Global Governance Innovation Network Policy Brief Series

This series provides a platform for leading and up-and-coming authors’ thinking on major contemporary global governance challenges with view to stimulating further debate and influence policy debates. The views expressed in the policy briefs will be of their respective authors and not necessarily reflect those of the GGIN and its partner institutions.

Introduction

Among the major challenges facing global governance reform is the Triple Planetary Crisis: the complex and intertwined impacts of climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution.1The Triple Planetary Crisis: Forging a New Relationship Between People and the Earth”. UNEP. (14 July, 2020) https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/speech/triple-planetary-crisis-forging-new-relationship-between-people-and-earth The world’s forest areas are being hit especially hard by these dynamics: environmental destruction and degradation – especially as illegal deforestation dovetails with contamination of the soil, water, and air (for instance, through illegal gold extraction and forest fires caused by human action) producing a broad gamut of negative social, economic, and environmental impacts. In the Amazon Forest alone, for instance, over 20% of the biome has already been lost to environmental crimes, and vast expanses are threatened by recent surges in these illegal activities. The region is moving towards a tipping point, where trees die off en masse2Boulton, Chris A., Timothy M. Lenton and Niklas Boers, “Pronounced Loss of Amazon Rainforest Resilience Since the Early 2000s” Nature Climate Change 12 (2022): 271-278. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-022-01287-8. Tropical forests in the Congo Basin and in the Borneo region are also undergoing rapid rates of deforestation and degradation.3Butler, Rhett A., “Rainforest Information” (Mongabay: August 14, 2020). https://rainforests.mongabay.com/ For local populations, these activities lead to poor health outcomes, pockets of poverty, and forced displacement, among other impacts. Populations outside forested areas are also affected, for instance through the loss of carbon storage, increased greenhouse gas emissions, and increased water insecurity.

Despite decades of attempts to complement national and subnational responses to these problems through international cooperation, including multilateral approaches.4Abdenur, Adriana E, “What Can Global Governance Do for Forests? Cooperation and Sovereignty in the Amazon” United Nations University Centre for Policy Research/Plataforma CIPÓ (2022). https://cpr.unu.edu/research/projects/global-governance-forests.html there is no global forest treaty – and, given the deepening crisis, we may be out of time for negotiating a full convention. A lack of political will, often expressed through the discourse of national sovereignty, and deeply entrenched economic interests have precluded internationally binding commitments. This means that international cooperation for forests, whether at the global, regional, or transregional levels, remains well below its full potential. In addition, there are few solid international commitments to forests. Instead, a plethora of loose norms, recommendations and responses have emerged – the so-called “toolkit approach,” where the UN and other global governance organizations offer loose recommendations and each state is free to pick and choose how (and even whether) to adopt sustainable approaches to forests. While this approach offers flexibility, it also makes it easy for governments to backtrack on promises and promote predatory use of forest resources. At the same time, a broad variety of actors are engaged in efforts to clean up forest risk commodity chains, from the creation of certification schemes to attempts to boost law enforcement around environmental crimes in individual countries.5See, for instance, Farias, Hilder André Bezerra, Sérgio Luiz de Medeiros Rivero, Márcia Jucá Teixeira Diniz “Negative Incentives and Sustainability in the Amazonian Logging Industry” Nova Economia 27:3, (2016) ,363-391. Yet, without adequate coordination, specific goals and an independent monitoring mechanism to follow these efforts across each commodity chains, piecemeal efforts have limited impact.

Against this background of governance fragmentation and deficits, this policy brief proposes an action and result oriented Responsibility Chains Process, a multi-stakeholder model aimed at convening relevant actors and initiatives in producer and importer countries, coordinating efforts, and producing an umbrella framework to zero illegal deforestation and other socio-environmental and human rights violations associated with key commodities chains pressuring the forest, such as soy, beef, timber and gold. The policy is divided into three sections: The first notes key gaps in global governance for forest protection. Next, the brief explains the concept of Responsibility Chains. The last and final part of the policy brief specifies recommendations for kickstarting the initiative and linking it to relevant global frameworks, including at the United Nations (UN).

Gaps in global governance for forest protection

According to the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports,6“Sixth Assessment Report: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability” IPCC. (2022). https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/resources/press/press-release/ the world is not on track to meet the Paris Agreement goal to hold the increase in global average temperature to well below 2ºC, preferably to 1.5 ºC, compared to pre-industrial levels. The window of opportunity to prevent catastrophic impacts is closing, rapidly. At the same time, environmental degradation is intensifying in many parts of the world. In forest areas, illegal deforestation and degradation has become an urgent planetary issue. Forests help to stabilize the global climate, regulate ecosystems, play a key role in the carbon cycle, and are home to 80% of the planet’s terrestrial biodiversity. Globally, 1.6 billion people – almost 25% of the world’s population – rely on forests for their livelihoods, many of whom are in the world’s poorest countries.

In forest areas, climate change and environmental destruction dovetail, with disastrous consequences, not only from a climate and environmental angle, but also from a socioeconomic one. Populations in forest areas – many of whom are from indigenous and other traditional communities – suffer loss of livelihoods and experience surging organized crime and violence, pockets of poverty, and human rights violations. Beyond those regions, deforestation has regional and global impacts, through direct and indirect greenhouse gas emissions that affect weather patterns and the climate. In the Amazon – the largest tropical forest in the world – rates of deforestation are reaching new records,7Spring, Jake, “Brazil’s Amazon Deforestation Sets First-Quarter Record Despite March Dip.” Reuters, (April 8, 2022) https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/brazils-amazon-deforestation-sets-first-quarter-record-despite-march-dip-2022-04-08/ primarily due to the expansion of export-driven agriculture, ranching, as well as illegal logging and gold mining. But other forest areas, such as the Congo Basin, in Africa, and the Borneo Forest in Southeast Asia, are also the sites of deforestation and other environmental crimes on a massive scale.8Butler, 2020.

Local communities in forest areas, as well as consumer groups in countries that import products driving most of this deforestation, have been vocal in pressing for more effective policies and cooperation against illegal deforestation. Yet national policies vary immensely over time and across space, and often successes are followed by significant reversals, as in the case of Brazil. Other actors, from private sector companies and associations to civil society entities, are implementing specific responses, such as improved tracking of illegal deforestation to certification schemes for products like timber and beef. Yet these efforts remain fragmented; as a result, even when an initiative is successful, environmental crime perpetrators will find another “weak spot” along the chain. For instance, after policies were implemented in Brazil to curb the predatory expansion of ranching in forest areas by preventing major meatpackers from buying cattle from deforesters in the Amazon, major corporations resorted to “cattle washing”, taking advantages of the lack of animal traceability to conceal sales of cattle raised in illegal areas through false declarations of origin. Investigations found that, in addition to widespread illegal deforestation, these sales were associated with slave labor.9Campos, André “World’s biggest meatpackers buying cattle from deforesters in Amazon” (Mongabay: 19 September 2019) https://news.mongabay.com/2019/09/worlds-biggest-meatpackers-buying-cattle-from-deforesters-in-amazon/

At the same time, existing global governance solutions to deal with forest-related problems are both scattered and insufficient. The promise of a global treaty on forests put forth at the 1992 United Nations Earth Summit never became a reality, limited by strong private sector interests and the discourse of national sovereignty, which a number of Global South countries tend to mobilize when their policy elites are distrustful of the motivations driving North proposals for forest conservation. And, given that negotiating global conventions takes years, if not decades, humanity may not have time to reach such a comprehensive binding agreement. Thus, more agile and realistic solutions are needed to tackle this dimension of the global climate/ecological challenge.

In the absence of a legally binding framework for forest protection, new mechanisms and soft law initiatives have emerged. This includes commitments such as the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use,10United Nations Climate Change Conference UK 2021. Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use. (Glasgow: 2021). announced at COP26, and efforts around Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+), through which countries are financially compensated for conserving and restoring their forests, but which are unevenly implemented and have yielded mixed results. And, while a myriad of actors – from civil society, some states and private sector companies – are engaged in cleaning up “supply chains,” these efforts seldom coordinate with one another. In addition, they are generally disconnected from broader frameworks at the United Nations (UN), the World Trade Organization (WTO), the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the World Economic Forum (WEF), the G-20 and other relevant global and regional governance bodies. These include the Sustainable Development Goals, the Paris Agreement, and key human rights frameworks like the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime.

In addition, the use of terms like “supply chains” reflects two disconnects. First, this term reflects the point of view of importer countries, and therefore tends to focus more narrowly on the role of producer countries (i.e., those that have tropical forests) and other stakeholders there, such as private sector companies operating in developing countries. On the other hand, not enough attention is being paid to the roles of international trade, investment, and consumption patterns. Second, “supply chain” is a business-centered concept, whereas the production, trade, and consumption of forest commodities is a multi-faceted dynamic involving all sectors: state, civil society, local communities, private sector, and finance.

There is thus a need to rethink global governance of forests. We need:

- A path that is more effective and action-oriented.

- To improve accountability for climate and socio environmental harm, as well as human rights violations that take place along the entire chain.

- A multi-stakeholder model that allows for meaningful participation by all sectors both in producer and importer countries.

- To link climate, environment, and human rights issues to trade and investments more concretely.

- To better connect initiatives on commodity chains to relevant frameworks in global governance, including the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the Paris Agreement, the UN Secretary General led Our Common Agenda, the agendas of the G7 and G20, and Just Transition frameworks.

- To build on existing commitments, such as the Glasgow Leaders Declaration on Forests and Land Use and the Global Methane Pledge, in ways that lead to action and results.11Global Methane Pledge. (Glasgow: 2021).

- A comprehensive, Global South-led effort (since key producers are developing countries) that includes the meaningful participation of indigenous peoples and other traditional communities, as well as multi-sector stakeholders in the Global North.

Promoting global governance for forests: What are Responsibility Chains?

In order to promote a more effective global governance for forests, we propose the creation of a Forest Governance Responsibility Chains Process. Unlike supply chains, responsibility chains refer to the interconnected sets of socio-environmental relations that link commodity producers to consumers, from the source of finance and primary production to extraction and manufacturing (when applicable), exporting and importing, all the way to final consumption. The concept of Responsibility Chain acknowledges the roles of multiple actors and thus demands accountability from all, and all along the chain: the state (both producers and importers), private sector, financing, and consumer groups. Responsibility chains also entail international cooperation among

producer and consumer countries, bridging North-South divides that have often stymied international cooperation around forest issues.

They can also help overcome the “national sovereignty hurdle” by promoting Global South leadership (and bringing on board Northern countries in collaborative partnerships) while meaningfully incorporating indigenous peoples, companies, government actors, NGOs, and international organizations. Finally, Responsibility Chains aims to address (a) the lack of buy-in from “spoilers,” through negative and positive incentives (such as strengthened law enforcement cooperation and certification systems), and (b) avoid greenwashing by incorporating monitoring and evaluation in ways that go beyond loose pledges and commitments, and therefore actually drive a behavior change.

There are many reasons why Responsibility Chains are promising. For instance,

- they spread accountability throughout key systems and communities;

- they entail a multi-stakeholder model;

- they represent a politically realistic and potentially much more effective approach than currently-fragmented solutions;

- they promote greater awareness of the need for “clean” commodity chains among consumers, including those in importer countries, by engaging with consumer groups and allied policymakers;

- they build on already-existing initiatives, including major 2-year project by Plataforma CIPÓ and ongoing work by the Exponential Roadmap initiative.

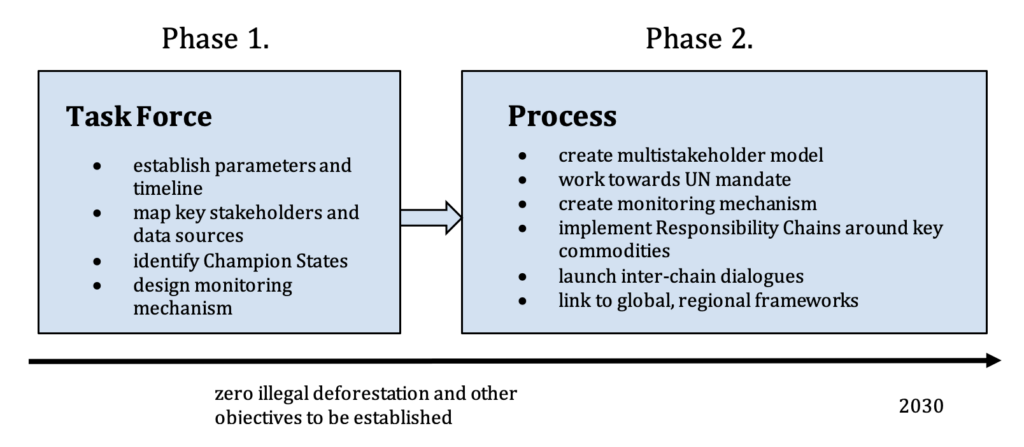

In the first phase of the Process, a Responsibility Chains Task Force of approximately 6 months to 1 year of duration will bring together key experts to explore the parameters of the Process; map relevant actors, including potential “Champion States”; identify relevant existing initiatives; and draft an Action Plan for a multi-stakeholder process that could convene relevant actors and initiatives, coordinate efforts, and produce an umbrella framework around the concept of Responsibility Chains, with the goal of zeroing illegal deforestation by 2030 (the goal set out in the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use at COP26), as well as other socio-environmental violations linked to key commodities chains.

Strategy for reform: Where to start?

There is an opportunity to promote more innovative and effective forest governance:

- unprecedented awareness of and concerns about the planetary crisis, especially among youth;

- there are new sources of leadership, not only at the local level (especially by indigenous and, traditional communities and grassroot organizations) but also at the regional and global levels (for instance, states that can act as champions of the cause, from Costa Rica to France);

- innovative private sector actors are either under increasing pressure to adopt Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) and other sustainability practices, or are leading the way;

- there is no need to completely reinvent the wheel; the components of a new governance for forests are already in place;

- emerging technologies hold promise for prevention and detection of deforestation and other socio-environmental impacts, provided that they are collectively adopted by multiple actors, scaled up and accompanied by transparent and inclusive monitoring and accountability mechanisms.

How will the process unfold? In the first year of the initiative, the Responsibility Chains Task Force will explore the basic parameters and priorities of the Process using evidence-based data as well as a mapping of key political processes, relevant spaces, essential stakeholders (including “Champion States”) and existing related efforts, such as improvements that can be tapped into and scaled up, such as new technologies for tracking commodities internationally and the creation of certification schemes. Based on existing data, it is possible to identify, using quantitative data, the commodities that strongly contribute to climate change, which are highly associated with environmental crimes leading to widespread deforestation, pollution, and contamination. Data is also available for estimating the greenhouse gas emissions and socio-environmental impacts of these chains, as well as other negative impacts, such as negative health outcomes and violent crime, including homicide rates. Starting with ensuring zero deforestation and zero tolerance for other social environmental violations along one or two key Responsibility Chains will build trust in the capacity of global governance to address the Triple Planetary Crisis of climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution, and then more chains can be added to the effort.

Examples of key chains pressuring forest areas include:

- Beef: Ranching and production of beef is the main driver of illegal deforestation in the world’s tropical forest.12Madeiro, Carlos “Pecuária responde por 75% do desmatamento em terras públicas na Amazônia“, Uol, (October 10, 2021). As demand for beef from global markets continues to rise, vast tracts of forested land are being cleared for raising cattle.

- Soybeans: Soy commodity chains are strongly associated with illegal deforestation and fires caused by human activity in the Amazon Basin. In much of the region, the expansion of export-oriented agriculture is driving invasions and deforestation of public lands, including Indigenous Lands, Conservation Units and other protected areas. Major companies have been linked to efforts to circumvent a moratorium on purchases of soy associated with illegal deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon, allowing “dirty” soy to enter international trade.13Terra de Direitos “15 Anos da Moratória da Soja: a Mágica de Dados que Fez o Agronegócio Crescer e a Floresta Desaparecer” Amazonia.org.br.(28 July 2021) https://amazonia.org.br/15-anos-da-moratoria-da-soja-a-magica-de-dados-que-fez-o-agronegocio-crescer-e-a-floresta-desaparecer/.

- Illegal Timber: The high demand for timber products makes illegal logging another primary driver of deforestation and other environmental crimes in the Amazon. Illegal logging in the region is strongly associated with road and other infrastructure construction. Timber extraction often targets high value species such as ipê wood (Handroanthus spp.) and mahogany, but even selective extraction has a deleterious effect on surrounding flora and fauna.

- Gold: Instability in global financial markets has led to a surge in the price of gold. Its illegal extraction in the Amazon is causing widespread destruction of riverbeds and contamination of waterways and food chains.

The Task Force will then launch its draft Action Plan and Timeline for the Responsibility Chains Process, with a vision for bringing together key actors among producer and consumer states, private sector actors and finance firms, and civil society entities around a shared vision, concrete goals and clear monitoring mechanisms for cleaning forest risk commodity chains and promoting more sustainable approaches. Although, as the next section explains, in light of the need for meaningful participation from the outset of not only states but also of multisector non-governmental and subnational actors, the Process may begin outside the UN, led by a coalition of civil society entities and private sector actors, and eventually it can come under a UN mandate.

How to link Responsibility Chains to Global Governance?

There are precedents that may provide inspiration and lessons learned. On example, from which positive and negative lessons can be gleaned, is the Kimberley Process certification scheme for conflict diamonds.14The Kimberley Process: https://www.kimberleyprocess.com/ This international, multi-stakeholder initiative was created to increase transparency and oversight in the diamond industry in order to eliminate trade in conflict diamonds, or rough diamonds sold by rebel groups or their allies to fund conflict against legitimate governments. It was launched by diamond producing states in Africa and has brought together governments, the private sector (including industry association and specific companies) and civil society (especially in the role of independent monitors) to curb the trade in conflict diamonds in Africa – underpinned by a UN mandate. As of 2022, 81 countries, representing 99.8% of the global production of conflict diamonds, have joined the Kimberley Process.

The certification of the Kimberley Process has major gaps that curtail its effectiveness – for instance, it focuses solely on the mining and distribution of conflict diamonds specifically, rather than diamonds more broadly. However, lessons can be learned from this model and applied to other products, including in places where the discourse of national sovereignty has posed considerable hurdles to international cooperation around climate and environmental issues. In particular, it offers a way to bring on board key countries and other stakeholders without having to negotiate a full forest protection treaty, which is a protracted process.

In the Amazon, there are multiple ongoing efforts to clean up supply chains for commodities that are pressuring the forest, such as beef, timber, soybeans, and gold. However, they run up against challenges that include destructive environmental policies and poor enforcement of environmental laws in producer countries on the one hand; and on the other, flawed due diligence protocols and weak mechanisms (and even inadequate legislation) in importing countries to ensure administrative and criminal sanctions against actors acquiring and profiting from products from environmental. Major gaps also remain in international cooperation among law enforcement agencies and other stakeholders involved in tackling illicit activities across supply-consumption chains.

Key recommendations

In order to kickstart the Responsibility Chains initiative and link it with global governance, the following measures are recommended:

- A Task Force on Responsibility Chains should be created to design the process in greater detail; identify key stakeholders (states, private sector actors, finance firms, civil society entities, and international and regional organizations); and select the commodity chains that have the best chances of bringing about change, for instance elimination of illegal deforestation. Over the course of a period of 6 months to 1 year, the Task Force should also provide a detailed Action Plan for:

- Identifying key actors around major forest risk commodity chains and bringing them onboard with clearcut and feasible goals for cleaning those value chains and promoting more sustainable alternatives to development in forest regions;

- Developing mechanisms to facilitate a more predictable and efficient cooperation between stakeholders in producing and importing countries, with a focus on environmental monitoring and law enforcement agencies tasked with tackling socio-environmental violations, financial crimes, and other related illicit activities at the producing and consumption ends

- Linking up ongoing initiatives on clean supply chains, both at the UN and in other organizations, such as the OECD, to global normative efforts around business, human rights, and prevention of illegal deforestation.

- Incorporating the concept of Responsibility Chains into major spaces for discussion of global governance, including the United Nations, G7, G20, OECD and BRICS, starting at COP27.

- Through the United Nations,

- Existing data and capabilities can be harnessed via the UN Environmental Programme (UNEP), the Global Compact, the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), the UN Office for South-South Cooperation (UNSSC), and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), among others, as well as key regional organizations and partner institutions such as the World Trade Organization (WTO).

- Responsibility Chain data (for instance, on the environmental, social and climate impacts of supply chains) can be collected and analyzed via the Futures Lab proposed by the UN Secretary General’s Our Common Agenda report, and used for projections of environmental degradation and destruction, as well as associated social impacts on human rights, health, income and wellbeing; The concept can also be incorporated into the coordination mechanism foreseen in Our Common Agenda’s Summit of the Future and the Declaration on Future Generations15;”Secretary General’s Report on ‘Our Common Agenda'”, United Nations (2021) https://www.un.org/en/un75/common-agenda.

- A narrative shift is needed from supply chains, which reflect the viewpoint of consumers, to that of responsibility chains. The concept – and its role in Global Climate Governance – should be explored in key global governance events, such as COP27 and the Summit of the Future, as well as discussions of global governance improvement that are led by civil society, including future Global Policy Dialogues (especially that under planning for Recife, Brazil, on the specific topic of the Triple Planetary Crisis) organized by Plataforma CIPÓ through the Global Governance Innovation Network (GGIN) and other partners.16“Global Governance: CIPÓ co-organizes Global Policy Dialogue during ACUNS Annual Meeting, Plataforma CIPÓ, (21 June 2022) https://plataformacipo.org/en/events/global-governance-cipo-co-organizes-global-policy-dialogue-during-acuns-annual-meeting/.

- The concept of Responsibility Chains should be promoted at the World Trade Organization (WTO) as a way to better incorporate supply-consumption chains into international trade frameworks and initiatives. This looks more promising after the 12th Ministerial Conference, held in June 2022, which yielded breakthroughs such as an agreement to prohibit harmful fisheries subsidies.17“Twelfth Ministerial Conference” WTO, (2022) https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/minist_e/mc12_e/mc12_e.htm

- At a political level, the Alliance for the Protection of Tropical Forests can help galvanize political will to incorporate Responsibility Chains into the discourse and major international efforts to address the root causes and international dynamics behind environmental crimes such as deforestation, pollution, and contamination in forest areas.

In sum, conceptualizing commodity chains with forest risks as Responsibility Chains and building a new governance arrangement around this concept will allow accountability for illegal deforestation and other environmental crimes, as well as associated human rights violations, to be spread across the entire chain, from producer to consumer countries. Rather than reinvent the wheel, the initiative builds on existing yet scattered efforts that need improved coordination, a shared vision and specific objectives. The Responsibility Chains initiative will provide a space for multiple stakeholders, from states to private sector actors, finance firms to civil society entities to work together under a shared goal in order to clean up commodity production, trade and consumption of environmental harm, human rights violations and other negative impacts. Starting with key commodities like soy, beef, timber and gold, and then promoting cross-sectoral dialogues linked to key global frameworks on business, human rights and trade, will enable the creation of a multi-stakeholder governance model to effectively stop illegal deforestation – and all its associated social, climate and environmental harms – by 2030.

Authors

Adriana Erthal Abdenur is a Brazilian policy expert and the co-founder and Executive Director of Plataforma CIPÓ, an independent, women-led institute based in Brazil and dedicated to issues of climate, governance and peace in Latin America and across the Global South

Maiara Folly is Programme Director at Plataforma CIPÓ and a Brazilian international relations and public policy researcher, based in London. She leads policy-oriented research and advocacy projects on environmental crime, climate justice, migration, and international cooperation.

Maja Groff, Esq. is an international lawyer based in The Hague, and is Convenor of the Climate Governance Commission, which seeks to propose high impact global governance innovations adequate to meet the climate challenge.

Editorial Team: Joris Larik (series editor), Muznah Siddiqui (deputy editor), Richard Ponzio (project lead), and Ceyda (intern). This policy brief benefitted from the feedback received at the Roundtable on Global Governance Innovation at the 2022 Annual Meeting of the Academic Council on the United Nations System in Geneva, at which Prof. Roger served as discussant.

The Stimson Center

The Stimson Center promotes international security and shared prosperity through applied research and independent analysis, global engagement, and policy innovation.

For three decades, Stimson has been a leading voice on urgent global issues. Founded in the twilight years of the Cold War, the Stimson Center pioneered practical new steps toward stability and security in an uncertain world. Today, as changes in power and technology usher in a challenging new era, Stimson is at the forefront: Engaging new voices, generating innovative ideas and analysis, and building solutions to promote international security, prosperity, and justice.

More at www.stimson.org.

About the Global Governance Innovation Network

The Global Governance Innovation Network brings world-class scholarship together with international policy-making to address fundamental global governance challenges, threats, and opportunities. Research will focus on the development of institutional, policy, legal, and normative improvements in the international global governance architecture. GGIN is a collaborative project of the Stimson Center, Academic Council on the United Nations System (ACUNS), Plataforma CIPÓ, and Leiden University.

About Plataforma CIPÓ

Plataforma CIPÓ is an independent, non-profit think tank based in Brazil, led by women and dedicated to the themes of climate, governance and peace and security in Latin America and the Caribbean and, more broadly, across the Global South. CIPÓ’s efforts are designed to support the work of local and national governments, international organizations, civil society entities and the private sector to develop effective responses to the challenges of the socio-ecological crisis, including preventing environmental crimes, cleaning up commodity chains, and promoting more effective global governance around climate and environmental issues. CIPÓ has staff in four regions of Brazil, as well as the UK, the United States and the European Union.

About the Climate Governance Commission

The Climate Governance Commission aims to fill a crucial gap in confronting the global climate emergency by developing, proposing and building partnerships that promote feasible, high impact global governance solutions for urgent and effective climate action to limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C or less. Innovative new perspectives, deploying new levels of collective wisdom and ingenuity, will be required to tackle current existential planetary risks. The Commission’s Interim Report, Governing Our Climate Future (October 2021) explored a wide range of global governance innovation proposals across various thematic areas implicated in the climate challenge, including; the mobilization of new levels of global finance, facilitating necessary labor markets transitions at scale, notions of climate and security, legal accountability, and international institutional reform, among others.

Notes

- 1The Triple Planetary Crisis: Forging a New Relationship Between People and the Earth”. UNEP. (14 July, 2020) https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/speech/triple-planetary-crisis-forging-new-relationship-between-people-and-earth

- 2Boulton, Chris A., Timothy M. Lenton and Niklas Boers, “Pronounced Loss of Amazon Rainforest Resilience Since the Early 2000s” Nature Climate Change 12 (2022): 271-278. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-022-01287-8

- 3Butler, Rhett A., “Rainforest Information” (Mongabay: August 14, 2020). https://rainforests.mongabay.com/

- 4Abdenur, Adriana E, “What Can Global Governance Do for Forests? Cooperation and Sovereignty in the Amazon” United Nations University Centre for Policy Research/Plataforma CIPÓ (2022). https://cpr.unu.edu/research/projects/global-governance-forests.html

- 5See, for instance, Farias, Hilder André Bezerra, Sérgio Luiz de Medeiros Rivero, Márcia Jucá Teixeira Diniz “Negative Incentives and Sustainability in the Amazonian Logging Industry” Nova Economia 27:3, (2016) ,363-391.

- 6“Sixth Assessment Report: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability” IPCC. (2022). https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/resources/press/press-release/

- 7Spring, Jake, “Brazil’s Amazon Deforestation Sets First-Quarter Record Despite March Dip.” Reuters, (April 8, 2022) https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/brazils-amazon-deforestation-sets-first-quarter-record-despite-march-dip-2022-04-08/

- 8Butler, 2020.

- 9Campos, André “World’s biggest meatpackers buying cattle from deforesters in Amazon” (Mongabay: 19 September 2019) https://news.mongabay.com/2019/09/worlds-biggest-meatpackers-buying-cattle-from-deforesters-in-amazon/

- 10United Nations Climate Change Conference UK 2021. Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use. (Glasgow: 2021).

- 11Global Methane Pledge. (Glasgow: 2021).

- 12Madeiro, Carlos “Pecuária responde por 75% do desmatamento em terras públicas na Amazônia“, Uol, (October 10, 2021).

- 13Terra de Direitos “15 Anos da Moratória da Soja: a Mágica de Dados que Fez o Agronegócio Crescer e a Floresta Desaparecer” Amazonia.org.br.(28 July 2021) https://amazonia.org.br/15-anos-da-moratoria-da-soja-a-magica-de-dados-que-fez-o-agronegocio-crescer-e-a-floresta-desaparecer/.

- 14The Kimberley Process: https://www.kimberleyprocess.com/

- 15;”Secretary General’s Report on ‘Our Common Agenda'”, United Nations (2021) https://www.un.org/en/un75/common-agenda.

- 16“Global Governance: CIPÓ co-organizes Global Policy Dialogue during ACUNS Annual Meeting, Plataforma CIPÓ, (21 June 2022) https://plataformacipo.org/en/events/global-governance-cipo-co-organizes-global-policy-dialogue-during-acuns-annual-meeting/.

- 17“Twelfth Ministerial Conference” WTO, (2022) https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/minist_e/mc12_e/mc12_e.htm