Executive Summary

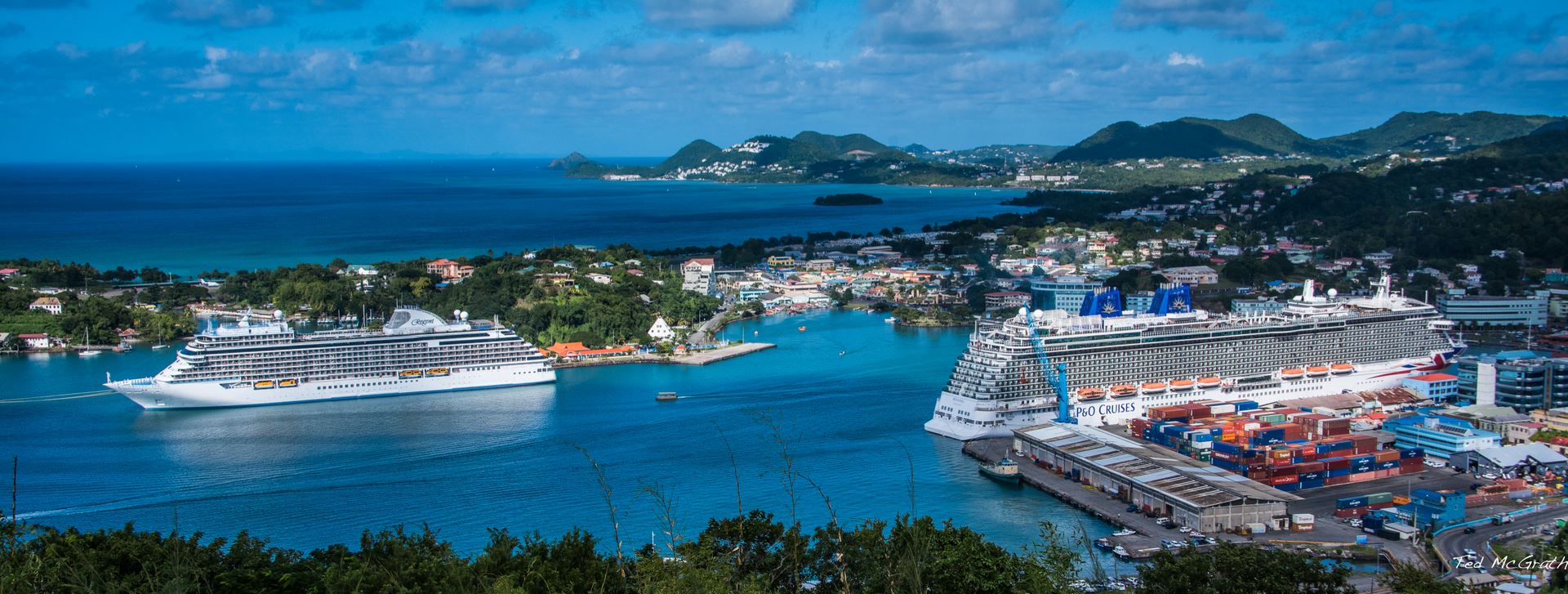

Built on reclaimed land and located on the west coast, Castries is the capital of Saint Lucia and its largest city. While the city population has remained relatively consistent, the urban area around Castries has expanded, extending from Grand Cul de Sac Bay in the South to Gros Islet in the north. This stretch of coastline is vulnerable to climate risks such as sea level rise and severe storms. Given the urban expansion, the geographic area of this risk profile was broadened to combine Gros Islet district and the city of Castries. The Castries-Gros Islet Corridor is home to nearly 50 percent of the nation’s population.

Saint Lucia is a leader among Caribbean states working to prioritize responses to climate change. Yet at the same time it suffers from climate and ocean risks. These include a high reliance on tourism to drive its economy, ecosystem degradation, and the vulnerability of key infrastructure to the physical impacts of storms and sea level rise. Furthermore, and partly as a consequence of its rapid urbanization, the study area continues to face issues relating to fresh and marine water quality.

With 1.2 million tourists arriving by cruise ship or plane in 2018, tourism continues to dominate the economy, contributing 41 percent to Saint Lucia’s GDP and employing 51 percent of the workforce. 1World Travel and Tourism Council, “Economic Impact 2018: St Lucia,” (London: WTTC, 2018), 3. While tourism is a vital part of the economy, it has unforeseen negative consequences. Unregulated tourist settlement construction and pollution from a lack of effective waste management has had secondary impacts on coastal ecosystems, such as coral reefs, and mangroves, and sea grass beds. Given the importance of tourism to the Castries-Gros Islet Corridor, an extreme weather event would be devastating, increasing the economic vulnerability in a city which already faces high urban unemployment. The city is already working to improve ecosystem resilience, flood management, and disaster planning, but more needs to be done.

The risk profile identifies three priority areas in need of action:

- Empower the city-level government to design and implement climate resilience plans

- Build a more sustainable tourist industry

- Improve urban infrastructure resilience

By advancing cross-cutting policies and channeling resources to these areas, Castries can lessen its vulnerability to climate and ocean risks.

Ecological Risk

Famed for its natural beauty, Saint Lucia’s marine and land ecosystems play a critical role in protecting coastal areas from flooding, supplying important fish sanctuaries, and helping Saint Lucia to stand out in a crowded global tourist market. However, ecosystem risk category scores are among the highest ecological risk category in the Castries risk profile, reflecting the growing physical risks posed by climate change and urbanization to the environment.

- In the Ecosystems category (expert weighted avg 6.18) the high scores in this category focus on the lack of coverage of coral reefs (8.03) and mangroves (7.88) which negatively impact marine habitats and nature-based city defenses. Data gaps excluded seven indicators from this category. 2Seven indicators in the Geology/Water category did not pass the data quality threshold. These Indicators are E3 Level of Coastal Sand Dune Coverage; E7 Health of existing Sand Dune systems; E9 Percent of GDP Protected by Mangroves; E10 Percent of GDP Protected by Coral Reefs; E11 Percent of GDP Protected by Coastal Sand Dunes; E12 Percent of GDP Protected by Sea Grass Beds; E13 Rate of Occurrence of Harmful Algal Blooms; E14Incidence of High Sargassum Abundance.

- In the Climate category (expert weighted avg 5.85) the high and medium-high scores in this category highlighted extreme heat events (8.27), droughts (7.08), floods (5.39), and hurricanes (5.17) as risks that increase the vulnerability of city residents. The risk of extreme weather is also reflected by a high-risk score in the number of people affected by extreme weather (8.11).

- In the Fisheries category (expert weighted avg 5.28), the medium-high risk scores in this category are fisheries management (7.23) and declining nearshore fish stocks (6.92), both of which pose a risk to food availability and the livelihoods of city residents.

- While the Geology/Water category (expert weighted avg 4.02) shows medium risk scores for sea-level rise (4.03) and coastal erosion (4.00), the category also highlights risks posed by poor freshwater quality (5.22).

Ecosystems across Saint Lucia, including coral reefs, mangrove forests, and sea grass beds, have degraded over time, affecting ecosystems services to the city. The clearance of mangrove forests in favor of construction projects has weakened the ability of Castries to combat storm surge. Recent regulations have reduced mangrove destruction, yet degradation continues, albeit on a smaller scale. Despite long-term coral degradation, recent positive stabilization trends have been seen, with 30 percent of national reefs now in “good condition,” as measured by the Reef Health Index. 3P.R. Kramer, L.M. Roth, S Constantine et al, “Saint Lucia’s Coral Reef Report Card 2016,” The Nature Conservancy, accessed October 2, 2019, https://caribnode.org/documents/87. However, declines in these marine ecosystems have already harmed nearshore fish stocks. Despite the high degree of fisheries management and compliance within the local fisheries sector, much of Castries’s fishing activities revolve around pelagic fish species which have the least regulations. 4Elizabeth Mohammed and Alasdair Lindop, “St. Lucia: Reconstructed Fisheries Catches, 1950-2010,” The Sea Around Us, The University of British Columbia: Fisheries Centre, 2015. Both issues are reflected in medium-high risk scores in the fisheries enforcement (7.23) and nearshore fisheries (6.92) indicators.

Despite the protection afforded by Castries’ location on the western side of the island, hurricanes still pose a direct threat. 5Caribbean Disaster Emergency Response Agency & World Bank, “Saint Lucia National Flood Plan: Floodplain Management and Flood Response (2003). In 2010, Hurricane Tomas hit Saint Lucia resulting in the death of 14 people and the displacement of thousands.6“Hurricane Kills 14 People in St Lucia,” BBC News, (November 2, 2010), accessed September 3, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-11672819. In 2013, much of Saint Lucia was damaged by an excessive rainfall event, termed the “Christmas Eve Trough Floods,” that caused severe flooding.7Carrie Gibson. “We Ignore the Disastrous Storms in the Caribbean at Our Peril.” The Guardian, (December 31, 2013), accessed November 23, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/dec/31/storms-caribbean-uk-climate-change. The deluge caused flash floods which damaged infrastructure and killed at least 15 people, especially in areas with high poverty levels.8“EU Agrees to Allocate EC$45M for St. Lucia and St. Vincent for 2013 Storm Flooding.” St. Lucia News Online, (September 26, 2014), accessed September 23, 2019, https://www.stlucianewsonline.com/eu-agrees-to-allocate-ec45m-for-st-lucia-and-st-vincent-for-2013-storm-flooding/. Hurricane Matthew’s heavy rainfall in 2016 led to flooding, power outages, and disruption of the fresh water supply in Castries.9“DREF Operations Final Report: Saint Lucia Hurricane Matthew,” International Federation of Red Cross and Red Cross Crescent Societies, July 20, 2017. These events are reflected in a high-risk score for people affected by extreme weather (8.11), with eight percent of the national population impacted by extreme weather events per year between 2003 to 2018.10Data taken from the EM-DAT The International Disaster Database available at: https://www.emdat.be/.

Drought is also a cause for concern across the study area. Castries depends upon precipitation for the majority of its water supply, and drought increases vulnerability, as seen in the 2009-10 drought which triggered a state of emergency and diminished agricultural output.11UNEP, “National Environmental Summary: Saint Lucia,” United Nations Environment Programme, Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean (2010). Moreover, watersheds in the study area are vulnerable to water contamination. Poor waste management and urban run-off are polluting the surface freshwater supplies upon which Castries’ relies.12UNFAO, “AQUASTAT Country Profile – Saint Lucia,” United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, 2015. In addition, expert interviews noted that informal housing construction also contributes to both marine and freshwater water pollution.13Interview with the Saint Lucia Water Resources Management Agency and the Saint Lucia Tourism Authority. Interviews took place in May 2019. Finally, extreme heat events present a challenge to Castries as they increase water scarcity and deter tourists, one of Castries’s main sources of economic security. Overall, while tourist arrivals have not diminished, studies show that tourists are becoming more aware of climate risks when choosing their vacation destination.14J Forster, P.W. Schuhmann, I.R. Lake. et al, “The Influence of Hurricane Risk on Tourist Destination Choice in the Caribbean Climatic Change 114 (2012): 745. This view was corroborated in expert interviews, which noted that the risk of extreme heat could reduce tourist numbers in Saint Lucia.15Interview with the Saint Lucia Chamber of Commerce. Interview took place in May 2019.

Financial Risk

The Castries-Gros Islet Corridor hosts a high concentration of roads, settlements, and the majority of the island’s population and critical infrastructure. This concentration of economic activity on low-lying coastal land, along with a reliance on tourism as its primary industry, represents two key areas of risk. One study estimated that without significant improvements in coastal resilience, Saint Lucia could lose up to $20 million annually by 2025 and $70 million by 2100, under a global high emissions scenario.16Ramón Bueno, Cornelia Herzfeld, Elizabeth A. Stanton, and Frank Ackerman, “The Caribbean and Climate Change: The Costs of Inaction” Stockholm Environment Institute—US Center & Global Development and Environment Institute, Tufts University (2008). Another study estimated that one meter of sea level rise could flood 30 percent of tourism properties.17Merkevia Isaac, “The Implications of Sea-level Rise for Tourism in St. Lucia,” UWSpace (2013), https://hdl.handle.net/10012/7637.

- In the Economics category (expert weighted avg 7.20), high scores in the indicators which measure the vulnerability of people to climate shocks: national youth unemployment (8.40), national unemployment rate (8.05), income inequality (7.95), and dependence on the informal economy (7.52) increase the economic insecurity of city residents to climate change.

- The Infrastructure category (expert weighted avg 5.16) highlights a dependency on oil imports and a lack of renewable energy generation (7.17), which increases Castries reliance on oil tankers. Other public infrastructure including poor road networks (6.65), the geographic location of freshwater distribution facilities (6.42), and poor wastewater management (5.98) are also at risk from storms and sea level rise.

- While the Major Industries category (expert weighted avg 4.42) highlights medium risk scores in fishing (nearshore 3.73 and offshore 3.60) and agriculture sectors (2.80), it highlights the importance of tourism (5.52) to the overall economic security of Castries.

Since the erosion of European Union trade preferences in the 1990s, the economy of Saint Lucia has become increasingly dependent on tourism as the economy has shifted towards a more service dominated model of development.18UNFAO, “AQUASTAT Country Profile – Saint Lucia,” United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, 2015. Despite the success of the industry, driven by the “sun-sea-sand” model, unsustainable land use, climate change, and environmental degradation continue to threaten the success of the tourist industry.19Isavela Monioudi, “Climate Change Impacts on Coastal Transportation infrastructure in the Caribbean,” Enhancing the Adaptive Capacity of Small Island Developing States – Saint Lucia: A Case Study,” (Geneva: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2017), accessed November 23, 2019, https://sidsport-climateadapt.unctad.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Executive-summary-St-Lucia.pdf.

The construction of hotels and other tourism infrastructure – including restaurants, gift shops, and cruise ship facilities – in the study area have had a variety of environmental impacts. These include destruction of natural marine and estuarine habitats, loss of productive agricultural land, and soil erosion.20Bradley Walters, “St Lucia’s Tourism Landscapes: Economic Development and Environmental Change in the West Indies,” Caribbean Geography 21 (2016): 10. When interviewed, multiple experts stated that inappropriate land use and management is a central factor contributing to environmental degradation in the Castries-Gros Islet Corridor.21Interview with Saint Lucia Tourism Authority and the Saint Lucia Chamber of Commerce. Interviews took place in May 2019. The construction is placing greater stress on natural resources and biodiversity, and the capacity to produce food and retain freshwater has been diminished.22UNFAO, “AQUASTAT Country Profile – Saint Lucia,” United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, 2015. Moreover, increased water consumption by the tourism sector, when compounded by climate change, is increasing food and water insecurity throughout Saint Lucia, as well as suppressing long-term growth prospects.23Ibid.

Critical infrastructure networks in Saint Lucia are also exposed to coastal and inland flooding. Key economic infrastructure in the study area, including roads, airports, the seaport, fuel storage, and energy supply networks are located along the coast or on low-lying reclaimed coastal land. Disruption to this infrastructure would impact the whole island. Climate change will likely exacerbate the current impact of flooding. While growth in population, unplanned settlement construction, and tourism will likely compound this impact.24R Miller, et al, Climate Change Adaptation Planning in Latin American and Caribbean Cities Complete Report: Castries, Saint Lucia, 2012. There are further concerns that the energy infrastructure in Saint Lucia, and in Castries in particular, is exposed to the impacts from coastal and inland flooding, as well as high winds during tropical storms and hurricanes.25P.A. Murray and B. Tulsie, “Saint Lucia Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessment – Coastal Sector. Provided by the Ministry of Physical Development & the Environment, Government of Saint Lucia (2011).

Transportation infrastructure is also at risk, as evidenced by high and medium-high indicator scores in road, airport, and seaport resilience. Poor road quality and landslide risk can impede disaster response, particularly to poorer areas of the Castries-Gros Islet Corridor. George F.L. Charles Airport, which sits along the coast is prone to flooding from both precipitation and storm surge event, despite being situated 3.4 meters above sea level.26Ibid. However, the risk to the coastal city is negated by the fact that George F.L. Charles Airport is a secondary airport with most of the international traffic landing at Hewanorra International Airport, located in the southeast corner of the country. Nevertheless, because of the distance that tourists must travel over roads to get to Gros Islet, the tourism industry is still vulnerable due to poor road quality, which are at risk from floods and landslides.

Port Castries has been able to withstand past storm surges without sustained damage. However, during Hurricane Dean in 2007, large vessels were forced to return to open waters during the storm event to avoid floating debris that drained off the island into the harbor. Nevertheless, operations at George F.L. Charles Airport and at Port Castries have never fully been halted due to flooding.27Ibid. Finally, Saint Lucia relies on imported oil for the majority of its energy. This exacerbates the reliance on Cul-de-Sac Bay – where oil facilities are located – for its economic security. Despite its potential for wind and solar power, renewables make up a small proportion of overall energy generation, as reflected in the medium-high risk score of 7.17.28“Renewable Energy Sector Development Project (P161316).” Renewable Energy Sector Development Project (P161316). The World Bank, May 30, 2017. https://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/949751496156024515/pdf/ITM00184-P161316-05-30-2017-1496156021818.pdf.

Political Risk

Like many small island developing states in the Caribbean, Saint Lucia has a democratically elected government. In response to the threat posed by climate change, the government of Saint Lucia has spearheaded numerous climate-related development projects, including the implementation of the Special Programme on Adaptation to Climate Change, which has sought to strengthen critical coastal infrastructure in Castries. While relatively low CORVI risk scores across social/demographic, governance, and stability categories show that Saint Lucia has been successful in building political capacity to adapt to climate risks, the scores also highlight vulnerabilities which could be exacerbated by a changing climate.

- The Social/Demographics category (expert weighted avg 4.86) highlights population trends such as urbanization of the study area (6.20), population density (5.43), and a high dependency ratio (7.40) which increases the vulnerability of Castries to extreme weather events.

- The Stability category (expert weighted avg 4.81) shows a comparatively high number of people employed in artisanal fishing (5.37) and tourist (5.30) sectors.29One indicator in the Stability category did not pass the data quality threshold. This indicator is S3 Percent of People Employed in Port and Shipping Industries.

- The Governance category (expert weighted avg 4.55) shows medium risk scores in the rule of law (3.20) and civil society engagement (2.95) scores. However, unequal access to healthcare (6.42), a lack of trust in ethics enforcement bodies (5.75), and relatively low voter turnout (5.65) are scored at medium-high risk.

Vulnerable populations are most at risk from climate change. Poorer areas, which are concentrated in the south and southeast of the study area, tend to have higher urban density. This is coupled with informal housing construction using substandard materials, and are often located on steep hillsides.30R Miller, et al, Climate Change Adaptation Planning in Latin American and Caribbean Cities Complete Report: Castries, Saint Lucia, 2012: 55. Few households have home insurance, increasing their risk to climate shocks.31Saint Lucia Population & Housing Census 2010. In addition, the absence of effective city planning, along with ineffective enforcement of existing building policies is contributing to the expansion of unplanned and unsafe settlements. This growth is occurring in vulnerable areas such as steep hillsides, watersheds, flood plains, and is also driving deforestation.32UNFAO, “AQUASTAT Country Profile – Saint Lucia,” United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, 2015. With Saint Lucia’s high dependency ratio and relatively unequal access to health services, the island’s poorest citizens are increasingly vulnerable to extreme weather events.33Dependency ratio is defined as the ratio of dependents–people younger than 15 or older than 64–to the working-age population–those ages 15-64. https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/age-dependency-ratio-working-age-population In the aftermath of Hurricane Tomas, health coverage was negatively impacted by over $3 million worth of damage to the hospitals across Saint Lucia, including Castries.34PAHO, “Case Studies in Grenada and Saint Lucia, (November 28, 2014), accessed November 23, 2019, https://www.paho.org/disasters/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&category_slug=news-caribbean&alias=2362-case-studies-grenada-and-st-lucia-resilient-health-services&Itemid=1179&lang=en.

Disaster risk management is an area where Saint Lucia has developed a well-defined policy and legislative framework. The National Emergency Management Office has created and implemented strategies to mitigate the risk of hazards for public and private development.35R Miller, et al, Climate Change Adaptation Planning in Latin American and Caribbean Cities Complete Report: Castries, Saint Lucia, 2012: 65. However, as incapsulated in the high financial risk scores, these policies lack legal weight and expert interviews documented concern that the guidelines are not often followed or enforced.

Overall, the Government of Saint Lucia leads the island’s climate change adaptation and disaster risk management strategy. Critically, at the city-level there are no independent policy tools or implementation mechanisms for city led adaptation to climate change. The Castries City Council, the only functioning city level governmental entity, has a limited mandate and resources to undertake such tasks.36Ibid, ii. Castries City Council also has limited responsibility for post-disaster recovery, and does not play a key role in disaster risk reduction or climate change adaptation planning. In response, the national government, through the National Integrated Planning and Programme Unit, has enacted Castries Vision 2030 in collaboration with UN Office for Project Services and the Office of the Mayor of Castries. This new initiative has the potential to improve climate resilience planning, but at this stage it is too early to gauge the extent to which climate change will be incorporated into its strategy for Castries and the greater Castries-Gros Islet Corridor.

Recommended Action Areas

Castries faces many climate and ocean risks that will potentially have an impact on the local population and economy. Physical hazard indicators such as heatwaves (8.27), droughts (7.08), floods (5.39), and hurricanes (5.17), when overlaid with the two highest scoring categories, economics (7.20) and ecosystems (6.18), have the potential to overwhelm current adaptation strategies. Many of the vulnerabilities and potential solutions are encompassed in a broad shift towards a blue and green economy, whereby the value of ecosystem services is integrated into urban planning. These high scoring categories and indicators highlight the need for the following priority actions.

Improved City Planning

Multiple stressors identified through indicators scores in mangrove coverage (7.88) and freshwater quality (5.22), measure the consequences of urban coastal development (6.45), especially in the tourist sector. Despite the need for improved city planning, as with many small island states, adaptation planning in Saint Lucia is generally undertaken at the national level. Enhancing the risk management and planning capabilities of the Castries Constituency Council, or establishing new city level agencies to address adaptation and planning, is crucial for promoting local level adaptive capacity in the context of the city.37Ibid. In this regard, Castries Vision 2030 could be used as a launch point for advancing integrated urban spatial planning.

Erosion and flooding are two key areas that increase vulnerability, especially for the poorest residents of Castries. Urban planning and building regulations remain limited and largely unenforced. Even minor rainfall can lead to flooding in Castries. In response, Castries has partnered with the World Bank to create the Management of Slope Stability in Communities project, which has reduced landslides.38“Saint Lucia” Leaders in Reducing Landslide Risk,” World Bank (June 11, 2013), accessed November 1, 2019, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2013/06/11/saint-lucia-oecs-leader-reducing-landslide-risk. These efforts should be expanded. In the long-term, Castries needs stronger construction laws and greater enforcement, as well as increased funding and capacity building within the urban planning authorities so that accurate zoning maps and regulations can be crafted to reduce vulnerability.39R Miller, et al, Climate Change Adaptation Planning in Latin American and Caribbean Cities Complete Report: Castries, Saint Lucia, 2012: 65.

Diversify Economic Output and Ensure a Sustainable Tourism Industry

The rapid pace of climate change is increasing the financial costs to the tourism sector, highlighting the urgent need for Saint Lucia to diversify its economy. This can be done through public and private investment that promotes economic diversification across service and industrial sectors, including light manufacturing, agricultural crops, and finance.

Due to the construction of hotels and related infrastructure without strategic regional planning40R Miller, et al, Climate Change Adaptation Planning in Latin American and Caribbean Cities Complete Report: Castries, Saint Lucia, 2012: ii., the tourism sector has negatively impacted Castries’ capacity to build resilience against risks such as inland flooding, storm surge, and hurricanes. The Government has recently announced more hotel projects to create opportunities in both the tourism and construction sectors.41Government of Saint Lucia, “SLTB Announces Island wide Hotel Expansion,” Saint Lucia – Access Government, (June 12, 2017), accessed September 2, 2019, https://www.govt.lc/news/sltb-announces-islandwide-hotel-expansion. However, these programs must be balanced against the negative impacts of tourism, such as poor waste management and the destruction of ecosystems, as Saint Lucia’s natural beauty is a vital part of its attraction as a tourist destination. Ecosystem services provided by the coastal environment play a critical role in protecting coastal infrastructure from extreme weather events and maintaining marine ecosystems and their biodiversity.42Lauretta Burke, Suzie Greenhalgh, Daniel Prager, and Emily Cooper, “Coastal Capital – Economic Valuation of Coral Reefs in Tobago and St. Lucia,” The Economic Valuation of Coral Reefs in the Caribbean. World Resource Institute, 2018.

Finally, while unemployment has declined slightly, in part due to growth in the tourism sector, it continues to be a source of vulnerability for Castries.43IMF, “St. Lucia: Staff Concluding Statement of the 2019 Article IV Mission,” International Monetary Fund, (November 18, 2019), accessed December 2, 2019, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2019/11/18/mcs111819-st-lucia-staff-concluding-statement-of-the-2019-article-iv-mission. In response, the Government of Saint Lucia has sought to diversify employment opportunities outside of tourism, through increasing the viability of agricultural employment44Office of the Prime Minister, “Government Renews Commitment to Employment,” Saint Lucia – Access Government, (June 13, 2017), accessed November 20, 2019, https://www.govt.lc/news/government-renews-commitment-to-employment. and by implementing a National Apprenticeship Program.45Anicia Antoine, “National Apprenticeship Program Students Graduate,” Saint Lucia – Access Government, (October 3, 2019), November 3, 2019, https://www.govt.lc/news/national-apprenticeship-program-students-graduate. These efforts should be continued through expanded investment in skills training.

Climate Resilient Infrastructure

As infrastructure is located on the coast and subject to increasingly extreme weather events, it is critical that city infrastructure adapt to the changing climate. This includes the Castries waterfront, transportation, energy, and water infrastructure. However, the relative vulnerability of critical infrastructure depends on many factors, including building materials, design, maintenance, and past damage.46R Miller, et al, Climate Change Adaptation Planning in Latin American and Caribbean Cities Complete Report: Castries, Saint Lucia, 2012: 90.

Given its reliance on rainfall, the government of Saint Lucia has recognized freshwater as a vulnerable resource.47Government of Saint Lucia, “Saint Lucia’s Sectoral Adaptation Strategy and Action Plan for the Water Sector (Water SASAP) 2018- 2028, under the National Adaptation Planning Process,” Department of Sustainable Development, Ministry of Education, Innovation, Gender Relations and Sustainable Development and Department of Agriculture, Fisheries, Natural Resources and Cooperatives, Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Physical Planning, Natural Resources and Cooperatives, 2018. In response, the National Utilities Regulatory Commission (NURC) was formed in 2016 to better manage water resources. As part of the NURC, the Operations and Maintenance Management system was developed to protect and maintain Saint Lucia’s water supply, which has reduced its risk to climate change. These efforts need to be expanded, with an increased focus on adopting water conservation practices, including increasing water efficiency across industries, particularly in the tourism sector. Damage to roads impairs post-disaster response and stalls economic activity, particularly in the socially vulnerable areas of East and South Castries. Improving road resilience, especially in areas prone to slope instability and coastal flooding, should be prioritized. Finally, conducting a detailed vulnerability analysis of selected critical infrastructure would serve to identify which structures and systems are most vulnerable and arm decision makers with recommendations on how to build resilience into the system.

Empirical data sources were used to construct the 1-10 scales which is then used to weight expert surveys through the coherence check.

Appendix

CORVI Weighting

The final score for each category depends on how much each indicator contributes to the overall score. The weighting procedure incorporates three different elements: a minimum data threshold, data confidence, and indicator importance.

- Indicators must reach a minimum data threshold to be included in the final risk category score. To meet the criteria an indicator must have at least one of the following: empirical data source or at least 3 expert surveys. If an indicator does not meet this minimum criterion, it is excluded. However, it is important to note that these data gaps are still noted in the final report and expert interviews are used to describe risks where CORVI scores are not available. Highlighting these data gaps also acts as a signpost for future data collection.

- Indicators that contain more robust data are weighted more heavily. Robust data is measured by the quality of the empirical data source and by the number of expert surveys.

- Indicators are weighted within each risk category using subject matter expert responses. Survey respondents are asked to identify the two most important and the two least important indicators for understanding risk in each. These two criteria are combined into an overall weight for each indicator.

Data Sources

Empirical data sources used to construct the 1-10 risk scales.

| Category | Data Sources |

|---|---|

| Geology/Water | Individual Country Statistic Offices; Global Fatal Landslide Database; World Bank; UN Environment; |

| Climate | EM-DAT International Disaster Dataset; National Aeronautics and Space Administration; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; Pan American Health Organization |

| Ecosystems | Global Fatal Landslide Database; Ocean Health Index; Coral Reef Health Index; World Resources Institute |

| Social/Demographics | CIA World Factbook; Individual Country Statistic Offices; UN Population Division; World Bank |

| Economics | Individual Country Statistic Offices; International Labor Organization; UN Development Programme; World Bank |

| Major Industries | World Bank; Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism Statistics; World Travel and Tourism Council |

| Fisheries | Individual Country Statistic Offices; Ocean Health Index; Environmental Performance Index; UN Food and Agriculture Organization; Sea Around Us Dataset |

| Infrastructure | Environmental Performance Index; International Energy Agency; Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative; United Nations Human Settlements Programme; World Bank; World Health Organization |

| Governance | Corruption Perceptions Index (Transparency International); INFORM Index for Risk Management; International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance; Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative; Rule of Law Index (World Justice Project); World Bank |

| Stability | Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism; International Labor Organization; Sea Around Us Dataset; UN Food and Agriculture Organization; World Travel and Tourism Council |

List of Organizations which provided expert surveys

Expert surveys were submitted by individuals from these organizations. In addition, some organizations opted to complete surveys as an institution. 40 surveys were collected for the Castries assessment.

| Castries, Saint Lucia |

|---|

| The Central Statistical Office of Saint Lucia |

| George Mason University, Center for Ocean-Land-Atmosphere Studies |

| Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Physical Planning, Natural Resources and Cooperatives |

| Organization of East Caribbean States |

| Saint Lucia Air and Sea Port Authority |

| Saint Lucia Chamber of Commerce, Industry, and Agriculture |

| Saint Lucia Department for Sustainable Development |

| Saint Lucia Electricity Services Limited |

| Saint Lucia National Trust |

| Saint Lucia Tourism Authority |

| United Nations Office for Project Services |

| Saint Lucia Water Resources Management Agency |

Notes

- 1World Travel and Tourism Council, “Economic Impact 2018: St Lucia,” (London: WTTC, 2018), 3.

- 2Seven indicators in the Geology/Water category did not pass the data quality threshold. These Indicators are E3 Level of Coastal Sand Dune Coverage; E7 Health of existing Sand Dune systems; E9 Percent of GDP Protected by Mangroves; E10 Percent of GDP Protected by Coral Reefs; E11 Percent of GDP Protected by Coastal Sand Dunes; E12 Percent of GDP Protected by Sea Grass Beds; E13 Rate of Occurrence of Harmful Algal Blooms; E14Incidence of High Sargassum Abundance.

- 3P.R. Kramer, L.M. Roth, S Constantine et al, “Saint Lucia’s Coral Reef Report Card 2016,” The Nature Conservancy, accessed October 2, 2019, https://caribnode.org/documents/87.

- 4Elizabeth Mohammed and Alasdair Lindop, “St. Lucia: Reconstructed Fisheries Catches, 1950-2010,” The Sea Around Us, The University of British Columbia: Fisheries Centre, 2015.

- 5Caribbean Disaster Emergency Response Agency & World Bank, “Saint Lucia National Flood Plan: Floodplain Management and Flood Response (2003).

- 6“Hurricane Kills 14 People in St Lucia,” BBC News, (November 2, 2010), accessed September 3, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-11672819.

- 7Carrie Gibson. “We Ignore the Disastrous Storms in the Caribbean at Our Peril.” The Guardian, (December 31, 2013), accessed November 23, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/dec/31/storms-caribbean-uk-climate-change.

- 8“EU Agrees to Allocate EC$45M for St. Lucia and St. Vincent for 2013 Storm Flooding.” St. Lucia News Online, (September 26, 2014), accessed September 23, 2019, https://www.stlucianewsonline.com/eu-agrees-to-allocate-ec45m-for-st-lucia-and-st-vincent-for-2013-storm-flooding/.

- 9“DREF Operations Final Report: Saint Lucia Hurricane Matthew,” International Federation of Red Cross and Red Cross Crescent Societies, July 20, 2017.

- 10Data taken from the EM-DAT The International Disaster Database available at: https://www.emdat.be/.

- 11UNEP, “National Environmental Summary: Saint Lucia,” United Nations Environment Programme, Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean (2010).

- 12UNFAO, “AQUASTAT Country Profile – Saint Lucia,” United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, 2015.

- 13Interview with the Saint Lucia Water Resources Management Agency and the Saint Lucia Tourism Authority. Interviews took place in May 2019.

- 14J Forster, P.W. Schuhmann, I.R. Lake. et al, “The Influence of Hurricane Risk on Tourist Destination Choice in the Caribbean Climatic Change 114 (2012): 745.

- 15Interview with the Saint Lucia Chamber of Commerce. Interview took place in May 2019.

- 16Ramón Bueno, Cornelia Herzfeld, Elizabeth A. Stanton, and Frank Ackerman, “The Caribbean and Climate Change: The Costs of Inaction” Stockholm Environment Institute—US Center & Global Development and Environment Institute, Tufts University (2008).

- 17Merkevia Isaac, “The Implications of Sea-level Rise for Tourism in St. Lucia,” UWSpace (2013), https://hdl.handle.net/10012/7637.

- 18UNFAO, “AQUASTAT Country Profile – Saint Lucia,” United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, 2015.

- 19Isavela Monioudi, “Climate Change Impacts on Coastal Transportation infrastructure in the Caribbean,” Enhancing the Adaptive Capacity of Small Island Developing States – Saint Lucia: A Case Study,” (Geneva: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2017), accessed November 23, 2019, https://sidsport-climateadapt.unctad.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Executive-summary-St-Lucia.pdf.

- 20Bradley Walters, “St Lucia’s Tourism Landscapes: Economic Development and Environmental Change in the West Indies,” Caribbean Geography 21 (2016): 10.

- 21Interview with Saint Lucia Tourism Authority and the Saint Lucia Chamber of Commerce. Interviews took place in May 2019.

- 22UNFAO, “AQUASTAT Country Profile – Saint Lucia,” United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, 2015.

- 23Ibid.

- 24R Miller, et al, Climate Change Adaptation Planning in Latin American and Caribbean Cities Complete Report: Castries, Saint Lucia, 2012.

- 25P.A. Murray and B. Tulsie, “Saint Lucia Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessment – Coastal Sector. Provided by the Ministry of Physical Development & the Environment, Government of Saint Lucia (2011).

- 26Ibid.

- 27Ibid.

- 28“Renewable Energy Sector Development Project (P161316).” Renewable Energy Sector Development Project (P161316). The World Bank, May 30, 2017. https://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/949751496156024515/pdf/ITM00184-P161316-05-30-2017-1496156021818.pdf.

- 29One indicator in the Stability category did not pass the data quality threshold. This indicator is S3 Percent of People Employed in Port and Shipping Industries.

- 30R Miller, et al, Climate Change Adaptation Planning in Latin American and Caribbean Cities Complete Report: Castries, Saint Lucia, 2012: 55.

- 31Saint Lucia Population & Housing Census 2010.

- 32UNFAO, “AQUASTAT Country Profile – Saint Lucia,” United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, 2015.

- 33Dependency ratio is defined as the ratio of dependents–people younger than 15 or older than 64–to the working-age population–those ages 15-64. https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/age-dependency-ratio-working-age-population

- 34PAHO, “Case Studies in Grenada and Saint Lucia, (November 28, 2014), accessed November 23, 2019, https://www.paho.org/disasters/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&category_slug=news-caribbean&alias=2362-case-studies-grenada-and-st-lucia-resilient-health-services&Itemid=1179&lang=en.

- 35R Miller, et al, Climate Change Adaptation Planning in Latin American and Caribbean Cities Complete Report: Castries, Saint Lucia, 2012: 65.

- 36Ibid, ii.

- 37Ibid.

- 38“Saint Lucia” Leaders in Reducing Landslide Risk,” World Bank (June 11, 2013), accessed November 1, 2019, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2013/06/11/saint-lucia-oecs-leader-reducing-landslide-risk.

- 39R Miller, et al, Climate Change Adaptation Planning in Latin American and Caribbean Cities Complete Report: Castries, Saint Lucia, 2012: 65.

- 40R Miller, et al, Climate Change Adaptation Planning in Latin American and Caribbean Cities Complete Report: Castries, Saint Lucia, 2012: ii.

- 41Government of Saint Lucia, “SLTB Announces Island wide Hotel Expansion,” Saint Lucia – Access Government, (June 12, 2017), accessed September 2, 2019, https://www.govt.lc/news/sltb-announces-islandwide-hotel-expansion.

- 42Lauretta Burke, Suzie Greenhalgh, Daniel Prager, and Emily Cooper, “Coastal Capital – Economic Valuation of Coral Reefs in Tobago and St. Lucia,” The Economic Valuation of Coral Reefs in the Caribbean. World Resource Institute, 2018.

- 43IMF, “St. Lucia: Staff Concluding Statement of the 2019 Article IV Mission,” International Monetary Fund, (November 18, 2019), accessed December 2, 2019, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2019/11/18/mcs111819-st-lucia-staff-concluding-statement-of-the-2019-article-iv-mission.

- 44Office of the Prime Minister, “Government Renews Commitment to Employment,” Saint Lucia – Access Government, (June 13, 2017), accessed November 20, 2019, https://www.govt.lc/news/government-renews-commitment-to-employment.

- 45Anicia Antoine, “National Apprenticeship Program Students Graduate,” Saint Lucia – Access Government, (October 3, 2019), November 3, 2019, https://www.govt.lc/news/national-apprenticeship-program-students-graduate.

- 46R Miller, et al, Climate Change Adaptation Planning in Latin American and Caribbean Cities Complete Report: Castries, Saint Lucia, 2012: 90.

- 47Government of Saint Lucia, “Saint Lucia’s Sectoral Adaptation Strategy and Action Plan for the Water Sector (Water SASAP) 2018- 2028, under the National Adaptation Planning Process,” Department of Sustainable Development, Ministry of Education, Innovation, Gender Relations and Sustainable Development and Department of Agriculture, Fisheries, Natural Resources and Cooperatives, Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Physical Planning, Natural Resources and Cooperatives, 2018.