Introduction

At the June 2022 Madrid Summit, NATO Allies declared the “…centrality of Human Security and… ensuring that Human Security principles are integrated into our three core tasks.”1Note: “Madrid Summit Declaration Issued by NATO Heads of State and Government (2022),” NATO, June 29, 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_196951.htm. In addition, they noted, “We are advancing a robust Women, Peace and Security agenda, and are incorporating gender perspectives across NATO.” The subsequent Strategic Concept mentions Human Security (HS) and Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) as core principles: “We will promote…Human Security and the Women, Peace, and Security agenda across all our tasks.”2Note: “NATO 2022 Strategic Concept” (NATO, June 29, 2022), https://www.nato.int/strategic-concept/. In late October 2022, NATO released the Human Security Approach and Guiding Principles.3Note: NATO, “Human Security – Approach and Guiding Principles,” NATO, October 14, 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_208515.htm.

Yet, with this impressive policy and conceptual work, there is still little general knowledge or agreement on what HS and WPS mean in practice for future military operations and how they work with, or, as some claim, against each other.4Note: The research in this paper is based on the author’s personal experience spanning more than a decade including as a US Army Engineer and Civil Affairs officer, a NATO, US, UN, and Folke Bernadotte Academy trained Gender Advisor, a non-resident instructor at the Nordic Center for Gender in Military Operation, as well as a Gender Advisor to: Commander of the US European Command, the US Military Representative to the Military Committee at NATO, the Head of the NATO Committee on Gender Perspectives, and the US Agency for International Development. The author also conducted eleven expert interviews with both WPS and HS experts and seven individuals provided critical opinions and guidance to an early draft of the paper. The Alliance is at a critical juncture where the focus should be on clarifying and defining how HS can be operationalized in a way that contributes to NATO missions and operations. The WPS experience can impart essential lessons.

There is also a need to articulate and agree upon how the WPS and HS frameworks will “complement and reinforce each other, across all core tasks,”5Note: NATO, “Human Security – Approach and Guiding Principles,” para. 9. as mentioned in the HS approach.6Note: In this paper we talk about Human Security and the Protection of Civilians. These are two separate concepts and we do not use the terms interchangeably. When we discuss HS, we mean the concept as released in early November 2022. When we talk about PoC we mean the 2016 policy and follow-on documents. Practical discussions should explore the two sides of this issue: driving future work by placing the WPS agenda under the umbrella of HS and maintaining WPS’s stand-alone position to implement the two in a parallel manner.

History of Human Security and Women, Peace, & Security

The international Human Security (HS) concept significantly predates Women, Peace, and Security. The United Nations Development Programme’s 1994 Human Development Report introduced the then-new concept of Human Security: “[It] equates security with people rather than territories, with development rather than arms. It examines both the national and the global concerns of Human Security.”7Note: “Human Development Report 1994” (United Nations Development Programme, July 7, 1994), https://www.undp.org/publications/human-development-report-1994.Canada introduced HS at the UN General Assembly (UNGA) in 1994 and convened a panel to define it. Later UNGA resolutions defined Human Security and its value in supporting the UN’s mission: “That [it] is an approach to assist Member States in identifying and addressing widespread and cross-cutting challenges to the survival, livelihood, and dignity of their people.”8Note: “General Assembly Resolution 66/290” (United Nations General Assembly, September 10, 2012), https://www.unocha.org/sites/dms/HSU/Publications%20and%20Products/GA%20Resolutions%20and%20Debate%20Summaries/GA%20Resolutions.pdf.

According to the UN, ensuring that decisions are people-centered, comprehensive, context-specific, and prevention-oriented leads to HS. Human Security is thus focused on human beings and should be continuously considered.9Note: Annick T.R. Wibben, “Human Security: Toward an Opening,” Security Dialogue 39, no. 4 (August 2008): 455–62, https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010608094039. Interestingly, the justification for military intervention during the war in the Balkans in the 1990s was Human Security, emphasizing the Responsibility to Protect.10Note: Alan J. Kuperman, “The Moral Hazard of Humanitarian Intervention: Lessons from the Balkans,” International Studies Quarterly 52, no. 1 (2008): 49–80, http://www.jstor.org/stable/29734224. While HS has no UN Security Council resolutions, it is an essential normative framework. As UNGA defined it, Human Security is a nation-state responsibility that spans the continuum of good governance.

Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) was first acknowledged by UNSCR 1325, adopted in 2000, and then subsequent resolutions—10 in total—all focusing explicitly on the intersection of how women, children, and other marginalized groups experience conflict.11Note: “Security Council Resolution 1325” (United Nations, October 31, 2000), https://peacemaker.un.org/sites/peacemaker.un.org/files/SC_ResolutionWomenPeaceSecurity_SRES1325%282000%29%28english_0.pdf; Gina Heathcote, “Security Council Resolution 2242 on Women, Peace and Security: Progressive Gains or Dangerous Development?,” Global Society 32, no. 4 (October 2, 2018): 374–94, https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2018.1494140. As the UN defines WPS, this agenda is achieved through four main approaches: protection, prevention, participation, and access to relief and recovery. It focuses on how these groups experience conflict and how decision-makers should consider their needs throughout a crisis or conflict.12Note: “Security Council Resolution 1325.” NATO has done substantially more work integrating the principles of WPS into its mission than with HS.13Note: Megan Bastick and Claire Duncanson, “Agents of Change? Gender Advisors in NATO Militaries,” International Peacekeeping 25, no. 4 (2018): 554–77; Matthew Hurley, “Watermelons and Weddings: Making Women, Peace and Security ‘Relevant’ at NATO through (Re) Telling Stories of Success,” Global Society 32, no. 4 (2018): 436–56; Katharine A.M. Wright, “NATO’S Adoption of UNSCR 1325 on Women, Peace and Security: Making the Agenda a Reality,” International Political Science Review 37, no. 3 (2016): 350–61; Katharine A.M. Wright, Matthew Hurley, and Jesus Ignacio Gil Ruiz, NATO, Gender and the Military: Women Organising from Within (Routledge, 2019). It has policies, strategies, training, and education within the Alliance that supports this approach and application, as well as a department head with the Nordic Center for Gender in Military Operations.14Note: Diana Morais, Samantha Turner, and Katharine A.M. Wright, “The Future of Women, Peace, and Security at NATO,” Transatlantic Policy Quarterly, August 22, 2022, http://transatlanticpolicy.com/article/1146/the-future-of-women-peace-and-security-at-nato. While NATO has started this critical work on HS and made strides in the various cross-cutting topics (CCTs), more work remains to fully realize the approach’s intent and underpinning policies.15Note: Anonymous Interviewee #5, WPS and Human Security, interview by Samantha Turner, December 1, 2022. The 2022 Strategic Concept and the new HS Approach and Guiding Principles provide the impetus for this future work.16Note: NATO, “Human Security – Approach and Guiding Principles”; “NATO 2022 Strategic Concept.”

Concerns About the Adoption of Human Security

Before NATO developed the HS approach, political leaders loosely conceptualized Human Security as a group of critical CCTs for the Alliance, including the protection of civilians (PoC), preventing and responding to conflict-related sexual and gender-based violence (CR-SGBV), combating trafficking in human beings (CTHB), children and armed conflict (CAAC), and cultural property protection (CPP).17Note: Anonymous Interviewee #2, WPS and Human Security, interview by Samantha Turner, November 14, 2022. NATO’s new Human Security Approach is meant to organize and house the CCTs in a way that makes sense for the Alliance and its mission and better integrates into NATO’s values-based leadership role in the future of warfare.

There is an opportunity for the WPS and HS communities,18Note: For this paper, when we refer to WPS or HS communities we mean the group of people working on WPS and HS in and around NATO, mostly at the operational and tactical levels. as well as other experts who work on specific CCTs, to come together, share lessons identified from the implementation of these agendas over the past years, key in on the normative frameworks established for each discipline, and move into the future aiming to be truly mutually supporting in their approaches.

Based on interviews with WPS and HS community experts, some have concerns about how NATO can implement the Human Security approach. The WPS and PoC agendas within NATO already have 10-15 years of development behind them and are formally housed under the Military Contribution to Peace discipline. While work remains to implement these topics fully, they must have an institutional home and oversight. CAAC has no discipline yet, but the Civil-Military Cooperation Centre of Excellence ensures that PoC and CAAC are introduced in their courses.

When public talk of NATO adopting a Human Security approach first surfaced in 2017-18, the reception was lukewarm, particularly among PoC advocates, many of whom had worked with NATO on PoC for over a decade.19Note: Turner, Samantha, and Anonymous Interviewee #5. WPS and Human Security, Personal, 1 December 2022. At first, PoC advocates pushed back against the concept, mainly as HS was not defined for NATO as PoC had been in the Alliance’s 2016 policy.20Note: NATO, “NATO Policy for the Protection of Civilians Endorsed by the Heads of State and Government Participating in the Meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Warsaw,” NATO, July 9, 2016, http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_133945.htm. POC advocates saw HS as unnecessarily duplicating and displacing the PoC policy, which already included the CCTs. It was unclear how HS would affect PoC implementation, which had, until then, been the focus of NATO. However, soon it became clear that Human Security would become the primary approach with PoC as one of the CCTs under it. Once Allies reached a political consensus on HS, advocates followed suit, shifted focus, and adjusted their work plans and strategies.

The WPS community, civil society, military practitioners, and those that steward the Women, Peace, and Security agenda for NATO also had concerns.21Note: Anonymous Interviewee #2, WPS and Human Security. Several interviewees told us that one concern with the Human Security Approach is that the progress of the WPS agenda movement will be stalled, usurped, or defunded.22Note: Anonymous Interviewee #3, WPS and Human Security, interview by Samantha Turner, November 10, 2022. Much of the community’s progress on the WPS agenda, including developing a baseline understanding among organizations and commanders to take gender advisors seriously and dedicate time and resources to them, was hard-fought. Our research has shown that by gathering all “nontraditional” security topics under one “umbrella,” some in the community have concerns that Human Security may obscure that progress, confuse partners and allies, and take time and resources away from efforts to integrate a gender perspective.23Note: Anonymous Interviewee #4, WPS and Human Security, interview by Samantha Turner, November 9, 2022. Interviewees highlighted evidence that WPS and HS may become reduced to a staff function rather than mainstreamed and leveraged where it can maximize the benefit to missions.24Note: Ibid.

Structurally, practitioners are worried that gender advisors may morph into “Human Security advisors” and be expected to advise across all topics.25Note: Anonymous Interviewee #3, WPS and Human Security. Practitioners from WPS and across the CCTs agree that expecting advisors to be experts in gender, conflict-related sexual violence, human trafficking, protection of civilians and children, and cultural property protection is unrealistic. Some practitioners have shared feedback from UN missions where child protection and gender advisors were combined in one role. This approach results in the individual leaning on their strength and the secondary topic not getting the attention it needs in a mission, increasing risk to the mission and security outcomes. In other words, it does not work.26Note: Anonymous Interviewee #2, WPS and Human Security.

There is also concern that HS is being used because some commanders and military personnel seem to shut down when they hear the word “women” or do not think it applies to them. There is a school of thought that the word “women” and the concept of gender in an advisor’s title sets up an unnecessary conflict.27Note: Anonymous Interviewee #3, WPS and Human Security. So the question arises, should NATO place WPS under Human Security organizationally? It would not be the first organization or State to do so; the United Kingdom has experimented with placing WPS and gender more broadly under the Human Security moniker that aims to put an “emphasis on the security of the people and their social and economic environment rather than focusing on security of the state.”28Note: United Kingdom Ministry of Defense: Army, “77th Brigade: Human Security,” accessed November 12, 2022, https://www.army.mod.uk/who-we-are/formations-divisions-brigades/6th-united-kingdom-division/77-brigade/human-security/. The UK has designated WPS as one of its vital cross-cutting themes for all aspects of Human Security, ensuring gender, understanding the human environment, population vulnerabilities, and threats are woven into the operational analysis. They leave the internal best practices as a task for everyone to implement in their diversity and inclusion strategies, driving projects to remove barriers from role specifications, mentoring women, and recruitment, among other things.29Note: Anonymous Interviewee #6, WPS and Human Security, interview by Samantha Turner, December 4, 2022. This has the additional outcome of removing the position title that includes the word “women” and seemingly singular focus on “gender,” potentially avoiding commanders’ pushback to advisors.

However, there are community concerns about this, too. Some view it as a missed opportunity to have “difficult conversations” with commanders otherwise dismissive of anything other than bullets and bombs.30Note: Anonymous Interviewee #1, WPS and Human Security, interview by Samantha Turner, November 29, 2022. Many practitioners in the community ask, “Why should we give leaders a pass here?” referring to the need for organizational and cultural change and difficult conversations challenging biases, existing cultures, and roles.31Note: Anonymous Interviewee #1, WPS and Human Security. Based on the author’s experience, continued resistance to WPS is primarily due to leadership’s lack of understanding and engagement with gender perspectives. In some cases, interviewees have also seen commanders assigned a gender advisor without the experience or expertise to articulate the value of gender perspectives in military operations fully. They can end up hurting WPS rather than demonstrating its value. Suppose NATO intends to keep up with the pace of modern war and the tools and techniques used against the Alliance. In that case, it needs to reflect and adapt, or its adversaries can—and will—weaponize their bias (even if unintentional) against it.

From a political leadership perspective, there is a concern about the future role and responsibilities of the Secretary General’s Special Representative for Women, Peace, and Security (SRSG).32Note: Anonymous Interviewee #3, WPS and Human Security. The position, identified as a best practice by UN Women,33Note: “Global Study on the Implementation of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325,” UN Women, 2015, https://wps.unwomen.org/. was developed to gain parity with the UN’s WPS representative and move the agenda forward within NATO. The post was meant to focus on and emphasize the outsized adverse effects war and conflict have on women and children’s agencies and to advise the Secretary General on how NATO should address these issues.34Note: Anonymous Interviewee #3, WPS and Human Security. If this position becomes the “SRSG for Human Security,” as some fear it will, they say the value it brings promoting the WPS agenda risks being diluted or lost.35Note: Anonymous Interviewee #2, WPS and Human Security.

Planning a Way Forward, Together

Many of the concerns we outlined above are based on the historical experience of interviewees who gave examples of the resistance, sidelining, and general misconceptions of this type of work, especially the addition of topics with a similar focus. However, we believe NATO can address these concerns systematically by moving forward on the implementation of the HS approach and that it should strengthen gender perspectives within the CCTs.

We identified several opportunities to support the implementation of a systemic and mutually reinforcing approach to HS and WPS.

Women, Peace, & Security

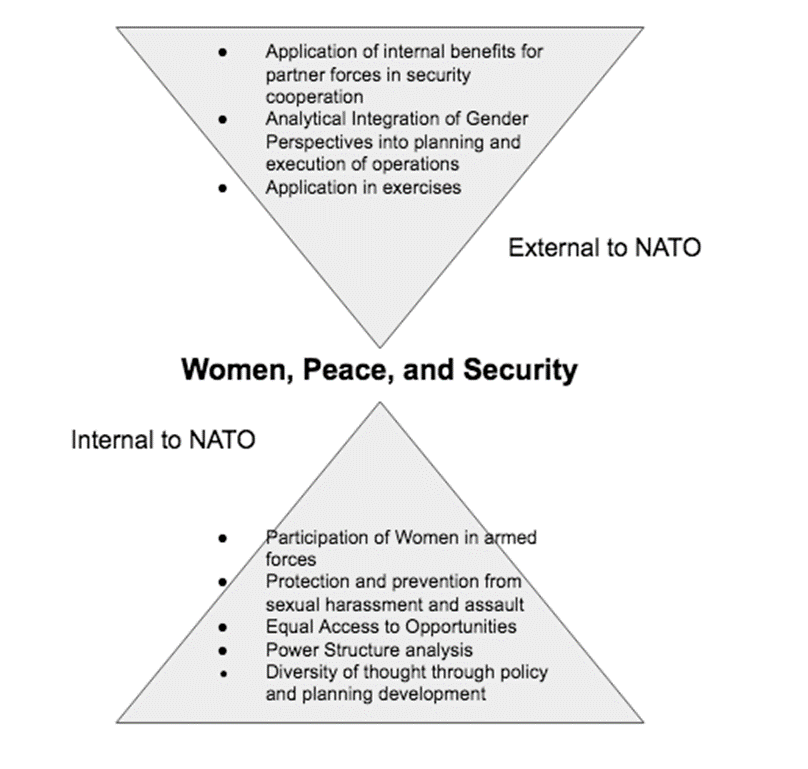

The 2022 Strategic Concept notes that NATO should integrate WPS across all the core tasks.36Note: “NATO 2022 Strategic Concept.” However, to succeed, it is necessary to articulate and reframe how it enhances and helps achieve the NATO mission set. This work clarifies that WPS is a library of best practices and an analytical tool. Some talk about the WPS agenda as best practices or an analytical tool, but the WPS community should distinguish the two to conceptualize and better describe its applied value. There are several ways to describe it, but one of the most common is the internal-external value model (visualized below) that shows how WPS principals can be applied internally to organizations (during peacetime) as well as externally to organizations (during peacetime with security cooperation and exercises, as well as during conflict through the integration of gender perspectives).

The application of best practice begins and ends with the expertise of gender advisors; we know the best gender advisors have a deep understanding of the WPS agenda in the military context:

- To encourage full and equal participation of women at all levels of decision-making within civilian and military structures.

- To incorporate gender perspectives and the participation of women in the prevention of conflict using root cause analysis and a comprehensive approach, from peace to violent conflict.

- To understand, know, and incorporate the specific protection needs of women and girls in conflict and post-conflict stabilization to include CRSV reporting.

- To ensure women’s equal access to humanitarian and international assistance and support the needs and capacities of women before, during, and after conflict.

Gender advisors should be able to articulate how all the above fit into the spectrum of operations and the value they bring during peacetime, cooperative security, crisis prevention, management, deterrence, and defense. This is one significant aspect of leveraging the WPS agenda.

However, the most powerful tool for applying WPS concepts is gender analysis and, as NATO calls it, the integration of gender perspectives. By this, we mean the ability to analytically, rapidly, and creatively assess the meaning of what one observes in the human environment and to use that knowledge to make sound recommendations that will have real effects on the operation to the commander. The community can assist when those gendered aspects aren’t as straightforward because there will be gendered aspects for all CCTs.

Therefore, there are analytical benefits to integrating gender perspectives into all of NATO’s HS topics as an enhancement and using gender advisors as a resource for the equitable rollout and implementation of more robust HS topics. And there are research-proven ways WPS principles can help strengthen the Alliance and Allies in peacetime, planning and programming with partners. WPS can bring value everywhere, whether it is the best practice application of diversity, equity, and inclusion within organizations showing that increasing the balance of men and women improves organizational outcomes37Note: Wei Wei Liu et al., “Women in the Workplace” (McKinsey & Company, October 18, 2022), https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/diversity-and-inclusion/women-in-the-workplace. or considering how intelligence assessments are strengthened when the entirety of the human environment is included.38Note: Based on the author’s lived experience demonstrated in more than seven different major US and NATO exercises; there is no public, unclassified research at this time on this topic.

Human Security

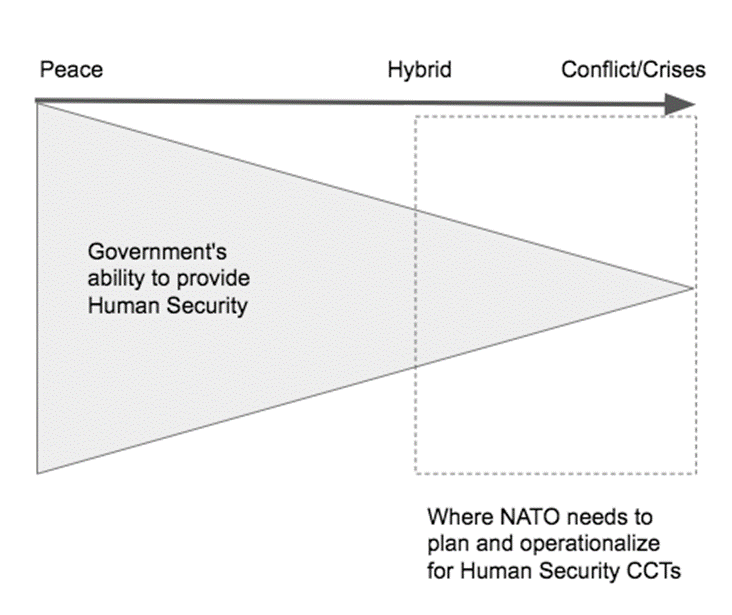

NATO should focus its HS work on clarifying what HS means in military operations and developing the capabilities and coordination needed to ensure that NATO is ready to “do” Human Security during conflict and crises. Human Security can and should be conceptualized as adding value to planning, exercise, and operational execution in future conflicts and crises. Human Security and its CCTs (Protection of Civilians [PoC], preventing and responding to conflict-related sexual violence [CRSV], combating trafficking in human beings [CTHB], children and armed conflict [CAAC], and cultural property protection [CPP]) “provide a heightened understanding of conflict and crisis. This [will allow] NATO to develop a more comprehensive view of the human environment, enhancing operational effectiveness and contributing to lasting peace and security.”39Note: NATO, “Human Security – Approach and Guiding Principles.” Therefore capabilities under each CCT (analytical and practical) should be developed across the Alliance to support mission success.

Among the CCTs, PoC is particularly important for the military, especially in conflict or crisis. It is currently the primary way the military contributes to Human Security. While many military tasks across the spectrum of NATO Staff functions contribute to PoC, articulating what critical tasks should be done when and in which specialties are crucial. An example of this is Understanding the Human Environment (UHE). While WPS must be integrated across all the CCTs, it is essential to ensure gender perspectives are considered in UHE and PoC.

Practical Solutions

In addition to ensuring that WPS and HS are mutually supporting, both HS and WPS communities need to start discussions on a road map of how NATO should “do” HS moving forward. There is a significant opportunity for the WPS and HS communities to shape their value propositions. There is not just one way to execute the rollout of the Human Security approach to best suit NATO. Some solutions involve an overhaul of existing structures and a robust build-out within the Alliance of military subject matter experts in each of the cross-cutting topics. However, the reality is that NATO may not have the human or financial resources to do this. Entire civil society sectors have expertise in these subjects, and our solutions keep some of these realities in mind. Additionally, there are lessons the WPS community has learned and community observations that can inform the process moving forward. We discuss some practical solutions below.

For NATO

NATO should maintain its implementation of the WPS Agenda, maintaining the existing Gender in Military Operations (GMO) discipline and the gender advisor structure. The value that a good gender advisor can bring a commander is significant and essential across all NATO core tasks. The best practice programmatic value that WPS brings across the continuum of conflict—from peace to war and everything in between—is a distinct enabler that should be shepherded through maintaining distinct WPS operationalization and programming from HQ to operational headquarters to tactical units on the ground. Keeping this discipline robust also will enable supporting Human Security with gender perspectives.

To operationalize Human Security, NATO should consider the following:

NATO should establish HS as a discipline. This would standardize and facilitate the implementation of Human Security as an approach to be applied across the Operational and Tactical levels. As HS is not currently a NATO Discipline, there is no formal way to build consensus around roles, responsibilities, training audience, and structure. As the discipline evolves, there should be a close collaboration with experts to develop doctrine and standards relating to every aspect of Human Security. This should include a comprehensive approach plan for coordinating with civil society experts to anticipate issues before they arise in crisis and conflict.

NATO should build out the structural network of HS focal points, functional specialists, and HS Liaisons. To coordinate HS concepts, NATO should identify, select, and train individuals to become HS focal points and functional specialists and develop liaison roles for general knowledge. As noted above, expecting one person to be the subject matter expert for the five topics under Human Security is unreasonable. Focal points would feed into the functional specialist and liaison work at higher levels. In certain functional areas, there is an acute need for military HS expertise; NATO should develop training and associated documentation to integrate HS concepts into planning, exercises, and real-time conflict and crises. The functional specialist in HS should take lessons from the HS and PoC communities and their deep experience with intelligence, targeting, and operational analysis in Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, and Libya. Developing an HS function specialty should focus heavily on PoC40Note: As NATO initially defined PoC in the 2016 policy, the CCTs were included, and they are naturally considered a part of protecting civilians in times of conflict.as the means and method to achieve HS. This approach would significantly increase how HS issues are thought about and addressed during the planning, exercises, and operational execution and encourage the development of standard operating procedures and policies within those specialties. Those receiving this training would not be experts in PoC or other HS topics but would serve as integrators across the operational planning process and provide this knowledge during exercises and operations. PoC is a fundamental aspect of HS in times of conflict and crisis.

NATO should develop and codify a formal liaison (LNO) capacity between allied military actors and vetted external HS topic experts. Regular peacetime exchanges with these experts will bolster service members’ understanding of the CCTs and enable them to recognize the expertise needed in a crisis or conflict. The military LNOs should be able to speak the same language as experts to communicate what analysis and advice are required to effectively transmit critical information to military decision-makers.

Allies should ask NATO to prioritize coordinated consultation plans with a group of POC and CCT experts to enable seamless cooperation during crises and conflicts. Close coordination with experts from civil society41Note: “Secretary General Appoints Group as Part of NATO Reflection Process,” NATO, March 31, 2020, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_174756.htm. can be a tremendous asset to the Alliance’s mission success during peacetime and conflict and crisis and for standardization of response to known security threats.42Note: “NATO starts work on Artificial Intelligence certification standard,” NATO, February 7, 2023, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/news_211498.html Establishing an Alliance-screened network of Human Security experts who can consult during peacetime or in crises—like the LNO model—could be the mechanism for coordination and cooperation to facilitate the “delivery” of HS where needed. To benefit from different experiences, expertise, and viewpoints, NATO should formalize this expert network by developing a process to draw from proven civil society organizations and independent experts. Understanding that these groups can be challenging to manage and keep meaningfully engaged, NATO should ensure their systematic integration into action plans associated with implementing the policies by tying their inclusion to deliverables, actively involving them in exercises as mentors, and staying up to date on the latest policies and procedures within NATO to help advise member nations on national training regimes. Before new crises or conflicts arise, NATO should do this now to encourage the rapid development of a custom and, if necessary, a rapidly available team of trusted experts.

Establishing an Alliance-screened network of Human Security experts who can consult during peacetime or in crises—like the LNO model—could be the mechanism for coordination and cooperation to facilitate the “delivery” of HS where needed. To benefit from different experiences, expertise, and viewpoints, NATO should formalize this expert network by developing a process to draw from proven civil society organizations and independent experts. Understanding that these groups can be challenging to manage and keep meaningfully engaged, NATO should ensure their systematic integration into action plans associated with implementing the policies by tying their inclusion to deliverables, actively involving them in exercises as mentors, and staying up to date on the latest policies and procedures within NATO to help advise member nations on national training regimes. Before new crises or conflicts arise, NATO should do this now to encourage the rapid development of a custom and, if necessary, a rapidly available team of trusted experts.

For NATO Stakeholders

Unity of Effort. It is essential that the WPS and HS communities embrace the concept of “unity of effort” and act fast to solidify an agreed-upon way forward as NATO implements the HS agenda. This moment is a critical opportunity, and we will be successful only if we establish the path ahead through consultation.

Engage Leadership. Both the WPS and HS communities must agree on the way forward, including by building community agreement on how HS fits into NATO’s mission and is operationalized. Experts from the military, civil society, and academia who have worked with or in NATO and these fields should together propose practical recommendations to political and military leadership.

Build Knowledge. The community should take the outcomes of these consultations, determine structure and training requirements, and identify a target audience to contribute to conversations about discipline establishment and HS structure. HS roles and training should be responsive to the community and build on the “how to” of implementing HS. Successful implementation must integrate or “mainstream” WPS into the CCTs.

Agree Upon Framework. The communities should work to develop a shared framework for when NATO does WPS and HS and where each program is essential for success. The framework should include an exercise integration guide with examples of injects, standard operating procedures, policies, and practices.

Build a Comprehensive Approach. This approach should include a broad range of stakeholders who have a role in crises and conflict when NATO responds. The comprehensive approach should welcome vetted experts with security clearances to round out NATO’s ability to integrate Human Security considerations into real-life crisis response and conflict management.

Conclusion

NATO’s Human Security approach is flexible enough to grow and change as security concerns evolve. This broad approach will enable NATO to integrate and frame future Human Security concerns as the Alliance deals with them. The recommendations put forward in this paper reflect a pragmatic approach to reframing the current narrative and finding solutions that address the WPS community’s concerns. It is critical to address these concerns strategically as civil society advocates continue to work closely with NATO to operationalize WPS and HS.

If not heeded, the warning signs unearthed in the research and discussed in this paper put NATO at risk of falling short of its aspirations for both WPS and HS. Beyond this, other challenges may postpone or even regress, implement, and progress for years. The most significant danger could come during an active conflict or crisis within NATO territory where disorganized or absent WPS and HS operationalization directly affects NATO citizens. Without consensus, compromise, and collective action, WPS and HS risk being sidelined as topics deemed unable to contribute to every aspect of NATO’s mission set. That is why it is so crucial that we quickly reach agreements as a WPS and HS community.

The way forward is to smartly fill out the HS approach and honor the WPS agenda together. This is a critical opportunity for all of us, and we should seize it to ensure we make this approach work for everyone, especially those it aims to inform and assist—NATO leadership.

Samantha Turner is the Senior Military Advisor to Stimson Center’s Strengthening NATO’s Ability to Protect Project and a Nonresident Fellow at the Center. She has more than a decade of expertise in gender in military operations and service as a U.S. Army officer.

The views expressed in this paper are the author’s and are informed by eight interviews with Women, Peace and Security, and Human Security experts. Pictured: NATO Battlegroup Latvia conducts urban operations training in 2019.

Notes

- 1Note: “Madrid Summit Declaration Issued by NATO Heads of State and Government (2022),” NATO, June 29, 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_196951.htm.

- 2Note: “NATO 2022 Strategic Concept” (NATO, June 29, 2022), https://www.nato.int/strategic-concept/.

- 3Note: NATO, “Human Security – Approach and Guiding Principles,” NATO, October 14, 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_208515.htm.

- 4Note: The research in this paper is based on the author’s personal experience spanning more than a decade including as a US Army Engineer and Civil Affairs officer, a NATO, US, UN, and Folke Bernadotte Academy trained Gender Advisor, a non-resident instructor at the Nordic Center for Gender in Military Operation, as well as a Gender Advisor to: Commander of the US European Command, the US Military Representative to the Military Committee at NATO, the Head of the NATO Committee on Gender Perspectives, and the US Agency for International Development. The author also conducted eleven expert interviews with both WPS and HS experts and seven individuals provided critical opinions and guidance to an early draft of the paper.

- 5Note: NATO, “Human Security – Approach and Guiding Principles,” para. 9.

- 6Note: In this paper we talk about Human Security and the Protection of Civilians. These are two separate concepts and we do not use the terms interchangeably. When we discuss HS, we mean the concept as released in early November 2022. When we talk about PoC we mean the 2016 policy and follow-on documents.

- 7Note: “Human Development Report 1994” (United Nations Development Programme, July 7, 1994), https://www.undp.org/publications/human-development-report-1994.

- 8Note: “General Assembly Resolution 66/290” (United Nations General Assembly, September 10, 2012), https://www.unocha.org/sites/dms/HSU/Publications%20and%20Products/GA%20Resolutions%20and%20Debate%20Summaries/GA%20Resolutions.pdf.

- 9Note: Annick T.R. Wibben, “Human Security: Toward an Opening,” Security Dialogue 39, no. 4 (August 2008): 455–62, https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010608094039.

- 10Note: Alan J. Kuperman, “The Moral Hazard of Humanitarian Intervention: Lessons from the Balkans,” International Studies Quarterly 52, no. 1 (2008): 49–80, http://www.jstor.org/stable/29734224.

- 11Note: “Security Council Resolution 1325” (United Nations, October 31, 2000), https://peacemaker.un.org/sites/peacemaker.un.org/files/SC_ResolutionWomenPeaceSecurity_SRES1325%282000%29%28english_0.pdf; Gina Heathcote, “Security Council Resolution 2242 on Women, Peace and Security: Progressive Gains or Dangerous Development?,” Global Society 32, no. 4 (October 2, 2018): 374–94, https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2018.1494140.

- 12Note: “Security Council Resolution 1325.”

- 13Note: Megan Bastick and Claire Duncanson, “Agents of Change? Gender Advisors in NATO Militaries,” International Peacekeeping 25, no. 4 (2018): 554–77; Matthew Hurley, “Watermelons and Weddings: Making Women, Peace and Security ‘Relevant’ at NATO through (Re) Telling Stories of Success,” Global Society 32, no. 4 (2018): 436–56; Katharine A.M. Wright, “NATO’S Adoption of UNSCR 1325 on Women, Peace and Security: Making the Agenda a Reality,” International Political Science Review 37, no. 3 (2016): 350–61; Katharine A.M. Wright, Matthew Hurley, and Jesus Ignacio Gil Ruiz, NATO, Gender and the Military: Women Organising from Within (Routledge, 2019).

- 14Note: Diana Morais, Samantha Turner, and Katharine A.M. Wright, “The Future of Women, Peace, and Security at NATO,” Transatlantic Policy Quarterly, August 22, 2022, http://transatlanticpolicy.com/article/1146/the-future-of-women-peace-and-security-at-nato.

- 15Note: Anonymous Interviewee #5, WPS and Human Security, interview by Samantha Turner, December 1, 2022.

- 16Note: NATO, “Human Security – Approach and Guiding Principles”; “NATO 2022 Strategic Concept.”

- 17Note: Anonymous Interviewee #2, WPS and Human Security, interview by Samantha Turner, November 14, 2022.

- 18Note: For this paper, when we refer to WPS or HS communities we mean the group of people working on WPS and HS in and around NATO, mostly at the operational and tactical levels.

- 19Note: Turner, Samantha, and Anonymous Interviewee #5. WPS and Human Security, Personal, 1 December 2022.

- 20Note: NATO, “NATO Policy for the Protection of Civilians Endorsed by the Heads of State and Government Participating in the Meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Warsaw,” NATO, July 9, 2016, http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_133945.htm.

- 21Note: Anonymous Interviewee #2, WPS and Human Security.

- 22Note: Anonymous Interviewee #3, WPS and Human Security, interview by Samantha Turner, November 10, 2022.

- 23Note: Anonymous Interviewee #4, WPS and Human Security, interview by Samantha Turner, November 9, 2022.

- 24Note: Ibid.

- 25Note: Anonymous Interviewee #3, WPS and Human Security.

- 26Note: Anonymous Interviewee #2, WPS and Human Security.

- 27Note: Anonymous Interviewee #3, WPS and Human Security.

- 28Note: United Kingdom Ministry of Defense: Army, “77th Brigade: Human Security,” accessed November 12, 2022, https://www.army.mod.uk/who-we-are/formations-divisions-brigades/6th-united-kingdom-division/77-brigade/human-security/.

- 29Note: Anonymous Interviewee #6, WPS and Human Security, interview by Samantha Turner, December 4, 2022.

- 30Note: Anonymous Interviewee #1, WPS and Human Security, interview by Samantha Turner, November 29, 2022.

- 31Note: Anonymous Interviewee #1, WPS and Human Security.

- 32Note: Anonymous Interviewee #3, WPS and Human Security.

- 33Note: “Global Study on the Implementation of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325,” UN Women, 2015, https://wps.unwomen.org/.

- 34Note: Anonymous Interviewee #3, WPS and Human Security.

- 35Note: Anonymous Interviewee #2, WPS and Human Security.

- 36Note: “NATO 2022 Strategic Concept.”

- 37Note: Wei Wei Liu et al., “Women in the Workplace” (McKinsey & Company, October 18, 2022), https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/diversity-and-inclusion/women-in-the-workplace.

- 38Note: Based on the author’s lived experience demonstrated in more than seven different major US and NATO exercises; there is no public, unclassified research at this time on this topic.

- 39Note: NATO, “Human Security – Approach and Guiding Principles.”

- 40Note: As NATO initially defined PoC in the 2016 policy, the CCTs were included, and they are naturally considered a part of protecting civilians in times of conflict.

- 41Note: “Secretary General Appoints Group as Part of NATO Reflection Process,” NATO, March 31, 2020, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_174756.htm.

- 42Note: “NATO starts work on Artificial Intelligence certification standard,” NATO, February 7, 2023, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/news_211498.html