The Red cell project

The Red Cell was a small unit created by the CIA after 9/11 to ensure the analytic failure of missing the attacks would never be repeated. It produced short briefs intended to spur out-of-the-box thinking on flawed assumptions and misperceptions about the world, encouraging alternative policy thinking. At another pivotal time of increasing uncertainty, this project is intended as an open-source version, using a similar format to question outmoded mental maps and “strategic empathy” to discern the motives and constraints of other global actors, enhancing the possibility of more effective strategies.

“The idea that a ‘new Washington consensus,’ as some people have referred to it, is somehow America alone, or America and the West to the exclusion of others, is just flat wrong. This strategy will build a fairer, more durable global economic order for the benefit of ourselves and for people everywhere.” – Jake Sullivan, April 2023

There may be a new consensus in favor of national industrial policies where national security imperatives shape economic decisions and geopolitics dictates de-risking and working with economic partners whose values align with Washington’s. But the assumption that these trends will lead to a more stable and prosperous world appears flawed. Instead, the evidence points to the deepening erosion of the global economic system and its fragmentation, which is likely to reinforce great power competition ― Cold War 2.0 ― and increase the likelihood of conflict among major powers.

The current situation is a backlash from the excesses of hyper-globalization, which generated both prosperity and wealth disparities within nations (e.g., the hollowing out of U.S. manufacturing) and among nations. Today new patterns, including the bifurcation of policy-driven trade, capital, and technology flows, as well as weaponized interdependence (tariffs, sanctions, export controls), have unraveled the economic integration and connectivity brought about by the past era of globalization.

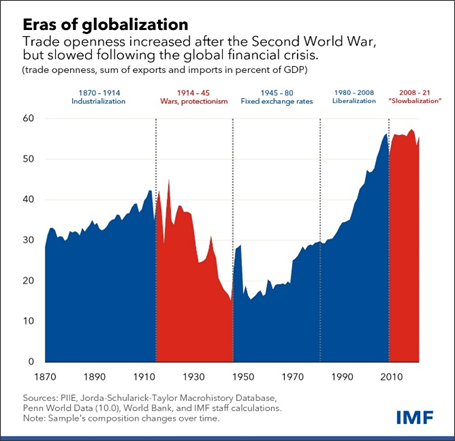

Current dynamics are often referred to as deglobalization. But this is an oversimplified or at least, premature assessment: The flow of ideas, goods, capital, and people across borders continues. Instead, the data suggest a new pace and direction of flows, a new geometry of trade and investment, or as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) calls it, “slowbalization”: near-flat growth and region– and bloc-centric trade in goods and investments as well as slow globalized trade in services.

For context, world trade grew 4,500% from 1950 to 2022. The high point was the explosion of trade liberalization as the Cold War dissipated, from about 1989 to 2008. During this period, complex supply chains deepened economic integration, the poverty level of billions of people in the developing world was reduced, and a new global middle class was created, but inequality within and among nations intensified. The set of rules and norms known as neoliberalism — deregulation, market-based trade and investment openness, and economic decisions aimed at increasing efficiency, as well as an expansion of the post-World War-II global order to include post-Soviet Eurasia and the Global South, fostered this burgeoning interdependence.

But then came the backlash. The “China shock” occurred as the country’s economy experienced rapid economic growth, which accelerated following China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2000; as a result, some 2 million American jobs were lost, as Beijing gamed the system to become the “world’s factory.” The fallout from the 2008 financial crisis and the ensuing Great Recession changed U.S. policymakers’ views on the costs and benefits of deregulated capital flows. Meanwhile, China’s stunning growth altered many analysts’ views of the risks of free trade. And the supply chain disruptions that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as currently with the Ukraine War, have deepened skepticism about the neoliberal experiment.

Trade restrictions — tariffs, as well as nontariff measures (e.g.; export controls, quotas, sanctions) — increased five-fold from 524 in 2015 to 3,000 in 2023. Unlike the collapse of the previous era of globalization after World War I, when world trade shriveled, in recent years global trade as a percentage of world GDP has been largely static, oscillating between 55% and 60% of world gross domestic product, a reflection of the complex web of economic integration. But in assessing the rise in tariff and nontariff barriers to trade and investment, the IMF has raised concern over what its modeling depicts as a trend of “geoeconomic fragmentation” of the multilateral system, which it fears could reduce global GDP over time by up to 7% if the system fragments into US-EU-Japan and China-Eurasia-Global South.

This reflects the growing national securitization of both investment and trade. Former President Donald Trump’s anti-China trade war rhetoric during the 2016 presidential elections reflected a bipartisan shift. In response to Chinese overproduction, Trump imposed sweeping tariffs on steel and aluminum imports — not just from China, but also on certain imports from U.S. allies Canada, the European Union (EU), and Japan. This triggered massive retaliation. Trump expanded 25% tariffs to apply to some $300 billion in Chinese goods and also initiated restrictions on Chinese tech exports and investment in the United States, as well as on some U.S. investments in China.

Biden has maintained and expanded Trump’s China tariffs and has imposed bans on U.S. outward tech investment in China and on U.S. high-end chips and chipmaking equipment; these moves have been aimed at creating chokepoints to cut off China’s path to top-end semiconductors. The centerpiece of this industrial policy is a state-backed investment strategy of subsidies and tax credits for Buy/Make in America technologies, focused on renovating U.S. manufacturing in semiconductors and clean energy technologies. This effort is embodied principally in three major acts: the $2-trillion Bipartisan Infrastructure Deal; the $280-billion CHIPS and Science Act;1 CHIPS stands for Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors. and the misnamed Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which authorizes some $300 billion in spending for clean energy technologies and climate change mitigation.

The overarching dynamic of US-China strategic competition is one of surging ideologically based economic nationalism. Biden has sought to fashion a mainly “democracies-only” organizing principle for mobilizing trade, technology, and investment coalitions. Thus, G-7 statements reflect commitments to cooperate on supply chains and develop trustworthy technologies. Similarly, coalitions of democracies in nonbinding initiatives like the Critical Minerals Partnership, the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, and the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Technology Council seek friendshoring, resilient supply chains and cooperation on technology standards. Underscoring the shift away from a global trade regime, the United States has made little effort to reform the WTO and address key issues such as subsidies. This was underscored by the meager outcome of the WTO’s recent 13th Ministerial Conference: U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai left early.

Contradictions Among Policies

Although it is premature to judge the success of Biden’s nascent industrial policies with its Buy/Make in America requirements — like Made in China 2025, Make in India, and EU industrial policies — the impact of these competing economic nationalistic approaches to global trade, technology, and investment are already discernable. In what appears to be a structural shift, U.S. trade with Mexico recently surpassed U.S. trade with China, while U.S. imports from China declined by 20% — by $100 billion — in 2023. This trend could also highlight the difficulty of geopolitically rewiring supply chains: U.S. firms are pursuing a “China-plus-1” strategy to gradually de-risk, moving some production to third countries, notably India and Vietnam. But these two countries are often assembling intermediate components from China into final products, thereby lengthening supply chains as their exports to the United States increase in rough proportion to the decline of their imports from China.

With China as the world’s largest trading power, accounting for $6 trillion in annual two-way trade in 2022, disentangling supply chains is a difficult and long-term proposition. China now trades more with the Global South, Russia, and Central Asia than it does with the United States, the EU, and Japan combined. A recent McKinsey study of the reconfiguring of trade found that trade between G-7, and the China-Eurasia blocs has declined 4-10% since 2017, while trade within blocs has been increasing.

Some of the unintended consequences of U.S. industrial policies are mirror-image actions, not just in China’s moves toward economic autarky, but also by the EU, suggesting that economic coalitions of like-minded democracies have limitations. The subsidies and tax credits in the CHIPS and Science Act and the IRA have reportedly incentivized more than $200 billion in announced private investment in U.S. manufacturing and construction. The $7,500 tax credit offered in the IRA to consumers buying American-made cars initially excluded European, Japanese, and Korean auto factories in the United States, angering these U.S. allies. In response, Biden created a temporary loophole: Foreign firms manufacturing in the United States and using foreign components can offer consumers full access to the tax credits if consumers lease, rather than buy the vehicles.

Such tensions ripple through U.S. industrial policies. Fearing that U.S. policies might lure European tech firms away, the EU launched its own $47-billion CHIPS act to expand European semiconductor manufacturing, and in response to the IRA. Furthermore, the EU launched a new Net-Zero industry plan to reach 40% production of its own green tech by 2030, while bolstering its own Green Deal. Like China, the EU could avoid using U.S. tech in the future, designing its own components and products to avoid U.S. tariffs or sanctions. It is difficult to gauge how this competition might play out, as U.S. semiconductor and clean tech investments have been slow to materialize, with new chip fabs not expected before 2028. Similarly, both critical minerals and their processing, as well as manufacturing of green tech — over 80% of the solar supply chain, electric vehicles (EVs), and batteries — are dominated by China. Implementing U.S. climate goals – 100% clean electricity by 2035 and EVs comprising over 50% of vehicle sales by 2030 — without using Chinese tech will require the United States and the EU to develop alternate sources of minerals and components. This will increase costs and delay the green transition.

Some U.S. policymakers are concerned that in terms of competition with China, U.S. industrial policy might be having a boomerang effect, accelerating the Chinese tech capacity it seeks to slow. Though Huawei and Chinese semiconductor firm SMIC have been central targets of U.S. tech blockade statecraft, many were shocked when Huawei rolled out a smartphone with an advanced 7-nanometer chip last fall. By 2030, China plans to invest $150 billion in its own semiconductor industry. Beijing wants to find workarounds to the ban of top-end artificial intelligence chips and chipmaking equipment, but the Chinese government also wants to reduce its dependence on foreign chips: more broadly, China imported $349 billion in semiconductors and $40 billion in chipmaking equipment in 2023. U.S. chip firms, which control roughly 50% of the world market, are heavily dependent on the Chinese market and could lose 16% of their market share as well as 37% of their profits from decoupling of the industry over the next 3 to 5 years, according to the Boston Consulting Group.

Similar shifts are occurring regarding capital flows. In 2023, China experienced the lowest foreign direct investment (FDI) in 30 years, with net negative outflows from disinvestment, and with as much as a net $500 billion in both Chinese and foreign investors’ capital leaving China. This appears to reflect the confluence of several factors: U.S. and EU de-risking strategies, draconian Chinese national security and intelligence laws, curbs on cross-border data flows, a clampdown on foreign due-diligence firms assessing risk for prospective investors, and an apparently arbitrary crackdown on Chinese Big Tech and its private sector writ large.

There are also increasing hints of financial fragmentation as China itself de-risks. Gita Gopinath, IMF deputy managing director, lamented that there are “clear signs that global FDI is segmenting along geopolitical lines.” Moreover, Beijing’s effort at de-dollarization, facilitated by the expansion of the Brazil, Russia, India, South Africa (BRICS) group and financial sanctions on Russia, is growing, if incrementally. Some 49% of China’s bilateral trade is now done in Renminbi (RMB), much in commodity trade with developing nations; 35% of exports to Russia and 44% of Russian foreign exchange transactions are in RMB. However, constrained by Beijing’s own capital controls, as a share of global payments currency, the RMB still only accounts for 2.5% compared to a combined 75% for the dollar and the Euro. And not least, China’s de-risking during the past decade has reduced its exposure to U.S. Treasuries (from $1.3 trillion to $782 billion) with its overall share of U.S. Treasuries declining from 14% to 3%.

Conclusion

For both the Trans-Atlantic and global economies, the economic trends described above imply a more problematic economic future and great power competition more prone to confrontation. The momentum of economic nationalism and fragmentation is not abating; rather, it continues incrementally — despite a $100-billion decline from all the tariffs and export curbs, US-China trade was $575 billion in 2023. Disentangling complex supply chains is a long-term proposition. China has issued a directive to remove all U.S. IT equipment and software from government devices by the end of the decade. Instead of seeking to balance its excess savings with consumption, Beijing’s new economic plan appears to be to shift state-driven investment from real estate and infrastructure to manufacturing in order to try to export its way out of economic malaise. It is gearing up to flood global markets with solar panels, EVs, batteries, and increasingly legacy semiconductors, too.

On the other side of the Pacific, in his recent State of the Union speech, Biden doubled down on his Make-in-America industrial polices. At the same time, the United States is putting more pressure on the EU and Japan to further cut tech exports to China. And, looking ahead to the November U.S. elections, Donald Trump is promising major new tariffs — 10% on all imports and 60% on Chinese goods. A new cycle of tariffs and Chinese retaliation is likely if Trump wins the election.

Some discontinuity — a global financial crisis, a war in Taiwan, Chinese economic ruin — could alter this trajectory. But the path of economic statecraft, which is increasingly characterized by beggar-thy-neighbor policies, suggests steady, incremental fragmentation, a withering of WTO and global norms, and the formation of two decreasingly overlapping trade and financial networks, exacerbating increased geopolitical tensions. China is moving toward more economic autonomy — aiming to make the world more dependent on Beijing, and China less dependent on the world. Its upward trajectory of trade and investment with Russia and the former Soviet republics, the Middle East, and the Global South will continue. The expansion of the BRICS reflects this trend. The prospect of restrictions and/or 25% or more U.S. and EU tariffs on Chinese EVs, solar panels, and other tech goods is likely. Biden’s intended ban on Chinese EVs on national security grounds owing to cybersecurity risks reflects this trend as well; the EU is studying this.

U.S. and EU trade and tech trajectories suggest a North America-EU-ROK-Japan-plus alternative to Chinese supply chains (e.g., India, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, Mexico) networks and trade clusters. As the China-Eurasia-Global South cluster grows, the sinews of interdependence erode as a bifurcation between these clusters takes shape. The U.S. and EU face a dilemma resulting from Beijing’s success: The more autarchic China becomes as a result of trade and tech wars, the less leverage the West has over Beijing.

Nonetheless, differing approaches to trade and regulatory cultures will be a source of US-EU friction. The EU still looks more to the WTO and global rules than Washington does. Furthermore, U.S. subsidies are luring EU manufacturing investments, placing EU competitiveness at risk. Even though EU skepticism about China has led to closer US-EU alignment, U.S. pressure on the EU to choke off high-end tech trade remains a source of tension. The United States has reneged on its own Indo-Pacific Economic Framework digital trade initiative, walking back positions to prohibit curbs on cross-border data flows, data localization, and source codes and algorithms.

On a global scale, this retreat could jeopardize the WTO’s efforts to reach an e-commerce agreement. More broadly, there is bipartisan U.S. anti-trade sentiment, while the EU is actively pursuing interregional free trade agreements with India, Indonesia, MERCOSUR,2 MERCOSUR is the Southern Common Market, known by its Spanish abbreviation. Mexico, and Chile, among others. This highlights that trade expansion will be plurilateral rather than global and that the WTO’s role as rule-setter and referee is likely to wither. A consensus does not yet exist on sustainable trade issues such as an EU shift to green steel, cement, or aluminum leading to carbon offset taxes for dirty manufacturing, as well as logging and mining, on the Trans-Atlantic agenda; the loser will most likely be the Global South.

The strategic consequences of these dynamics are increasingly problematic for cooperation on global governance, which is needed to reverse fragmentation. The consequences do not apply only to issues like climate change, outer space, technology standards, and global health, but also to updating and reforming key multilateral institutions — the WTO, IMF, and World Bank — as well as managing the debt of less-developed nations, 37% of which is held by Chinese banks. At this juncture, the chances for a stable, prosperous world order have diminished as the global predicament begins to resemble the 1930s redux.

The Red Cell thanks the Swedish Defence University for its support in the research and writing of this article.

Notes

- 1CHIPS stands for Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors.

- 2MERCOSUR is the Southern Common Market, known by its Spanish abbreviation.