy (MME) prepared a National Policy, Strategy, and Action Plan on Energy Efficiency in 2017.15ADB, Energy Sector Assessment, 2018. The Plan set a target to reduce national energy consumption by 20% compared to business-as-usual projections and to reduce national CO2 emissions to 3 million tons annually by 2035.16ADB, Energy Sector Assessment, 2018. These targets are still on the books, but there are questions about how Cambodia’s future energy buildout fits into this framework. The Cambodian utility company EDC has recently set solar targets as high as 1,815 MW (or 17% of peak demand) by 2030.17Keo Rattanak, “Current State of Cambodia’s Electricity Demand and Supply Outlook,” September 2020, accessed November 4, 2020, at https://drive.google.com/file/d/1T3P7HxSKvU1YRoNn9FhOUR1GDNIgkIzf/view. This indicates that alternative renewable energy technologies are penetrating the market, but the recent announcements of major new coal plants and purchases of coal power from Laos raise questions about future emissions. The international business community has raised concerns about these trends and called on the government to support further deployment of renewables.18Shaun Turton, “Cambodia’s shift to coal power riles global brands,” Nikkei Asia, August 11, 2020, accessed November 4, 2020, at https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Energy/Cambodia-s-shift-to-coal-power-riles-global-brands.

Electricity Transmission

The Mekong Infrastructure Tracker currently includes 48 transmission lines, of which 23 are operational, 20 planned, and 5 under construction. Operational transmission lines include 11 unique 115-kV and 12 unique 230-kV transmission lines. Remaining planned and under construction transmission line projects are similarly divided between 115 kV and 230 kV lines.

Prominent Project: Kampot Substation-Stung Hav Substation Transmission Line

| Project Name | Kampot Substaion-Stung Hav Substation |

| Subtype | Extra High Voltage |

| Current Status | Under Operational |

| Length (km) | 81.62km |

| Voltage (kV) | 230 kV |

| Year of Completion | 2013 |

| Lender/Financier | JICA, ADB |

| Lender/Financier Country | Japan; ADB |

| Country | Cambodia |

| Province/State | Kampot, Preah Sihanouk |

| Districts | Kampot, Tuek Chhou, Prey Nob, Stueng Hav |

| Main Basin | Cambodia Coastal Rivers Kampot Sihanoukvillle |

| Tributary | Coastal Rivers Kampot-Sihanoukville |

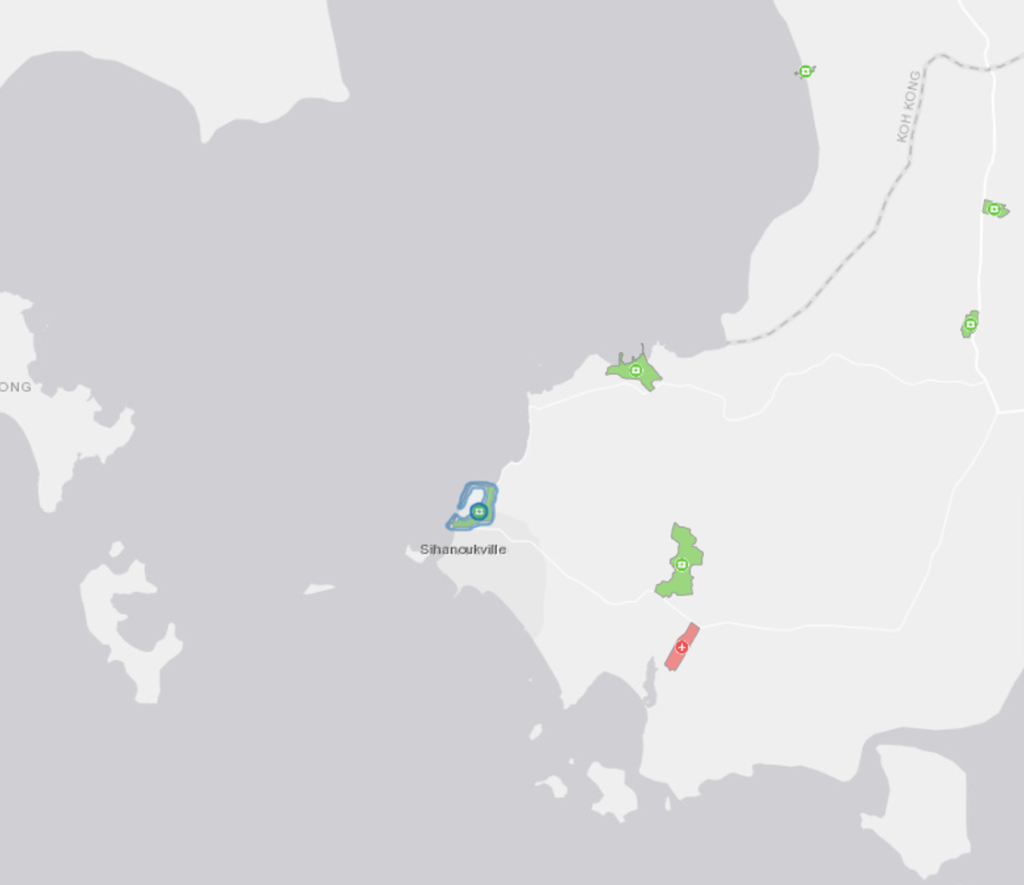

Development of the transmission line between Kampot Substation and Stung Hav Substation was planned in part to address Cambodia’s fragmented power sector. Prior to the completion of the transmission line in 2013, Sihanoukville relied on the isolated 14.5 MW diesel generator Sihanoukville Power Plant.19Asian Development Bank (ADB), Cambodia: Second Power Transmission and Distribution Project, accessed on September 17, 2021, at https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/project-document/183857/37041-013-pcr.pdf The growth and development of the city of Sihanoukville, upgrades to existing infrastructure, and the establishment of several Special Economic Zones necessitated expansion of the region’s electricity and distribution system. The completion of the transmission line between Kampot and Sihanoukville established the connection of the city to the national grid, thus meeting its growing electricity demand and fueling economic development in the region.

Prominent Project: Battambang 60 MW Solar

| Project Name | Battambang 60 MW Solar |

| Subtype | Solar |

| Current Status | Operational |

| Capacity (MW) | 60 MW |

| Year of Completion | 2020 |

| Country of Sponsor/Developer | China |

| Sponsor/Developer Company | Risen Energy |

| Country list of Construction/EPC | Germany, EU, France |

| Lender/Financier | Deutsche Investitions- und Entwichlungsgesellschaft, European Investment Bank, French Development Agency |

| Country | Cambodia |

| Province/State | Battambang |

| District | Sangkae |

| Watershed | Steng Mongkol Borei-Battambang |

| Latitude | 13.15862221 |

| Longitude | 102.9758937 |

The Battambang 60 MW Solar project is one of four solar power plants approved for construction in 2019 by the Royal Government in Cambodia and was recently connected to the national grid in early 2021. Like the other three solar projects, the Battambang 60 MW Solar power plant is part of a national plan to incorporate 450 MW of solar power into the national grid as noted by the country’s electricity supplier, Electricite du Cambodge (EdC) by 2022.20Thou Vireak, “60MW solar station in Battambang hooked to grid,” Phnom Pent Post, March 23, 2021, accessed September 27, 2021, at https://www.phnompenhpost.com/business/60mw-solar-station-battambang-hooked-grid The four new solar power plants are expected to begin power generation by the end of 2021 and will increase the country’s solar power generation capacity by 190 MW, a 120% increase in solar power generation currently linked to the national grid.

Cambodia’s economic growth over the last decade has been driven by tourism, manufacturing (primarily garments for export), and more recently commercial and residential construction. These three industries account for 70% of Cambodia’s economic growth and nearly 40% of the labor market.21The World Bank, Cambodia Economic Update, page 3. Agriculture is key for national food security and employmentand has been relatively resilient and actually increased its relative share of GDP during the COVD-19 pandemic.[i] There is substantial opportunity to diversify crop production away from rice to higher value added products and increase productivity through modernization.22The World Bank, Cambodia Economic Update, page 11. All four of these sectors rely on transportation for the effective flow to export goods and products, provide tourism services, and deliver necessary materials.23Asian Development Bank (ADB), Cambodia Transport Sector Assessment, Strategy, and Roadmap, September 2019. The World Bank 2018 Logistics Performance Index ranked Cambodia 98th out of 16024The World Bank, “World Bank Open Data,” The World Bank, retrieved on 22 October 2020. https://data.worldbank.org/.

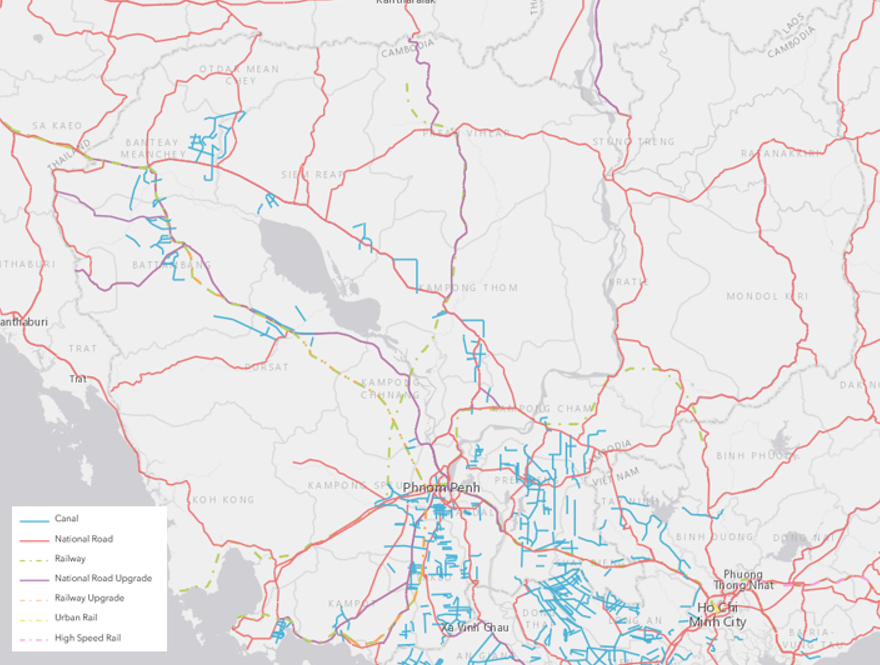

Cambodia’s location between Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam makes it a central and critical part of the Greater Mekong Subregion’s Southern Economic Corridor. The Southern Economic Corridor aims to connect key provinces in southern and eastern Thailand to coastal regions in Vietnam via Cambodia and southern Laos.25The Asian Development Bank, Strategy and Action Plan for the Greater Mekong Subregion Southern Economic Corridor, 2010, page 5, accessible at https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/28006/gms-action-plan-south.pdf. A major road and rail route is being developed and expanded over portions of existing routes to connect Bangkok to Ho Chi Minh City via Phnom Penh, but more investment is needed to complete critical segments of these projects.

The Mekong Infrastructure Tracker includes project-level data on 5,572 km of national roads, 2,117 km of national road upgrades, 908 km of railways, 607 km of railway upgrades, and 3,353 km of canals currently in operation.

Road Transport

Road transport accounts for over 90% of freight and passenger transport in Cambodia, making it by far the largest method of transportation.26Asian Development Bank (ADB), Cambodia Transport Sector Assessment, 2019. The government of Cambodia has consistently identified roads as one of four key priority areas for development, and this has continued under the Sixth Legislature of the National Assembly in 2018 with a focus on improving logistics and connectivity.27Royal Government of Cambodia, Rectangular Strategy for Growth, Employment, Equity, and Efficiency: Building the Foundation Toward Realizing the Cambodia Vision 2050, Phnom Penh, September 2018, page 10, at http://cnv.org.kh/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Rectangular-Strategy-Phase-IV-of-the-Royal-Government-of-Cambodia-of-the-Sixth-Legislature-of-the-National-Assembly-2018-2023.pdf. The prioritization of road infrastructure has paid off, as Cambodia’s Logistics Performance Index ranking rose rapidly from 129 in 2010 to 98 in 2018.

To further improve connectivity and transportation efficiency, Cambodia will need to upgrade and expand its high-quality road network. Cambodia has over 61,000 km of domestic roads, but the vast majority are rural roads and only approximately 6,200 km of the national and provincial roads are paved.28ADB, Cambodia Transport Sector Assessment, 2019, page 4. Improving the quality of these roads—in particular, paving more of the provincial and national roads—will help improve the system’s overall effectiveness.

The Mekong Infrastructure Tracker has project-level detail on 5,572 km of operational national roads and 2,117 operational upgrades to national roads. Users can view provincial and local roads on the base map layer.

Railway Transport

Rail currently plays a minimal role in terms of passenger transportation inside Cambodia, due in part to its limited level of development. Cambodia only has two operational railway lines: the Southern Line, built in the 1960s, and the Northern Line which was constructed during the French colonial period in the 1930s.29Cambodia Ministry of Public Works and Transport, “Railway Services,” accessed November 3, 2020, at https://www.mpwt.gov.kh/en/public-services/railway-services. The Northern line links Phnom Penh to Sisophon and Poi Pet along the Thai-Cambodia border, while the Southern Line links Phnom Penh to the coastal port at Sihanoukville.30JICA, page 2-78, at https://openjicareport.jica.go.jp/pdf/12284980_01.pdf.

Much of Cambodia’s railway system was damaged during the civil war, but the government of Cambodia embarked on major efforts to rehabilitate the railway in the late 2000s. With support from the Asian Development Bank, the railway was turned from a state-owned enterprise into a public-private-partnership project.31ADB, Cambodia Transport Sector Assessment, 2019.

In 2011 Cambodia’s Ministry of Public Works and Transportation and the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) agreed to formulate a national master plan for the railway network.32Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), The Data Collection Survey on International Logistics Function Strengthening in the Kingdom of Cambodia, June 2016, page 2-80, accessed at https://openjicareport.jica.go.jp/pdf/12284980_01.pdf Published in 2014, the Railway Master Plan identified a series of priority projects to expand the rail network and improve access to east and northeastern Cambodia as well as create eight branch lines to link in other provinces.33JICA, page 2-81. Through 2020 KOICA recommended prioritizing improvements to the existing Northern Line and creation of a third main rail line that would link Phnom Penh to the eastern provinces and the border with Vietnam.34Hort Sroeu, “Infrastructure Development in Cambodia,” Korea International Cooperation Agency Cambodia, presentation on January 27, 2017, accessed at https://www.slideshare.net/HortSroeu/final-draft-infrastructure-development-in-cambodia-85232687.

Plans for many of these proposed projects are still relatively early in the development stage. The Mekong Infrastructure Tracker showcases over 1,515 km worth of operational railways and railway upgrades with an additional 1,362 km of rail under development.

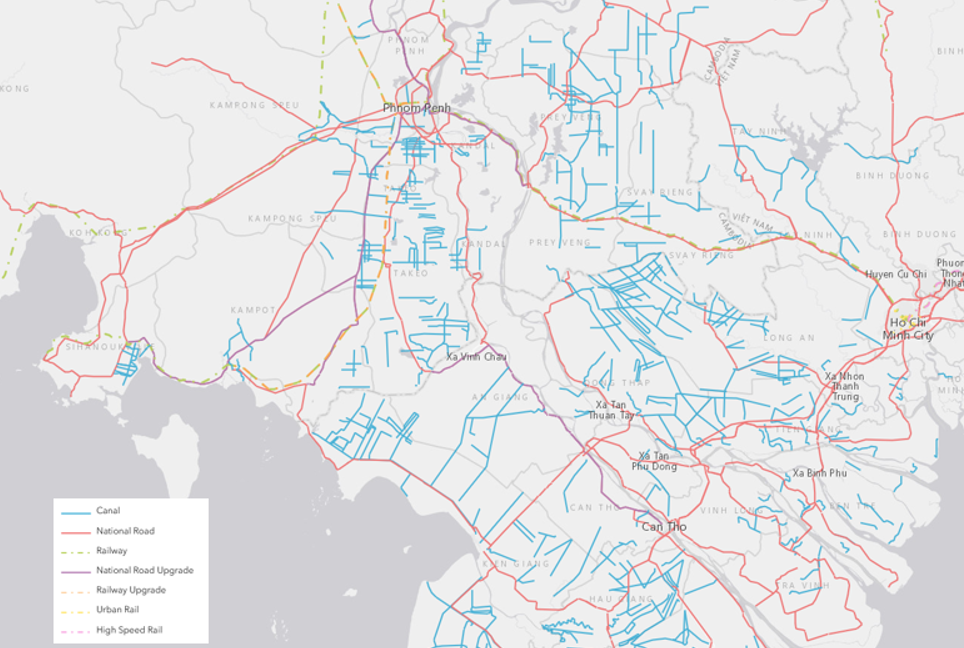

Cambodia’s Ministry of Public Works and Vietnam’s Ministry of Transport announced a proposal for the 281km Phnom Penh-Ho Chi Minh railway plan in early 2018. The railway would cross the border at Bavet city in Cambodia’s Svay Rieng province, entering the town of Moc Bai on the Vietnamese side. Bavet, a small city with a population of just under 40,000, is one of the poorest in the country, its main income source being Vietnamese patronage of its 12 casinos.35Global Construction Review, “Cambodia Mulls Railway to Vietnam”, Global Construction Review, 7 October 2020, retrieved on 4 November 2020 at https://www.globalconstructionreview.com/news/cambodia-mulls-railway-vietnam/ The railway could potentially position Bavet as an “international border gateway”, facilitating the trade of manufactured goods produced in the nearby Svay Rieng special economic zone.36Global Construction Review, 2020 It may also increase Cambodian access to Chinese markets, as an estimated 40% of Chinese goods bound for Cambodia travel through Vietnam.37Global Construction Review, 2020 While attracting and securing investment is still an ongoing process and the project is in early stages of development, if built, the railway would significantly boost connectivity in the Mekong River Delta region.

Waterways

The Mekong River system in Cambodia contains a vast network of connected rivers, tributaries, and canals totaling 11,000 km altogether.38Brian Eyler and Courtney Weatherby, “Letters from the Mekong: Toward a Sustainable Water-Energy-Food Future in Cambodia,” The Stimson Center, 2020, page 3 While not all of this is navigable, waterway transportation plays a vital role in the national economy and in terms of trade and cargo. The Mekong River plays a major role in North to South connectivity, with significant traffic and commerce between Phnom Penh and the Mekong Delta in Vietnam.

In December 2009, Cambodia and Vietnam signed a bilateral Treaty on Waterway Transportation that established freedom of navigation between the two countries, improve river access and efficiency along the 65 river ports.39Mekong River Commission, “Cambodia and Viet Nam formally open-up cross-border river trade on the Mekong,” December 17, 2009, accessed November 3, 2020, at http://www.mrcmekong.org/news-and-events/news/cambodia-and-viet-nam-formally-open-up-cross-border-river-trade-on-the-mekong/. This caused rapid growth in business at the Phnom Penh Autonomous Port: goods processed rose 45% in 2010,40Chun Sophal, “Port on track to surpass 2010 traffic goal,” The Phnom Penh Post, December 6, 2010, accessed November 3, 2020, at https://www.phnompenhpost.com/business/port-track-surpass-2010-traffic-goal. and as a result in 2011 Cambodia began construction of new container docks to expand storage capacity.41Council for the Development of Cambodia, “Inland Water Transportation,” Invest Cambodia, accessed November 3, 2020, at http://www.cambodiainvestment.gov.kh/investors-information/infrastructure/inland-water-transportation.html. Connectivity to Laos remains limited due to natural rapids just 2 km north of the Lao-Cambodia border.

The Mekong Infrastructure Tracker includes detailed data on 247 canals that amount to 3,352 km in total length, located mostly in provinces surrounding the Tonlé Sap lake and the lowlands surrounding the Mekong River south of Phnom Penh.

Industrial Zones and Transportation Hubs

Industrialization and export-oriented manufacturing have played a key role in driving Cambodia’s transition to lower middle-income status; industry has sharply risen to make up 34% of GDP as of 2019, according to the World Bank.42The World Bank, “World Bank Open Data,” The World Bank, retrieved on 22 October 2020. https://data.worldbank.org/ Over 25% of the labor force is employed in industry, with most households participating in garment production, construction and general manufacturing.43International Labour Organization, “Country Profiles”, The International Labour Organization, retrieved on 23 October 2020 https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/country-profiles/ The Mekong Infrastructure Tracker dataset provides details on more than 9 airports, 2 railway stations, 1 sea or inland ports, and 25 special economic zones and other industrial zones of importance in Cambodia.

Special Economic Zones

To facilitate industrialization, Cambodia has chosen a development model of promoting special economic zones open to foreign investors. Currently, Cambodia has 25 special economic zones totaling more than 75 square kilometers with cluster area near the Thai border in the northwest, near the Vietnamese border in Svay Rieng Province, in Sihanoukville and in Phnom Penh. The Mekong Infrastructure Tracker reveals that foreign investment in these SEZs comes mainly from China and Taiwan.

Air Transport

Air transit in Cambodia has a low share of national transportation and plays an insignificant role in terms of freight traffic.44ADB, Cambodia Transport Sector Assessment, 2019. However, it is absolutely key for tourism: of the 6.2 million tourists in 2018, two-thirds came via airplane into one of Cambodia’s three international airports.45Cambodia Ministry of Tourism, Tourism Statistics Report: Year 2018, page 3, at https://amchamcambodia.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Year_2018.pdf. Tourism has grown rapidly in recent years and in 2019 Cambodia saw a year-on-year increase of 11%, the third highest growth in all of ASEAN.46Chea Vannak, “Cambodia 3rd in ASEAN for tourist growth,” The Khmer Times, January 22, 2019, accessed November 4, 2020, at https://www.khmertimeskh.com/570963/cambodia-3rd-in-asean-for-tourist-growth/. While the coronavirus pandemic in 2020 has deeply disrupted tourism, tourism numbers in 2018 had almost reached the 2020 target of 7 million tourists in Cambodia’s Tourism Development Strategic Plan.47ADB, Cambodia Transport Sector Assessment, 2019.

Cambodia has eight airports and project-level details are available for eight of them in the Mekong Infrastructure Tracker. There is a need to upgrade existing airport infrastructure in order to meet the rapidly rising demand. Phnom Penh International Airport and Siem Reap International Airport can each respectively handle about 5 million passengers a year.48ADB, Cambodia Transport Sector Assessment, 2019. The likelihood that growth in tourism will outpace these numbers has prompted plans for expansion.

Between 2013 and 2018, approximately $2.9 billion was committed to upgrades and new construction in the aviation sector.49ADB, Cambodia Transport Sector Assessment, 2019. Much of this is for the development of new airports, including a new and upgraded Phnom Penh International Airport which will cost $1.5 billion.50Sok Chan, “Capital’s new airport construction largely unaffected by days of deluges,” The Khmer Times, October 20, 2020, accessed November 4, 2020, at https://www.khmertimeskh.com/50774849/capitals-new-airport-construction-largely-unaffected-by-days-of-deluges/. The New Siem Reap International Airport began construction in early 2020 and should begin operation in 2023.51Sorn Sarath, “$880m Siem Reap International Airport to be ready in 3 years,” The Khmer Times, May 13, 2020, accessed November 4, 2020, at https://www.khmertimeskh.com/722558/880m-siem-reap-international-airport-to-be-ready-in-3-years/. The third major project is the Dara-Sakor International Airport in Koh Kong Province, which is expected to start operation in mid-2021.52Sok Chan, “Luxury new international airport ‘to be operational by mid-2021,’” The Khmer Times, October 15, 2020, accessed November 4, 2020, at https://www.khmertimeskh.com/50773320/luxury-new-international-airport-to-be-operational-by-mid-2021/. The developer of the Dara-Sakor International Airport was sanctioned under the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act by the US Treasury over land seizures associated with the project.53U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Sanctions Chinese Entity in Cambodia under Global Magnitsky Authority,” September 15, 2020, accessed November 4, 2020, at https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm1121.

Port Infrastructure

Cambodia has two main ports: the Phnom Penh Autonomous Port, which is an inland river port near the confluence of the Tonle Sap and Mekong rivers, and the Sihanoukville Autonomous Port (SAP), which is Cambodia’s only existing deep-water port. Both are financially independent state-owned enterprises and they hold the majority of the import-export volume (12.9 million tons at PPAP and 5.2 million tons through SAP in 2018).54ADB, Cambodia Transport Sector Assessment, 2019, page 13. There are also many smaller ports along the Mekong, Bassac, and Tonle Sap Rivers that supply local communities. Three smaller maritime ports in Koh Kong Province—Okhna Mong, Sre Ambel, and Koh Kong—are used primarily for importing goods from Thailand.55ADB, Cambodia Transport Sector Assessment, 2019, page 13.

The government does have plans to expand port infrastructure. Priority activities include developing technical standards for further port development and operation; rehabilitate existing waterways, ports, and related infrastructure; improve classification of vessels and waterway depths to improve navigation; and dredge waterways to improve access for larger vessels along inland waterways.56Mr. Huon Rath, The Waterways Infrastructure Development in Cambodia, Ministry of Public Works and Transport, presentation at PIANC, October 24, 2019, accessed November 4, 2020, at https://www.pianc.org/uploads/files/EVENTS/1st-PIANC-CAMBODIA-SEMINAR/06-Mr.-Huon-Rath-PIANC-Seminar-24-25-Oct-2019.pdf.

Prominent Industrial Zone Snapshot: Sihanoukville Port Special Economic Zone

| Project Development Cycle Stage | Operational |

| Total Investment (million USD) | 34 |

| Area (km2) | 2.146707 |

| Sponsor/Developer: | PAS & JBIC Loan CP-P6 |

| Country | Cambodia |

| State or Province | Krong Preah Sihanouk |

| District | Mittakpheap |

| Main River Basin | Cambodia Coastal Rivers Kampot Sihanoukville |

| Tributary | Coastal Rivers Kampot-Sihanoukville |

| Latitude | 10.6519349885541 |

| Longitude | 103.515604169144 |

| Data Source | Open Development Cambodia |

Sihanoukville Port SEZ is connected to one of the two main maritime ports in Cambodia. Established in 2009, this SEZ supports businesses in the vicinity of the port and was developed by the Port Authority of Sihanoukville and was supported with loans from the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC). Unlike most of the other SEZs in Cambodia, the Sihanoukville Port SEZ is a public-private joint venture.57Peter Warr and Jayant Menon, Cambodia’s Special Economic Zones, ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 459, October 2015, page 7, at https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/175236/ewp-459.pdf. Investors in the zone are able to receive benefits in terms of 50-year land leases, exemption of import and export duties, no value added tax, and exemptions from taxes on profit for 9 years.58Port Authority of Sihanoukville, “Sihanoukville Port Special Economic Zone,” accessed November 4, 2020, at http://www.pas.gov.kh/en/page/sihanoukville-port-special-economic-zone-spsez.

Reservoirs

Similar to its regional neighbors in the Greater Mekong Subregion, Cambodia’s reservoirs store water for irrigation, electricity production, and general water supply. The various uses of these reservoirs fall within the purview of a wide range of relevant ministries and departments. Overall, the Ministry of Water Resources and Meteorology is the leading water sector agency and is responsible for the management and conversation of water as mandated in the 2007 Water Law.59Mak Sithirith, “Water Governance in Cambodia: From Centralized Water Governance to Farmer Water User Community,” Resources, August 31, 2017, accessed September 20, 2021, at https://www.mdpi.com/2079-9276/6/3/44/pdf

The Mekong Infrastructure Tracker currently has details on 80 reservoirs in Cambodia, of which 75 are used for hydropower production and 5 for water supply. Only 15 of these are operational and have reservoir shapes associated; the remaining 65 projects are planned and are denoted by location of the proposed project.

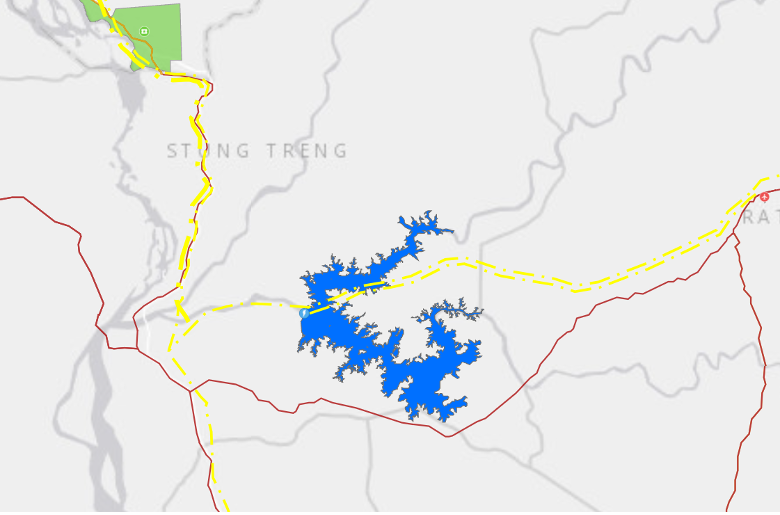

Prominent Reservoirs Snapshot: Lower Sesan 2

| Project Name | Lower Sesan 2 |

| Subtype | Hydropower |

| Project Status | Operational |

| Year of Completion | 2018 |

| Sponsor/Developer | Hydrolancang International Energy. Co, Royal Group, EVN |

| Country list of Sponsor/Developer | China, Cambodia, Vietnam |

| Financier/Lender | China EXIM Bank |

| Country list of Financier/Lender | China |

| Construction Company/EPC Participant | Hydrolancang International Energy Co. |

| Country list of Construction Company | China |

| Dam Height (m) | 75 |

| Water Level (masl) | 75 |

| Catchment Area (km²) | 49,200 |

| Surface Area (km²) | 1,471 |

| Reservoir Volume (km³) | 2.715 |

| Surface Area (km²) | 1,310 |

| Province | Stung Treng |

| District | Sesan |

| Watershed | Mekong-Lancang |

| Tributary | Sesan |

The reservoir of the Lower Sesan 2 hydropower dam is the largest in Cambodia with an estimated reservoir volume at 2.715 km³ and surface area at 1,471 km².60Hydro Power Lower Sesan 2 Co. Ltd., “Project profile,” accessed September 28, 2021, at http://www.hydrosesan2.com/project.php The dam is a key infrastructure project under China’s Belt and Road Initiative and is expected to generate about one-sixth of Cambodia’s total power generation- an important achievement in a country whose electricity demand is rapidly increasing to match its economic development. However, the development of the Lower Sesan 2 was not without controversy. The reservoir is located at an important river confluence between the Sesan and Srepok Rivers just above the Mekong River where local communities relied on fishing, agriculture, and non-timber forest products for their livelihoods and subsistence.61John Sifton, “Underwater: Human Rights Impacts of a China Belt and Road Project in Cambodia,” accessed September 28, 2021, at https://www.hrw.org/report/2021/08/10/underwater/human-rights-impacts-china-belt-and-road-project-cambodia# The construction phase and reservoir impoundment resulted in deforestation of approximately 34,000 hectares and the relocation of 2,700 households from riparian communities.62Sangeetha Amarthalingam and Say Tola, “Cambodians struggles to retain their identity after being displaced by dam,” accessed September 28, 2021, at https://www.thethirdpole.net/en/energy/cambodians-struggle-after-being-displaced-by-lower-sesan-2/