Paralysis of the Security Council and Attempts to Reform It

The Russian aggression of Ukraine invoked fundamental questions as to the relevance of the United Nations (UN) and its ability to prevent wars and restore peace. Such challenge of relevance is not new, however, when one of the five ‘guardians of peace’ not only brutally invades a peaceful neighbor, but commits widespread war crimes and threatens the rest of the world with nuclear weapons, the need to reimagine the UN Organization and to revise its Charter becomes greater than ever.

A year after the aggression, on 23 February 2023, the UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, otherwise a very polite diplomatic person, delivered the strongest ever condemnation against a permanent member of the Security Council by any Secretary-General in history. He named the Russian invasion of Ukraine an “affront to the global collective conscience”, a violation of everything that the UN Charter and international law are about, a “challenge to cornerstone principles and values of the multilateral system.”1Guardian, 23 February 2023, Russian invasion ‘an affront’, says UN chief, as assembly meets on Ukraine. Accessed https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/feb/23/un-chief-condemns-russian-invasion-ukraine-united-nations-assembly-vote-peace-motion On 27 February 2023, with similar determination, Guterres condemned Russia for “widespread death and destruction in Ukraine, for the most massive violations of human rights we are living today, for serious violations of international humanitarian law against civilians and prisoners of war, for hundreds of cases of enforced disappearances”.2UN News, 27 February 2023, Human Rights Council: Russia responsible for ‘widespread death and destruction’ in Ukraine. Accessed https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/02/1133927 Invading Ukraine, Putin and other Russian leaders acted contrary to the highest ideals for which their own grand-parents perished in World War II – in unrivalled historical paradox – sacrificing their lives to create a world without wars. Intervening in Georgia in 2008, arming Bashar al-Assad and engaging in lethal airstrikes against civilian objects in Syria, annexing Crimea and ferociously attacking Ukraine, all these were undertaken by one of the five powers, initially provided with a permanent membership and veto in the UN Security Council to do exactly the opposite – to maintain international peace.3SC/15172 from 12 February 2023 at https://press.un.org/en/2023/sc15172.doc.htm

Calls for reforming the Security Council go back for over thirty years, when in 1993 the UN General Assembly (GA) created an Open-Ended Working Group on the Question of Equitable Representation and Increase in the Membership of the Security Council. In 1997 Ismael Razali, then Chairman of this Open-Ended Working Group, initiated drafting of a GA resolution to adopt a three-stage plan to increase the membership from 15 to 24 states by adding five new permanent members without veto, and four non-permanent members. In 2005 Kofi Annan in his Report “In Larger Freedom” presented two specific models – “A” and “B” – and encouraged the UN member-states to discuss and agree on one of them.4In Larger Freedom: Towards Development, Security and Human Rights for All: Report of the Secretary-General – United Nations and the Rule of Law. United Nations and the Rule of Law. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://www.un.org/ruleoflaw/blog/document/in-larger-freedom-towards-development-security-and-human-rights-for-all-report-of-the-secretary-general/. In 2015, the author of this brief combined the models “A” and “B” in a composition “8+8+8”.5Popovski, Vesselin, “Innovating the Principal Organs of the United Nations”, in Willian Durch, Joris Larik, Richard Ponzio (eds) Just Security in an Undergoverned World ( Oxford UP 2018) Another well-elaborated recent initiative to reform the Security Council is “Elect The Council”6https://electthecouncil.org/ which also takes into account advantages and disadvantages of previous proposals. In 2020 this author proposed establishing a Peacebuilding Council, a Climate Security Council, and a Health Security Council7Popovski, Vesselin. “Towards Multiple Security Councils.” UN75 Global Governance Innovation Perspectives. Stimson Center. June, 2020. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://www.stimson.org/2020/js2020-towards-multiple-security-councils/. – new organs that assist the Security Council in sharing the workload and financing of international peace and security, representing more states, amplifying more voices, bringing more expertise and commitments. While the Security Council addresses urgent threats to the peace, a Peacebuilding Council – an upgrade and enhancement of the existing Peacebuilding Commission (PBC) – takes care of long-term tasks of economic reconstruction, political consolidation, institution-building, security sector reforms, rule of law etc.

New Agenda for Peace

In September 2021 the Secretary-General’s Report “Our Common Agenda” (OCA)8Guterres, António. Our Common Agenda: Report of the Secretary-General. September 2021. Accessed December 15, 2022.

https://www.un.org/en/content/common-agenda-report/assets/pdf/Common_Agenda_Report_English.pdf. urged states to undertake a profound strengthening of the UN System and address security challenges with interconnected responses through reinvigorated multilateralism.9Ibid. However, it did not say anything new on the Security Council’s reform, comparing for example with the 2005 Report “In Larger Freedom”. It listed what has already existed – regular consultations with a broader range of actors, including regional organizations; public commitments to exercise restraint on the veto; and expanding the use of informal mechanisms (Arria-formula).10Guterres, Our Common Agenda, 77.

Most UN reforms shy away from mentioning any UN Charter amendments, presuming that we are destined to live with this Charter forever. Accordingly, proposals that depend on Charter amendments, are usually rejected as unrealistic. Compared with previous reports, the OCA suggested slower gradual little steps, expected to bring efficiency over time. The problem with such a low-common-denominator approach is that by the time it is implemented, the dynamism of global changes makes the goals and methods obsolete and inefficient.

The OCA was modest and lacked ambition. It initiated a “New Agenda for Peace” (NAfP), but there was very little new about it. It appealed to innovate, de-escalate cyber risks, establish legal limits on autonomous weapons – basically recycling existing well-known ideas. It asked states to prioritize responses to violence from criminal groups inside their borders and address domestic violence, which is hardly anything new and does not resemble any truly international agenda. It went into discussing many possible elements of broader “security”, but paid very minimal attention to “peace”. Effectively, the NAfP turned out not to be “New”, not to be really an “Agenda”, and had very little about “Peace”. Probably its best idea – to repurpose the Trusteeship Council to address future generations – was dropped from further conceptualization, exactly because of a fear that it needs UN Charter amendment.

The High-Level Advisory Board on Effective Multilateralism, convened to elaborate further steps arising from OCA, came up with six transformational shifts, the first of these being to empower equitable effective collective security arrangements to address risks extending beyond military threats and accelerate de-nuclearization efforts. Sadly, it did not say much about the Security Council’s reform, even less on the right to veto. Neither did the Secretary-General, when he initiated eleven Policy Briefs (A/77/SPC.1), one of these on the NAfP. The ambition was to articulate a new vision on peace and security, to address all forms and domains of threats, taking a holistic view of the whole peace continuum from prevention, conflict resolution and peacekeeping to peacebuilding.11A/77/CRP.1 from 7 February 2023 Nothing very “new”, we all know this well from the time of Boutros-Ghali 30 years ago. Or to take the appeal for a comprehensive approach, linking peace, sustainable development and human rights, and remind that this is what Kofi Annan repeatedly wrote and spoke about. The NAfP mentioned a new generation of peace enforcement missions and counter-terrorist operations, synchronizing global and regional efforts, it made a call for disarmament and arms control to be back in the centre of peace and security, and to focus on threats emerging from non-regulated artificial intelligence and cyber-warfare – a lot of deja-vu, without much of novelty and elaboration.

One important proposal in the OCA was the creation of an Emergency Platform, a new body, capable to respond to complex global crises12Ibid., 60–66., by rapidly convening relevant UN organs, key country groupings, international financial institutions, regional bodies, civil society, private sector, subject-specific industries, think tanks. The Emergency Platform analyses a particular crisis, identifies relevant actors and the tasks they are expected to undertake, ensures funding, mechanisms for surge capacity, focal points and protocols to promote interoperability with existing crisis-specific arrangements. The growing number of climate disasters and displacements amplify the need for Emergency Platform, which not only coordinates responses, but also anticipates needs, risks and vulnerabilities. Resources and investments in anticipatory action are vital to saving people at risk. The operational success of the Platform is supposed to rehabilitate the reputation of the UN, build support for global governance, provide political leadership to coordinate effective multilateral action, advocacy and accountability, with more direct and large participation of stakeholders.

One jeopardy for the Emergency Platform would be how to overcome potential blocking from the permanent members of the Security Council, who may prefer crisis decisions to be taken in smaller and non-representative gatherings, rather than in the larger UN. The Emergency Platform, therefore, would flourish, only if the P-5 and their veto does not affect its work, and this applies to all other parts of the UN too. The elimination of the veto, instead of being regarded as a taboo, should become part of the conversation on all other excellent proposals for global governance innovation, such as UN Parliamentary Assembly, UN Emergency Peace Force, Global Environmental Agency, Resilience Council etc. The elimination of the veto would open the doors and facilitate everything else, that the UN needs to do better in the future.

There is no better time to start a discussion on amending the UN Charter, than during the forthcoming in September 2024 Summit of the Future (SOTF). If SOTF does not open such a conversation, it might not be remembered as Summit of the Future. What will that “future” be, if the most fundamental problem at the heart of the Organization – the veto – continues to allows aggressors and war criminals to be untouchable and immune for their crimes? The UN will remain as irrelevant as it currently is, when future vetoes continue to shelter aggressors from accountability.

Eliminate the Veto Power

No other UN Charter provision has been criticized more than the veto, yet, the lack of willingness to talk about its abolishment is inexplicable. A rough calculation of how many people died only in the last decade because of vetoes in the Security Council – in Syria, Yemen, Myanmar, Sudan, Ukraine, Gaza and elsewhere – would give us an horrific total of over a million civilians. The veto is not only obsolete, but also a life-threatening provision. Do we want in a decade from now – perhaps after another million die – to look back at 2024 and ask why we did nothing to eliminate the veto?

Eighty years after the World War II it is high time to stop repeating and believing in two myths:

- “Without the veto, the UN would have been impossible”. This is a counter-factual statement – nobody really knows what would have happened, if many countries, unhappy with the veto in 1945, refused to sign the Charter. Maybe the life of the League of Nations would have be prolonged, maybe few years later, a different United Nations, without veto, may have emerged.

- “The veto saved us from a World War III”. Another counter-factual and wrong statement. Can anyone tell which veto, when, in what situation, by whom, saved us from World War III? Was the veto used, or even considered, for preventing the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis? Not at all. Was the veto helpful to avoid the Vietnam wars? Or the Afghanistan wars? Or the Russian aggression in Ukraine? Exactly the opposite, it was the veto, that made Russia and other P-5 members aggressive and unaccountable.

One can understand why in 1945 the small and medium powers agreed to the veto – they honestly and nobly expected the five big powers to remain united, to cooperate and to maintain international peace and security. One cannot understand why in 2024 the small and medium powers (whose number quadrupled in the eight decades since) do not stop regarding the veto as a taboo. In March 2022 in a speech at the Security Council the Ukrainian President Zelensky compared the right to veto with the “right to die.”13“Ukraine’s President Calls on Security Council to Act for Peace, or ‘Dissolve’ Itself.” UN News. April 5, 2022. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/04/1115632. The abuse of the veto damages the whole UN system, which otherwise could be well-structured and capacitated to undertake extensive live-saving operations. It produces not only paralysis in collective measures, but also destroys the core international legal fabric by allowing an escape route for aggressors and war criminals. It is time to end it.

Article 109 Review Conference

Back in 1945 the veto was not acceptable for many founding members of the UN. China was happy to drop it at the San Francisco conference, if the other big powers agree, but the USA and the UK were hesitant, till at the end Stalin prevailed.14Simma, Bruno (and others) The Charter of the United Nations: Commentary 3rd ed. Oxford UP 2012 P. 18 Poland, Australia, New Zealand, Brazil and the rest of Latin America, being unhappy with the veto, drafted Art. 109 of the Charter, insisting to review the Charter and eliminate the veto in a General Conference convened at latest by 1955.

It is worth reminding what discussions did the UN founders have about the veto as early as in San Francisco in 1945 and at the first GA Session in 1946. Many raised concerns with the veto, regarded it as a temporary gift to the five victors of World War II, and were prepared to remove it at the General Conference in 1955.15Rao, K. Krishna. “The General Conference for the Review of the Charter of the United Nations.” Fordham Law Review, vol. 24, no. 3, Autumn, 1955, pp. 356-368. The delegation of China stressed that the veto might never be used, that the P-5 will act on behalf of all states and ratify amendments adopted by the GA. The delegation of the UK also stated that, if the GA adopts amendments of the Charter with two-thirds majority, the P-5 will accept these. Most significantly, the Interim Committee found the formula how to avoid the obstacle of mandatory ratification by the P-5, writing that “the Charter, after being revised bya general conference called for that purpose, would become a new treaty which would incorporate its own provisions on the method of its ratification. This new treaty would then come into force in accordance with those provisions without regard for Articles 108 and 109 of the present Charter”.16Ibid, p. 367

The road to the elimination of the veto lies in two steps:

- The GA under Art. 108 adopts a Resolution with two-thirds majority, amending Art. 27/3 and removing the veto. If this amendment is not ratified, then:

- This same two-thirds majority of the GA convenes Art. 109 General Conference to review the Charter. They do not need permission from anybody to do that, Art. 109 is clear that the veto does not apply in deciding to convene a General Conference. Once a large majority of member-states adopts a revised “Second Charter” and ratify it, the choice for some opposing powers will be stark – to accept the Second Charter, or to remain outside the UN. Either choice does not preserve the veto. Nobody is bigger and more important than the entire world, and if someone decides to stay outside the UN, it won’t be the world that will suffer, rather that isolated member-state.

The General Conference and the elimination of the veto will open the doors wide as to all other excellent proposals for reforms, including the composition of the Security Council itself. It is astonishing how many UN member-states discuss the composition of the Council, but avoid mentioning the elimination of the veto. All talks about enlarging the Security Council, possible new permanent members, better representation of the Global South etc. are futile, if the veto remains and a single permanent member can easily erase all these efforts.

Art. 109 General Conference and a revised Second Charter can discuss and codify all other excellent proposals:

- World Parliamentary Assembly, to reflect population size, and add the voice of people, in addition of the voice of governments, in global governance. This will also create a better power balance between the principal organs of the UN.

- Add a new fourth pillar and purpose – to save the future generations from climate and environmental disasters – into the existing three purposes of the UN: peace and security, sustainable development and human rights.

- Address afresh issues of disarmament and arms control, including nuclear threats.

- Better financing to allow sufficient resources to support the purposes of the UN.

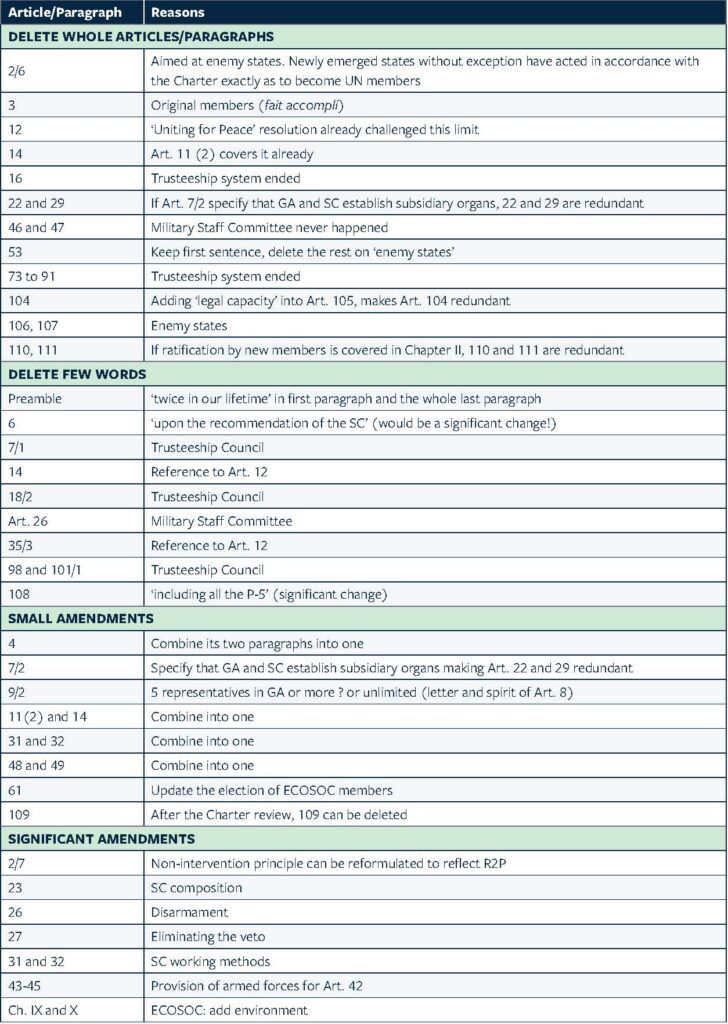

The academic work towards a Second Charter has already begun, under the aegis of the Global Governance Forum.17“A Second Charter: Imagining a Renewed United Nations”, Global Governance Forum, https://globalgovernanceforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/SecondCharter_Imagining-Renewed-United-Nations.pdf Below are specific suggestions for changes in the UN Charter and the reasons for these changes:

About the Author

Vesselin Popovski is Professor and Vice Dean of the Jindal Global Law School, and Founding Executive Director of the Centre for the Study of the United Nations at O.P. Jindal Global University in India. In 2004-2014 Senior Academic Officer and Head of “Peace and Governance Programme” at the UN University in Tokyo. Prior to that Legal Expert for the EU Project “Legal Protection of Individual Rights” in Russia; Assistant Professor at Exeter University in the UK; and Bulgarian diplomat. PhD from King’s College London; MSc from London School of Economics; BA and MA from Moscow State Institute of International Affairs (MGIMO). Published over twenty books and numerous articles in peer-reviewed journals.

Notes

- 1Guardian, 23 February 2023, Russian invasion ‘an affront’, says UN chief, as assembly meets on Ukraine. Accessed https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/feb/23/un-chief-condemns-russian-invasion-ukraine-united-nations-assembly-vote-peace-motion

- 2UN News, 27 February 2023, Human Rights Council: Russia responsible for ‘widespread death and destruction’ in Ukraine. Accessed https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/02/1133927

- 3SC/15172 from 12 February 2023 at https://press.un.org/en/2023/sc15172.doc.htm

- 4In Larger Freedom: Towards Development, Security and Human Rights for All: Report of the Secretary-General – United Nations and the Rule of Law. United Nations and the Rule of Law. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://www.un.org/ruleoflaw/blog/document/in-larger-freedom-towards-development-security-and-human-rights-for-all-report-of-the-secretary-general/.

- 5Popovski, Vesselin, “Innovating the Principal Organs of the United Nations”, in Willian Durch, Joris Larik, Richard Ponzio (eds) Just Security in an Undergoverned World ( Oxford UP 2018)

- 6https://electthecouncil.org/

- 7Popovski, Vesselin. “Towards Multiple Security Councils.” UN75 Global Governance Innovation Perspectives. Stimson Center. June, 2020. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://www.stimson.org/2020/js2020-towards-multiple-security-councils/.

- 8Guterres, António. Our Common Agenda: Report of the Secretary-General. September 2021. Accessed December 15, 2022.

https://www.un.org/en/content/common-agenda-report/assets/pdf/Common_Agenda_Report_English.pdf. - 9Ibid.

- 10Guterres, Our Common Agenda, 77.

- 11A/77/CRP.1 from 7 February 2023

- 12Ibid., 60–66.

- 13“Ukraine’s President Calls on Security Council to Act for Peace, or ‘Dissolve’ Itself.” UN News. April 5, 2022. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/04/1115632.

- 14Simma, Bruno (and others) The Charter of the United Nations: Commentary 3rd ed. Oxford UP 2012 P. 18

- 15Rao, K. Krishna. “The General Conference for the Review of the Charter of the United Nations.” Fordham Law Review, vol. 24, no. 3, Autumn, 1955, pp. 356-368.

- 16Ibid, p. 367

- 17“A Second Charter: Imagining a Renewed United Nations”, Global Governance Forum, https://globalgovernanceforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/SecondCharter_Imagining-Renewed-United-Nations.pdf