The Red cell project

The Red Cell was a small unit created by the CIA after 9/11 to ensure the analytic failure of missing the attacks would never be repeated. It produced short briefs intended to spur out-of-the-box thinking on flawed assumptions and misperceptions about the world, encouraging alternative policy thinking. At another pivotal time of increasing uncertainty, this project is intended as an open-source version, using a similar format to question outmoded mental maps and “strategic empathy” to discern the motives and constraints of other global actors, enhancing the possibility of more effective strategies.

Reimagining Assumption: The world is now at an inflection point, demanding original, unheard-of solutions that bear little resemblance to past efforts.

Today the United States is facing a “strategic inflection point,” according to former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Mark Milley. President Joe Biden agrees, declaring that the U.S. is at an “inflection point in history.” President Barack Obama said the same on multiple occasions in 2016, as did former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Martin Dempsey in 2011. For the term “inflection point” to have any meaning, not all these assessments could have been correct.

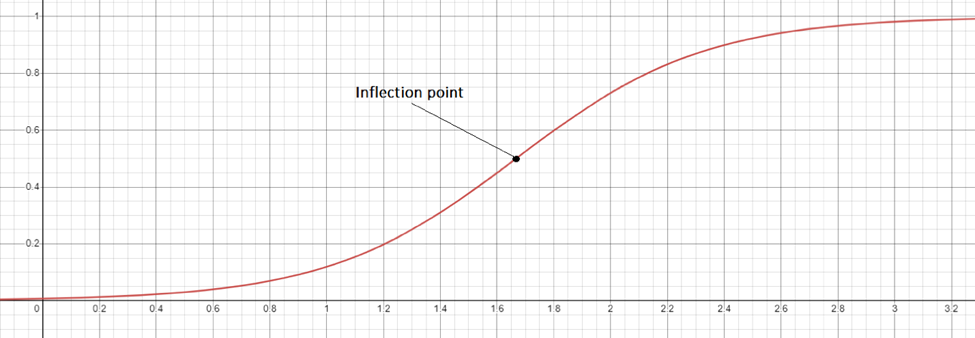

“Inflection” refers to a change in the concavity of a curve. Imagine an S-curve. The inflection point is in the middle of the S, where the slope of the curve transitions from increasing rapidly to increasing more slowly or even decreasing. When top national security figures make frequent reference to inflection points, it suggests a situation more like a sine wave, where inflections – which occur each time a curve oscillates upward and downward – are the norm rather than the exception. Such a routine occurrence does not appear to align with the narrative flair of the term “inflection point” as used by U.S. leaders.

What do data on macro trends reveal? Global population growth has already passed its inflection point, increasing at a slower rate relative to several decades ago; indeed, population growth is expected to turn negative by the end of this century. Global economic activity is more difficult to forecast but shows no obvious sign of inflection. Bilateral goods trade, in particular, has been characterized by a great deal of continuity in the post-World War II period despite periodic geopolitical shocks. If the world is lucky, global average temperatures will continue to head toward an inflection point, as they appear to be doing.

China’s new period of slower economic growth and a shrinking population are forecasted to produce smaller and smaller increases in its national power during the coming decades, while the United States continues to experience a relative decline in its national power. These trends are continuing after their inflections have come and gone, having already passed through the mid-point of their respective s-curves. Even use of the term “inflection point” appears to have passed its inflection point in terms of the number of times it is mentioned in books, according to Google’s Ngram viewer.

Certainly, immense changes are underway in many low- and middle-income countries. The International Futures tool, a forecasting model housed at the Pardee Center at the University of Denver, forecasts that the percentage of the population in poverty in non-Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries will shrink from roughly one-quarter of today’s population to half of that in percentage-point terms in the next 20 years. Meanwhile, many countries will see the size of their middle class grow — along with the pressures for better governance and democratization that accompany this trend.

Alongside these changes, the calls for reform of international institutions — perhaps even a re-working of the “plumbing” of the international system altogether — will rightfully grow louder. But the results of these reforms can be expected to reflect more continuity than change, with the fundamental operation of international politics remaining largely similar. For example, a joint statement from Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa in August 2023 called for “a comprehensive reform of the UN” — but not an abandonment of the United Nations concept generally.

Technology may be a more notable exception. This is an interesting time where Moore’s law — the annual doubling of the number of transistors of a microchip, making computers smaller, cheaper, and faster — is dead or dying, but increases in artificial intelligence (AI) computational power are accelerating. From upending and creating new business models to revolutionizing personal planning to redistributing power across societies, AI undoubtedly has the potential to fundamentally transform the world. But if it does, this phenomenon will be the exception that proves the rule.

The desire to assert that the present era is entirely unique or unprecedented appears to be ingrained into human nature. In the extreme, this has manifested in various predictions of an impending Armageddon, which date back at least roughly 2,000 years. This tradition has carried through to today, where a sense that “the end is nigh” with respect to the Israel-Hamas war has captured the imaginations of some American Evangelicals and others ready to embrace the end times.

Believing that today is somehow a truly special moment in world history — although potentially making today’s global citizens feel special — clouds strategic thinking. If today’s challenges are novel, they require novel solutions. Except what if they are not so novel and old solutions work just fine?

The End of History Is Still Sometime in the Future

Although comparisons between today’s US-China competition and the US-Soviet Cold War should not be overstated, many lessons of the past are just as applicable to the present. Take, for example, then-soon-to-be director of the Pentagon’s Office of Net Assessment Andrew Marshall’s advice in 1972 on competitive strategy, which may as well have been written yesterday with respect to an American national security establishment reckoning with the post-Post-Cold-War era:

In the past the United States could afford to employ a rich man’s strategy against a weaker opponent. This can no longer be done. With an essentially fixed stream of resources to use in developing, procuring, and operating strategic forces, a continuation of high-cost hedges against all possible threatening developments will soon exhaust the totality of available resources.

An otherwise excellent report recently published by the RAND Corporation — Inflection Point: How to Reverse the Erosion of U.S. and Allied Military Power and Influence — similarly provides policy prescriptions that are not unique to today’s times. To wit, the need to “ensure that inventories of preferred munitions and other consumables are sufficient to carry out continued strikes against enemy forces” is not really new — it is re-learning lessons from industrial warfare of the past. Indeed, the authors note, “The year 2022 is not 1947, but important elements of that earlier time are very much present today.” In other words, today’s global situation is more of the same persistent challenges, not to say that facing “the same” is necessarily any less demanding as navigating through new challenges.

Overstating the uniqueness of the present geopolitical situation can lead policymakers to overlook similarities with the past. For example, recent talk of America’s so-called hypersonic missile “gap” closely parallels the intercontinental ballistic missile “gap” hysteria of the 1950s and 1960s. Although “Sputnik moments,” “disruption,” and “black swan” events may be exciting to talk about, the truth is that today’s world is experiencing far more continuity than change — and most of the latter in the form of slow-moving, relatively continuous change. A fixation on discontinuous shocks leads to many “high-cost hedges,” in Marshall’s words, to the detriment of other priorities. For example, during the Cold War, Marshall successfully encouraged the U.S. military to “push innovation in technology vigorously” to draw the Soviets into largely unnecessary technology races; force tradeoffs between research and development versus operations, maintenance, and procurement; and further strain an already strained Soviet military budget.

A true geopolitical inflection point may merit some, perhaps even a lot, of hedging. But, as Marshall warns, hedging can be costly, and a wily opponent (such as the United States competing with the former Soviet Union) can take action to make it costlier. Even in the absence of a hedging strategy, calling geopolitical inflection points accurately has immense implications for U.S. national security strategy, helping to inform whether a short-, medium-, or long-term strategy toward research and development and procurement is warranted. An inflection point is an excellent time to pivot strategies to maximize effectiveness in the medium or long term, once the effects of the inflection become noticeable. However, such a pivot would undermine short-term readiness.

Odds are, any given point in time is not an inflection point — unless geopolitics is best expressed by a sine wave, in which case there is still continuity in the patterns of change. The reality that some of the present U.S. predicaments with China resemble those with the former Soviet Union does not undermine the importance of today’s national security challenges. But it does suggest that today’s circumstances are not entirely unique, and decision-makers can learn from past mistakes. Present trends may be more knowable than some people may like to think. And old playbooks may work just fine to guide the tackling of today’s challenges.

This is not to say that old playbooks would not sometimes benefit from an update. For example, along with the United Nations, the Bretton Woods institutions — the International Monetary Fund and World Bank — are long overdue for a serious refresh in terms of voting power and other reforms. But their fundamental roles in the international system remain vital.

Nor is this to say that old playbooks alone will always suffice. Still, lessons learned from great powers’ responses to the threat of nuclear proliferation could, for example, provide helpful analogs for the proliferation of AI-enabled autonomous weapons systems today. The successes of the Geneva Protocol of 1925 — the Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or other Gases, and Bacteriological Methods of Warfare — and later the Chemical Weapons Convention, effective as of 1997, provide other examples of how governments have proven able to join together to substantially limit the potential damage of extraordinarily dangerous and relatively easily accessible technologies.

To be sure, the world does at times pass through inflection points — and today’s advancement toward general AI may be one of them. But not every development is an inflection point. Policymakers must have the wisdom to know the difference or risk “inflection-point fatigue.” If fatigue sets in, calls for historic responses to a challenge because “this time it is different” will be ignored – even if, for that unique “this time,” it actually is different.