By William Reinsch:

Editor’s Note: This is the third in a series of three pieces examining demographic trends and their impact on the global economy. Read Part I: No Country for Old Men? Demography’s Impact on the Global Economy,” and Part II: Into the Great Wide Open: How Millennials Look at Trade.

Last week I discussed the rise of the Millennials and the implications for trade policy. Today I’d like to expand that and look at the impact on partisan politics.

Over the past 150 years, America’s two main political parties’ positions on trade have flip-flopped. In the 19th century, the Republicans were the dominant party in the northeast, and they tended to favor high tariffs that would benefit their manufacturers. Abraham Lincoln, for example, was an unabashed high tariff man. The Democratic Party was particularly strong in the South, where agriculture, including large commodity crops like cotton, dominated. Southerners wanted to export their production and have access to cheaper foreign machinery and therefore tended to favor low tariffs.

This basic division did not change much until the Depression came along and brought Franklin Roosevelt to power. Primarily Republican administrations between 1860 and 1932 pursued protectionist high tariff policies that culminated in the Smoot Hawley tariffs of 1930. Although the tariffs could not be blamed for the Depression, which began a year earlier, by all accounts they clearly contributed to it. Roosevelt, backed by heavy majorities in Congress, transformed U.S. trade policy through the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934 in which Congress ceded considerable tariff negotiating authority to the president and built in a bias in favor of reducing tariffs rather than increasing them. This brought an end to the log rolling tariff policies of the 1920s and earlier where members of Congress backed other’s tariff increases in order to gain backing for their own, and it gave leadership to a president who favored trade liberalization.

While this was a major reversal of U.S. trade policy, it was not a reversal of party positions. The Democrats had always been the low tariff party. The difference was that now they were in power. After World War II, however, over time a significant shift occurred. As the United States became the dominant global economy, exports began to grow in importance, and U.S. business interests became more international. Republican politics began to shift toward freer trade as the internationalist/big business wing of the party came to dominance. Later on their views were reinforced by the conservative wing of the party which viewed tariffs as taxes — i.e. something to be cut — and thought of free trade as part of a smaller government agenda.

Meanwhile, as trade’s share of our economy began to grow, competition from low-priced manufacturing imports, first in textiles and apparel and then in steel and other sectors, became a bigger issue, and organized labor began to move away from its traditional free trade stand towards protection for its workers, just as its members were increasingly concentrated in northeastern and industrial Midwestern states.

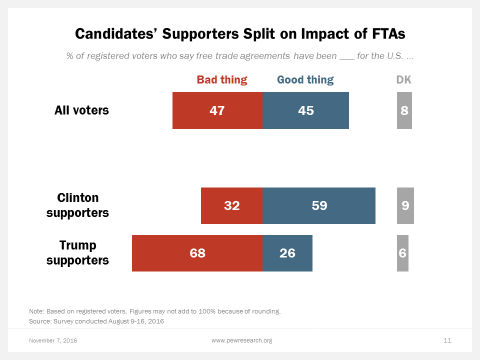

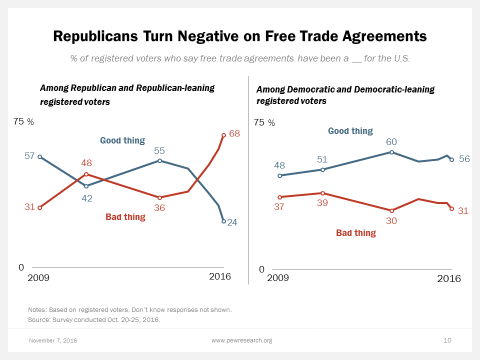

The result was that by the 1970s the two parties had essentially reversed themselves, with the Republicans supporting free trade and the Democrats favoring more protection. Despite the party differences, a bipartisan coalition that generally opposed protectionist legislation prevailed throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s. Only recently has it begun to crumble. This change is reflected in Pew Research Center data, thanks to Bruce Stokes:

This suggests that party positions are flipping once again, although it also seems that both parties’ politicians have not yet caught up with their own voters, since most Democratic members of Congress continue to oppose TPP, and most Republicans support it — or at least they did before the election.

Underlying this change is a broader change of party demographics. Numerous analyses have shown that Trump supporters tend to be whiter, older, and less educated. That is also a description of the group most likely to see itself as a victim of trade and foreign competition, and, as last week’s column noted, the group most likely to oppose trade agreements. Democratic supporters, in contrast, are increasingly minorities, college-educated, and younger.

There is always the possibility that Donald Trump is essentially a wild card — bringing people to the Republican side who would not normally go there and who will leave once he leaves the scene — but it is more likely we are witnessing a significant change in party composition that will last for a long time to come. Looking just at trade, the shift has two implications.

1) Over the long term the part of the population more supportive of trade and trade agreements is growing, and the part opposed to them is shrinking.

2) Both parties have internal conflicts that need to be resolved. Republicans ultimately face a fight for the party’s soul between the Trump wing and the traditional business, conservative and evangelical wings, many of whom are pro-trade (in the short run all are united in victory, but history suggests that won’t last long). On the Democratic side, both organized labor and party leadership will have to sort out their priorities. Labor’s non-trade positions are much more compatible with the Democrats than the Republicans, but as long as opposition to trade is at the top of its list, it will find itself increasingly at odds with a party whose rank and file minority and Millennial members are moving in the opposite direction. And, as occurred last week, it will face growing difficulty delivering its votes for the Democratic ticket when there is a trade-skeptic Republican alternative. Conversely, if Trump attempts to deliver on his trade campaign promises, will we see business moving to the Democrats?

In other words, are we looking at the Republicans becoming the party of protectionism, and the Democrats the party of open trade — going back 100 years? Doubtful — life is rarely that black and white, but it’s an interesting thought to contemplate that will keep pundits and analysts busy for the next few years.

___

William Reinsch is a Distinguished Fellow with the Stimson Center, where he works principally with the Center’s Trade21 initiative.

Photo credit: U.S. Goverment work via Flickr

Back to the Future on Trade?

By William Reinsch

In Trade & Technology

By William Reinsch:

Editor’s Note: This is the third in a series of three pieces examining demographic trends and their impact on the global economy. Read Part I: No Country for Old Men? Demography’s Impact on the Global Economy,” and Part II: Into the Great Wide Open: How Millennials Look at Trade.

Last week I discussed the rise of the Millennials and the implications for trade policy. Today I’d like to expand that and look at the impact on partisan politics.

Over the past 150 years, America’s two main political parties’ positions on trade have flip-flopped. In the 19th century, the Republicans were the dominant party in the northeast, and they tended to favor high tariffs that would benefit their manufacturers. Abraham Lincoln, for example, was an unabashed high tariff man. The Democratic Party was particularly strong in the South, where agriculture, including large commodity crops like cotton, dominated. Southerners wanted to export their production and have access to cheaper foreign machinery and therefore tended to favor low tariffs.

This basic division did not change much until the Depression came along and brought Franklin Roosevelt to power. Primarily Republican administrations between 1860 and 1932 pursued protectionist high tariff policies that culminated in the Smoot Hawley tariffs of 1930. Although the tariffs could not be blamed for the Depression, which began a year earlier, by all accounts they clearly contributed to it. Roosevelt, backed by heavy majorities in Congress, transformed U.S. trade policy through the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934 in which Congress ceded considerable tariff negotiating authority to the president and built in a bias in favor of reducing tariffs rather than increasing them. This brought an end to the log rolling tariff policies of the 1920s and earlier where members of Congress backed other’s tariff increases in order to gain backing for their own, and it gave leadership to a president who favored trade liberalization.

While this was a major reversal of U.S. trade policy, it was not a reversal of party positions. The Democrats had always been the low tariff party. The difference was that now they were in power. After World War II, however, over time a significant shift occurred. As the United States became the dominant global economy, exports began to grow in importance, and U.S. business interests became more international. Republican politics began to shift toward freer trade as the internationalist/big business wing of the party came to dominance. Later on their views were reinforced by the conservative wing of the party which viewed tariffs as taxes — i.e. something to be cut — and thought of free trade as part of a smaller government agenda.

Meanwhile, as trade’s share of our economy began to grow, competition from low-priced manufacturing imports, first in textiles and apparel and then in steel and other sectors, became a bigger issue, and organized labor began to move away from its traditional free trade stand towards protection for its workers, just as its members were increasingly concentrated in northeastern and industrial Midwestern states.

The result was that by the 1970s the two parties had essentially reversed themselves, with the Republicans supporting free trade and the Democrats favoring more protection. Despite the party differences, a bipartisan coalition that generally opposed protectionist legislation prevailed throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s. Only recently has it begun to crumble. This change is reflected in Pew Research Center data, thanks to Bruce Stokes:

This suggests that party positions are flipping once again, although it also seems that both parties’ politicians have not yet caught up with their own voters, since most Democratic members of Congress continue to oppose TPP, and most Republicans support it — or at least they did before the election.

Underlying this change is a broader change of party demographics. Numerous analyses have shown that Trump supporters tend to be whiter, older, and less educated. That is also a description of the group most likely to see itself as a victim of trade and foreign competition, and, as last week’s column noted, the group most likely to oppose trade agreements. Democratic supporters, in contrast, are increasingly minorities, college-educated, and younger.

There is always the possibility that Donald Trump is essentially a wild card — bringing people to the Republican side who would not normally go there and who will leave once he leaves the scene — but it is more likely we are witnessing a significant change in party composition that will last for a long time to come. Looking just at trade, the shift has two implications.

1) Over the long term the part of the population more supportive of trade and trade agreements is growing, and the part opposed to them is shrinking.

2) Both parties have internal conflicts that need to be resolved. Republicans ultimately face a fight for the party’s soul between the Trump wing and the traditional business, conservative and evangelical wings, many of whom are pro-trade (in the short run all are united in victory, but history suggests that won’t last long). On the Democratic side, both organized labor and party leadership will have to sort out their priorities. Labor’s non-trade positions are much more compatible with the Democrats than the Republicans, but as long as opposition to trade is at the top of its list, it will find itself increasingly at odds with a party whose rank and file minority and Millennial members are moving in the opposite direction. And, as occurred last week, it will face growing difficulty delivering its votes for the Democratic ticket when there is a trade-skeptic Republican alternative. Conversely, if Trump attempts to deliver on his trade campaign promises, will we see business moving to the Democrats?

In other words, are we looking at the Republicans becoming the party of protectionism, and the Democrats the party of open trade — going back 100 years? Doubtful — life is rarely that black and white, but it’s an interesting thought to contemplate that will keep pundits and analysts busy for the next few years.

___

William Reinsch is a Distinguished Fellow with the Stimson Center, where he works principally with the Center’s Trade21 initiative.

Photo credit: U.S. Goverment work via Flickr