By William Reinsch:

Now that the conventions are over and the platforms decided — not that anyone will read or remember them — the serious march to November 8 begins. People who have not been paying attention for the past year or so will begin to focus, probably after Labor Day, and the issues that decide the election will gradually fall into place. For better or worse — probably worse — it appears that trade will be one of them. So, I thought it might be useful from time to time to review the various assertions made by the candidates and assess how close they come to reality. This will not be fact checking (that is better left to Glenn Kessler at the Washington Post). Rather, it is an effort to get the debate out of the current fact-free zone and return it to the real world. And, in the process, perhaps help voters break the code the candidates use and better understand what they are really talking about and what is really at stake.

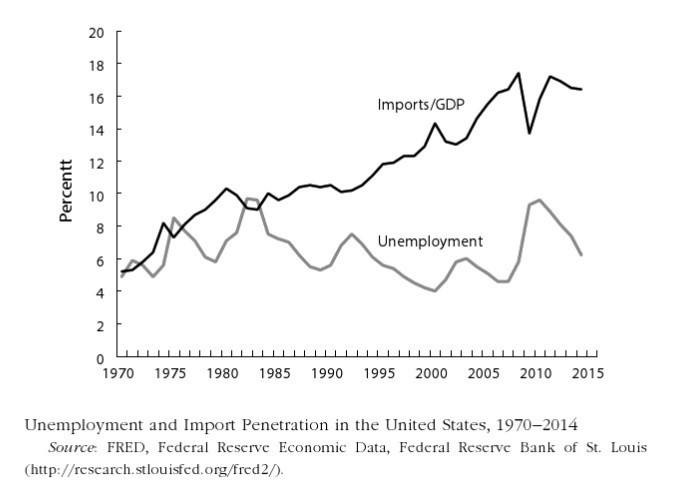

Myth #1 is perhaps the most basic — that trade, or trade agreements, kills jobs. There have been many studies done on this subject over the years, and those by objective parties have come to the same conclusion: the net effect of trade on jobs in the economy is negligible. There are simply too many other factors that are more important. That can be illustrated most clearly and simply via this graph below from Federal Reserve data, which shows that for 35 years unemployment has generally declined as imports as a proportion of GDP have risen. In fact, you can see in both the post-2000 recession and the Great Recession that followed it, unemployment rose while imports declined.

This demonstrates not so much that there is a positive relationship between jobs and trade but that there are other more important factors in the economy that determine the level of joblessness. That should not be a surprise. We have a very dynamic economy, even when growth is sluggish. In 2014, for example, there were 55.1 million job separations (both layoffs and quits) and 57.9 million hires, for a net employment gain of 2.8 million. So, one could say we lost 55 million jobs that year, but that would not be telling the whole story. It is hard to untangle the many reasons why a job may be lost, but the Bureau of Labor Statistics has tried, at least until budget cuts forced it to stop. The bureau found that mass layoffs due to import competition or overseas relocation collectively accounted for 3.5% or less of the total annually from 1996 to 2006. From 2008 through 2011, the percentage of workers laid off due to imports was consistently less than 1%. Clearly, there is more going on here than trade.

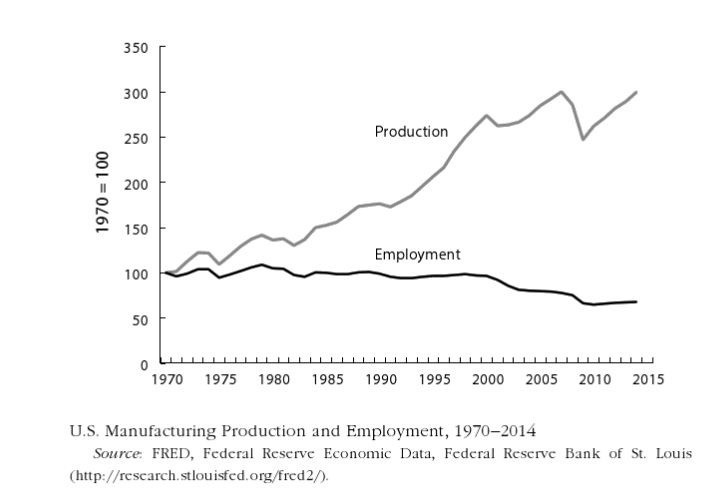

This, of course, is aggregate data. It obscures the fact that trade does cost some jobs, primarily in sectors that compete directly with imports. Some sectors, like footwear, apparel, and furniture, have been decimated by imports over a long period of time to the point where it is hard to find those products that are not imported. Other sectors, particularly in manufacturing, have suffered significant job losses but have maintained output. That suggests once again that there is more going on than trade; primarily technology change that has improved productivity, as our economy continues to become more service-based, which the figure below illustrates. Manufacturing’s share of nonfarm jobs in 1970 was 25%. In 2014 it was 9%.

The anti-trade folks’ response is usually that the lost manufacturing jobs were well-paying and the gained services jobs are not. The truth of that, as usual, depends on how you count. If the manufacturing job is making steel and the services job is behind the counter at KFC, then, yes, there’s a pretty significant disparity. On the other hand, if the latter is being an anesthesiologist, then not so much. BLS data estimates that the average hourly manufacturing wage in June was slightly less than the private services hourly wage, although average weekly manufacturing earnings were higher, suggesting once again that the aggregate covers up a multitude of differences.

Not everyone who has lost a manufacturing job has ended up at KFC, and not all services jobs are entry-level, but that has been true often enough to establish that presumption in people’s minds. Right or wrong, however, the question remains as to the proper policies to address both job loss and income disparity. What I hope readers get out of this piece, if nothing more, is that trade policy solutions by themselves are not the answer. There are simply too many other things going on in the economy that also need to be addressed.

___

William Reinsch is a Distinguished Fellow with the Stimson Center, where he works principally with the Center’s Trade21 initiative.

Photo credit: Eric Kilby via Flickr

Does Trade Really Kill Jobs?

By William Reinsch

In Trade & Technology

By William Reinsch:

Now that the conventions are over and the platforms decided — not that anyone will read or remember them — the serious march to November 8 begins. People who have not been paying attention for the past year or so will begin to focus, probably after Labor Day, and the issues that decide the election will gradually fall into place. For better or worse — probably worse — it appears that trade will be one of them. So, I thought it might be useful from time to time to review the various assertions made by the candidates and assess how close they come to reality. This will not be fact checking (that is better left to Glenn Kessler at the Washington Post). Rather, it is an effort to get the debate out of the current fact-free zone and return it to the real world. And, in the process, perhaps help voters break the code the candidates use and better understand what they are really talking about and what is really at stake.

Myth #1 is perhaps the most basic — that trade, or trade agreements, kills jobs. There have been many studies done on this subject over the years, and those by objective parties have come to the same conclusion: the net effect of trade on jobs in the economy is negligible. There are simply too many other factors that are more important. That can be illustrated most clearly and simply via this graph below from Federal Reserve data, which shows that for 35 years unemployment has generally declined as imports as a proportion of GDP have risen. In fact, you can see in both the post-2000 recession and the Great Recession that followed it, unemployment rose while imports declined.

This demonstrates not so much that there is a positive relationship between jobs and trade but that there are other more important factors in the economy that determine the level of joblessness. That should not be a surprise. We have a very dynamic economy, even when growth is sluggish. In 2014, for example, there were 55.1 million job separations (both layoffs and quits) and 57.9 million hires, for a net employment gain of 2.8 million. So, one could say we lost 55 million jobs that year, but that would not be telling the whole story. It is hard to untangle the many reasons why a job may be lost, but the Bureau of Labor Statistics has tried, at least until budget cuts forced it to stop. The bureau found that mass layoffs due to import competition or overseas relocation collectively accounted for 3.5% or less of the total annually from 1996 to 2006. From 2008 through 2011, the percentage of workers laid off due to imports was consistently less than 1%. Clearly, there is more going on here than trade.

This, of course, is aggregate data. It obscures the fact that trade does cost some jobs, primarily in sectors that compete directly with imports. Some sectors, like footwear, apparel, and furniture, have been decimated by imports over a long period of time to the point where it is hard to find those products that are not imported. Other sectors, particularly in manufacturing, have suffered significant job losses but have maintained output. That suggests once again that there is more going on than trade; primarily technology change that has improved productivity, as our economy continues to become more service-based, which the figure below illustrates. Manufacturing’s share of nonfarm jobs in 1970 was 25%. In 2014 it was 9%.

The anti-trade folks’ response is usually that the lost manufacturing jobs were well-paying and the gained services jobs are not. The truth of that, as usual, depends on how you count. If the manufacturing job is making steel and the services job is behind the counter at KFC, then, yes, there’s a pretty significant disparity. On the other hand, if the latter is being an anesthesiologist, then not so much. BLS data estimates that the average hourly manufacturing wage in June was slightly less than the private services hourly wage, although average weekly manufacturing earnings were higher, suggesting once again that the aggregate covers up a multitude of differences.

Not everyone who has lost a manufacturing job has ended up at KFC, and not all services jobs are entry-level, but that has been true often enough to establish that presumption in people’s minds. Right or wrong, however, the question remains as to the proper policies to address both job loss and income disparity. What I hope readers get out of this piece, if nothing more, is that trade policy solutions by themselves are not the answer. There are simply too many other things going on in the economy that also need to be addressed.

___

William Reinsch is a Distinguished Fellow with the Stimson Center, where he works principally with the Center’s Trade21 initiative.

Photo credit: Eric Kilby via Flickr