Recommendation:

Establish standing and reserve capacities to meet UN needs for rapidly deployable civilian specialist skills in conflict prevention and peacebuilding efforts worldwide. Such a new civilian capability, with an emphasis on gender parity, could be central to the early efficacy of future integrated UN peace operations and special political missions.

Global Challenge Update:

Violent conflicts are never static. Rapid emergency response post-conflict—and similarly energetic efforts to prevent new or recurrent conflicts—can reduce prospects of violence and increase chances for sustainable peace.1United Nations. General Assembly. Security Council. Report of the Secretary-General on peacebuilding in the immediate aftermath of conflict. A/63/881-S/2009/304. June 11, 2009, 1. https://www.un.org/ruleoflaw/files/pbf_090611_sg.pdf. But, in many instances, the international community’s capacity to quickly mobilize critical technical expertise for effective early action has proven to be less than satisfactory. The COVID-19 pandemic has further tested global institutional capacity to coordinate quick and effective responses to crises. The global outbreak has the potential to erode international crisis management systems and further destabilize fragile countries by exacerbating both domestic and regional tensions.2International Crisis Group. COVID-19 and Conflict: Seven Trends to Watch. Special Briefing No. 4. March 24, 2020. Accessed May 20, 2020. https://www.crisisgroup.org/global/sb4-covid-19-and-conflict-seven-trends-watch.

Building and sustaining peace require greater international civilian capacity to support the objectives of post-conflict reconstruction and governance.3Commission on Global Security, Justice & Governance (Albright-Gambari Commission). Confronting the Crisis of Global Governance. The Hague and Washington, D.C.: The Hague Institute for Global Justice and Stimson Center, 2015, 37. As the risk of conflict relapse in the early years of peace are high, the UN needs to quickly provide specialized civilian capacities that can effectively strengthen and support national peacebuilding efforts. Despite this urgent identified need to complement and strengthen national and local-level governing functions in fragile and conflict-affected situations, the UN faces significant challenges in deploying civilian capabilities to missions and settings with mandates that vary widely.4Dijkstra, H., Petrov, P., & Mahr, E. “Learning to deploy civilian capabilities: How the United Nations, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe and European Union have changed their crisis management institutions.” Cooperation and Conflict, 54 no. 4 (2019): 532. Accessed May 20, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010836718823814. Advancing Secretary-General António Guterres’ renewed focus on prevention requires a nimble global approach to identifying, sharing, and rapidly deploying civilian expertise to prevent and de-escalate violent conflict. The quality, speed, and effectiveness of its pool of civilian expertise needs to be improved, starting by diversifying and broadening it.5United Nations. General Assembly. Security Council. Report of the Secretary-General on Civilian capacity in the immediate aftermath of conflict. A/66/311–S/2011/527, para. 7. August 19, 2011.

Matching growing demand for civilian expertise with supply in an innovative, systematic way was the goal of the UN’s Civilian Capacity initiative (CIVCAP, 2009–14) and “CAPMATCH”—the UN’s former online civilian capacity sourcing platform. CAPMATCH was used, for instance, to provide country-level support to institution-building efforts in Liberia and Côte D’Ivoire.6United Nations. Peacebuilding Commission. Informal meeting of the Organizational Committee. Chairperson’s Summary of the Discussion. March 8, 2013, 2. Accessed May 20, 2020. https://www.un.org/peacebuilding/sites/www.un.org.peacebuilding/files/documents/chairs_summary-informal_oc_meeting_-8_mar_2013.pdf. Despite CIVCAP’s disbandment and the closure of the CAPMATCH platform, the initiative drew attention on the need for the UN to expand partnerships to support national institution-building after conflict, including by enhancing South-South and triangular cooperation, and partnerships with international financial institutions and regional organizations.7United Nations. Secretary-General. Civilian capacity in the aftermath of conflict. Report of the Secretary-General. A/68/696-S/2014/5. January 6, 2014, 7.

Innovation Proposal:

Building on these efforts (CIVCAP and CAPMATCH), the Albright-Gambari Commission proposed a new UN Civilian Response Capability to meet three distinct goals: (a) improving support for post-conflict institution-building grounded in national ownership; (b) broadening and deepening the pool of civilian expertise for peacebuilding; and (c) enhancing regional, South-South, and triangular cooperation in building and sustaining peace.8Ibidem, 1. Such an initiative would include a rapidly deployable cadre of 500 international staff possessing technical and managerial skills, and fifty senior mediators and Special Envoys/Representatives of the Secretary-General with special attention paid to the recruitment of women mediators and mission leaders in line with UNSCR 1325 (2000) and the UN’s Gender Parity Strategy. Ideally, this group would be complemented by a two-thousand-strong standby component of highly skilled and periodically trained international civil servants drawn voluntarily from across the UN system—including the World Bank and International Monetary Fund—and beyond, to tap specialized skillsets (including judges, municipal-level administrators, engineers, and technical specialists—particularly those with newly needed skills in areas such as cybersecurity).9Ponzio, Richard, Joris Larik et al. An Innovation Agenda for UN75. The Albright-Gambari Commission Report and the Road to 2020. Washington, D.C.: The Stimson Center, 2019, 27.

The proposed Civilian Response Capability would ensure that the UN could better respond to the urgent needs of conflict prevention and recurrence worldwide. It should be coordinated with other similar initiatives led by, among others, the African Union, European Union, and Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe. It can draw lessons from the EU’s Civilian Capabilities Development Plan launched in November 2018, which aimed to make the Civilian Common Security and Defence Policy “more capable, more effective, flexible and responsive.”10European Council. Civilian Common Security and Defence Policy: EU strengthens its capacities to act. November 19, 2018. Accessed May 20, 2020. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2018/11/19/civilian-common-security-and-defence-policy-eu-strengthens-its-capacities-to-act/, and European Council. Civilian CSDP Compact: Council adopts conclusions. December 9, 2019. Accessed May 20, 2020. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2019/12/09/civilian-csdp-compact-council-adopts-conclusions/. Investing in a system that provides immediate access to civilian leadership and expertise has the potential to reduce the outbreak and recurrence of violent conflict, thereby diminishing the need for costly, large-scale, and more politically intrusive interventions from the international community.11United Nations. Secretary-General, Civilian capacity in the aftermath of conflict, A/68/696-S/2014/5, 3.

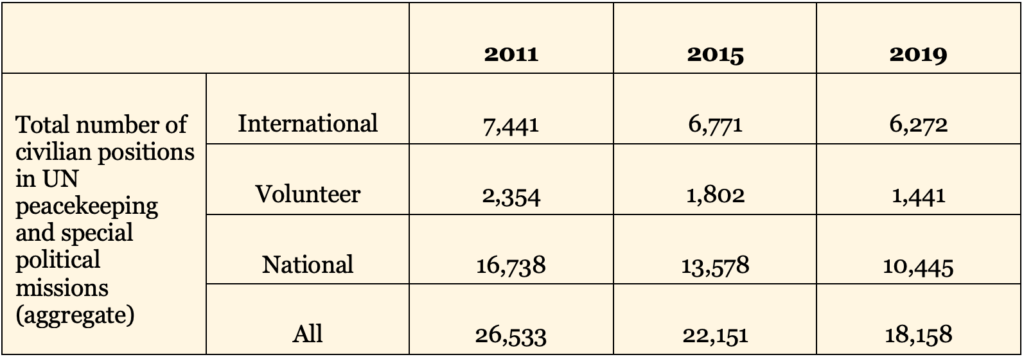

Civilian Positions in UN Peacekeeping and special political missions, 2011-19

Strategy for Reform on the Road to 2020 (UN75):

With thirty-seven UN-led political missions and thirteen peacekeeping operations that include thousands of civilian personnel worldwide, the UN’s need for technical expertise is ongoing and substantial (see table). The dramatic global economic slowdown poses great potential for unrest and renewed violence in fragile and conflict-affected states and regions. Non-state, illegal armed groups may use the health crisis and knock-on socioeconomic effects, including the growing specter of famine, to gain political and social influence. Directly addressing this heightened threat to vulnerable populations requires preventive action and experts who are readily available for deployment. A new UN Civilian Response Capability could not be timelier.

The present pandemic serves as a reminder that preparedness is essential to prevent and mitigate crises. In 2020, the UN’s 75th anniversary and the review of the UN Peacebuilding Architecture provide two complementary tracks where Member States, with support from the Secretary-General and external experts, can choose to invest in new standing and reserve capacities to meet rapid deployment needs for civilian specialist skills. Fortunately, the draft UN75 Declaration opens the door to consideration of such innovations.12United Nations. Declaration of the Commemoration of the Seventy-Fifth Anniversary of the United Nations. Draft, July 3, 2020, 3. Accessed July 3, 2020. https://www.un.org/pga/74/wp-content/uploads/sites/99/2020/07/UN75-FINAL-DRAFT-DECLARATION.pdf. If adopted by world leaders this September at the UN75 Summit, this commitment can pave the way for serious consideration of a new UN Civilian Response Capability and other innovative conflict prevention and response measures.

Notes

- 1United Nations. General Assembly. Security Council. Report of the Secretary-General on peacebuilding in the immediate aftermath of conflict. A/63/881-S/2009/304. June 11, 2009, 1. https://www.un.org/ruleoflaw/files/pbf_090611_sg.pdf.

- 2International Crisis Group. COVID-19 and Conflict: Seven Trends to Watch. Special Briefing No. 4. March 24, 2020. Accessed May 20, 2020. https://www.crisisgroup.org/global/sb4-covid-19-and-conflict-seven-trends-watch.

- 3Commission on Global Security, Justice & Governance (Albright-Gambari Commission). Confronting the Crisis of Global Governance. The Hague and Washington, D.C.: The Hague Institute for Global Justice and Stimson Center, 2015, 37.

- 4Dijkstra, H., Petrov, P., & Mahr, E. “Learning to deploy civilian capabilities: How the United Nations, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe and European Union have changed their crisis management institutions.” Cooperation and Conflict, 54 no. 4 (2019): 532. Accessed May 20, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010836718823814.

- 5United Nations. General Assembly. Security Council. Report of the Secretary-General on Civilian capacity in the immediate aftermath of conflict. A/66/311–S/2011/527, para. 7. August 19, 2011.

- 6United Nations. Peacebuilding Commission. Informal meeting of the Organizational Committee. Chairperson’s Summary of the Discussion. March 8, 2013, 2. Accessed May 20, 2020. https://www.un.org/peacebuilding/sites/www.un.org.peacebuilding/files/documents/chairs_summary-informal_oc_meeting_-8_mar_2013.pdf.

- 7United Nations. Secretary-General. Civilian capacity in the aftermath of conflict. Report of the Secretary-General. A/68/696-S/2014/5. January 6, 2014, 7.

- 8Ibidem, 1.

- 9Ponzio, Richard, Joris Larik et al. An Innovation Agenda for UN75. The Albright-Gambari Commission Report and the Road to 2020. Washington, D.C.: The Stimson Center, 2019, 27.

- 10European Council. Civilian Common Security and Defence Policy: EU strengthens its capacities to act. November 19, 2018. Accessed May 20, 2020. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2018/11/19/civilian-common-security-and-defence-policy-eu-strengthens-its-capacities-to-act/, and European Council. Civilian CSDP Compact: Council adopts conclusions. December 9, 2019. Accessed May 20, 2020. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2019/12/09/civilian-csdp-compact-council-adopts-conclusions/.

- 11United Nations. Secretary-General, Civilian capacity in the aftermath of conflict, A/68/696-S/2014/5, 3.

- 12United Nations. Declaration of the Commemoration of the Seventy-Fifth Anniversary of the United Nations. Draft, July 3, 2020, 3. Accessed July 3, 2020. https://www.un.org/pga/74/wp-content/uploads/sites/99/2020/07/UN75-FINAL-DRAFT-DECLARATION.pdf.