Acknowledgments

Any major research project draws input from many capable hands (and brains), but this strategy paper was truly a group effort.

I want first to recognize the contributions of Mathew Burrows, founder and co-director of the Atlantic Council’s New American Engagement Initiative (NAEI), and now the program lead of the Stimson Center’s Strategic Foresight Hub. Mat and I worked together on this paper for months, and the final draft retains many elements from that original work, though the prose is now mostly my own (for better or worse). I am so grateful to Mat for his intellectual leadership, for getting NAEI off the ground, and for being a wonderful colleague and mentor.

NAEI brought together a unique team of creative thinkers, who now all reside in the Stimson Center’s Reimagining US Grand Strategy Program. This paper has benefited throughout from their input. I thank Emma Ashford, Evan Cooper, Aude Darnal, Kelly Grieco, Robert Manning, and James Siebens for carefully reading previous drafts and offering perceptive and timely recommendations for improvement. I am especially grateful to Will Walldorf for his careful read of the entire paper, and for his very helpful comments and suggestions. Thanks also to Peter Huang, Rupert Schulenburg, and Hunter Slingbaum for research help, and to Elizabeth Arens for several rounds of expert copy editing.

Christopher Preble

January 2024

Executive Summary

The era of U.S. global dominance is over. The last decade has demonstrated the grievous mismatch between U.S. ends and means. The failures in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya show the limits of U.S. military power, while the neglect of the homeland has exacerbated political and social divides. More recently, Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine, China’s growing assertiveness, and renewed conflict in the Middle East are all stark reminders that the United States alone cannot maintain peace and security in every corner of the globe; it must share the burden with other states. Global challenges cry out for global solutions.

Evidence of the need for change is abundant. Attempts to maintain U.S. primacy will fail — and erode America’s standing and effectiveness on the world stage. Leadership begins with getting the United States’ own house in order.

What follows is a wholesale reimagining of U.S. national security strategy aligned to today’s world, not an idealized past. This paper begins by establishing the need to change course. Rather than attempting to maintain U.S. dominance, the United States must, above all else, set priorities, with a laser focus on the overarching goals of security, prosperity, and freedom for the American people. In an era of constrained federal budgets and limited public support for ambitious foreign policies that would draw resources away from domestic needs, U.S. policymakers should rethink which national security policies must continue as before, which should be modified, and which should be abandoned in favor of different policies suited to the present era.

Having established the flaws with the dominant strategic paradigm of the last three decades, this paper then identifies ways to achieve Washington’s core objectives while minimizing costs and risks. Failing to set priorities and continuing to ignore persistent economic deficits and looming debt could drive down confidence in the U.S. dollar and undermine the true sources of American power and influence: diplomacy and economic power. Ignoring public sentiment vis-à-vis foreign policy would also expand the already yawning gap between the American people and the elites that purport to represent their interests and be their advocates.

The greatest danger of all, however, is the return of a great-power war. This strategy paper rejects the nature of both the Trump and Biden administrations’ approach to managing competition with China, including restricting Chinese access to certain U.S. and global markets and blocking certain U.S. investments in China. This strategy has already led to retaliatory moves by Beijing. Such tit-for-tat measures can easily escalate, potentially creating severe economic consequences or even military confrontation. Though the current climate in both Beijing and Washington is unlikely to produce a policy shift, long-term U.S. interests would be better served by finding ways to lower tensions and cooperate despite deep differences. Such an approach would pave the way for addressing climate change, poverty, disease, and other global challenges. A refusal to choose among competing goals increases the risk that minor disputes will escalate into wider conflict. Prioritization is essential here as well. By differentiating vital interests from peripheral ones, and demonstrating a capacity and willingness to compromise, U.S. policymakers can establish a foundation conducive to Americans’ prosperity and security, rather than one tending toward overreach and ruin. The forward-leaning paradigm spelled out here differentiates between the ways of the past and new approaches suited to the current era. It is intended to help policymakers adapt their thinking and better assess the costs and risks of various policy options (see Table 1).

Table 1 – Old Think vs. New Think

| Issue | Old Think | New Think |

|---|---|---|

| Strategic paradigm | Liberal hegemony; United States as the indispensable nation. | Humility and restraint: The United States must work with others on big global challenges. |

| Hard choices | Avoid them — doing so is essential to maintaining U.S. dominance in all regions, at all times. | Inevitable — crafting a credible strategy entails reconciling ends, ways, and means as the United States faces challenges at home and probable slower economic growth. Strategists must prioritize. |

| U.S. economic power | Even as the relative weight of U.S. economic power lessens, US-dollar dominance provides leverage over others. | Economic power is vast but limited, and the U.S. economic position is fragile and susceptible to being undermined by both hubris (overuse) and neglect (from internal decay and political paralysis). |

| U.S. military superiority | The lynchpin of global peace and prosperity. | A blunt instrument that often crowds out more effective instruments of American power. |

| China | The preeminent challenger that must be defeated at all costs. | A global powerhouse. Avoiding a catastrophic war with China is a primary objective of this strategy. U.S. policy should focus on finding areas of convergence. A weak/failing China benefits no one. |

| Russia | An irreconcilable global menace. | An opportunistic spoiler. Although it will be impossible to restore constructive relations as long as Vladimir Putin rules Russia, the medium- to long-term aim of U.S. policy should be to draw Russia back from a de facto alliance with China and encourage Russia’s eventual integration into the European security order. |

Given the United States’ limited resources, policymakers should work to construct a new global compact that does not rely on sustaining overwhelming U.S. power in all places, and at all times. They should reimagine U.S. power in a multipolar world of many capable actors and work with allies and partners to redistribute defense burdens and costs. Policymakers should focus on reducing the risk of conflict and eliminating barriers to commerce. This strategy calls for rebalancing the US-foreign-policy toolkit by elevating diplomacy, trade, and cultural exchanges, and by deemphasizing the use of force and coercion. Specifically, the United States should:

- Invest in Diplomacy, Including Public Diplomacy. For most of American history, U.S. leaders relied on diplomacy to extend U.S. influence and secure vital U.S. interests. In the latter half of the 20th century, however, diplomacy was often supplanted by U.S. military power. If diplomacy is to again become a leading tool for advancing U.S. interests in an increasingly complex world, the State Department needs to be fully resourced. Consistent and reliable two-way communication between government agencies and the public is critical to establishing a broad and durable consensus on foreign affairs. Absent sufficient outreach to the public, U.S. foreign policy will remain a “black box” to most Americans.

Since 1999, the United States has lacked a central clearinghouse to coordinate messages across all government agencies, a role formerly filled by the United States Information Agency (USIA). Person-to-person and cultural exchanges have also dwindled. Although U.S. politics and policies are not always popular in other countries, U.S. science and culture usually are. And the benefits flow in both directions. Bringing scientists, artists, and performers to the United States from abroad helps Americans to get to know others from diverse backgrounds.

- Fine-Tune US Economic Power for Greater Influence. This strategy also emphasizes the importance of trade, both to advance U.S. competitiveness and prosperity and because trade is conducive to peace. For the United States to retain its role as a leader in the digital economy, Washington needs to define rules and regulations on data services to ensure interoperability and prevent the growth of hidden sources of protectionism as well as economic and trade fragmentation. At the same time, U.S. policymakers should anticipate domestic skepticism of trade agreements and explain to the American people that jobs in a dynamic economy are more likely to disappear due to technology and innovation than to be outsourced to other countries. Erecting barriers to trade would raise the cost of goods and place other stresses on the economy that could drive down the demand for labor.

The alternative of “managed competition,” in which parties to trade agreements commit to certain purchases from certain suppliers, risks reducing global growth and productivity, particularly in new areas for trade such as e-commerce and digital services. Currently, the three key global digital actors — China, the European Union (EU), and the United States — appear to be evolving into separate and not entirely compatible digital regimes, a potential harbinger of a global economy fragmenting into competing blocs.

Moreover, U.S. policy should avoid unnecessary or arbitrary restrictions on trade. Sanctions should remain part of the U.S. policy arsenal, but emerging trends are likely to reduce their effectiveness. Overuse or misuse of sanctions may reveal U.S. impotence, rather than U.S. power.

- Become a Magnet for the World’s Talent. The world’s talent has long sought to come to the United States to be educated, find employment, and raise families. The United States can often have the pick of the highly skilled, an increasingly valuable asset as countries in Europe and Asia are aging quickly and also competing for the best and brightest. Nevertheless, U.S. universities could forfeit their advantage — and billions of dollars — if they are forced to turn away foreign students. Such a move would also hurt U.S. innovation because a majority of new startups are begun by immigrants, many of whom are motivated to come to the United States in order to get a high-quality education. To be sure, immigration is a contentious issue, but it bears on how the United States is seen around the world and is a source of power now and in the future. Achieving consensus on a way forward is important to ensuring the continuation of a young, skilled population, which is critical for economic vibrancy and economic growth.

- Finding a Middle Path. This strategy has the same nominal objectives as the one pursued since the end of the Cold War: namely, advancing U.S. security, and preserving Americans’ prosperity and freedom. But it adopts very different methods to achieve these ends. It proposes finding a middle path between post-Cold War primacy and raise-the-drawbridge isolationism. It aims to close the gap between the internationalists and nationalists, solidifying a consensus on protecting vital U.S. interests.

The stay-the-course advocates, in continuing to pursue a confrontational strategy underpinned by the use of force or coercion and the presumption of U.S. military primacy, ignore the risk of feeding the populists’ case for U.S. global disengagement. Trumpian populism gained traction, in part, because of the growing disaffection with the exorbitant costs of America’s seemingly interminable conflicts and owing to a sense that U.S. allies and partners were not bearing their fair share.

American policymakers, and U.S. foreign policy generally, should exert leadership more effectively, through instruments that have served American interests in the past. Certainly, U.S. military muscle was important for deterrence during the Cold War, for example. The true test of U.S. power, however, was its ability to project a superior way of life to that on offer by the Soviets and thereby bring the struggle between capitalism and communism to a peaceful end. The United States benefited greatly from not having to fight a war with the likelihood of heavy casualties and extensive physical devastation.

In recent years, U.S. foreign policy has struggled to set priorities or reconsider goals. Its defenders are often dismissive of the attempt to do so. But a failure to choose risks catastrophe — a decisive and irreparable turn away from global engagement at home and an increased likelihood of major conflict abroad. A credible and sustainable grand strategy must align means and ends. The United States can do more, and more effectively, by prioritizing U.S. strategic objectives, shifting responsibilities to allies and partners, and re-balancing away from military solutions in favor of diplomacy and the more effective use of economic power.

A New Domestic and Global Context Demands New Strategic Objectives

The United States has a long history of successfully adapting its grand strategies to achieve its core foreign policy goals of security, prosperity, and freedom for the American people — and always under changing domestic and international circumstances. The United States lacked, for example, substantial military capacity for much of its history but was highly imaginative in using its available means — mainly diplomacy — to punch above its weight in the global arena. Today, the United States possesses a vast and mighty military, but policymakers have allowed diplomatic tools to atrophy. Meanwhile, despite massive Pentagon spending, the U.S. military has struggled over the last quarter century to bring conflicts to a favorable end.

Strategic objectives have also shifted with the times. Today’s world little resembles even the period at the end of the Cold War, let alone 1945 when U.S. economic power was at its height. From the post-World War II bipolarity of a world divided between the United States and the Soviet Union to the post-Cold War unipolarity in which the United States seemed nearly omnipotent, the world has become multipolar.1Emma Ashford and Evan Cooper call our current era one of “unbalanced multipolarity” in which power is diffused away from a few superpowers to many different middle powers. See “Assumption Testing: Multipolarity Is More Dangerous than Bipolarity for the United States,” Stimson Center, October 2, 2023, https://www.stimson.org/2023/assumption-testing-multipolarity-is-more-dangerous-than-bipolarity-for-the-united-states/. No single state dominates the planet, and even nonstate actors are assuming some of the roles formerly reserved for nation-states. China’s economy might not surpass the U.S. economy in market value in this decade — or ever. But behind China is a rapidly rising India, and, over a longer time horizon, Indonesia, Brazil, South Africa, and Nigeria. Meanwhile, a wide array of middle powers, including many wealthy and stable U.S. allies like France, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom are playing vital regional — and in some cases global — roles.2See Arta Moeni, Christopher Mott, Zachary Paikin, and David Polansky, Middle Powers in the Multipolar World (The Institute for Peace and Diplomacy, March 2022), https://peacediplomacy.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Middle-Powers-in-the-Multipolar-World.pdf.

Russia’s brutal war of aggression against Ukraine has the potential to transform Europe’s approach to its own security, as well as to the United States. This process was already in train before February 2022. Although Europe lags behind the United States in military capabilities, the EU functions as a unitary actor on issues such as trade, economic competition, and technology regulation and increasingly defies or resists U.S. pressure to conform, including, for example, with respect to trade with China.

This is indicative of a broader trend. For the first time in modern history, international relations have become democratized with many non-Western countries taking on more responsibilities in their respective regions — and globally. Many of these rising states share some but not all Western values. Most wish to have good relations with more than just one major power.

Once again, the United States needs to adapt its strategy to a different geopolitical context. With the rise of other non-Western powers, U.S. dominance is no longer widely accepted. Moreover, while the United States aimed to maintain its dominant global position after the end of the Cold War, what the political scientist Samuel Huntington called “primacy,” it was never obvious that doing so was necessary to defend core U.S. interests.3On U.S. objectives for the post-Cold War world, see Patrick E. Tyler, “U.S. Strategy Plan Calls for Insuring [sic] No Rivals Develop,” New York Times, March 8, 1992. See also “Excerpts from Pentagon’s Plan: ‘Prevent the Re-Emergence of a New Rival,’” New York Times, March 8, 1992; on the debate over U.S. strategy in that era, see Samuel Huntington, “Why International Primacy Matters,” International Security 17:4 (Spring 1993); and Robert Jervis, “International Primacy: Is the Game Worth the Candle?” International Security 17:4 (Spring 1993). On different grand strategies, see Barry R. Posen and Andrew L. Ross, “Competing Visions for US Grand Strategy.” International Security 21, no. 3 (1996): 5-53. More to the point, even if primacy was achievable immediately following the end of the Cold War, it certainly is not in 2024, when the U.S. share of global power is declining and that of other countries is rising.4Ashford and Cooper, “Assumption Testing: Multipolarity.”

Advocates of primacy struggle to set priorities or reconsider goals — and are often dismissive of the attempt to do so.5See, for example, Robert Kagan, “Superpowers Don’t Get to Retire: What Our Tired Country Still Owes the World,” New Republic, May 26, 2014; Thomas Donnelly, “Great Powers Don’t Pivot,” in Jacob Cohn, Ryan Boone, and Thomas Mahnken, eds., How Much Is Enough? Alternative Defense Strategies (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2016); and Hal Brands and Eric Edelman, Avoiding a Strategy of Bluff: The Crisis of American Military Primacy (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2017). But ignoring obvious global trends risks causing a catastrophe. History is littered with examples of empires that crashed because of overreach. It would be evidence of enormous hubris if Americans believed the United States was immune to the forces that have brought down other great powers. Renewal, not a stubborn commitment to a strategy from an earlier era, is key if the United States wants to remain a prime mover in the global system. Common sense demands humility and a willingness to take others’ interests seriously. It is a mistake to assume that every actor that does not accept U.S. hegemonic leadership is an enemy that should be put in its place. For most of its history, the United States thrived in a world that it did not dominate.

In making primacy a God-given right, and a goal that should and must be achieved and maintained at all costs, U.S. officials are setting themselves up for eventual failure. Strategy documents published since the end of the Cold War tend to assume that the United States can and must maintain its dominant position in all key regions.6See, especially, excerpts from the draft Defense Planning Guidance of 1992 in Tyler, “U.S. Strategy Plan Calls for Insuring No Rivals Develop.” Other examples include George W. Bush, The National Security Strategy of the United States of America, September 2002, https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/nsc/nss/2002/; and The Department of Defense, Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America: Sharpening the American Military’s Competitive Edge, January 2018, https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2018-National-Defense-Strategy-Summary.pdf. Neither of these assumptions is true. The United States will undoubtedly remain a great power — probably even the first among equals in many areas — but the emergence of many other capable actors, what journalist Fareed Zakaria has called “the rise of the rest,” requires a different approach than what has been employed for most of the last three decades.

The United States will remain a great power, but the emergence of many other capable actors requires a new approach to U.S. global engagement.

Nevertheless, the impulse to stay the course — or even double down on primacy — remains strong. Russia’s brutal war of aggression against Ukraine has prompted calls for a return to the US unipolarity that existed after the collapse of the Soviet Union. What is at stake, primacy advocates say, is nothing less than preserving the post-World War II global order, which Russia’s war threatens to upend. If Russia is not severely punished, China might be encouraged to think that an invasion of Taiwan would be worth the costs and risks.7See, for example, Maura Reynold, “‘We’ll Be at Each Others’ Throats’: Fiona Hill on What Happens If Putin Wins,” Politico Magazine, December 12, 2023; and Anne Applebaum, “The Brutal Alternate World in Which the U.S. Abandoned Ukraine,” The Atlantic, December 2022, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/12/zelensky-congress-speech-us-ukraine-support/672547/. The whole world is watching, and Americans have no choice but to step into the breach, help Ukraine to defeat Russia, and deter China. “In the absence of American leadership,” writes the Brookings Institution’s Robert Kagan, the world will trend inexorably toward “dictatorship and continual great-power conflict.”8Robert Kagan, “A Free World, If You Can Keep It: Ukraine and American Interests,” Foreign Affairs 102, no. 1 (2023): 39–53.

President Biden’s National Security Strategy, released in October 2022, reflects these sentiments, asserting that “the need for American leadership is as great as it has ever been.” In his letter introducing the strategy, Biden committed America to a wildly ambitious agenda to “support every country, regardless of size or strength, in exercising the freedom to make choices that serve their interests.”9Joseph R. Biden, National Security Strategy of the United States of America, The White House, 2022, ii. In an Oval Office address to the nation on October 19, 2023, in which he made the case for additional aid to Ukraine and Israel, Biden asserted, “America is a beacon to the world, still” and “the indispensable nation. . . . And there is nothing, nothing beyond our capacity.”10No“Full Transcript: Biden’s Speech on Israel-Hamas and Russia-Ukraine Wars,” New York Times, October 19, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/19/us/politics/transcript-biden-speech-israel-ukraine.html.

For the United States to become the type of global leader that seeks consensus and compromise, and that does not presume to set the terms for others to follow, will clearly require a radical change in mindset. But few Americans appreciate how flexible U.S. foreign policy strategy and tactics have been, even if the goals have remained the same. Most have never known a world in which the United States was not the clear-cut leader and still revel in the United States’ stupendous achievements in defeating fascism and communism. To the extent that U.S. foreign policy has changed during the last 50 years, it has tended to become more, rather than less, ambitious.11There have been occasional course corrections in the opposite direction, including the post-Vietnam Nixon Doctrine. See, for example, Eugene Gholz, “The Nixon Doctrine in the 21st Century,” World Politics Review, July 22, 2009, https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/the-nixon-doctrine-in-the-21st-century/.

This strategy is built on the understanding that the United States, along with the rest of the world, has been in constant flux. In designing a strategy, U.S. policymakers should embrace that change and welcome contributions to global peace and security from many capable actors, even if those actors are not taking direction from Washington, DC. In short, U.S. grand strategy should be adapted to a current and future world, not an idealized past.

Strategists should first examine U.S. internal priorities and then assess the evolving global environment. Without a strong domestic foundation, any foreign policy will fail. This strategy paper highlights the constraints and opportunities for the United States while considering different means and ways to ensure the essential goals of U.S. foreign policy can be met.

The Constraints on US Power

This strategy begins with a careful look at constraints, the heaviest of which is the domestic political context and how that affects the United States’ ability to craft a credible and consistent foreign policy that advances the interests of the American people.

To be sure, this is not a new problem. The idea that politics in the United States stops at the water’s edge is mostly a myth. But partisanship and severe polarization have derailed nearly every recent attempt to reform U.S. domestic policy, from immigration to the debt. Foreign policy is hardly immune to these pressures. Elected officials will struggle to find common ground.

For example, drawing on results from its 2023 Survey of Public Opinion on Foreign Policy, the Chicago Council reported that Democrats and Republicans have different foreign policy priorities and different ideas about the best ways to achieve their respective goals. According to the Chicago Council’s polling, “Republicans (82 percent) are far more likely than Democrats (49 percent) or Independents (55 percent) to emphasize military strength,” and six out of ten Republicans would “prioritize the United States being a leader in manufacturing (62 percent)” versus just 44 percent of Independents and 41 percent of Democrats who agree.12Note: Dina Smeltz, Karl Friedhoff, Craig Kafura, and Lama El

Baz, 2023 Survey of Public Opinion on US Foreign Policy, Chicago Council on Global Affairs, October 4, 2023, https://globalaffairs.org/research/public-opinion-survey/2023-survey-public-opinion-us-foreign-policy.

Among Democrats, on the other hand, nearly eight in ten would “prioritize combating climate change (79 percent), [and] human rights (78 percent)” and Democrats, “are also distinctly more likely to say that it is very important for the United States to be a world leader in humanitarian assistance (56 percent).” Only 28 percent of Republicans agree.13Smeltz, et al, 2023 Survey of Public Opinion.

With respect to the nature of America’s global role, the Chicago Council notes that 57 percent of all Americans prefer that the United States “take an active part in world affairs” while over four in ten (42 percent) “say it would be best to stay out.” The result, the Council explained, “continues a steady decline in support for international engagement in recent years and is among one of the lowest levels of support recorded in the 49-year history of the Chicago Council Survey.”14Dina Smeltz and Craig Kafura, “Americans Grow Less Enthusiastic about Active US Engagement Abroad,” Chicago Council on Global Affairs, October 12, 2023, https://globalaffairs.org/research/public-opinion-survey/americans-grow-less-enthusiastic-about-active-us-engagement-abroad. An Associated Press-National Opinion Research Center (AP/NORC) poll taken in November 2023 found similar results: 45 percent of all respondents wanted the United States to take “a less active role in solving the world’s problems,” whereas fewer than one in five (18 percent) would have the United States take “a more active role.”15The November 2023 AP-NORC Center Poll, https://apnorc.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Topline-Nov-2023.pdf.

The perception of a decisive turn against global engagement might derive from how different Americans interpret the phrase “an active role.” In fact, many Americans agree that the United States should engage with the rest of the world — but not assume most of the burdens of managing it. Republicans and some Independents are particularly concerned about collective security. Although “a plurality of Americans (42 percent) want the United States to maintain its level of engagement in international organizations on issues of collective security,” according to a poll taken by the Eurasia Group Foundation (EGF), 34 percent of Republicans and 37 percent of Independents favor less engagement; 37 percent of Democrats favor more.16Mark Hannah, Lucas Robinson, and Zuri Linetsky, “Order and Disorder: Views of US Foreign Policy in a Fragmented World,” Eurasia Group Foundation, October 2023, https://egfound.org/2023/10/vox-populi-order-and-disorder/. This was more starkly highlighted in the Chicago Council’s latest polls. “Republicans, in particular,” the Council noted, “have grown more doubtful of the value of continued US engagement overseas. For the first time in nearly 50 years. . . . a majority of Republicans (53 percent) think the United States should stay out of world affairs rather than play an active part.”17Smeltz, et al, 2023 Survey of Public Opinion on US Foreign Policy.

Lackluster Support for Primacy

These findings are particularly pertinent to the role of the military in U.S. foreign policy. For decades, U.S. foreign policy elites have often viewed the use of force and coercion as the sine qua non of America’s influence. Foreign policy pundits have been most critical of U.S. presidents when they have been unwilling to use force. This elite agreement extends to funding the military. Passing large Pentagon budgets is the one thing on which Republicans and Democrats seem to agree. Even opponents of more Pentagon spending admit there is not much debate on the matter — or, when there is, they lose. “That sets the tone for more, more, more for the military,” explained Rep. John Garamendi (D-CA), a member of the House Armed Services Committee.18Connor O’Brien, “‘There was almost no debate’: How Dems’ defense spending spree went from shocker to snoozer,” Politico, July 26, 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/2022/07/26/democrats-defense-spending-military-00048041. In this environment on Capitol Hill and throughout Washington, DC, the view prevails that U.S. military dominance must be maintained in order for the United States to continue to be safe and prosperous at home and a leader globally.

Many Americans beyond the Beltway are increasingly skeptical of this claim, however. A mere 16 percent believe that the United States should spend more on its military, while 34 percent favor cutting the Pentagon’s budget. For the latter group, the top rationale for favoring less defense spending is the desire to see those funds reallocated to “domestic priorities.” And the prospects for mobilizing public support for considerably higher Pentagon budgets in the future are particularly dim. Americans aged 18-29 are nearly twice as likely to support cutting military spending as those over 65 (43 percent to 23 percent).19Hannah, et al, “Order and Disorder.”

The prospects for mobilizing public support for considerably higher Pentagon budgets in the future are particularly dim.

As expected, party affiliation matters, too. Democrats and Republicans sharply disagree over the wisdom or folly of higher military spending, and whether we use it too much, or too little. “Twice as many Independents and Democrats support a decrease in the defense budget as an increase,” EGF reported in October 2023, whereas “Republicans are about evenly split” between wanting to send more or less money to the Pentagon.20Ibid.

Partisan differences are also revealed in the single largest foreign policy expenditure in 2022 and 2023: aid to Ukraine. In this case, however, Republicans want to spend less. A poll taken in November 2023, for example, found that 59 percent of Republicans believe that the United States is spending too much on Ukraine aid, whereas nearly half of Democrats said that Ukraine is receiving the right amount. Overall, only 14 percent of respondents thought that the United States is providing too little support to Ukraine.21“Almost half of Americans think the U.S. is spending too much on Ukraine aid, AP-NORC poll says,” PBS NewsHour, November 22, 2023, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/almost-half-of-americans-think-u-s-spending-too-much-on-ukraine-aid-ap-norc-poll-says.

Supporters of an ambitious U.S. foreign policy, and the costly forward-deployed military forces necessary to execute such a strategy, therefore, are sailing into strong headwinds. They believe that the United States must spend far more on the military than it does today — and are confident that the country can do so without sacrificing necessary investments at home or threatening the overall health of the U.S. economy.22See, for example, Kori Schake, “America Must Spend More on Defense,” Foreign

Affairs, April 5, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2022-04-05/america-must-spend-more-defense. Senator Roger Wicker called for spending at least 5 percent of GDP on the U.S.

military, “A National-Defense Renaissance,” National Review, August 11, 2022, https://www.nationalreview.com/2022/08/a-national-defense-renaissance/, which would amount to about $1.25 trillion in 2023. Former Trump advisor Matthew Pottinger argues this is not nearly enough. “What we have to do is double our defense spending immediately,” he told the Wall Street Journal, which would

bring the total to over $1.6 trillion. Quoted in Adam O’Neal, “Russia, China and the New Cold War,” Wall Street Journal, March 18, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/russia-china-and-the-new-cold-war-ukraine-xi-putin-bloc-dictators-alliance-invasion-11647623768.

At times, the Biden administration seems to agree, calling for higher military spending even as it also plans to spend hundreds of billions of dollars on everything from physical infrastructure to green energy.

The United States has certainly spent more on its military as a share of its economy in the past. Whereas military spending constituted the lion’s share of U.S. federal government expenditures before the Great Society programs of the 1960s, it comprises less than 20 percent of all such spending today. That also means, however, that any additional increment of Pentagon spending must now cut into broadly popular domestic programs — or be offset by higher revenues. Neither seems likely.

Persistent Deficits and Looming Debt

Of course, the United States could just go deeper into debt. That, too, carries risks. During the Cold War era, U.S. military spending to contain and deter the Soviet Union was mostly paid for by current taxes. Large and persistent federal budget deficits were rare, and total public debt as a percentage of GDP averaged 37.6 percent of GDP between 1970 and 1990. In contrast, the average debt-to-GDP since the second quarter of 2008 is 98.3 percent and has hovered at or above 100 percent of GDP since 2012. And the situation has mostly gotten worse in the last few years. In the last three quarters of 2022, for example, the U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio averaged 119.2 percent, and although the first quarter of 2023 saw a decrease to 117.3 percent, the following two quarters saw the increase return with 119.5 percent and 120.0 percent, respectively.23Data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/gfdegdq188S.

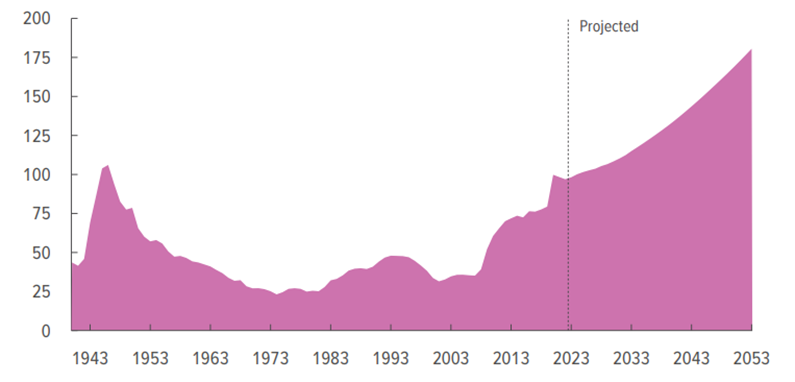

U.S. debt levels will soon rival those at the end of World War II and over the longer term will reach unprecedented levels absent increased revenues (see Figure 1). In August 2023, the Congressional Budget Office reported that the federal budget deficit in the first 10 months of the fiscal year was $1.6 trillion, more than twice the shortfall from the same 10-month period in the previous year.24“Monthly Budget Review: July 2023”, Congressional Budget Office, August 8, 2023, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/59377.

The true scale and significance of the U.S. fiscal imbalance remains hotly contested. Pro-spending economists once pointed to low inflation and low-interest rates to refute the claim that debt levels are unsustainable. But inflation worries now dominate public perceptions of the state of the U.S. economy. In a bid to tame rising prices, the Federal Reserve hiked interest rates seven times in 2022 and four times in 2023; the Federal Funds Rate as of this writing is as high as 5.5 percent, its highest level in 17 years. Inflation has cooled, but after the Kansas City Federal Reserve Bank’s annual Economic Policy Symposium in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, in August 2023, Reuters reported, “Most officials do think the economy will slow, as tight policy and stringent credit are more fully felt and pandemic-era savings are spent down.”25Howard Schneider, Ann Saphir, and Balazs Koranyi, “Analysis: U.S. growth, a puzzle to policymakers, could pose global risks,” Reuters, August 27, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/markets/us/us-growth-puzzle-policymakers-could-pose-global-risks-2023-08-27/.

Figure 1 – Federal debt held by the public (percentage of GDP)

Source: Congressional Budget Office, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2023-06/59014-LTBO.pdf

A rising current account deficit, increased protectionism, and a strong dollar could cause a crisis for those developed countries that have borrowed in dollars. The risk is even more serious for Washington if the United States is seen as printing its currency indiscriminately. Such a perception, coupled with the United States’ accumulating high debt, might eventually sour investors on the dollar. The decision by the rating agency Fitch to downgrade U.S. debt from AAA to AA+, the first such downgrade since 2011, is a worrisome sign of investors’ anxiety.26”Fitch Downgrades the United States’ Long-Term Ratings to ‘AA+’ from ‘AAA’; Outlook Stable,” FitchRatings, August 1, 2023, https://www.fitchratings.com/research/sovereigns/fitch-downgrades-united-states-long-term-ratings-to-aa-from-aaa-outlook-stable-01-08-2023 27 Nicole Goodkind, “America’s credit rating got downgraded again. Here’s what happened the last time,” CNN Business, August 2, 2023, https://www.cnn.com/2023/08/02/investing/premarket-stocks-trading/index.html.

The U.S. federal government’s deficit spending is enabled, in part, by the willingness of foreign bondholders to buy up this debt. Moreover, a leading purchaser of U.S. debt has been China — the very nation that much of this additional spending is aimed at thwarting. The entity that former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton once called “America’s banker” is unlikely to gladly finance a massive increase in U.S. military spending if relations continue to worsen and the risk of conflict grows more acute. And, indeed, China’s purchases of U.S. debt have fallen dramatically in the past decade.28 China’s holdings of U.S. Treasury Securities peaked at $1.317 trillion in November 2013 but had fallen to $778.1 billion by September 2023. Data from “Table 3D: Treasury Securities Held by Foreign Residents” and “Table 5: Major Foreign Holders of Treasury Securities” at “Securities (B): Portfolio Holdings of U.S. and Foreign Securities,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, https://home.treasury.gov/data/treasury-international-capital-tic-system-home-page/tic-forms-instructions/securities-b-portfolio-holdings-of-us-and-foreign-securities. A rational strategy would assume that Beijing will not, to paraphrase a famous dictum, help Washington to buy the rope with which it aims to hang China.

The Declining Utility of US Military Power

Even if U.S. debt remains attractive to foreign buyers, thus allowing for massive increases in Pentagon spending, this strategy assumes that the United States’ ability to maintain a decisive military advantage over any and all possible rivals will still attenuate. Attempting to restore this decisive advantage would almost certainly fail.

Meanwhile, most Americans believe in U.S. international engagement, but they prefer that the United States share the responsibilities and burdens of global leadership with other states. A Gallup poll taken in February 2023 found that only one in five Americans wants the United States to “take the leading role in world affairs,” while 45 percent favor “a major role but not the leading role.” Taken together, the percentage of Americans favoring a leading or major U.S. role has been mostly falling for the last two decades, down from a high of 79 percent in 2003.29Jeffrey M. Jones, “Fewer Americans

Want U.S. Taking Major Role in World Affairs,” Gallup, March 3, 2023, https://news.gallup.com/poll/471350/fewer-americans-taking-major-role-world-affairs.aspx.

This strategy takes account of these facts, recognizing that there is little public support for attempting to dominate the planet militarily, but there might be support for continued active global engagement. Absent a major and imminent threat to the U.S. homeland, however, Americans simply will not tolerate the levels of spending and taxes necessary for deterring all malign actors in all major regions simultaneously. Yet, that is the assumption upon which most strategies are constructed today.

Another assumption guiding this strategy pertains to the technological trends that privilege defense over offense. These very technologies have made it difficult for a military superpower like the United States to decisively defeat even small and weak adversaries, from Saddam Hussein loyalists in Iraq to the Taliban in Afghanistan. More recently, these technologies have enabled an outmanned and outgunned Ukraine to thwart Russia’s war aims. A strategic environment characterized by advanced sensor networks, robotics, and artificial intelligence (AI), as well as miniaturized explosives, greatly complicates the ability of America’s exquisite military platforms to penetrate and conduct offensive operations. However, many of these same technologies allow U.S. allies and partners to maintain a regional balance in their respective areas without relying on U.S. power-projection capabilities many thousands of miles away from the continental United States.30See, for example, Kelly Grieco and Max Bremer, “Assumption Testing: Airpower is inherently offensive,” Assumption #5, Stimson Center, January 25, 2023, https://www.stimson.org/2023/assumption-testing-is-airpower-inherently-offensive/; and T.X. Hammes, “Tactical Defense Becomes Dominant Again,” Joint Forces Quarterly 103 (4th Quarter 2021): 10-17.

Technological trends that privilege defense over offense allow U.S. allies and partners to defend themselves without relying on U.S. power.

Finally, seeing U.S. power only through a static military lens has distorted many analysts’ perceptions of threats. Military tools have failed to protect the United States from a host of dangers. The obsession with jihadist terrorism after 9/11, for example, diverted attention and resources that might have been useful against the COVID-19 pandemic, or to avert the growing damage from climate change. Moreover, adversaries have resorted to asymmetric warfare, such as cyberattacks, against which traditional military tools – from ships and planes to infantry and artillery – are irrelevant.

In short, an overemphasis on great-power military competition could make the United States less protected against all these other threats. The further over-militarization of US foreign policy, effectively ignoring the lessons from two decades of inconclusive wars, would amount to doubling down on failure.

Intense Competition for Resources

Some claim that public opinion on foreign policy is not a reliable guide to what is possible.31On this debate, see, for example, Joshua D. Kertzer and Thomas Zeitzoff, “A Bottom-Up Theory of Public Opinion about Foreign Policy.” American Journal of Political Science 61, no. 3 (2017): 543-58. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26379509. On public attitudes toward the use of force, see Bruce W. Jentleson, “The Pretty Prudent Public: Post Post-Vietnam American Opinion on the Use of Military Force,” International Studies Quarterly 36, no. 1 (1992): 49-73; and Bruce W. Jentleson and Rebecca L. Britton, “Still Pretty Prudent: Post-Cold War American Public Opinion on the Use of Military Force,” The Journal of Conflict Resolution 42, no. 4 (1998): 395-417. Nonetheless, grand strategy should take public sentiment into account — and especially the public’s willingness to expend additional sums to sustain the status quo. As political commentator Walter Lippmann famously advised in 1943, “Foreign policy consists in bringing into balance, with a comfortable surplus of power in reserve, the nation’s commitments and the nation’s power.”32Walter Lippmann, US Foreign Policy, Shield of the Republic (Boston: Little Brown, 1943), 9. When he wrote that, the American people were accustomed to sacrifice and privation. The memory of the Great Depression was still fresh, and the United States was fighting a two-front war against both Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. Millions of American men had been drafted into the military, hundreds of thousands would be killed, and many more would be severely injured. Meanwhile, mobilization at home was upsetting long-established norms. Rationing and wage-and-price controls had become the norm. Millions of American families planted victory gardens. And the top income tax rate was 94 percent. During World War II, there was broad and deep consensus behind what the United States was doing overseas and a willingness to sacrifice to see those two wars to a successful conclusion.

Today, the situation could not be more different. A tiny fraction of Americans have served in the military. Tax rates are low, and political activity is mostly focused on lobbying for more domestic spending, including for countless programs that did not exist in 1943, from Medicare for seniors to student loan forgiveness for the youngest voters. A grand strategy without a durable domestic foundation risks writing checks that the body politic will not cash.

A grand strategy without a durable domestic foundation risks writing checks that the body politic will not cash.

The competition for resources between foreign and domestic priorities is not always so stark. After World War II, living standards for a wide swathe of Americans rose, even as the U.S. military maintained a global presence unlike anything previously attempted. This was possible, in part, because the U.S. economy grew at an average annual rate of 5 percent in the 1960s. In contrast, in the 30 years since the end of the Cold War, growth has averaged barely 3 percent and a meager 2.3 percent since the financial crisis of 2008-2009 (see Figure 2). And although U.S. GDP has more than doubled since 1999, median household income, after adjusting for inflation, has grown by just 6.6 percent.33In constant, 2021 dollars, median household income in the United States stood at $70,784 in 2021, as compared with $66,385 in 1999. Notably, incomes were mostly stagnant during the 2000s and well into the 2010s; median income remained under its 1999 peak until 2016 ($66,657). See Table H-5. “Race and Hispanic Origin of Householder–Households by Median and Mean Income: 1967 to 2021”, at https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-income-households.html. The Congressional Budget Office projects that annual US economic growth will average 1.8 percent between 2023 and 2033.34Molly Dahl, “CBO’s Analysis of the Long-Term Budgetary Outlook,” Congressional Budget Office, November 16, 2023), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2023-11/59724.pdf.

To be fair, no one can know for sure how the U.S. economy will perform in 2024, let alone 2034 or 2054. But no prudent foreign policy can be built on an assumption of unlimited resources. The U.S. economy is still the largest in the world by most measures, but growth has slowed, and the already intense debates over how to allocate scarce taxpayer dollars will only increase. In particular, given urgent domestic priorities, additional resources are unlikely to be made available for much higher military spending. This, too, should be a reason for a cautious U.S. strategy that does not rely primarily on the use of force and coercion. Even if the U.S. economy grows faster than current projections expect it to, increased government revenues from the boosted growth could well end up being reinvested in greater domestic spending, including in a stronger safety net. Medicare and Social Security face bankruptcy in the early 2030s absent an infusion of additional revenues and, for many in Congress on both sides of the aisle, maintaining these programs is as vital as a strong defense.

Either way, intergenerational tension is likely. Retirees or those nearing retirement will clamor to retain the benefits they were promised, even as the relatively less-affluent young and middle-aged populations struggle to adapt to a global economy rushing headlong toward digitalization. Inequality has been and remains a debilitating worry, particularly the broadly held sense by various groups that “the deck is stacked against them.” Studies have shown that where individuals lives and their parents’ incomes are more critical to success than their own abilities.35In a YouGov survey taken in 2020, fewer than half of Millennials surveyed (46 percent) believed the American dream was attainable. Jamie Ballard, “In 2020, do people see the American Dream as attainable?” YouGov America, July 18, 2020, https://today.yougov.com/topics/politics/articles-reports/2020/07/18/american-dream-attainable-poll-survey-data.

A highly skilled workforce is needed more than ever, and American society is becoming stratified according to differing levels of educational achievement. Even more, in the face of rapid technological change, many young people doubt they have the skills to compete. Their parents agree. A survey in March 2023 found that nearly four in five Americans (78 percent) were not confident that life for their children’s generation would be better than their own.36Janet Adamy, “Most Americans Doubt Their Children Will Be Better Off, WSJ-NORC Poll Finds,” Wall Street Journal, March 24, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/articles/most-americans-doubt-their-children-will-be-better-off-wsj-norc-poll-finds-35500ba8. Americans who lack self-confidence about the future, and for whom the American dream seems out of reach, will not support an ambitious foreign policy that spends vast sums of money half a world away.

Americans who lack self-confidence about the future, and for whom the American dream seems out of reach, will not support an ambitious foreign policy that spends vast sums of money half a world away.

Unsurprisingly, given the country’s lackluster economic prospects, Americans’ sense of their own well-being has taken a hit. But it is not just about money; people also worry about their lives. Although much of the rest of the world started from a lower baseline, life expectancy has increased elsewhere, but peaked for Americans in 2014. This has occurred despite Americans spending more on healthcare relative to other advanced economies.37Life expectancy at birth in the United States was 78.9 years in 2014; it was 76.4 years in 2021, the last year for which data is available. By contrast, average life expectancy among comparable countries (Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, and the U.K.) was 82.2 in 2014, and now stands at 82.3, and has nearly erased a slight decline in 2020 from COVID-19. See Shameek Rakshit, Matthew McGough, Krutika Amin, and Cynthia Cox, “How Does U.S. Life Expectancy Compare to Other Countries,” Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker, October 12, 2023, https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/u-s-life-expectancy-compare-countries/. Regarding life expectancy as compared with health care spending, see Krutika Amin, “The U.S. Has the Lowest Life Expectancy Among Large, Wealthy Countries While Far Outspending Them on Health Care,” Kaiser Family Foundation, December 9, 2022, https://www.kff.org/other/slide/the-u-s-has-the-lowest-life-expectancy-among-large-wealthy-countries-while-far-outspending-them-on-health-care/.

U.S. health challenges and declining life expectancy pre-dated COVID-19. Important research by economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton detailed how “mortality rates from drugs, alcohol, and suicide have been rising” for more than two decades.38Anne Case and Angus Deaton, Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020), 80. A subsequent study conducted in 2022 confirmed that there has been “a progressive increase in deaths attributable to suicide, drug overdose, and alcohol-related liver disease in the USA in the last two decades.” These deaths “have sent USA life expectancy falling for several years, making it a public health concern.”39Elisabet Beseran, et al, “Deaths of Despair: A Scoping Review on the Social Determinants of Drug Overdose, Alcohol-Related Liver Disease and Suicide,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 29;19(19)(September 2022):12395. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191912395. Indeed, one could say it is a national security concern because such “deaths of despair” now claim far more American lives each year than all U.S. wars since Vietnam. A record number of people — at least 49,499 — died by suicide in the United States in 2022.40Deidre McPhillips, “Suicide Deaths Reached a Record High in the US in 2022, Provisional Data Shows,” CNN, August 10, 2023, https://www.cnn.com/2023/08/10/health/suicide-deaths-record-high-2022/index.html. Another 109,680 died from drug overdoses, also a record.41Brian Mann, “US Drug Overdose Deaths Hit a Record in 2022 as Some States See a Big Surge,” NPR, May 18, 2023, https://www.npr.org/2023/05/18/1176830906/overdose-death-2022-record.

Fix the Homefront

In short, untangling domestic problems is not a distraction from U.S. objectives abroad: It is a necessary precondition to any credible U.S. grand strategy. It also presents an opportunity. The past few years have been hard on U.S. standing in others’ eyes. The publics in key U.S. allied countries no longer believe that the United States is a full democracy. A solid majority of Americans agree; they do not see the U.S. political system as a good model for others to follow.42See Bruce Stokes, “The Decline of the City Upon a Hill: As American Democracy Loses Its Shine, American Power Suffers,” Foreign Affairs, October 17, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/decline-city-upon-hill.

Many Americans are aware of these challenges, though they disagree about their causes. They sense that the country needs a course correction, but they disagree about how to execute one. This strategy paper does not pretend to have the answers, but it does call upon policymakers to dedicate time, attention, and resources — which might otherwise have been directed abroad — to addressing the American people’s most urgent concerns here at home.

It is critically important to build an attractive model if others abroad are to be persuaded to follow the United States. Should Americans want others to become democracies, for example, then the United States must become a democracy worth emulating. Doing so will require a concerted effort on the part of the leaders of both major political parties to find common ground and reach compromises on contentious issues — from voting rights to immigration to spending and taxes. Of course, forging a new political consensus cannot occur overnight. Regrettably, many policymakers have a limited understanding of the importance of having a vibrant and inclusive democracy for U.S. standing and competitiveness in the world.

The great American strategist George Kennan understood this well. He once said that the United States would triumph over the Soviet Union in the Cold War as long as America was seen as “coping successfully with the problem of its internal life.”43X [George Kennan], "The Sources of Soviet Conduct," Foreign Affairs 25, no.4 (1947): 581. When Kennan wrote that, the American lifestyle was unquestionably aspired by many around the world. Although that may still be true for some, others are unconvinced. The United States could do more to earn back the world’s respect. Doing so begins with demonstrating a capacity for solving problems at home and taking seriously the interests of those abroad.44Fifty percent of respondents to a Pew Research poll taken in Spring 2023 said that the United States did not “take into account the interests of countries like theirs.” “International Views of Biden and U.S. Largely Positive,” Pew Research Center, June 27, 2023, https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2023/06/27/international-views-of-biden-and-u-s-largely-positive/.

To be sure, the United States has many strengths, including the world’s largest and most dynamic economy, a vibrant private sector, and a higher education system that remains the envy of the world. But few doubt that we can do better. Tapping into the United States’ unique advantages will most likely require thoroughgoing political reforms.

Based on the experience of the last decade, it seems unwise to assume that this political breakthrough is in the offing. The more likely scenarios involve continued relative U.S. decline, which will, in turn, leave the United States progressively less able to obtain what it wants through economic or diplomatic pressure, and with a military instrument that struggles to achieve its objectives. This compels the United States and leading strategists to make difficult choices, work with allies and partners, and be willing to compromise where U.S. vital interests are not at stake.

Rapid Change in the Global Balance of Forces

So far, this strategy paper has mostly focused on how domestic political and economic challenges complicate U.S. global ambitions. But external constraints exist as well. The most important geopolitical development during the last three decades has been the rise of China. In the early post-Cold War era, the reigning assumption was that China would integrate into a US-led global order, slowly becoming a “responsible stakeholder.” But today, Deng Xiaoping’s guidance to other Chinese leaders to “Keep a low profile and bide our time” is a distant, fading memory. The shift likely began in the late 2000s and has accelerated under Xi Jinping. As the 2008 financial crisis unfolded, Beijing became convinced that the United States was in decline. Rising Chinese nationalism spurred aggressive behavior toward China’s neighbors and a desire to see the Middle Kingdom respected in the world. Few Chinese blame themselves for the deterioration in US-China ties: In their eyes, the United States’ sense of its own decline is the root cause of the growing tensions in the bilateral relationship.45Yun Sun, “Current U.S.-China Relations and the Pivot to Asia,” in A US Pivot Away from the Middle East: Fact or Fiction? (Arab Center, 2023), https://arabcenterdc.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/A-US-Pivot-Away-from-the-Middle-East_Fact-or-Fiction.pdf. See also Alastair Iain Johnston, “China in a World of Orders: Rethinking Compliance and Challenge in Beijing's International Relations,” International Security, Vol 44, No. 2 (Fall 2019) 9–60, https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00360.

The U.S. and Chinese economies were closely intertwined in the 1990s, but now a potential mirror effect is operating in the relationship. As the Chinese have grown more insistent that their country be treated as a great power, U.S. foreign policy elites have resisted the suggestion that the United States is in relative decline. In this context, Washington is searching to come up with simple ways to put the “dragon” back in its place, but China is a different animal than the Soviet Union, the last big geopolitical challenger that confronted the United States. For one thing, China, unlike the Soviet Union, is an economic powerhouse with extensive trade relations around the world — including with U.S. partners and allies who are anxious to preserve these mutually beneficial arrangements (see Figures 3 and 4).

China faces many challenges, including a looming demographic crisis and the prospect of slowing growth. Its outdated economic model is pushing the country toward the middle-income trap. It did not recover quickly or well from the COVID-19 pandemic; Beijing’s Zero-COVID policy was a disaster, and its vaccines are less effective than those used in most Western counties. It is sitting atop a massive real estate bubble that could easily precipitate a financial crisis far more serious than that of 2008-2009. A recent Wall Street Journal headline concluded “China’s 40-Year Boom Is Over.”46Lingling Wei and Stella Yifan Xie, “China’s 40-Year Boom Is Over. What Comes Next?” Wall Street Journal, August 20, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/world/china/china-economy-debt-slowdown-recession-622a3be4.

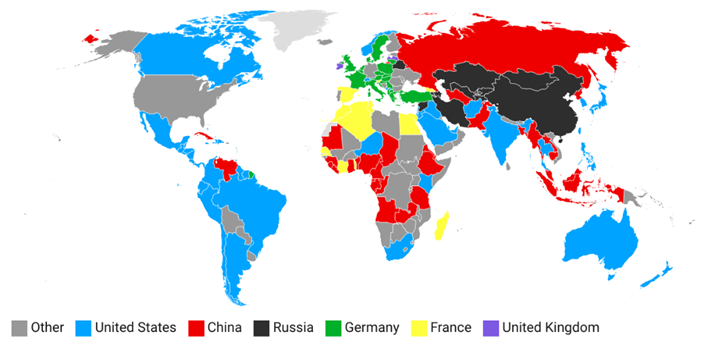

China continues to spend on its military, but the International Institute for Strategic Studies noted “growth in real terms . . . has stalled in the last five years.”47The Military Balance 2023 (London: International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2023), 225. Despite concerns that China is catching up with the United States militarily, it spends about half as much as a share of GDP, and less than a third in real terms.48The United States spent about 3.5 percent of GDP on the military in 2022, as compared with China’s 1.6 percent. In US$, China spent $291.9 billion to the United States’ $876.9 billion. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, SIPRI Military Expenditure Database. The International Institute for Strategic Studies reports U.S. defense expenditures at $766.6 bn to China’s $242.4 bn (or $360 bn by Purchasing Power Parity) in 2022. The Military Balance 2023, 14. See also “The United States Spends More on Defense than the Next 10 Countries Combined,” Peter G. Peterson Foundation, April 23, 2023, https://www.pgpf.org/blog/2023/04/the-united-states-spends-more-on-defense-than-the-next-10-countries-combined. Meanwhile, Beijing is using trade, development assistance, and diplomacy to spread China’s influence, and the focus is increasingly global, not just in East Asia. China, for example, has displaced France and the United Kingdom as the top influencers in many African countries in just the past decade (see Figure 5).

Figure 5 – Top Influencer: 2022

Source: Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures, Formal Bilateral Influence Capacity Index

The dramatic shift in the global balance of power runs deep and wide. In addition to China’s growing influence, the number of middle powers has been increasing, and their interests do not perfectly or automatically align with the two largest economic powers; for many, their top priority is maintaining cordial relations with both the United States and China. Moreover, the growing economic importance of emerging markets and developing countries ensures that the number of middle powers will increase in the future.

It would be a gross miscalculation for Washington to assume that its allies and partners will reflexively follow it in any conflict with China. As the response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has shown, individual countries react differently to global crises, and U.S. pressure to conform in today’s world would be less likely to produce the desired effect than it would have a generation ago. Although China has few formal treaty allies, its trading partners will be highly motivated to avoid courting disfavor with Beijing. These countries are likely to hedge against both Beijing and Washington and seek to maximize their options in the event that the US-China competition turns hot.

History does sometimes repeat or “rhyme” (as Mark Twain said) but no one should wish for another Cold War, which wreaked havoc on much of the world. Trying to “contain” or “decouple” from China would boomerang on U.S. economic prospects. It is unrealistic to expect that variations of the same primacy strategies first implemented decades ago would work in a completely different situation today but will simply require more effort on the part of U.S. leaders. Foreign policy professionals in the United States need to be more creative, developing an original strategy that matches the remedy with reality.

Russia, Ukraine, and the Return of History

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine threatens more than peace in Europe; it has also set back bilateral and multilateral cooperation on many fronts. These are unlikely to be restored as long as Putin rules Russia. But the United States and other countries must prepare for the future; a grand strategy can help the U.S. and its allies and partners to get there. Putin will go away; Russia will not.

Thus, even if constructive relations are difficult or impossible in the near- to medium-term, some measures can and should be taken to ensure continued working-level engagement. The Arctic has become an entirely new arena for military competition and confrontation. The danger of an unintended escalation, or even military action is rising in space and elsewhere. Meanwhile, the increasing range and reduced response time of current and emerging non-nuclear offensive weapons systems and their highly automated command-and-control systems heighten the risks of accidental collisions.

Arms control agreements are becoming harder to maintain; achieving new breakthroughs will be difficult. This is not a recent phenomenon. The George W. Bush administration pulled out of the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in 2001.49James M. Acton, "The U.S. Exit From the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty Has Fueled a New Arms Race," Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, December 13, 2021, https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/12/13/u.s.-exit-from-anti-ballistic-missile-treaty-has-fueled-new-arms-race-pub-85977. The Trump administration withdrew from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) and Open Skies Treaties, as well as the P5+1 nuclear agreement with Iran. These decisions set a string of bad precedents for stemming arms races and limiting nuclear proliferation.

And the prospects for limiting the growth of nuclear arsenals have only worsened since Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. In the ensuing two years, Moscow declared that it would no longer participate in New START. Then, in November 2023, Russia formally withdrew from the Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) treaty. The last remaining arms control agreements of the post-Cold War era are effectively null and void.

Absent concerted efforts, nuclear weapons risk being transformed from a stabilizer, as in the Cold War’s great-power conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union, to asymmetrical “weapons of the poor” to be used against adversaries’ superior conventional forces. This significantly increases the likelihood of their use in local wars. Meanwhile, measures by some established nuclear weapons states, including the United States, to develop low-yield, and thus allegedly more usable weapons, could increase the risk that such weapons will be employed deliberately. President Ronald Reagan’s famous dictum that “a nuclear war cannot be won, and must never be fought,” which was reaffirmed by the five nuclear weapons states in January 2022, now seems in question.50The White House, “Joint Statement of the Leaders of the Five Nuclear-Weapon States on Preventing Nuclear War and Avoiding Arms Races,” January 3, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/01/03/p5-statement-on-preventing-nuclear-war-and-avoiding-arms-races/.

And strategic stability is threatened by more than just numbers of weapons or their changing character. The United States, Russia, China, and other nuclear weapons states should commit to working together to ensure that AI and disruptive cyber operations are never aimed at adversaries’ nuclear arsenals. All parties should recognize their mutual vulnerability to such measures, and that no party would benefit from such attacks.

The Need for Cooperation to Tackle Global Challenges

Although the risk of great-power competition spilling over into outright conflict is the leading concern today, that should not crowd out other foci for U.S. foreign policy.51Bruce W. Jentleson, “Refocusing US Grand Strategy on Pandemic and Environmental Mass Destruction,” Washington Quarterly, 43:3 (2020), 7-29, DOI: 10.1080/0163660X.2020.1813977. The COVID-19 pandemic was an unwelcome reminder that many things other than war can be a threat to the immediate well-being of all. The greatest of these is climate change, which constitutes an existential threat to humanity. Of course, there is no quick fix such as the vaccines that were developed and produced in record time, but ignoring climate change is not an option. The threat is immediate, not in some far-distant future, as many believe.

Prioritizing is an essential part of strategizing. Too often, foreign policy professionals segment the treatment of different threats, often layering one on top of the other, and losing the overall context in the process. U.S. policymakers risk falling into this trap with their increasingly single-minded focus on China. Serious issues connected with China’s behavior deserve U.S. and global attention. Allowing Sino-US differences to get out of hand and crowd out other concerns, however, risks exacerbating the existing upward trend toward conflict, and undercutting needed cooperation on the greatest challenges facing humanity.

The COVID-19 pandemic was an unwelcome reminder that many things other than war can be a threat to the immediate well-being of all.

Setting priorities begins with articulating clear goals. The goals that this strategy aims to achieve are simple and straightforward. The U.S. government’s overarching responsibilities to the American people are protecting their security, prosperity, and freedom. Americans expect their government to protect them from threats, both foreign and domestic. Policy should maximize opportunities for people to provide for themselves and their families. How U.S. grand strategy achieves these first two goals relates to the third: freedom. Policy should afford maximum autonomy to the individual and prevent encroachments on people’s liberties. The first two objectives are typical of most governments throughout history. But measures that would be tolerated, or even welcomed, in nations that afforded their governments far greater control over their citizens’ lives will not work in the United States. Similarly, a national security strategy appropriate to a different country, under different circumstances, will not work for a federal republic of 50 states, spread across a vast swathe of land and seas, but more secure from traditional security threats than most other countries.

Indeed, a tendency to define U.S. national interests too broadly has undermined America’s security in recent years, for example, by drawing the United States into conflicts that it cannot win and need not fight. Anger and resentment at America’s often heavy-handed and overly militarized approach to global engagement have eroded America’s unique advantages as an exemplar of good governance and liberalism and have even generated acts of violence against Americans — including the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Meanwhile, costly and inconclusive wars have sapped Americans’ will and drained the U.S. treasury. Money spent on foreign wars, a growing number of Americans now believe, would have been helpful in dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic, addressing the climate-change crisis, or building out physical or cyberinfrastructure here at home.

That point relates to the second core goal of this strategy — maintaining and expanding prosperity for the widest possible number of Americans. That prosperity is contingent upon access to global markets, but the free movement of goods and services cannot depend upon the power of a single state to facilitate it. Precisely because the global commons is used by all trading nations, all nations must play a critical role in keeping those commons open.

Last, as noted above, this strategy aims to advance U.S. security and prosperity, while also maintaining a commitment to individual liberty and political liberalism. Approaches that transgress or otherwise violate the U.S. Constitution’s limits on state power, or that are inconsistent with free-market principles, will not command broad public support and are likely to fail.

A National Security Strategy that Sets Priorities – Major Elements

It has been evident for some time that U.S. foreign policy has been out of sync with two major trends: the growing disconnect between the American people and policy elites over the cost, and the changing international context of emerging multipolarity. Primacy is no longer attainable and efforts to achieve it are either apt to fail, or else undercut the very basis for a renewed US role on the world stage.

As outlined in the previous section, reformulating U.S. foreign policy should begin with closing the gap with the American people who have shouldered the burden of a particular type of U.S. engagement in the world.52As shown by the U.S. war in Afghanistan, for example, no U.S. commitment is tenable without public support. See C. William Walldorf Jr., “Narratives and War: Explaining the Length and End of U.S. Military Operations in Afghanistan,” International Security; Vol. 47, No. 1 (Summer 2022): 93–138, https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00439 . After years of stagnant incomes in the face of increasing costs for healthcare, education, and other items associated with a middle-class standard of living, strengthening the home front should be the first element of a credible grand strategy.

Second, the United States cannot have a successful foreign policy without making choices. Believing it can return to the halcyon days of the 1990s — when the United States was near the peak of its economic power and facing no competitors — can only lead to attempting to do too much with too little. Even during the Cold War, US policy was not successful in every instance, and officials learned over time to husband the nation’s resources and seek cooperation, not just confrontation, with Soviet Communism.

Finally, U.S. policymakers must understand that so-called “soft power” may be the country’s best and most effective source of influence. Military force is not suited to solving most of the world’s problems. Much of the history written today about the Cold War emphasizes that the United States prevailed due to the appeal of the Western model of individual freedoms and affluence, which the Soviets — with their overreliance on fear and military might — could not equal over time.

This section sketches out the major elements of a much-needed reinvention of U.S. foreign policy.

Make Choices

U.S. National Security Strategies often read like laundry lists of goals without much prioritization. That needs to change. The combination of domestic and international constraints necessitates a clear articulation of US strategic priorities. Even superpowers need to balance ends, ways, and means. Retaining global dominance is not necessary to secure vital U.S. interests, nor is it viable in a multipolar world. Being globally engaged is vital for national interests, and the United States has many instruments — not just its military power — to ensure that it achieves its core national security objectives.

The focused strategy advocated here would first set priorities around vital U.S. interests and, second, identify different ways of achieving those effects at less cost in view of the limited public support for an ambitious foreign policy that draws resources away from domestic needs.

What and How to Prioritize

Although Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine has forestalled dialogue with Moscow, avoiding major-power conflict remains an overarching U.S. interest. Better relations with China should help. China is a major competitor, but not an existential threat to U.S. national security. Despite the growing tensions of the present era, China does not have a track record of conquest. It should not become such a focus as the Soviet Union was for the United States in the Cold War, crowding out all other interests.

Trying to stabilize the relationship with China through more open communications should be a priority for lessening the risk of escalation and open conflict. Examining the United States’ own behavior to avoid provocation is imperative. For example, Taiwan is an emotional, almost existential issue, for mainland China; U.S. policymakers need to keep this in mind as they craft policies to preserve the status quo.53See, for example, Bonnie S. Glaser, Jessica Chen Weiss, and Thomas J. Christenson, “Taiwan and the True Sources of Deterrence: Why America Must Reassure, Not Just Threaten, China,” Foreign Affairs, November 30, 2023.

The combination of domestic and international constraints necessitates a clear articulation of US strategic priorities. Even superpowers need to balance ends, ways, and means.

Putin’s aggression against Ukraine is a reminder of his malign intentions, but Russia’s abysmal performance in the war reveals its weakness. Future Russian leaders will be anxious to avoid repeating Putin’s mistakes. For the United States, a deepening militarized competition with either China or Russia threatens prosperity at home, making it harder, if not impossible, to undertake domestic renewal. Although promoting core democratic values has been an important goal of U.S. policy, such idealism needs to be coupled with realism. Putting democracy promotion, for example, at the core of foreign policy runs the risk of undermining Washington’s ability to find areas of cooperation with other countries that do not share U.S. values.