Executive Summary

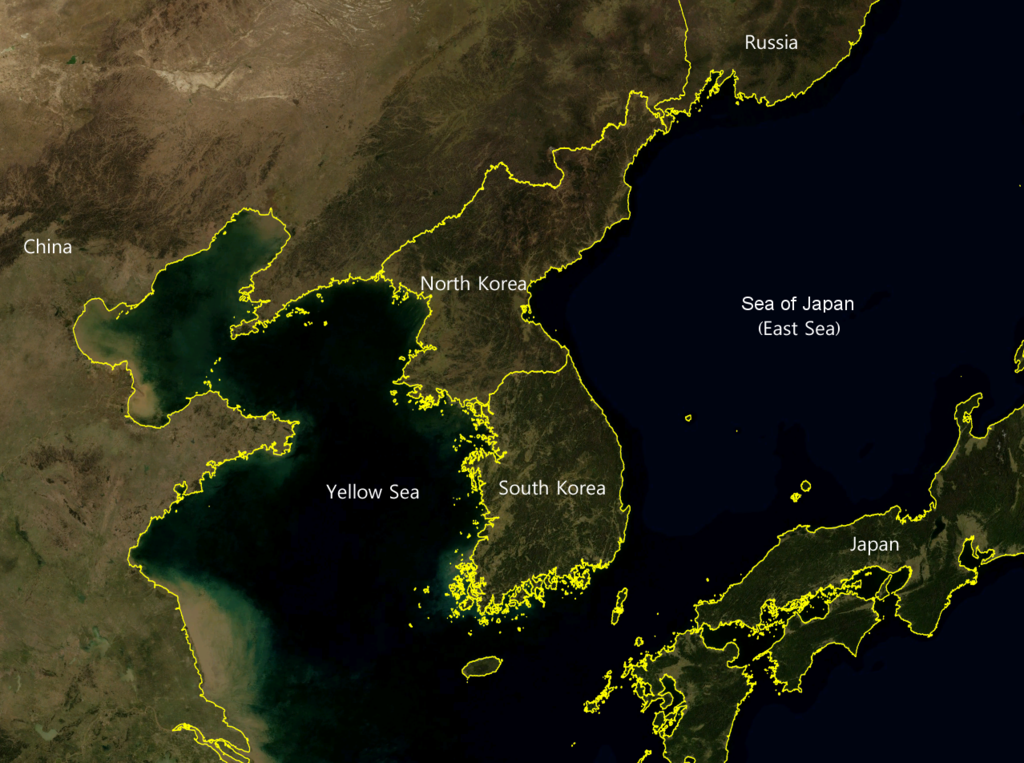

In 2019-2020, the Stimson Center’s 38 North and Security for a New Century (SNC) programs convened a bipartisan congressional Korea Study Group (KSG). The KSG brought U.S. House and Senate staffers together with a broad range of former U.S. and Republic of Korea (ROK) officials, analysts, and academics. The goal was to empower the U.S. Congress and to encourage its members to play their constitutional roles in key foreign policy and national security issues by building a dialogue that would consider security challenges on the Korean peninsula and surrounding region, explore options to prevent a wider conflict, reduce the chances of a nuclear exchange, and maintain U.S. security interests and alliances. While staff came from different offices, political parties, and viewpoints, this report highlights areas of convergence. Drawing on these meetings, the following main points and options emerged from our discussions:

- Increase Diplomacy on Nuclear Issues. Increasing diplomatic efforts to better understand what North Korea is willing to relinquish is necessary, even if there is significant skepticism that North Korea will agree to full denuclearization for the foreseeable future. Also, it is important to balance diplomacy with realistic and credible deterrence.

- Start with a Testing Moratorium. Securing a formal moratorium on nuclear and missile-testing has value, since it prevents further advancement of DPRK systems and could build toward diplomatic progress in other areas.

- Support the Executive Branch. Provide the executive branch greater flexibility and support effective negotiations if U.S.-DPRK negotiations were to move forward, by underwriting the effort through a “Sense of Congress” resolution in support of certain tension reduction measures, such as the inter-Korean Comprehensive Military Agreement (CMA).

- Work Across Committees. Critically examining Congress’s committee structure, wherein defense and diplomacy are the purview of separate committees, would be effective in learning how to balance both sides of the equation and maintain oversight that is mutually reinforcing.

- Build Parliamentary Connections. Creating regular, targeted, and systematic connections between the U.S. Congress and the ROK National Assembly, while building upon existing congressional delegations (CODELS) would help congressional and National Assembly committees, staffers, and lawmakers from all sides better understand one another’s geopolitical perspectives and political and decision-making systems.

- Address Cost-Sharing in the Region. Quickly concluding a three- to five-year Special Measures Agreement (SMA) deal and returning cost-sharing talks to the working-level would prove constructive. Additionally, creating a new consultative mechanism to operationalize ongoing discussions more formally on the ROK-U.S. alliance’s role vis-à-vis the U.S. Indo-Pacific Strategy and ROK’s New Southern Strategy, respectively, would be helpful.

- Transform the Alliance. Increasing the number of hearings and discussions with the U.S. military and the U.S. Department of State and the U.S. Department of Defense around the issue of alliance transformation and wartime Operational Control (OPCON) transfer is necessary. Discussions need to be held now to clear up misunderstandings and help policymakers and the American public better understand what OPCON transfer means for U.S. foreign policy and military force commitments overseas.

Introduction

The dilemma posed by North Korea’s nuclear weapons program is not new. Due to events over the last several years, dealing with this challenge has become more complicated for the U.S., its allies in the region, and the international community. From 2017 to 2020, the world witnessed brinkmanship and the threat of war on and around the Korean Peninsula followed by a sudden turn toward historic, yet unsuccessful, diplomacy. Despite such diplomatic efforts and amidst COVID-19, Pyongyang continues to develop its nuclear and missile forces and conventional capabilities. Moreover, the U.S.-ROK alliance has been strained in recent years by doubts over U.S. credibility, lack of consultation, overly politicized cost-sharing disputes, and divergent threat perceptions in a rapidly evolving strategic environment. These factors all highlight a security environment that is uncertain, unpredictable, and potentially exceedingly unstable.

Congress holds an essential role in addressing these issues and defining parameters of executive action. As we have seen in the past, Congress can support or become an obstacle to the implementation of any U.S.- North Korea agreements on denuclearization, normalization of relations, and sanctions relief. Through official Congressional Delegations (CODELS), inter-parliamentary engagement, and supportive resolutions, Congress can signal support for allies and enhance people-to-people ties by channeling the views of the broader public to our allies. Congressional appropriation of funds for the defense of South Korea has significantly impacted U.S. military forces’ capacity to maintain robust deterrence against hostile North Korean acts short of war in a deteriorating security environment or in an environment in which relations improve and tensions decrease. Also, difficulties in cost- and burden-sharing talks between the U.S. and South Korea can negatively affect U.S. congressional perceptions that Seoul is doing its fair share and could have a significant impact on the solidarity of the U.S.-ROK alliance.

To help Congress play its constitutional role in key foreign policy and national security issues, particularly as it relates to the Korean peninsula, the Stimson Center’s 38 North and Security for a New Century (SNC) programs convened a bipartisan congressional Korea Study Group (KSG) from February to December 2020. The KSG brought together House and Senate staff along with a broad range of former U.S. and ROK officials, analysts, and academics (all of whom are hereafter referred to as “participants”) to discuss a series of key issues related to peace and security on the Korean Peninsula. The following is a summary of some of the KSG’s more consequential themes and recommendations.

Managing A Nuclear North Korea

The most urgent challenges the KSG considered were North Korea’s nuclear program, its development of advanced missile capabilities, and the DPRK’s potential for proliferation, instability, and conflict on and around the Korean Peninsula. The KSG determined that strengthening diplomacy is the best option for addressing these challenges and that diplomatic efforts must be bolstered by realistic and credible deterrence.

Strengthening Deterrence

The KSG noted that while North Korea does not threaten the U.S. in the same way as it does South Korea and Japan, its ability to do so will continue to grow and undermine U.S. extended deterrence over time. Moreover, North Korea has shown greater interest in the development of asymmetric capabilities needed to deter a U.S. attack. Furthermore, despite punishing international sanctions and COVID-related restrictions, North Korea recently revealed an impressive array of new conventional assets, challenging standard assumptions that its conventional capabilities are mostly stagnant and outdated.

The U.S. and U.S.-ROK alliance has anticipated these threats for decades and has worked to stay ahead of them. However, since North Korea passed the nuclear threshold and continues to develop its asymmetric capabilities, U.S.-ROK defense posture and the strategy and practice of deterrence may need to adapt accordingly.

Participants in the KSG noted that North Korea’s stockpile continues to grow beyond the minimum needed for nuclear deterrence. Along with its pursuit of submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) capabilities, the DPRK buildup suggests its ambitions to develop second-strike capabilities and be recognized as a regional power. While the current overall deterrence posture remains favorable to the U.S. and its alliance partners, the 2018 National Defense Strategy Commission Review explained that should a crisis emerge on the peninsula, the U.S. may not have the ability to contain a conflict and defeat North Korea on conventional terms without risking escalation to a nuclear exchange as a result of how capabilities are organized and how underexamined nuclear escalation scenarios for the Korean peninsula have been.1National Defense Strategy Commission, “Providing for the Common Defense: The Assessment and Recommendations of the National Defense Strategy Commission,” United States Institute of Peace, November 13, 2018, https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/2018-11/providing-for-the-common-defense.pdf. Recent developments in DPRK missile technology also demonstrate that the regime has the capabilities to strike ROK targets with greater effectiveness and to evade missile defenses.

The KSG observed that if North Korea continues its development of nuclear capacities or engages in military provocations, the U.S. and alliance deterrence architecture would change significantly. If the U.S. diplomatic and military response is insufficient or severely wanting, Seoul and Tokyo could develop nuclear capabilities of their own. The latter would act as a vote of no confidence in Washington and undermine East Asian alliances on a fundamental level. Although such an extreme scenario is unlikely, emerging debates in Seoul and Tokyo about these issues demonstrate how U.S. credibility has come into doubt over the last decade.

KSG participants said that discordant responses to North Korea’s short- versus long-range missile tests reinforced a notion of threats “over there” versus threats to the U.S. mainland. Coupled with an overly transactional U.S. approach to alliance management in recent years, South Korean and Japanese anxieties have raised serious concerns about decoupling in the region. Seoul also questions if Washington would launch a nuclear strike without its consultation or even consent. To repair trust and promote greater trilateral coordination, the U.S. should consider what South Korea wants out of an alliance while working to ensure U.S. policies align with South Korean and Japanese policies and goals.

The U.S. does not want its allies to develop independent strike capabilities, which would heighten the risk of the U.S. being drawn into a foreign war. Beyond North Korea, global nuclear nonproliferation is also important when considering potential proliferation among U.S. allies. South Korea currently has limits on the payload and ranges of its missile capabilities based on U.S.-ROK missile guidelines, a bilateral agreement originally established in 1979. Although these guidelines have gradually loosened over the years, most recently in 2020, the U.S. does not provide South Korea with certain weapons technology. Japan has similar rules, which have considerably slowed the country’s weapons development.

If the United States does not reassure South Korea and Japan of its commitment to their military and political alliance, the KSG expressed concerns that those allies would shift away from the United States and pursue their own capacities. South Korea and Japan could seek more advanced conventional missile strike capabilities through indigenous development and foreign purchases; U.S. companies would lobby to sell them such weapons; and both would bristle at Washington’s attempt to restrict them—especially if they perceive the U.S. alliance commitment as lacking credibility. In this context, the KSG determined that South Korea’s tendency to see itself as a second-rate ally compared to U.S.-European relations—or even at times U.S.-Japan relations—and its desire for a seat at the table to make strategic decisions need to be addressed. Seoul will continue to call for deeper consultations. For its part, Seoul will need to offer greater strategic clarity on the role it is willing to play in regional collective security.

Approaches to Diplomacy with North Korea

When it comes to negotiations with Pyongyang, understanding the North Korean regime is crucial. The consensus among KSG participants was that the regime either will not or is unlikely to agree to total denuclearization or that North Korea is not currently ready to do so. KSG participants also noted that North Korean officials approach talks with a firm and cohesive strength of purpose, which makes compromise difficult. The U.S. and its allies do not bring the same cohesive front to the talks. Although the limits of what North Korea is willing to accept are not clearly understood, increased engagement can foster greater understanding. The Singapore (2018) and Hanoi (2019) summits showed that the regime is willing to place some limitations on its programs. In Hanoi, for instance, when Kim Jong Un offered up the Yongbyon Nuclear Scientific Research Center, where the bulk of North Korea’s fissile material production takes place, it appeared to signal North Korea’s willingness to accept certain quantitative restrictions on its arsenal. This may be a good starting point for future dialogue.

KSG participants differed over the efficacy of the Complete, Verifiable, and Irreversible Denuclearization (CVID) or Final Fully Verifiable Denuclearization (FFVD) formulas. Some argued it must be maintained, others stated that it was counterproductive. In either case, the consensus was that denuclearization should be the overriding goal of U.S.-DPRK talks, especially when it comes to signaling the importance of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).2Unlike other nuclear-weapons states (NWS), North Korea is the only country that was once a party to the NPT that withdrew and developed a nuclear weapons program. There was also consensus that any deal must lay out a clear roadmap based on simultaneous actions by both sides. Officials noted that in the beginning, negotiations should focus on smaller agreements, such as incremental arms control concessions, which can be reached more quickly. However, framing it as an arms control approach should be avoided to maintain the integrity of the NPT.

There was also agreement that the U.S. could seek a formal missile moratorium agreement with North Korea. Such an agreement could start by requiring clarification on what is and is not allowed as well as arranging a moratorium on explosive nuclear testing. An agreement could start with provisions that the U.S. is able to monitor externally and, after further negotiations, the conditions could be expanded to include a moratorium on large rocket motor testing, which are less detectable. However, an agreement that progresses in this way will inevitably become harder to verify externally and unilaterally, even with explicit verification measures specified.

KSG participants felt that maintaining U.S. and international sanctions early on during talks is essential, but adding more sanctions would not be helpful. While sanctions are the usual reaction of the U.S. to DPRK nuclear or weapons developments, their impact is limited and, in some ways, has diminished over time. Ultimately, to work, sanctions need stronger UN implementation, and member states need to comply with and enforce them. Simply adding more restrictions does not improve implementation. Diplomacy, improvements to the deterrence architecture, and export controls all need to occur simultaneously for progress to be made on denuclearization.

Concerning Congress’s role in North Korea policy and talks, the KSG noted that its tendency is to move toward sanctions that limit the president’s flexibility, which is necessary for effective negotiations. Although currently at a standstill, if U.S.-DPRK negotiations were to move forward, Congress could underwrite the effort by passing a non-binding, “Sense of Congress” resolution in support of certain tension reduction measures, such as the inter-Korean Comprehensive Military Agreement (CMA).3A “Sense of Congress” resolution is a non-binding joint resolution. This resolution sends a supportive signal but otherwise carries no legislative weight. However, it is more effective than a stand-alone “Sense of the House” or “Sense of the Senate” resolution passed by only one of the two chambers. In addition, Congress should focus more on allied diplomacy in negotiations, taking South Korea’s goals into consideration when designing North Korea policy. Lastly, as noted above, a successful strategy encompasses both defense and diplomacy. However, Congress’ committee structure places defense and diplomacy under the purview of separate committees. One KSG participant encouraged more critical dialogue on how the committees could balance both and maintain effective oversight that is mutually reinforcing rather than working at cross-purposes.

Finally, behind the KSG’s discussion was a more fundamental question about the mismatch between how the United States and North Korea approach talks. The U.S. consistently stresses the need for action (i.e., denuclearization), followed by trust, and then by relationship building. Whereas, culturally speaking, building a relationship is often the most important first step for the North Koreans. Some participants observed that the longstanding hostile relationship and the state of suspended war represented by the Korean War Armistice, makes it necessary to find a new way forward. An end of war declaration provides one possible avenue toward relationship building and an important step forward from an entirely military construct to more of a political one. Such an approach would also allow greater inclusion for and insight from South Korea and help to provide a new role for the United Nations Command (UNC), which would be instrumental in implementing the physical military changes that are crucial for a new relationship. Such a declaration would only prove useful if it were included as one among the other steps in a clearly defined roadmap and not as a one-off gesture.

Missile Defense and the Korean Peninsula

The KSG examined North Korea’s various missile threats, U.S. and allied missile defense assets and systems on and around the peninsula, and the wider strategic context.

DPRK Capabilities

Regarding short-range missiles, Pyongyang conducted over 30 tests in 2019-2020, indicating it sees these systems as battlefield weapons with validated performance and reliability parameters. Also, the tests have taken flight paths, which could possibly exploit an altitude gap between alliance and U.S. lower-tier and upper-tier missile defenses. Some gaps could be filled by tying in U.S. and ROK missile defense radars together to be more fully, technically integrated.

In regard to the development of North Korea’s SLBM capability, the KSG determined that many challenges remain. Pyongyang has certainly focused on this capability with a number of tests, both on land and at sea. Yet questions remain about its solid-propellant capabilities and the performance of their longer-range systems. While the SLBMs North Korea has tested so far fly somewhere between 1,500-2,000 km, and two more larger models have been displayed in recent military parades, there are doubts about their reliability and accuracy.

A key factor moving forward is whether or not the DPRK can develop enough operationally viable ballistic missile submarines, which is unlikely in the next five years, especially given that North Korea has been building a new ballistic missile submarine (only its second ever) for more than two years already and there is no indication of when it might be launched. Developing such a capability would give Pyongyang a 360-degree threat if they operated submarines south of the DMZ. Nevertheless, North Korea understands that U.S. anti-submarine warfare capabilities are far superior to and would likely neutralize anything it deploys during a conflict.

Contrary to its approach to short-range missiles, Pyongyang has not followed a similar testing approach with its Hwasong-14 and Hwasong-15 intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) or Hwasong-12 intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM). The lack of flight testing for these longer-range missile systems raises questions about their accuracy and reliability, particularly when compared to the development pattern of equivalent missiles in other countries. Moreover, North Korea has yet to demonstrate a workable reentry vehicle. Nonetheless, U.S. and allied policymakers must treat the DPRK long-range capability as valid and dependable and conduct defense planning as if these weapons are perfectly capable.

U.S. and Alliance Capabilities

The DPRK’s self-proclaimed moratorium on long-range missile testing and nuclear tests has served U.S. and allied interests significantly by postponing further advancements of its long-range systems. However, the Biden administration and Congress must be attuned to recent signals from Pyongyang, which announced it has lifted its suspension on testing as it rolled out enhanced missile assets during recent military parades, implying that they may test these new systems. This reinforces the need for diplomacy to negotiate a formal moratorium on missile testing.

Diplomacy notwithstanding, ROK and U.S. air and missile defense systems, including Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD), Patriot missiles, and the Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) System Standard Missile–3 (SM-3), offer substantial capability relative to DPRK missiles. In terms of capacity (i.e., quantity), Pyongyang would be able to overwhelm U.S. and ROK defenses in South Korea with large salvos of hundreds of missiles and, with artillery added, thousands of projectiles. The problem is further exacerbated by North Korea’s potential use of chemical, biological, or nuclear weapons. Yet, in such a scenario, a U.S. president maintains the capability to retaliate, potentially to the nuclear level, which reinforces deterrence. Bolstering deterrence requires denying objectives and putting sufficient doubt in the adversary’s mind regarding whether an attack would succeed to the extent desired, not to mention imposing significant costs with swift retaliation if an attack occurred.

U.S. and allied defenses are “point defenses” (e.g., defending key targets, such as command and control nodes and bases) rather than full-coverage, airtight defenses. While air-tight defense is infeasible, the U.S. and ROK should develop the capacity to defeat as much of those threats as possible in case a conflict were to occur, which means further integrating the peninsula’s missile defense, counterforce strategies, and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities while encouraging the exploration of directed energy systems (i.e., high-powered microwaves) to take out guided missiles when they are still within the Earth’s atmosphere (early boost phase). KSG participants felt Congress should pick up this issue going forward, and that the Biden administration should include it in all future Missile Defense Reviews.

Allied Coordination and Wider Context

KSG participants cited the importance of coordination between and among allies. Bilateral U.S.-ROK and U.S.-Japan coordination, respectively, has historically been quite good. The U.S. has integrated its ability to fire its own Patriot and THAAD on the peninsula, which results in a higher ability to handle salvos and conserve missiles. However, it is unclear if ROK Patriots are integrated. The ROK Korea Air and Missile Defense (KAMD) system is the core for missile defense on the peninsula, which the U.S. augments and enhances with its Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (C4ISR) capabilities and with the missile defense assets it brings to bear, namely, THAAD and Patriot Advanced Capacity–3 missiles (PAC-3). The U.S. and Japan Aegis Missile Defense systems are not currently integrated, but there has been and continues to be significant shared training and communication; Tokyo formally joined the U.S. regional system in 2006.

The KSG determined that Japan’s decision to suspend Aegis Ashore deployments was a mistake, however, they suggested this was something the U.S. should try to resolve as the U.S. relies on Japan’s participation in the system to help control costs. Moreover, trilateral integration is insufficient. Despite Washington’s efforts, historical enmity between Seoul and Tokyo, along with Seoul’s concerns about retribution from Beijing, continue to block anything approaching true regional integration. The Biden administration and Congress should put greater emphasis on improving trilateral relations in general and on bolstering a more cohesive, regional missile defense network in particular.

Noting the wider importance of missile defense operations beyond the peninsula, the KSG highlighted the fact that there is not a zero-sum or clear bifurcation between North Korea’s long-range or regional and short-range missile threats. In addressing both intercontinental and regional threats, the U.S. protects two core national security interests, namely, preventing a catastrophic attack on U.S. soil and providing for secure and reliable allies. The latter requires constant and clear public and private assurances, which was too often taken for granted by past administrations in Washington. One KSG participant encouraged that if U.S. officials are not tired of providing assurances, they are not providing enough. Also, having a strong national missile defense actually makes the U.S. more likely to protect its allies because it results in a lower chance of a successful blowback strike on the U.S. mainland. This strength should make allies more confident that the United States will defend them because it can defend itself.

With the last point in mind, the KSG considered the Trump administration’s decision to terminate the Redesigned Kill Vehicle (RKV) program—a long-running effort to replace the kill vehicles on the tips of the older Ground-Based Interceptors (GBI)—as inadvisable. The termination exacerbated the gap between existing U.S. missile defense capabilities and the DPRK missile threat. Washington should spend the resources necessary to develop new systems, such as the Next Generation Interceptor (NGI), in order to stay ahead of the North Korean ICBM threat, and support the improvement of the existing interceptors, kill vehicles as well as sensors, until the NGI is operational, most likely in the late 2020s.

Also, Japan’s suspension of the Aegis Ashore Ballistic Missile Defense System, raises larger questions about the role that regional assets can play as an underlay to the national missile defense system, meaning an added layer of protection against ICBM threats to the U.S. homeland.4Mike Yeo, “Japan Suspends Aegis Ashore Deployment, Pointing to Cost and Technical Issues,” Defense News, June 15, 2020, https://www.defensenews.com/global/asia-pacific/2020/06/15/japan-suspends-aegis-ashore-deployment-pointing-to-cost-and-technical-issues/. The KSG felt the question of underlay for the U.S. is an important one for Congress to examine, with the lowest cost option not being Aegis Ashore but the ability to tie SM-3 Block IIA interceptors into the national missile defense architecture. In the event of a severe crisis with North Korea wherein it launched missiles, if the United States military found that the GBI, or down the road, the NGI, did not have the capability or the capacity to do the full job, people would ask why the United States government did not look at this underlay option.

Lastly, the KSG stressed how the executive and Congress must be aware of the effect of these developments on strategic stability vis-à-vis China and Russia. U.S. messaging should be clear and consistent with past Nuclear Posture Reviews and Missile Defense Reviews. Specifically, the U.S. is building theater and regional systems capable of defeating Chinese and Russian missiles and will do the best it can, but it is building a national missile defense system to defeat so-called rogue states, particularly North Korea and Iran. Of course, if either China or Russia launched a missile at the U.S., the United States would try to intercept it. However, the U.S. is not building its national missile defense system to defeat Chinese or Russian capabilities. It has neither the capacity nor the capability to do so. Instead, missile defense against Beijing and Moscow rests on nuclear deterrence.

U.S. Indo-Pacific Allies in the Shadow of U.S.-China Strategic Rivalry

Since the KSG’s discussions repeatedly touched on wider interests, participants decided to assess how U.S. alliances fit within an increasingly confrontational U.S.-China relationship, situating current developments in a decade-long process. At the beginning of the Obama administration, U.S. policy toward China differentiated between areas of cooperation—such as joining the U.S.-led economic system or combatting climate change—and areas of competition. That began to shift during the second term of the Obama administration, with U.S. policy moving more toward competition. The Trump administration eagerly picked up this competition approach, as seen through its wide-ranging tariffs, National Security Strategy, and National Defense Strategy. Currently, there is a bipartisan consensus in Washington that China has been challenging U.S. interests in Asia and that a strategic response is needed.

The KSG felt the United States’ response to China’s role has been lacking in many ways. During the Obama administration’s “pivot” toward Asia, the administration’s attention was divided among other major issues from Russia to the Middle East. Later, the Trump administration’s economic, political, and diplomatic policies were overshadowed by its military response. One such example was U.S. military exercises in the South China Sea, which though essential, is less effective without accompanying political and diplomatic pressure.5Lara Jakes, “With Beijing’s Military Nearby, U.S. Sends Two Aircraft Carriers to South China Sea,” The New York Times, July 4, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/04/us/politics/south-china-sea-aircraft-carrier.html. The KSG felt the U.S. should better pay greater attention to the region as well as better incorporate its allies and partners in its Indo-Pacific strategy. Unfortunately, while refocusing U.S. attention on China, the Trump administration adopted an inconsistent attitude toward close allies like Japan and South Korea, including sending mixed signals regarding the credibility of its military commitments alongside exorbitant cost-sharing demands.

Moreover, the KSG felt the U.S. approach to China is too ideologically and politically driven. Instead, Washington needs to take an adaptable, well-defined approach that allows for cooperation on some issues and strategic competition in others. North Korea is one issue where both countries have some shared goals and values. Growing conflict between the two powers will undermine their ability to find common ground on North Korea, lead to economic costs for individual countries, and destabilize the region. Furthermore, recognizing China’s importance in dealing with North Korea, South Korea could lean toward China on some issues, especially when trying to improve inter-Korean relations.

Therefore, the KSG felt that to persuade allies in the region to follow its lead, Washington should give strategic priority to the Indo-Pacific. This approach should also increase the multilateral involvement of allies in security and diplomatic, and economic forums, especially to counter China’s Belt and Road Initiative. The U.S. should robustly plan and coordinate with its allies in terms of collective defense. Congress can build upon and refine existing legislation, such as the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act (ARIA), the Pacific Deterrence Initiative, and the Strategic Act.

Taken together, such legislation boosts and makes more credible U.S. deterrence against China, enhances budgetary transparency and congressional oversight of Pentagon funds, refocuses resources on key capability gaps, and reassures allies and partners. It also properly frames U.S.-China relations in terms of a longer-term strategy that includes not only military competition but also economic norms, democratic values and, importantly, prioritizes areas of cooperation such as arms control, North Korea, and the environment.

In terms of regional U.S.-ROK military cooperation, KSG participants noted that South Korea’s deterrence initiatives are aimed not only at North Korea but at China as well. The ROK Navy’s Aegis destroyers and long-range patrol aircraft demonstrate Korean intentions to deter China and conduct overseas long-range operations. To a lesser extent, the ROK Air Force and Army Special Forces are also capable of such missions. Barriers to off-peninsula cooperation include the shrinking size of the ROK military and underprepared reserves as well as the need to confront a more advanced DPRK conventional threat than previously thought.

Participants in the KSG agreed that as part of the strategic competition, the U.S. should also go on the offensive in regaining its soft power in the region through non-military means. Public opinion in the region has been shifting in favor of Chinese investments and contributions to the region, so a multilateral effort to encourage greater private investment alongside diplomatic outreach is needed. Instead of adopting an overly confrontational approach presented as a negation of Chinese efforts, the U.S. should reframe its strategy in terms of the positive values it upholds. Recent efforts by the U.S. and ROK to connect and promote cooperation between the Indo-Pacific strategy and the New Southern Policy provides a foundation on which to build. The Biden administration should work to further operationalize such cooperation.

Among KSG participants, the consensus was that there are few scenarios where South Korea would choose China over the United States. While by some metrics China’s economy is on track to surpass that of the U.S., the United States still has significant military and technological advantages. Also, Beijing’s values do not align with Seoul’s democratic system. It bears repeating that South Korea views the U.S. as its one and only ally, and that its long and conflictual history with China has led to deep distrust. Certainly, differences in culture and perspective can result in misunderstandings between the United States and South Korea. However, this only underscores the need for greater communication and consultation between Washington and Seoul and finding more tailored ways to align the alliance with US national strategies.

Differing geostrategic realities call for a nuanced appreciation for the other country’s positions and strategic empathy. Shared objectives should be emphasized as should an understanding that the two countries may have different preferred approaches to realizing their common goals. This more nuanced appreciation would help managers affectively align their efforts in a complementary manner.

Cost-Sharing: More Than Just Dollars and Cents

The KSG examined how the Trump administration’s approach to alliance cost-sharing represented a significant change from previous negotiations in terms of the amount the administration demanded from Seoul, the discordant tone of its demands, the highly politicized and unorthodox negotiating process, and the mixed signals the administration sent to both allies and adversaries.

The last Special Measures Agreement (SMA) expired in 2018. The Trump administration did not initiate the latest round of alliance cost-sharing talks until late 2019, months behind schedule, and left the White House in January 2021 without having settled on a new SMA. Due to President Trump’s direct intervention, negotiations moved out of the U.S. State Department and the regularized, working-level process—which had previously been just one aspect of alliance management—instead became highly politicized. The KSG felt Washington should move past this prolonged stalemate quickly and, with Congress’ support, conclude a new three- to five-year agreement, consistent with past practice.

The KSG drew several important insights from the Trump years that should guide cost- and burden-sharing talks in the future. Fair and equitable burden-sharing should take a more accurate assessment of ROK contributions, encompassing the whole structure of the alliance and recognizing Seoul’s unique security environment. The KSG observed that Trump’s rhetoric and demands were so exorbitant as to distort the public and lawmakers’ understanding of Seoul’s contributions within the SMA structure (e.g., covering nearly 50% of the labor, logistics, and construction costs for U.S. bases in South Korea), significant financial contributions for the construction of U.S. Army Garrison Humphreys (e.g., 90% of the cost), in addition to contributing considerable amounts toward ROK defense and military preparedness. Moreover, when it comes to cost-sharing, Seoul is often unfavorably compared with Tokyo. Yet this misguided view discounts the many contributions Seoul makes to its own and alliance defense (proportionately speaking as a percent of GDP) and U.S. foreign policy historically; including far greater manpower and combat contributions than Japan has or is able to make.

Further, in an attempt to meet President Trump’s demands, U.S. negotiators insisted on including new categories in the SMA talks, such as the transportation of U.S. troops and equipment and training costs. KSG participants cited that the Trump administration wrongly framed such requests as an extension of the original three-category SMA structure. Although there is an appetite in both Washington and Seoul for broadening the burden-sharing discussion, this would require a new negotiating structure.

Fortunately, the alliance has a long history of creating new types of consultative mechanisms when legacy mechanisms no longer suit changed conditions. Therefore, the KSG felt that the Biden administration, with the support and oversight of the Congress, should formulate a two-track solution. The first track would maintain the regular, three-category SMA structure and return SMA negotiations to the working-level. The second track would consider new U.S. demands separately and require a new negotiating team and timeline to discuss different elements of burden-sharing in the alliance. These new tracks could be expanded to include ongoing discussions about the U.S.-ROK alliance and how it is nested within the U.S. Indo-Pacific Strategy and ROK’s New Southern Strategy, respectively.

Finally, KSG participants declared that the Trump administration’s approach to the US-ROK alliance was unrealistic and disruptive not only in the scope and nature of its demands, but also because it paid very little attention to South Korea’s domestic politics. Although there was widespread support for the alliance and U.S. military presence on the peninsula among the ROK public, majorities among all age and political cohorts opposed the exorbitant U.S. cost-sharing demands. The Moon administration in Seoul, faced with a U.S. demand so high as to be seen as illegitimate and that would also require National Assembly approval, felt no real pressure to meet it. Such dynamics posed several risks: undermining alliance trust and cohesion; erosion of support for the U.S. presence among the ROK public; a potential uptick in anti-American sentiment; growth, in turn, of negative American attitudes toward South Korea; and wider spillover effects, such as misperception and alliance divergence beyond the Korean Peninsula. And while the short-term risks to military readiness are low, such negative trends could influence the US-ROK military dimension in the longer term.

With these considerations in mind, the KSG highlighted that South Korea’s domestic politics are of greater importance to the U.S.-ROK alliance than ever before. It is unclear how these dynamics will play out, but it is clear that South Korean society faces increasing uncertainty about the long-term vision of the alliance. Consequently, there is a need for greater communication and consultation to address the misunderstandings borne of differences in culture and perspective. Therefore, the KSG calls for regular, targeted, and systematic linkages between the U.S. Congress and ROK National Assembly. Building upon existing Congressional Delegations (CODELS), the KSG encourages the establishment of consistent communication avenues between US Congress and ROK National Assembly staffers. The U.S. Senate and House Armed Services Committees should work to foster greater dialogue with the ROK’s National Defense Committee, and the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and House Foreign Affairs Committee should do the same with the ROK’s Foreign Affairs and Unification Committee. Such interactions would assist staffers and lawmakers on either side to better understand one another’s perspectives and political and decision-making systems.

Alliance Transformation and the Transfer of Wartime Operational Control (OPCON)

Throughout various KSG meetings, the issue of the wartime transfer of operational control (OPCON) from the U.S. back to South Korea repeatedly arose. While OPCON transfer is possible, many people still do not understand it, which could result in significant alliance discord. Therefore, the KSG examined the four theater-level military commands in South Korea and challenges surrounding OPCON transfer.

The KSG reviewed the four theater-level military commands operating concurrently on the Korean peninsula: the U.S. Forces Korea (USFK), an American unilateral command; the ROK Joint Chiefs of Staff (ROK JCS), a Korean unilateral command; the Combined Forces Command (CFC), a U.S.-ROK bilateral command; and the United Nations Command (UNC), an American-led multinational command. The same four-star U.S. general simultaneously commands the USFK, CFC, and UNC. He is “triple-hatted” across the three commands, despite their distinct imperatives and reporting channels. These theater-level commands have undergone several phases or evolutions since the Korean War, with changes in OPCON a central element in the process.

In particular, the KSG focused on the earlier U.S.-ROK alliance plan (2007-2013) to transfer wartime OPCON to Seoul by dissolving the CFC and instead create two parallel commands: a leading (e.g., supported) command operating under the ROK JCS and a re-designated USFK, Korea Command (KORCOM) supporting command, with an alliance liaison office or military committee providing strategic direction to them both. However, the KSG reviewed how due to strong opposition from both U.S. and ROK officials, this parallel construct was ultimately dropped in 2013. Instead, the alliance partners decided to maintain a combined command and moved toward a transition to a future-oriented, ROK-led CFC, with an ROK commander and U.S. deputy commander.

The current conditions-based wartime OPCON transfer plan, mutually agreed upon by both countries, requires that: (1) the ROK acquires the military and operational capability to lead the combined defense mechanism; (2) the ROK develops the capacity to initially counter North Korea’s nuclear and missile threats; and (3) that the security environment on and around the Korean Peninsula should be conducive to an OPCON transfer. Nonetheless, despite Washington and Seoul’s agreement on the three conditions, the KSG identified several challenges that lie ahead.

The Moon administration is eager to complete the wartime OPCON transfer before the end of its term in May 2022. However, Seoul appears to be pushing the certification process forward based on political rather than military calculations, which contravenes the conditions the allies mutually agreed upon in the process. This, in turn, has evoked pushback from U.S. officials. Seoul has also tried to maintain close ties with the U.S. so as to mitigate any security vacuum that might occur during the transfer and prevent having to take on more burden than it can bear, which potentially may arouse U.S. displeasure and produce the perception that South Korea is getting a free ride. Some KSG participants observed that Seoul appears to discount the strategic implications and collective security responsibilities that come with the OPCON transfer.

The KSG noted additional challenges coming from the U.S. side, particularly in how the United States perceives the issue of wartime OPCON transfer. After all, even while maintaining a combined construct, the future-oriented, ROK-led CFC would still result in a great power placing its force under the OPCON of a Korean commander. For many U.S. officials this is difficult to fathom. Historically, the U.S. has maintained a degree of control over the security environment in South Korea and has been very cautious about engaging in a major campaign on the peninsula unless it is worthwhile and in the national interest.

For some, the transfer of wartime OPCON raises questions about the U.S. ability to have the right controls in place to put the brakes on any escalating situation and that if a conflict ensues, U.S. forces would have their preferred leader in charge giving orders, guidance, and vision that most aligns with U.S. national interests. KSG participants also noted U.S. concerns regarding the potential institutional mismatch after wartime OPCON transfer between a still U.S.-led UNC, tasked with monitoring the armistice and integrating multinational forces, and a more assertive ROK JCS. Lastly, divergent threat perceptions between the allies vis-à-vis North Korea must be more fully and transparently explored before OPCON transfer can be executed.

In sum, the KSG felt that both ROK and U.S. officials perpetuate misunderstandings regarding the actual mechanics of the military command architecture, which could result in significant disagreement if left unattended. The KSG determined that these challenges require greater attention from the executive branch, Congress, and within the alliance. Congress should increase hearings and discussions with the U.S. military and the U.S. Departments of State and Defense around the issue of alliance transformation and OPCON transfer. Discussions need to be held now to dispel misunderstandings and in turn, help policymakers and the American public better understand what OPCON transfer means for U.S. foreign policy and force commitments overseas.

Recommendations for the Biden Administration and 117th Congress

The KSG determined that diplomacy remains the best option when dealing with North Korea. For diplomacy to succeed, however, the Biden administration and Congress must link negotiations with a strengthened and credible deterrence posture and enhanced cohesion in the U.S.-ROK alliance.

Although policymakers are skeptical regarding North Korea’s willingness to agree to full denuclearization and reticent to pursue a cap-and-freeze approach to its programs, securing a formal moratorium on the North’s nuclear and missiletesting as a first step has value, since it prevents further advancement of DPRK systems and could build toward diplomatic progress in other areas. Consistent with such an approach, Congress can offer the executive branch greater flexibility and support effective negotiations by underwriting the effort through a “Sense of Congress” resolution in support of certain tension reduction measures, such as the inter-Korean Comprehensive Military Agreement (CMA).

When it comes to the U.S.-ROK alliance, the Biden administration should quickly conclude a three-to five-year SMA deal and return cost-sharing talks to the working-level to help rebuild some trust in the alliance. Additionally, in order to address broader burden sharing concerns and achieve greater cohesion amidst a rapidly shifting strategic environment, the administration should create a new consultative mechanism to more formally operationalize linkages between the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy and ROK’s New Southern Strategy. Also, in the context of alliance transformation and the transfer of wartime OPCON to South Korea, the administration must explore new and deeper forms of consultation with Seoul regarding U.S. deterrence and military strategies in the region.

Greater consultation in these areas will enhance deterrence in relation to a growing and evolving North Korean threat and bolster diplomacy with a more cohesive front. Relatedly, the administration must address how a discordant U.S. response to North Korea’s short- versus long-range missile tests has reinforced the notion of threats “over there” versus threats to the U.S. mainland. This mindset has increased South Korean and Japanese anxieties about decoupling in the region, and undermined U.S. credibility. To repair trust and promote greater trilateral coordination, the U.S. needs to consider what South Korea wants out of the alliance while working to ensure U.S. policies align with South Korean and Japanese policies and goals.

Congress can complement the administration’s effort to improve alliance management and trust by endeavoring to create regular, targeted, and systematic linkages with the ROK National Assembly. Lawmakers can build upon existing congressional CODELS by establishing more regular communication mechanisms between congressional and National Assembly committees and their staffers. Such interaction would help staffers and lawmakers on both sides of the Pacific better understand one another’s geopolitical perspectives and political and decision-making systems.

Lastly, Congress should increase hearings and discussions with the U.S. military and the U.S. Departments of State and Defense around the issue of alliance transformation and OPCON transfer. Discussions need to be held now to clear up misunderstandings and help policymakers and the American public better understand what the OPCON transfer means for U.S. foreign policy and military commitments overseas.

In closing, the KSG encourages both the Biden administration and the U.S. Congress to increase their consultations with allies and to enhance their strategic thinking about how the U.S.-ROK alliance can and should evolve in relation to a changing regional threat environment and alliance maturation.

Annex

About the Korea Study Group

In 2019-2020, the Stimson Center’s 38 North and Security for a New Century (SNC) programs convened a bipartisan congressional Korea Study Group (KSG). The KSG brought together staffers from both the House and Senate along with a broad range of former U.S. and Republic of Korea (ROK) officials, analysts, and academics. The goal was to empower Congress to play its constitutional role in key foreign policy and national security issues and build a dialogue to consider security challenges on and around the Korean Peninsula, explore options to prevent a wider conflict, reduce the chances of a nuclear exchange, and to maintain U.S. security interests and alliances. While staff came from different offices, political parties, and viewpoints, the KSG sought out areas of convergence where possible.

Numerous Hill staff attended Stimson’s KSG sessions. However, among them was a regular cohort of staffers whose individual members served on the Senate Committees on Foreign Relations, Armed Services, and Intelligence, the House Committees on Foreign Affairs and Armed Services, or were members of the Congressional Caucus on Korea and Congressional Study Group on Korea. The regular cohort also included professional staff members (PSMs) assigned to both the majority and minority sides on the foregoing committees, with emphasis on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee’s East Asia, The Pacific, and International Cybersecurity Policy Subcommittee and the House Foreign Affairs Committee’s Asia, the Pacific, Central Asia and Nonproliferation Subcommittee. Expert analysts from the Congressional Research Service (CRS) also regularly attended the KSG sessions. At a time of great debate and partisanship, finding consensus was often difficult. Furthermore, the virtual nature of most of our events inhibited our ability to foster informal ties. Nevertheless, the KSG sought to foster greater dialogue as a key step toward seeking a baseline of agreement. The repeated attendance of a regular cohort at the KSG sessions demonstrated the strength of our approach.

All KSG sessions were held on a not-for-attribution basis. Stimson Fellow Clint Work was the key facilitator of the KSG, and was supported by Stimson Vice President Victoria Holt, 38 North Deputy Director Jenny Town, and Research Assistant Iliana Ragnone.

KSG Event List

- February 11, 2020: U.S.-ROK Alternative Futures Out-Briefing; Rayburn House Office Building

- March 4, 2020: Sanctions and the DPRK’s Public Health Infrastructure; Dirksen Senate Office Building

- April 24, 2020: U.S. Alliances in the Indo-Pacific; Zoom Webinar

- April 29, 2020: The U.S.-South Korea Alliance and Ongoing Cost-Sharing Talks; Zoom Webinar

- June 18, 2020: Missile Defense Futures and the Korean Peninsula; Zoom Webinar

- July 29, 2020: U.S. Indo-Pacific Allies in the Shadow of U.S.-China Strategic Rivalry; Zoom Webinar

- September 4, 2020: U.S.-ROK Alliance Transformation and Wartime Operational Control (OPCON); Zoom Webinar

- September 16, 2020: UN Panel of Experts Midterm Report: North Korea’s WMD Programs; Zoom Webinar

- September 22, 2020: Managing Nuclear Risks with North Korea; Zoom Webinar

- December 17, 2020: The Implications of the 2020 Election: Views From Seoul; Zoom Webinar

About the Author

Clint Work is a Fellow with the Stimson Center, appointed to its Security for a New Century and 38 North programs: Clint leads congressional engagement on Korean peace and security issues and engages in various research projects centered on the U.S.-ROK alliance and U.S.-DPRK relations. Prior to joining Stimson, he was an assistant professor at the University of Utah’s Asia Campus in South Korea and the regular foreign policy writer for The Diplomat Magazine’s Koreas page. He holds a Doctorate in International Studies from the University of Washington and a Master’s in International Relations from the University of Chicago. In addition to his academic publications, he has written extensively for popular media, including the Washington Post, Foreign Policy, The Diplomat Magazine, The National Interest, 38 North, and Sino-NK.

The Stimson Center

The Stimson Center promotes international security, shared prosperity & justice through applied research and independent analysis, deep engagement, and policy innovation.

For three decades, Stimson has been a leading voice on urgent global issues. Founded in the twilight years of the Cold War, the Stimson Center pioneered practical new steps toward stability and security in an uncertain world. Today, as changes in power and technology usher in a challenging new era, Stimson is at the forefront: Engaging new voices, generating innovative ideas and analysis, and building solutions to promote international security, prosperity, and justice.

More at www.stimson.org.

Security for a New Century (SNC)

Security for a New Century (SNC) is a Congressional education and outreach program of the Stimson Center that fosters non-partisan, not-for-attribution dialogue around international security challenges—principally via study group sessions for Hill staff. SNC focuses on organizing impactful briefings and sessions that strengthen Congressional knowledge and potential for action on the most urgent security threats to our country and world, and builds space for engagement. SNC offers a unique and neutral environment for Members and their staff to receive factual information and analysis, provided in an atmosphere of learning and constructive problem-solving. For 2020, Congressional Fellows were Clint Work and Carolyn Haggis, supported by Vice President Victoria Holt and Research Associate Alex Hopkins.

38 North

38 North, a program of the Stimson Center, was founded by Joel Wit and Jenny Town in 2010 and has since successfully built and maintained a reputation of providing accurate and authoritative policy and technical analysis related to North Korea, covering a wide range of topics including the North’s WMD programs and economic development. The project’s main objective is to provide careful, well-informed and well-reasoned analysis to government officials, the media, and the interested public.

Acknowledgements

KSG programming was made possible by generous support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the Open Society Policy Center.

Notes

- 1National Defense Strategy Commission, “Providing for the Common Defense: The Assessment and Recommendations of the National Defense Strategy Commission,” United States Institute of Peace, November 13, 2018, https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/2018-11/providing-for-the-common-defense.pdf.

- 2Unlike other nuclear-weapons states (NWS), North Korea is the only country that was once a party to the NPT that withdrew and developed a nuclear weapons program.

- 3A “Sense of Congress” resolution is a non-binding joint resolution. This resolution sends a supportive signal but otherwise carries no legislative weight. However, it is more effective than a stand-alone “Sense of the House” or “Sense of the Senate” resolution passed by only one of the two chambers.

- 4Mike Yeo, “Japan Suspends Aegis Ashore Deployment, Pointing to Cost and Technical Issues,” Defense News, June 15, 2020, https://www.defensenews.com/global/asia-pacific/2020/06/15/japan-suspends-aegis-ashore-deployment-pointing-to-cost-and-technical-issues/.

- 5Lara Jakes, “With Beijing’s Military Nearby, U.S. Sends Two Aircraft Carriers to South China Sea,” The New York Times, July 4, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/04/us/politics/south-china-sea-aircraft-carrier.html.