By Pamela Kennedy

Two North Korean test missiles sailed over Hokkaido in August and September 2017, stirring anxiety in Japan. But after U.S. President Donald Trump mentioned the 1977 abduction of Japanese schoolgirl Megumi Yokota by North Korea in his first address to the U.N. General Assembly on September 19, attention returned to the rachi mondai, the abduction issue. Trump’s speech drew praise from the Abe administration, and Prime Minister Shinzo Abe reiterated on September 28 that the government of Japan (GOJ) is committed to resolving the issue.

However, the GOJ’s policy of prioritizing the abduction issue has historically put it at odds with other concerned nations in multilateral efforts to deal with North Korea. In the SixParty Talks, defunct since 2009, the Japanese delegation’s insistence on resolving the abductions before discussing strategic concerns, particularly denuclearization, contributed to Japan’s marginalization in the negotiations. The GOJ resorted to bilateral negotiations and meetings with North Korea, continuing through 2014, which yielded little satisfaction in spite of North Korea’s supposed investigation into the abductions.

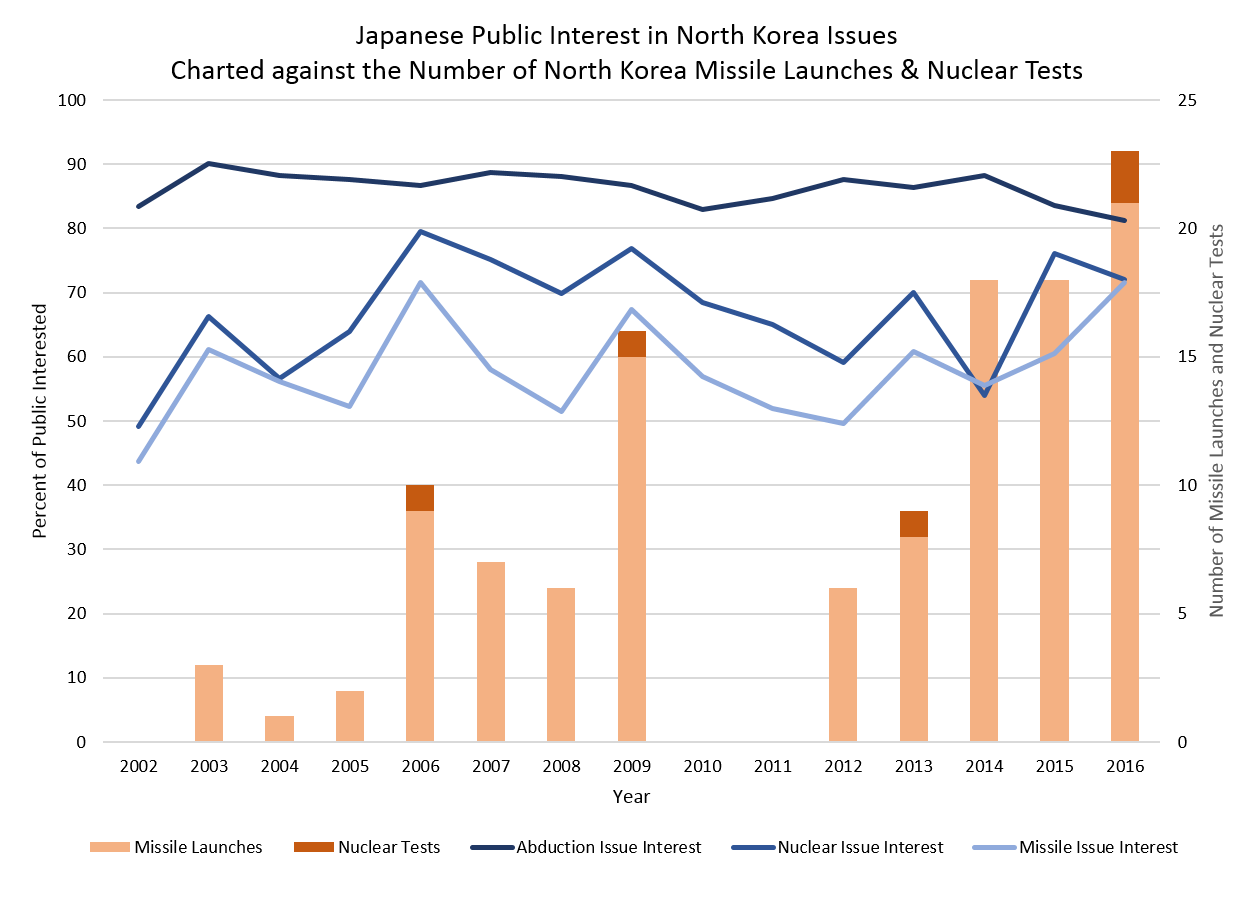

The GOJ’s policy is driven by intense public interest in the matter. Cabinet Office annual public opinion surveys have tracked the North Korea-related issues in which the public is interested since 2002, when Kim Jong-il admitted to some of the abductions during a visit with Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi. Subsequently, in the 2003 survey, 90.1% of citizens surveyed said that they were interested in the abductions, compared to less than 70% who were interested in nuclear and missile issues. At that time, the nuclear threat was distant, as North Korea did not conduct a nuclear test until 2006, and missile tests were infrequent. Since then, the abduction issue has remained the issue of greatest interest for the Japanese public in every survey, with the nuclear and missile issues consistently less of a concern (see chart). But as North Korea’s nuclear and missile tests have picked up pace and the threat to Japan has become more credible, interest in nuclear and missile issues have climbed to 72.1% and 71.5% respectively in October 2016, while the abduction issue has dropped to 81.2%, closing the gap somewhat.

Chart by author using poll data from Cabinet Office Public Opinion Surveys on Diplomacy, 2002-2016, and missile launches and nuclear test data from CSIS Missile Threat, North Korea Missile Launches, 1984-Present.

In response to North Korea’s threats, members of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) have proposed acquiring additional missile defense systems and the ability to strike enemy bases, in the event of repeated attacks from North Korea. Public opinion remains divided on any revisions or reinterpretations of the Constitution to give more leeway in defense capabilities, but some polls show support for Diet consideration of retaliatory strikes (58% support in April 2017, Yomiuri), while others indicate that support for international military action against North Korea is very low (14% in April 2017, Nikkei). But a willingness to explore additional defense options likely follows a heightened perception of threat from North Korea in recent years. According to a Yomiuri poll in May 2017, more of the public now prioritizes policies focusing on denuclearization (69%) and missile cessation (49%) than the resolution of the abductions (46%). In contrast, in Yomiuri’s May 2014 poll, the public wanted policies to address the abduction issue (66%) more than denuclearization (57%) or abandonment of missiles (33%). This indicates that while the abduction issue remains important to the Japanese public, policies to address immediate dangers are beginning to take priority at a time of increasingly credible threat. This shift in public opinion might give the GOJ more room to maneuver in talks with North Korea going forward.

Certainly, North Korea’s increasingly aggressive behavior in 2017, including two ICBM tests displaying an advancement in capabilities in July, and Trump’s belligerent statements towards North Korea and Kim Jong-un have ramped up tension in the region. In this situation, it is easy for the GOJ to work in solidarity with South Korea and the U.S. in opposing North Korea’s nuclear program and missile activity. But should the heat of the moment cool, as it has in the past, the GOJ may again be tempted to pursue the abduction issue more vigorously – particularly if the ICBMs are enough of a game-changer to make larger, strategic issues more difficult to negotiate. The GOJ has leverage with North Korea to offer in return for abductee information, after all: severe sanctions, such as those restricting money sent to North Korea and access to Japanese ports, the lifting of which North Korea has requested in past bilateral meetings.

The peril of this approach, however, is that in a calmer time the U.S. and South Korea would still prioritize the nuclear and missile issues and see a unilateral loosening of sanctions as a step in the wrong direction, especially if the sanctions are among those established by U.N. Security Council resolutions. If the U.S. and South Korea decide to pursue negotiations on other aspects of North Korea’s nuclear program, such as nonproliferation or international inspections, Japan may again find itself isolated – not a palatable option for LDP members who want to focus on security issues anyway. Even if South Korea were to implement a policy of dialogue and engagement, as President Moon Jae-in supported in his campaign, Japan’s inflexibility on the abduction issue would make coordination with South Korea extremely difficult. Moreover, North Korea is not known for keeping its end of a bargain and may offer to Japan information or people that it cannot or will not produce.

Considering these potential unwanted outcomes, while the difficulty of negotiation strategic issues with an ICBM-capable North Korea may create space for bargaining on the abduction issue, the GOJ should avoid the temptation to take such an opportunity. Instead, as North Korea continues to menace, public opinion will likely shift further in support of security solutions, giving the GOJ more flexibility in setting priorities and crafting a North Korea policy in coordination with the U.S. and South Korea. The question, then, is whether public opinion will change fast enough in the face of North Korea’s rapid progress.

____

Pamela Kennedy is a Research Associate with the East Asia program at Stimson.