Peace Dividends of Renewables in Fragile States

The fragile countries where peacekeeping missions are deployed are among those facing the most significant climate vulnerability and lowest electricity access. The absence of resilient infrastructure and reliable energy availability contributes to the challenges that host countries face in building stable political systems and ensuring sustained economic development. Developing integrated strategies that can address the unique challenges of climate vulnerability, state fragility, and energy poverty is critical to the wellbeing of a society and ultimately, the success of a UN Peacekeeping mission. Powering Peace’s own data dashboard, which aggregates relevant data for each country, helps to illustrate how these factors are interconnected.

As an international organization with a presence around the world, the UN has a large carbon footprint. Peacekeeping missions are often deployed in fragile settings with limited energy resources, making them among the largest energy consumers in their host countries. The status quo for most missions today is that electricity is self-generated by on-site diesel generators for the mission’s exclusive use. The installation of renewable energy infrastructure operated by the UN can lay the foundation for sustainable Mission programming, helping the UN achieve their own climate goals. Expanding that energy capacity beyond the UN compound’s fence can lead to enhanced energy access for local communities and support a transformation of their own livelihoods. Increased renewable energy resources can also lower the cost of electricity and eliminate the need for diesel fuel supply chains. In many conflict settings, fuel convoys must pass through numerous checkpoints controlled by conflict actors, a negative side effect of diesel dependency that can exacerbate communal conflict and encourage criminal networks. More renewable energy can lead directly to improved economic opportunities for local economic stakeholders.

Positive Legacies in UN Operations

The UN Secretariat unveiled its first Environment Strategy for Peace Operations in 2017. A core pillar of this strategy is that the “wider impact” of peace operations should “take account of environmental impact” and “increase the extent to which their footprint leaves a positive legacy.” Although not part of the original concept of peacekeeping missions, this new strategy codified positive legacy terminology in UN documents even though there is no formal UN definition of positive legacy. The underlying idea is that missions will foster enduring contributions to peace through policy and infrastructure that will explicitly benefit the host country over time. This strategy is a step toward mainstreaming the concept of long-term positive legacy into mission planning. Missions are encouraged to identify projects and activities that can leave a positive and long-term impact from the presence of peace operations.

Peacekeeping liquidation and asset disposal measures were not developed with an eye towards leaving mission assets in countries after the departure of missions. The UN Financial Regulations and Rules indicate that equipment from liquidating a peace operation can only be considered for disposal by gift or by sale at nominal value to a government if it is not required for any other peace operation, other UN activities funded from assessed contributions, or other UN agencies, international organizations, or NGOs. Thus, there is currently no established procedure or process for leaving behind renewable energy infrastructure, much less developing structures to support its operation and possible expansion beyond the mission to benefit the local community. These regulations and constraints are therefore at odds with the stated intentions of positive legacy.

Some UN missions are already sharing renewable energy technology with local stakeholders through Quick Impact Projects and other small-scale programs. However, unless there is a dedicated effort to extend power generation beyond the fence and eventually hand over energy infrastructure, the missions will not realize the full potential of positive legacy opportunities.

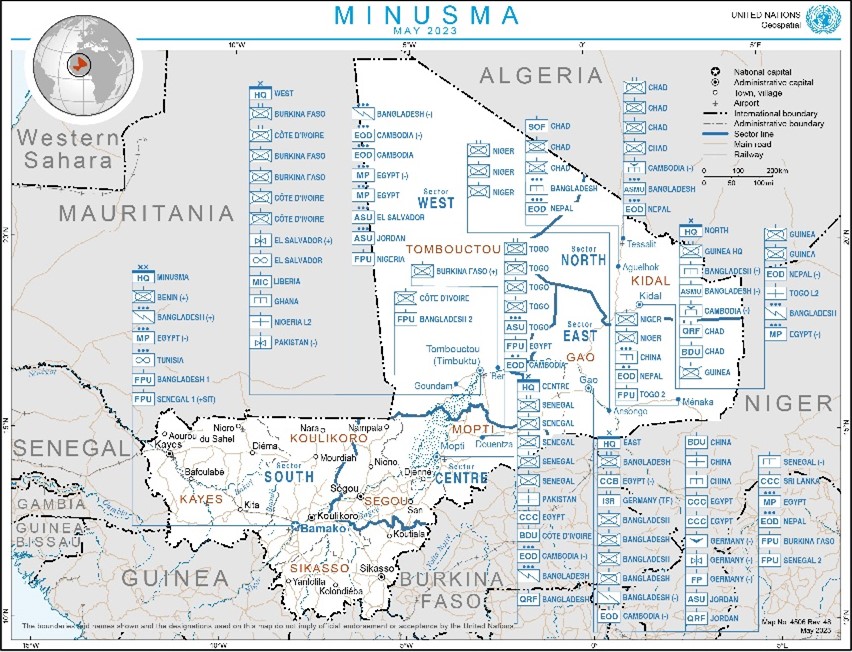

UN Geospatial

Dangers of a MINUSMA Precedent

Following Bamako’s urgent demand in June 2023 to terminate MINUSMA, the UN Security Council promptly passed Resolution 2690 later that month, which formalized the end to MINUSMA operations and established a highly ambitious timeframe for its departure. The standard practice for Transition and Liquidation of mission assets is a phased approach, with a 6-12 month period during which the closure plan can be developed. For MINUSMA, the Council insisted on a complete cessation of operations, transfer of tasks, and withdrawal of personnel by December 31, 2023, so the Mission was required to develop and implement its closure and liquidation plans within a compressed timeline. Despite nascent plans to incorporate renewable energy through various power purchase agreements (PPAs) into operations for specific mission sites, any further consideration of transition planning for MINUSMA was just beginning. Given the absence of a longer-term transition plan, MINUSMA was forced to abandon its ambitions for incorporating long-term renewable energy projects into its operations.

Longstanding expectations for the closure of peace operations are for the Security Council to end the mission only after sufficient progress in the fulfillment of the mandate. However, this model has frayed in recent years; MINUSTAH, MINUJUSTH (both in Haiti), and UNAMID (Darfur) all closed prematurely due to lack of political support within the country or complicated Security Council dynamics. The situation in Mali is a warning sign that the template for an organized, UN-initiated closure – when the country has graduated to a more stable peace – cannot be the default expectation. The case of MINUSMA suggests that more host countries may initiate future transitions, with little warning, on accelerated timelines and short of the stated goals of the UN mission. While this shift will not precipitate the collapse of other UN missions, it may reflect the end of an era for large-scale international peacekeeping in Africa. The status quo is likely to persist, but there seems little appetite for a new multidimensional UN peacekeeping mission in the future; no UN peacekeeping missions have been approved since MINUSCA in 2014. At the same time, an international imperative to address conflict through other multinational or regional forces is likely to remain. Given the uncertain life expectancy of large-scale multidimensional missions, which include peacebuilding, civilian services, and human rights protections in addition to miliary policing, transition planning needs to become a standard feature of a mission’s daily operations to future proof it against a sudden closure.

Building positive legacy into the architecture of existing missions and future iterations of peacebuilding systems can contribute to the Mission’s ongoing success by building host community support for the UN presence and its effectiveness, as well as the international community’s confidence in peacekeeping as a model. Infrastructure projects such as renewable energy can contribute to both the lasting success of the mission as well as providing immediate support and benefits to local communities. These projects also offer a way for an upfront investment in positive legacy, while providing the UN with a clear way to achieve their climate commitments, extend renewable energy access, and bolster community resilience while delivering on the ultimate goal of enduring peace and security.

Opportunities for Positive Legacy Prioritization

The changing landscape of UN peacekeeping — more Special Political missions, fewer personnel, and more targeted mandates – should encourage creative solutions and new ways of thinking for future operations. There are several promising approaches that have already begun to address this shift.

Areas of Progress

The Security Council took an important first step in 2021 to highlight peacekeeping transitions as a central consideration rather than an afterthought when it passed Resolution 2594: the first stand-alone resolution on peacekeeping transitions. The resolution calls for an integrated approach to transitions at the earliest possible stage of a peace operation’s life cycle and reinforces the goal of national ownership in development of sustainable peace. However, the resolution neglects to directly reference infrastructure and environmental considerations that will only become more critical in the coming decades. The Secretary-General’s report pursuant to the Resolution included a section on environmental impact, which outlines the importance of renewable energy in the responsible conclusion of missions. Specific language highlights that clean energy infrastructure “would benefit local communities long after the departure of the mission.” While the Secretariat advocates for environmental concerns in the transition process, only the UNSC has the power to establish legally binding requirements. Sidestepping these mandates will mean missions will lack the tools they need to transition successfully.

Additionally, in 2022 and 2023 each UNSC mandate renewal resolution for the “big five” UN peace operations – Mali, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Central African Republic, South Sudan, and Somalia – directly referenced the Secretariat’s Environmental Strategy, including explicit mention of renewable energy in the context of the mission’s positive legacy. Each mandate “emphasises good stewardship of resources and a positive legacy of the mission, and identifies the goal of expanded renewable energy use in missions to enhance safety and security, save costs, offer efficiencies and benefit the mission.” Guidance from the mandate opens the door for RE prioritization in mission programming; the UN must now walk the walk regarding the design and implementation of projects.

Possibilities for Further Integration

While official UN engagement with positive legacy has gained significant traction in recent years at a conceptual level, real adjustments to the transition process and wider impact of peace operations will require concrete changes. One place to start would be the improvement of the Rules and Regulations of the liquidation process which will require broader support from Member States, as only the General Assembly can approve amendments. The changes should include asset disposal measures related to gift or sale at nominal value from a last resort to standard practice, allowing missions to better use their existing assets as part of the broader positive legacy of missions.

In addition, UN country teams should be involved in the transition process through coordination. Multidimensional missions have supposedly been integrated with country teams for over a decade now, but this has faltered in practice. In the context of UN transitions, the UN needs to take integration more seriously and involve country teams both on peacebuilding tasks but also issues related to infrastructure and energy transition, encompassing the broader UN system.

Looking to other missions that have signaled transition and drawdown ambitions such as MONUSCO in DRC and UNSOS in Somalia, private-sector partnerships offer one encouraging avenue for implementing positive legacy projects. The Hybrid Solar Power Plant in Baidoa, Somalia is an example of a Power Purchase Agreement between Norwegian firm Kube Energy and the UN mission, UNSOM, as well as the local government of Southwest State. Financial risk guarantees were provided by the World Bank. This project provides clean renewable power for UN operations as well as the local government and offices in the project vicinity. Because the project belongs to Kube and not the UN, there is a clearer path forward to local benefits in the short term and a longer project lifecycle because it won’t end with the mission drawdown. Additionally, Kube and the Somali government have reached an agreement that ownership of the system will turn over to the government after 15 years. Private partnerships that move the UN away from generating its own power and towards being an anchor customer can provide models that guarantee the UN will deliver a positive legacy and wider impact without delay.

Renewable energy infrastructure can contribute to building sustainable livelihoods, fulfilling mission goals, and enhancing confidence in peacebuilding opportunities while building much-needed resilience to climate change. With an uncertain future for multidimensional peacekeeping, UN actors and partners should act with greater urgency to realize the positive legacy benefits of existing peace operations, particularly in Africa.

Cover photo: UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti

Building Legacies for Peace through Renewable Energy Infrastructure: Lessons from Mali

By Isabel Scal

Resilience & Sustainability

In June 2023, the new military government in Mali, with little warning, demanded the UN close its peacekeeping mission in Mali, MINUSMA, precipitating an abrupt and chaotic end to its presence in the country. While there is little precedence for the UN in how fast and fully the new Malian authorities expect the mission’s conclusion, what happened in Mali should be seen as a cautionary tale and could be a foreshadowing of a new era for UN peacekeeping, one that signals the need for new thinking on transitions, different tools, and reconsidered techniques to achieve lasting positive benefits to local communities. Looking at those innovative areas can help the international community accelerate ways for UN missions to have enduring benefits more effectively.

Peace Dividends of Renewables in Fragile States

The fragile countries where peacekeeping missions are deployed are among those facing the most significant climate vulnerability and lowest electricity access. The absence of resilient infrastructure and reliable energy availability contributes to the challenges that host countries face in building stable political systems and ensuring sustained economic development. Developing integrated strategies that can address the unique challenges of climate vulnerability, state fragility, and energy poverty is critical to the wellbeing of a society and ultimately, the success of a UN Peacekeeping mission. Powering Peace’s own data dashboard, which aggregates relevant data for each country, helps to illustrate how these factors are interconnected.

As an international organization with a presence around the world, the UN has a large carbon footprint. Peacekeeping missions are often deployed in fragile settings with limited energy resources, making them among the largest energy consumers in their host countries. The status quo for most missions today is that electricity is self-generated by on-site diesel generators for the mission’s exclusive use. The installation of renewable energy infrastructure operated by the UN can lay the foundation for sustainable Mission programming, helping the UN achieve their own climate goals. Expanding that energy capacity beyond the UN compound’s fence can lead to enhanced energy access for local communities and support a transformation of their own livelihoods. Increased renewable energy resources can also lower the cost of electricity and eliminate the need for diesel fuel supply chains. In many conflict settings, fuel convoys must pass through numerous checkpoints controlled by conflict actors, a negative side effect of diesel dependency that can exacerbate communal conflict and encourage criminal networks. More renewable energy can lead directly to improved economic opportunities for local economic stakeholders.

Positive Legacies in UN Operations

The UN Secretariat unveiled its first Environment Strategy for Peace Operations in 2017. A core pillar of this strategy is that the “wider impact” of peace operations should “take account of environmental impact” and “increase the extent to which their footprint leaves a positive legacy.” Although not part of the original concept of peacekeeping missions, this new strategy codified positive legacy terminology in UN documents even though there is no formal UN definition of positive legacy. The underlying idea is that missions will foster enduring contributions to peace through policy and infrastructure that will explicitly benefit the host country over time. This strategy is a step toward mainstreaming the concept of long-term positive legacy into mission planning. Missions are encouraged to identify projects and activities that can leave a positive and long-term impact from the presence of peace operations.

Peacekeeping liquidation and asset disposal measures were not developed with an eye towards leaving mission assets in countries after the departure of missions. The UN Financial Regulations and Rules indicate that equipment from liquidating a peace operation can only be considered for disposal by gift or by sale at nominal value to a government if it is not required for any other peace operation, other UN activities funded from assessed contributions, or other UN agencies, international organizations, or NGOs. Thus, there is currently no established procedure or process for leaving behind renewable energy infrastructure, much less developing structures to support its operation and possible expansion beyond the mission to benefit the local community. These regulations and constraints are therefore at odds with the stated intentions of positive legacy.

Some UN missions are already sharing renewable energy technology with local stakeholders through Quick Impact Projects and other small-scale programs. However, unless there is a dedicated effort to extend power generation beyond the fence and eventually hand over energy infrastructure, the missions will not realize the full potential of positive legacy opportunities.

UN Geospatial

Dangers of a MINUSMA Precedent

Following Bamako’s urgent demand in June 2023 to terminate MINUSMA, the UN Security Council promptly passed Resolution 2690 later that month, which formalized the end to MINUSMA operations and established a highly ambitious timeframe for its departure. The standard practice for Transition and Liquidation of mission assets is a phased approach, with a 6-12 month period during which the closure plan can be developed. For MINUSMA, the Council insisted on a complete cessation of operations, transfer of tasks, and withdrawal of personnel by December 31, 2023, so the Mission was required to develop and implement its closure and liquidation plans within a compressed timeline. Despite nascent plans to incorporate renewable energy through various power purchase agreements (PPAs) into operations for specific mission sites, any further consideration of transition planning for MINUSMA was just beginning. Given the absence of a longer-term transition plan, MINUSMA was forced to abandon its ambitions for incorporating long-term renewable energy projects into its operations.

Longstanding expectations for the closure of peace operations are for the Security Council to end the mission only after sufficient progress in the fulfillment of the mandate. However, this model has frayed in recent years; MINUSTAH, MINUJUSTH (both in Haiti), and UNAMID (Darfur) all closed prematurely due to lack of political support within the country or complicated Security Council dynamics. The situation in Mali is a warning sign that the template for an organized, UN-initiated closure – when the country has graduated to a more stable peace – cannot be the default expectation. The case of MINUSMA suggests that more host countries may initiate future transitions, with little warning, on accelerated timelines and short of the stated goals of the UN mission. While this shift will not precipitate the collapse of other UN missions, it may reflect the end of an era for large-scale international peacekeeping in Africa. The status quo is likely to persist, but there seems little appetite for a new multidimensional UN peacekeeping mission in the future; no UN peacekeeping missions have been approved since MINUSCA in 2014. At the same time, an international imperative to address conflict through other multinational or regional forces is likely to remain. Given the uncertain life expectancy of large-scale multidimensional missions, which include peacebuilding, civilian services, and human rights protections in addition to miliary policing, transition planning needs to become a standard feature of a mission’s daily operations to future proof it against a sudden closure.

Building positive legacy into the architecture of existing missions and future iterations of peacebuilding systems can contribute to the Mission’s ongoing success by building host community support for the UN presence and its effectiveness, as well as the international community’s confidence in peacekeeping as a model. Infrastructure projects such as renewable energy can contribute to both the lasting success of the mission as well as providing immediate support and benefits to local communities. These projects also offer a way for an upfront investment in positive legacy, while providing the UN with a clear way to achieve their climate commitments, extend renewable energy access, and bolster community resilience while delivering on the ultimate goal of enduring peace and security.

Opportunities for Positive Legacy Prioritization

The changing landscape of UN peacekeeping — more Special Political missions, fewer personnel, and more targeted mandates – should encourage creative solutions and new ways of thinking for future operations. There are several promising approaches that have already begun to address this shift.

Areas of Progress

The Security Council took an important first step in 2021 to highlight peacekeeping transitions as a central consideration rather than an afterthought when it passed Resolution 2594: the first stand-alone resolution on peacekeeping transitions. The resolution calls for an integrated approach to transitions at the earliest possible stage of a peace operation’s life cycle and reinforces the goal of national ownership in development of sustainable peace. However, the resolution neglects to directly reference infrastructure and environmental considerations that will only become more critical in the coming decades. The Secretary-General’s report pursuant to the Resolution included a section on environmental impact, which outlines the importance of renewable energy in the responsible conclusion of missions. Specific language highlights that clean energy infrastructure “would benefit local communities long after the departure of the mission.” While the Secretariat advocates for environmental concerns in the transition process, only the UNSC has the power to establish legally binding requirements. Sidestepping these mandates will mean missions will lack the tools they need to transition successfully.

Additionally, in 2022 and 2023 each UNSC mandate renewal resolution for the “big five” UN peace operations – Mali, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Central African Republic, South Sudan, and Somalia – directly referenced the Secretariat’s Environmental Strategy, including explicit mention of renewable energy in the context of the mission’s positive legacy. Each mandate “emphasises good stewardship of resources and a positive legacy of the mission, and identifies the goal of expanded renewable energy use in missions to enhance safety and security, save costs, offer efficiencies and benefit the mission.” Guidance from the mandate opens the door for RE prioritization in mission programming; the UN must now walk the walk regarding the design and implementation of projects.

Possibilities for Further Integration

While official UN engagement with positive legacy has gained significant traction in recent years at a conceptual level, real adjustments to the transition process and wider impact of peace operations will require concrete changes. One place to start would be the improvement of the Rules and Regulations of the liquidation process which will require broader support from Member States, as only the General Assembly can approve amendments. The changes should include asset disposal measures related to gift or sale at nominal value from a last resort to standard practice, allowing missions to better use their existing assets as part of the broader positive legacy of missions.

In addition, UN country teams should be involved in the transition process through coordination. Multidimensional missions have supposedly been integrated with country teams for over a decade now, but this has faltered in practice. In the context of UN transitions, the UN needs to take integration more seriously and involve country teams both on peacebuilding tasks but also issues related to infrastructure and energy transition, encompassing the broader UN system.

Looking to other missions that have signaled transition and drawdown ambitions such as MONUSCO in DRC and UNSOS in Somalia, private-sector partnerships offer one encouraging avenue for implementing positive legacy projects. The Hybrid Solar Power Plant in Baidoa, Somalia is an example of a Power Purchase Agreement between Norwegian firm Kube Energy and the UN mission, UNSOM, as well as the local government of Southwest State. Financial risk guarantees were provided by the World Bank. This project provides clean renewable power for UN operations as well as the local government and offices in the project vicinity. Because the project belongs to Kube and not the UN, there is a clearer path forward to local benefits in the short term and a longer project lifecycle because it won’t end with the mission drawdown. Additionally, Kube and the Somali government have reached an agreement that ownership of the system will turn over to the government after 15 years. Private partnerships that move the UN away from generating its own power and towards being an anchor customer can provide models that guarantee the UN will deliver a positive legacy and wider impact without delay.

Renewable energy infrastructure can contribute to building sustainable livelihoods, fulfilling mission goals, and enhancing confidence in peacebuilding opportunities while building much-needed resilience to climate change. With an uncertain future for multidimensional peacekeeping, UN actors and partners should act with greater urgency to realize the positive legacy benefits of existing peace operations, particularly in Africa.

Cover photo: UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti

Recent & Related