Executive Summary

Overview

This report assesses the potential relationship between climate and environmental security and violence against civilians by different actors. The argument advanced is that the relationship between climatic stressors and environmental conditions is moderated: violence increases in climate-harsh regions — where incentives for violence over resources are higher — but only during months where environmental security levels are higher, which prompts armed actors to loot agricultural resources and use violence to this end.

Methods

The study relies on mixed methodology to assess these policy claims. Quantitatively, it employs a newly released, high-resolution geographic dataset to obtain descriptive evidence and to conduct a more rigorous statistical assessment using well-established econometric methods. Political violence data is taken from three widely used conflict databases and is assessed for both state and nonstate actors. The quantitative results are complemented by two qualitative case studies of Burkina Faso and northeastern Nigeria. These cases focus on the local dynamics of violence in these regions as they pertain to the policy framework advanced in the report.

Highlights

- Violence against civilians by both state and nonstate actors intensifies in Sahara transition zones (climate-harsh areas) during times of greater environmental security and agricultural resource abundance.

- Violence against civilians by all actors decreases in or is unchanged compared with the continental average within climate-harsh Sahara transition zones during times of lower environmental security and agricultural resource abundance.

- A distinction between environmental conditions and climate stressors is illustrated to be especially valid for preventive political violence policy.

- Findings highlight the importance of distinguishing between willingness to perpetrate violence and the opportunities for doing so.

- Both distinctions improve policymakers’ ability to identify the timing of attacks and tailor effective policy solutions.

- Generally, the study highlights the importance of accounting for socioeconomic and political contexts when devising policy solutions for climate-driven violence.

Overview

Researchers and policymakers often claim that harsh climatic conditions intensify the risk of civilian victimization by acting as a “threat multiplier.” Yet case-based evidence 1Benjamin E. Bagozzi, Ore Koren, and Bumba Mukherjee, “Droughts, Land Appropriation, and Rebel Violence in the Developing World,” Journal of Politics 79, no. 3 (2017): 1057–1072, https://doi.org/10.1086/691057; Tobias Ide, Anders Kristensen, and Henrikas Bartusevičius, “First Comes the River, Then Comes the Conflict? A Qualitative Comparative Analysis of Flood-related Political Unrest,” Journal of Peace Research 58, no. 1 (2021): 83–97, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343320966783. and new data2Justin Schon and Ore Koren, “Introducing AfroGrid, a Unified Framework for Environmental Conflict Research in Africa,” Scientific Data 9, no. 1 (2022): 116, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01198-5. suggest that locations with seasonal climate variations may face a higher risk of civilian targeting than locations with permanently harsh climatic conditions, e.g., because populations accustomed to climate stress are able to develop adaptation practices that protect their agricultural and food security.

Focusing on the Sahel and the Sahara Desert transition zone, this report develops a conditional policy framework to better understand the causes of and improve preparedness for climate-driven civilian targeting by armed actors. We focus on seasonal variations in agricultural resource productivity, a key part of oft-used definitions of environmental security,3Nina Græger, “Environmental Security?,” Journal of Peace Research 33, no. 1 (1996): 109–116. and claim that if climate stress can incentivize violence, these effects will be more likely in locations where environmental conditions are only sometimes, not always, harsh. We hence focus on areas prone to climate stress, areas where sudden improvement and decline in environmental health are a standard feature.

Practically, we link climate stress and environmental security by building on political violence research frameworks that conceptualize conflict onset based on both the willingness to engage in violence and the opportunity to do so. 4Karin Dyrstad and Solveig Hillesund, “Explaining Support for Political Violence: Grievance and Perceived Opportunity,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 64, no. 9 (2020): 1724–1753, https://doi-org/10.1177/0022002720909886; Randolph M. Siverson and Harvey Starr, The Diffusion of War: A Study of Opportunity and Willingness (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1991). This framework is useful because it captures not only where violence is most likely to occur, but also when violence is most likely to occur, adding variation and nuance to classic violence and conflict onset arguments. According to our expectations, the willingnessto target civilians will be higher where climate conditions are harsher, which creates competition over agricultural resources, food, and water. Willingness alone, however, is often insufficient in explaining conflict; unless there is an opportunity to engage in violence, individuals and groups are unlikely to do so. To approximate opportunity from an environmental-centric perspective, we incorporate environmental seasonality, which shapes local availability of agricultural resources.

We hypothesize that while climate-harsh locations are more likely to induce willingness on the part of the military, rebels, and militias to engage in violence along resource scarcity lines, they will only act on these incentives whenenvironmental conditions improve. In these times, more resources are available, facilitating military operations and allowing groups and military organizations — especially those living off locally-sourced food and other resources — to support their troops effectively.

Our research design and testing approach relies on a combination of evidence from a recently released fine-grained data framework for climate-conflict analysis5Schon and Koren, “Introducing AfroGrid.” combined with case studies of two conflict “hot zones” in the Sahel, where it has been proposed that environmental variations might feed into ongoing insurgency trends and, by extension, civilian victimization. These cases are (i) Burkina Faso and (ii) northeastern Nigeria.

Building on these findings, the last section of this report discusses specific triggers of civilian targeting, highlighting contexts and times where such risk factors are most likely to generate violence, and delineating new policy suggestions to mitigate these adverse impacts. Briefly, we illustrate the importance of separating the where from the when in emphasizing when opportunities for environmentally driven violence are highest, thereby showing that preventive and preemptive policy initiatives to address climate stress should focus not only on specific locations, but also time-relevant interventions to achieve maximal impact most effectively.

Concepts and Definitions

Environmental Security

For our purposes, environmental security is defined as the “health” of a given location as it pertains to aspects such as agricultural production, soil erosion, deforestation, air and water quality, etc.6Barry Buzan, Ole Wæver, and Jaap de Wilde, Security: A New Framework for Analysis, Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1998; Græger, “Environmental Security?” Definitions of environmental security often focus on the sustainable utilization of the environment, especially with respect to (agricultural) resource availability and access. Considering these issues, we theorize — and operationalize — environmental security as the degree of health of the local vegetation (empirically using the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index, as discussed below). As a result, we can capture local levels of agricultural sustainability in a comparable manner across all African locations, creating a framework for operationalizing direct impacts of environmental variations rather than using variables that only indirectly measure environmental variations as seen in much of the literature, i.e., rainfall, flooding, droughts, temperature, and soil health. Environmental (in)security is about the day-to-day- and local-level impacts of an area, while climate (in)security is about the overall and over-time conditions of an area.

Harsh Climate

Accordingly, we distinguish between environmental security and harsh climatic conditions. Climatic conditions are broader and more concerned with averages over time than environmental conditions. While the latter have some implications for environmental security, climatic conditions are nevertheless distinct phenomena. So, for instance, climate proxies with relevant implications (e.g., temperature, rainfall) have been heavily deployed in climate-conflict research; however, environmental security can exist even in areas where such proxies show extremely high/low values. An area could have a high level of vegetative health even during drought, for instance, because it is located downstream from a reservoir, or because the crops produced are drought resistant. At the same time, climate-harsh areas do make it, on average, harder to achieve environmental security all year long, a challenge that can shape the incentive structure of armed actors.

Sahara Desert Transition Zone

We theorize that climate and environmental conditions can involve different pathways and different direct impacts, while also recognizing the mutual relationship between the two. Our decision to focus on the Sahara Desert transition zone within the Sahel is directly motivated by our aim of examining the important intersection between climate and environmental conditions, an interaction that refers to how environmental security and natural resources abundance vary during the year within climate-harsh areas (both defined above). Sahara transition zones are a “most-likely case”7Jason Seawright and John Gerring, “Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research: A Menu of Qualitative and Quantitative Options,” Political Research Quarterly 61, no. 2 (2008): 294–308. where this interaction manifests. Such transition areas are defined by the year-round existence of climate-harsh conditions, but also exhibit marked variability with respect to environmental conditions and environmental security (as defined above). Importantly, researchers and policymakers have highlighted these issues when studying violence and conflict in the Sahara Desert transition zones, underscoring the role of climatic stress in these regards.8Neela Banerjee, “Climate Change Will Increase Risk of Violent Conflict, Researchers Warn,” Inside Climate News, June 13, 2019, https://insideclimatenews.org/news/13062019/climate-change-global-security-violent-conflict-risk-study-military-threat-multiplier/; A. Evans, Resource Scarcity, Climate Change and the Risk of Violent Conflict 2010, Washington, DC: World Bank. © World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/9191 License: CC BY 3.0 IGO, 24; Elisabeth A. Gilmore and Halvard Buhaug, “Climate Mitigation Policies and the Potential Pathways to Conflict: Outlining a Research Agenda,” WIREs Climate Change 12, no. 5 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.722; Malin Mobjörk, Florian Krampe, and Kheira Tarif, Pathways of Climate Insecurity: Guidance for Policymakers, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), 2020, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2020-11/pb_2011_pathways_2.pdf; Robert Muggah and José Luengo Cabrera, “The Sahel Is Engulfed by Violence. Climate Change, Food Insecurity and Extremists Are Largely to Blame,” World Economic Forum, 2019, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/01/all-the-warning-signs-are-showing-in-the-sahel-we-must-act-now/; Kirby Reiling and Cynthia Brady, Climate Change and Conflict: An Annex to the USAID Climate-Resilient Development Framework, United States Agency for International Development (USAID), February 2015, https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1866/ClimateChangeConflictAnnex_2015%2002%2025%2C%20Final%20with%20date%20for%20Web.pdf.

Civilian Targeting

Finally, our theoretical and empirical definitions of civilian targeting similarly build on past research that specifically focused on attacks against civilians.9Hanne Fjelde and Lisa Hultman, “Weakening the Enemy: A Disaggregated Study of Violence against Civilians in Africa,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 58, no. 7 (2014): 1230–1257, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002713492648; Ore Koren and Benjamin E. Bagozzi, “Living Off the Land: The Connection between Cropland, Food Security, and Violence against Civilians,” Journal of Peace Research 54, no. 3 (2017): 351–364, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343316684543. Here, we are also motivated by recent concerns raised by policymakers about potential linkages between climate, organized insurgency, and human security in the Sahel.10Evans, Resource Scarcity; Muggah and Cabrera, “The Sahel Is Engulfed by Violence”; United Nations (UN), “Conflict, COVID, Climate Crisis, Likely to Fuel Acute Food Insecurity in 23 ‘Hunger HHotspots,’ ” July 30, 2021, https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/07/1096812. Nevertheless, our policy framework is generalizable to other forms of conflict contexts, including fighting between different nonstate actors (e.g., farmer-herder) and attacks by militias. Empirically, we hence take a broad approach to civilian victimization, examining a range of incidents involving different actors, casualty rates, and types, which were obtained from several different sources.

An Interactive Policy Framework of Environmental Violence

Climate risk — defined broadly as a “condition under which the effects of climate variability and/or change are represented as threatening to a group of affected actors”11Michael Mason, “Climate Insecurity in (Post)Conflict Areas: The Biopolitics of United Nations Vulnerability Assessments,” Geopolitics 19, no. 4 (2014): 807, https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2014.903393. — presents a threat that may yield a variety of responses. Arguments centered on threat multipliers highlight the capability of climatic stress to aggravate existing grievances, and, correspondingly, the ability of societies to adapt to environmental conditions if they possess sufficient state capacity and tools for resilience. Climate stress — including extreme rainfall deviations (rains and droughts) and heatwaves — may aggravate existing grievances by exacerbating political and economic inequality, intensifying competition over agricultural resources, increasing strains on food and herding systems, and weakening the capacity of the state (which is crucial considering state responses to climatic stress play a critical role in influencing whether violence may arise as a result of widespread grievances against the state or other groups).

The threat multiplier argument suggests that remote locations subject to climate-harsh conditions are particularly likely to experience intensified grievances along existing fracture lines, and therefore more likely to experience civilian targeting. As mentioned above, such risk is especially likely in Sahara Desert transition zones within the Sahel considering these areas are generally subject to harsh climates. At the same time, constant climate harshness is insufficient — in and of itself — to explain when violence would intensify. Indeed, climatic shocks can produce positive peace outcomes in some contexts, since armed groups sometimes reduce operations during times of environmental insecurity, or might prefer to avoid climate-harsh areas, and increase their attacks when environmental conditions are improved.12 Note: Ide, Kristensen, and Bartusevičius, “First Comes the River, Then Comes the Conflict?”

This is where opportunity, namely the conditions that allow for armed groups to mobilize and create incentives for looting and appropriation, becomes important. Natural resource abundance, especially in remote areas within weak states, has been shown to be an important generator of opportunities because of such rapacity-based motivations.13Halvard Buhaug, Scott Gates, and Päivi Lujala, “Geography, Rebel Capability, and the Duration of Civil Conflict,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 53, no. 4 (2009): 544–569, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002709336457; Paul Collier and Anke Hoeffler, “Greed and Grievance in Civil War,” Oxford Economic Papers 56, no. 4 (2004): 563–595, https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpf064; Benjamin Crost and Joseph H. Felter, “Export Crops and Civil Conflict,” Journal of the European Economic Association 18, no. 3 (2020): 1484–1520, https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvz025; Macartan Humphreys, “Natural Resources, Conflict, and Conflict Resolution: Uncovering the Mechanisms,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 49, no. 4 (2005): 508–537, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002705277545; Ore Koren, “Food Abundance and Violent Conflict in Africa,” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 100, no. 4 (2018): 981–1006, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aax106; Reed M. Wood, “Rebel Capability and Strategic Violence against Civilians,” Journal of Peace Research 47, no. 5 (2010): 601–614, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343310376473. Climate-harsh areas will experience, on average, lower levels of environmental security. Fewer food crop types may be grown in climate-harsh areas, particularly when breakdowns in markets and supply chains are taken into account.14Tracy Kuo Lin et al., “Food Insecurity in the Context of Conflict: Analysis of Survey Data in the Occupied Palestinian Territory,” Lancet 398, suppl. 1 (2021): S35, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01521-X. With less crop diversification and income stability, regions may lose adaptive capacity and — by extension — environmental security. Facing acute environmental insecurity and a lack of state response, households may view participation in violence as a short-term way to address these adverse impacts.

At the same time, because environmental insecurity does not equal climate insecurity, environmental insecurity is not constant within climate-harsh areas, where agricultural resource abundance varies over time. In this case, environmental security can increase agricultural resource productivity (i.e., cash crops, food, water). For instance, some areas of the Sahel (e.g., northeastern Nigeria) are generally very arid, and rainfall averages well below 200 mm per year. When it does rain, it tends to happen in specific months, often leading to floods. For farmers that depend on rain-fed agriculture, this means the most productive months are when rainfall happens and when temperatures are moderate — not too hot, not too cold — which prevents immediate evapotranspiration and facilitates growth and productivity. Moreover, reservoirs in some areas mean that farmers can improve their productivity even when periods of ideal temperature do not coincide with times of ideal rainfall. All these features mean that climate-arid areas still experience variability in environmental security and agricultural productivity during different parts of the year.

In line with the rapacity-centric logic discussed above, civilian targeting rates in these climate-harsh areas will be dependent on environment and agricultural opportunities to engage in appropriation.15 Koren and Bagozzi, “Living Off the Land.” One reason is that during these times, organizations and groups have greater opportunity to recruit and mobilize troops by selling resources they appropriate, directly consuming them, or both. A second reason is that targeting civilians in areas with greater agricultural resource abundance helps to weaken the rivals by preventing them from gaining access to these resources. Third, where populations developed adaptation methods to survive, seasonal environmental insecurity can increase opportunistic incentives to engage in violence when environmental security is greater, to increase resilience to future times of insecurity.

Accordingly, we argue that civilian targeting is unlikely to result from climatic conditions unless there is both willingness and opportunity to engage in it. We propose a conditional climate-centric policy framework of preventing civilian targeting where mitigation efforts should focus on (i) harsh climate areas (where grievances are prevalent) when (ii) there is greater opportunity to engage in violence.

Geospatial Evidence

Our geospatial evidence section utilizes a new disaggregated data framework, AfroGrid, specifically designed to study climate-conflict relationships in Africa. AfroGrid measures geospatial information on conflict, development, and environmental conditions at the local geographic “cell” (55 km × 55 km at the equator, or 0.5 decimal degree) monthly level.16 Note: Schon and Koren, “Introducing AfroGrid.” We are most interested in climate-harsh areas, particularly Sahara Desert transition zones, where we hypothesize climate risk–driven grievances are most likely. To identify these Sahara Desert transition zones, we incorporate monthly variation in the Sahara Desert’s vegetation boundary. This shifting boundary directly relates to the intersection between climate harshness and environmental security. Transition zones include areas with little preexisting risk of violence, such as western Mali and southern Mauritania, as well as areas with a high preexisting risk of violence, such as the border region between Mali–Burkina Faso–Niger, Lake Chad’s surrounding area of Niger–Nigeria–Cameroon, and Darfur, Sudan, among other areas.

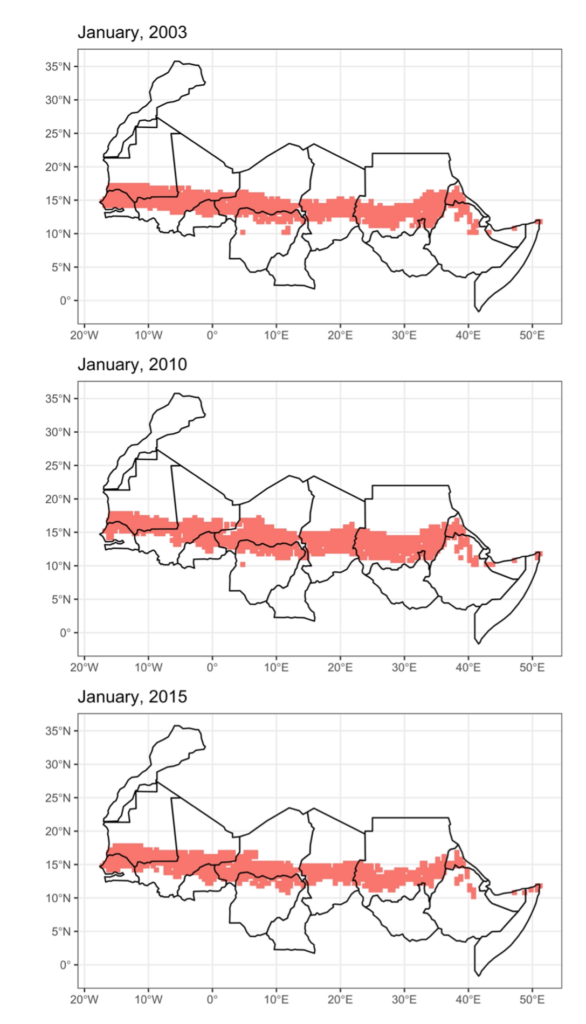

To identify shifting vegetation boundaries, we calculate the predicted vegetation coverage value (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index, or NDVI) when precipitation is at 200 mm or more (the typical climatic standard to measure deserts). Incorporating AfroGrid’s monthly level advantage, we then count the number of months in the year when each grid cell has a level of vegetation health that falls below our predicted threshold when precipitation is at 200 mm. If a geographic cell’s level of vegetation coverage fails to reach our predicted environmental security threshold for 1–11 months during a given year, we define it as a desert transition zone. Locations that are environmentally insecure according to this metric always face desert-like conditions (i.e., all 12 months of the year); locations that are never environmentally insecure based on this metric never experience desert-like conditions (i.e., 0 months of the year). A desert transition zone, by contrast, is temporarily environmentally insecure during parts of the year, and experiences some level of relative security in others. Because we are interested in the expansion of the Sahara Desert, we retain these values only for African grid cells whose latitude is between 10 degrees and 20 degrees North. For illustration, Figure 1 plots locations that fall under the Desert transition zone definition for several randomly selected years — 2003, 2010 (which appears to be drier than the other two), and 2015.

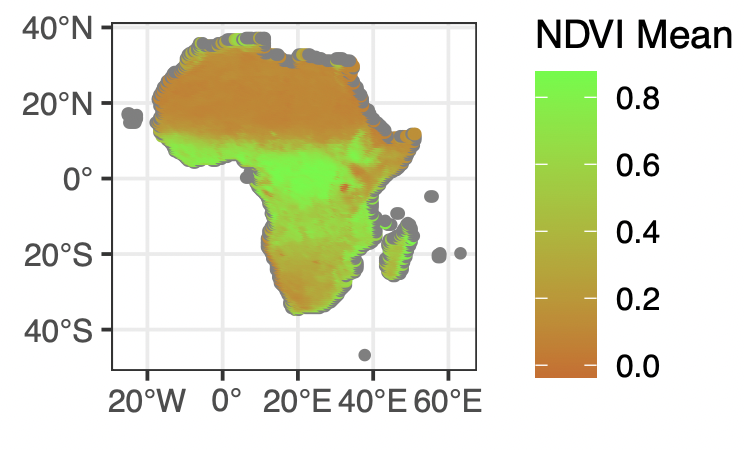

To approximate the opportunity aspect of our policy framework, namely variability in environmental security and resource abundance, we directly incorporate monthly levels of vegetation health (ranging from 0, or no vegetation, to 1, or full vegetation coverage), lagging them by one month to account for the time such effects might take to translate into civilian targeting. For illustration, Figure 2 records vegetation health (at the local level) for one randomly selected month (June 2011) across the entire African continent. Below, we examine the conditional relationship underlying our policy framework, discussing the methods and models we used to compile these plots in Appendix I.

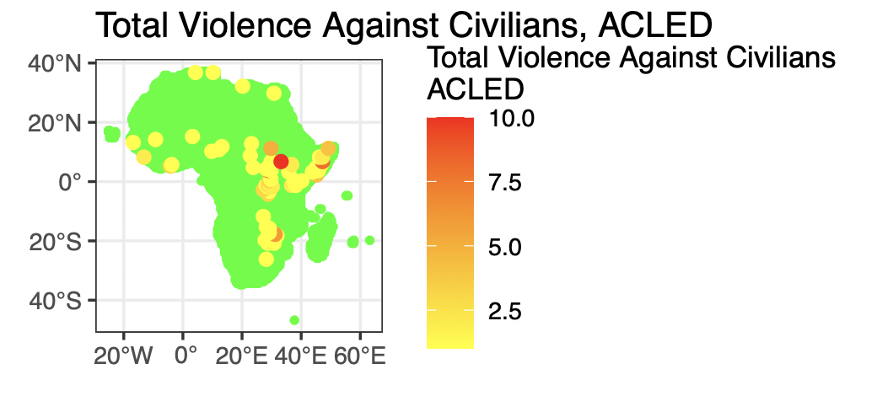

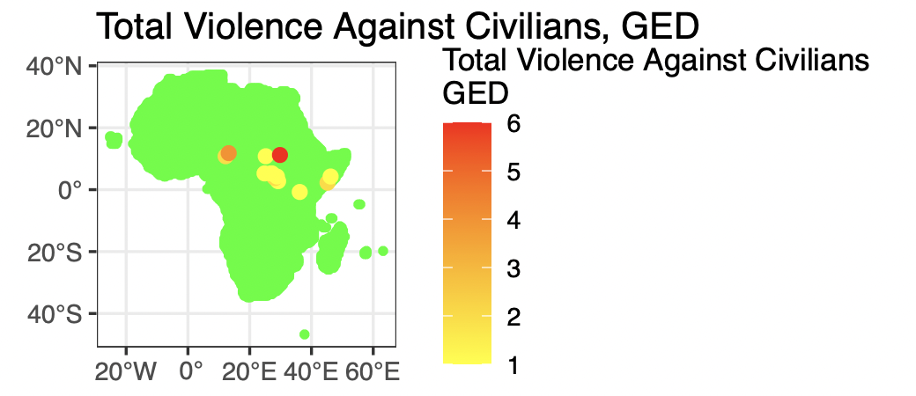

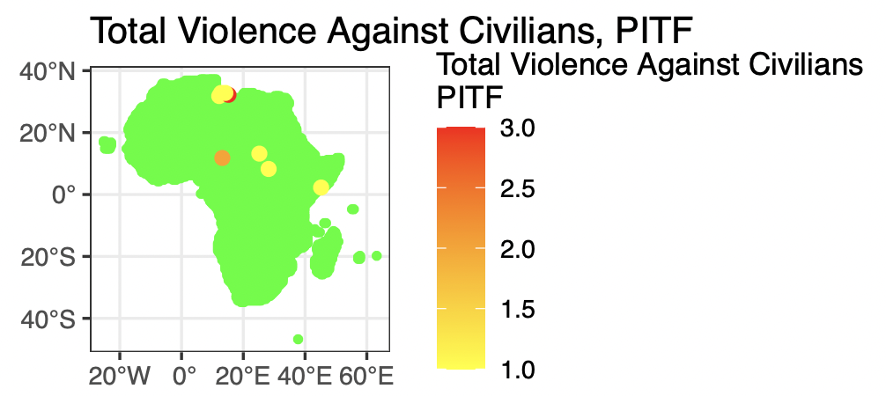

AfroGrid also includes information on civilian targeting by different actors from three key datasets: (i) Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset (ACLED), which uses a minimal threshold (any attacks against civilians, even those without casualties); (ii) Geolocated Event Dataset (GED), which uses a slightly more constricted threshold (attacks where at least one civilian was intentionally killed taking place as part of a civil war with at least 25 deaths); and the Political Instability Task Force’s Worldwide Atrocity Dataset (PITF) (which measures incidents where at least five civilians were intentionally killed).17Raleigh et al., “Introducing ACLED: An Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset: Special Data Feature.” Journal of Peace Research 47, no. 5 (2010): 651-660. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343310378914; Sundberg and Melander. “Introducing the UCDP Georeferenced Event Dataset.” Journal of Peace Research 50, no. 4 (2013): 523-532. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343313484347. All these datasets include verified incidents and are the most widely used conflict datasets. However, to make sure that we are not making incorrect inferences, we have separately (i) focused only on cases that were coded as undisputed reports; and (ii) focused only on cases that could be accurately identified to the to the district or village level and (iii) measured at the monthly, weekly, or daily level. For illustration, Figure 3 plots civilian targeting incidents (aggregated for all actors) recorded by these three datasets during the same randomly selected month of June 2011.

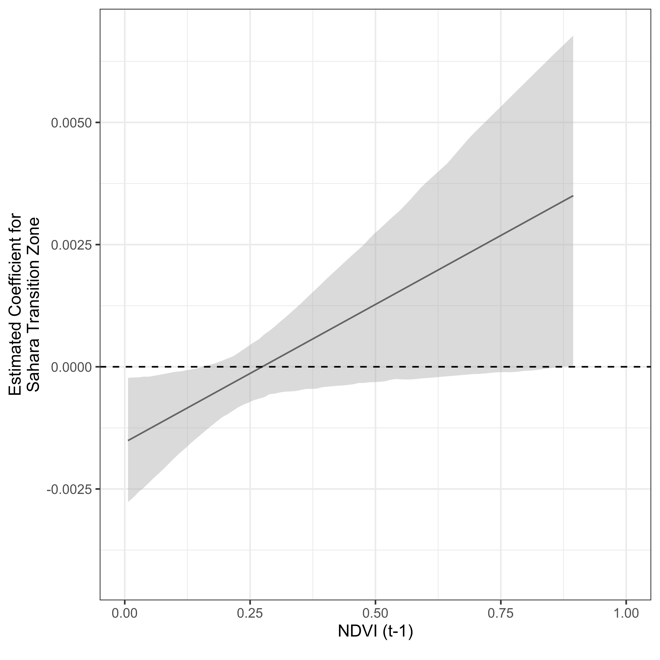

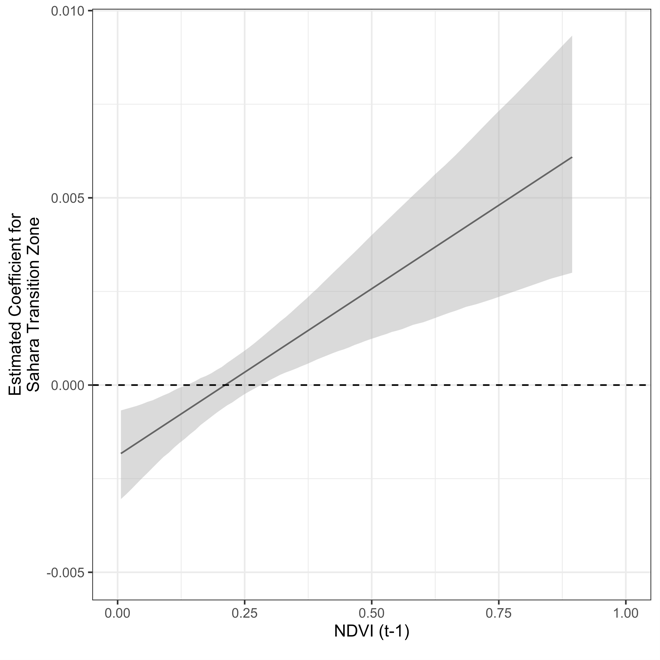

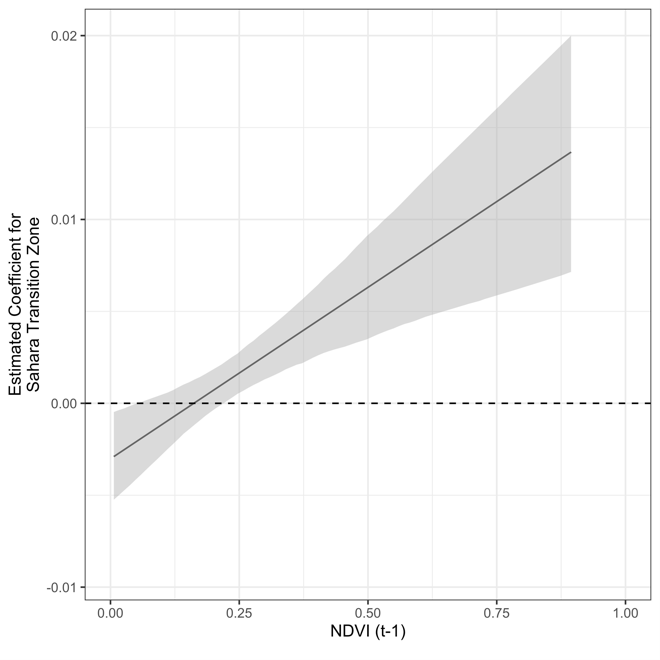

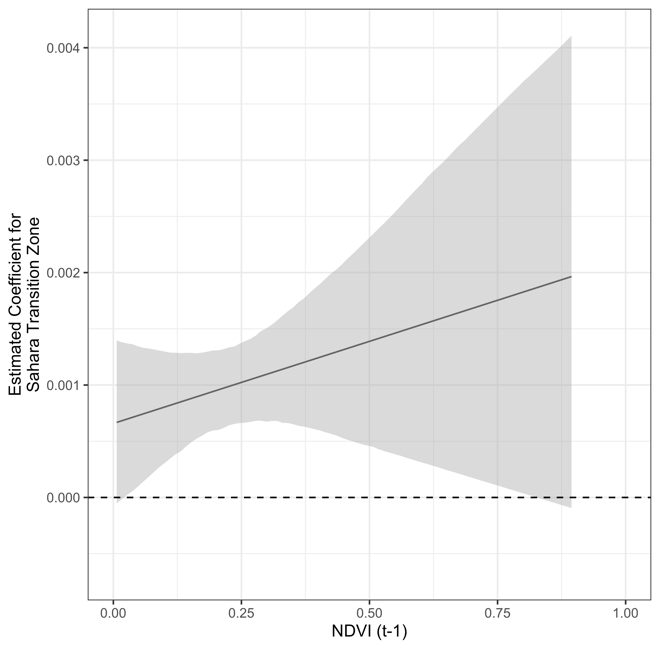

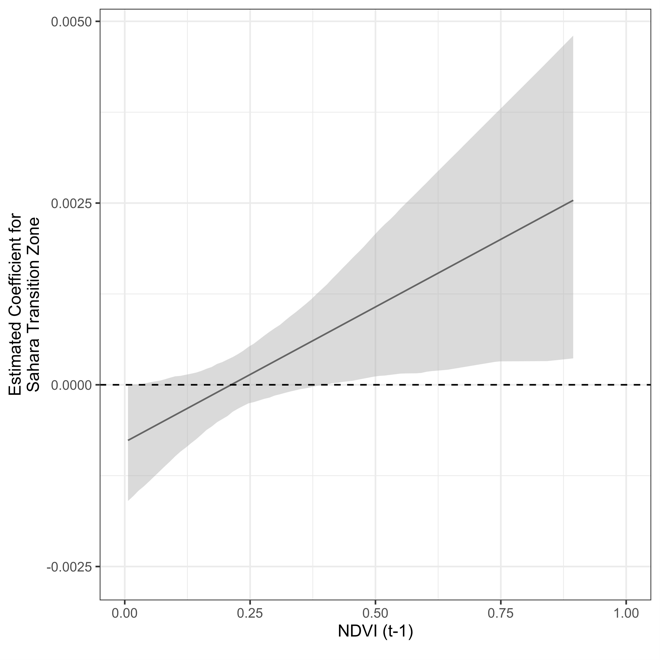

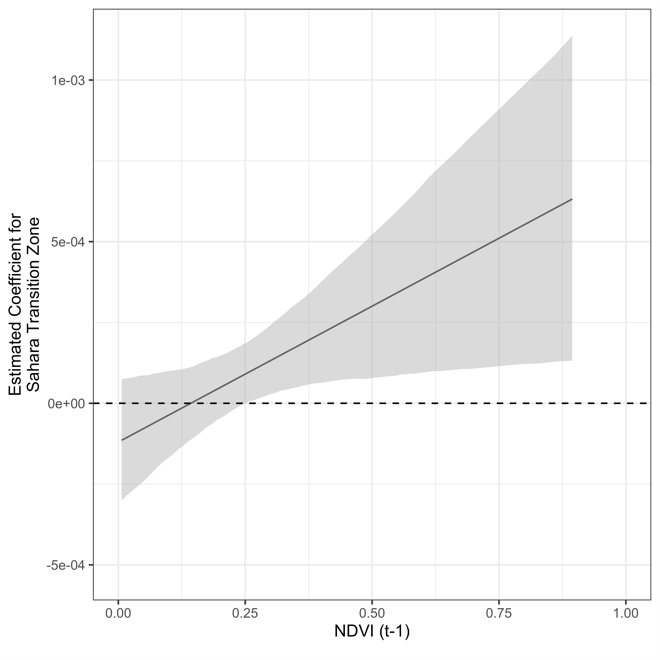

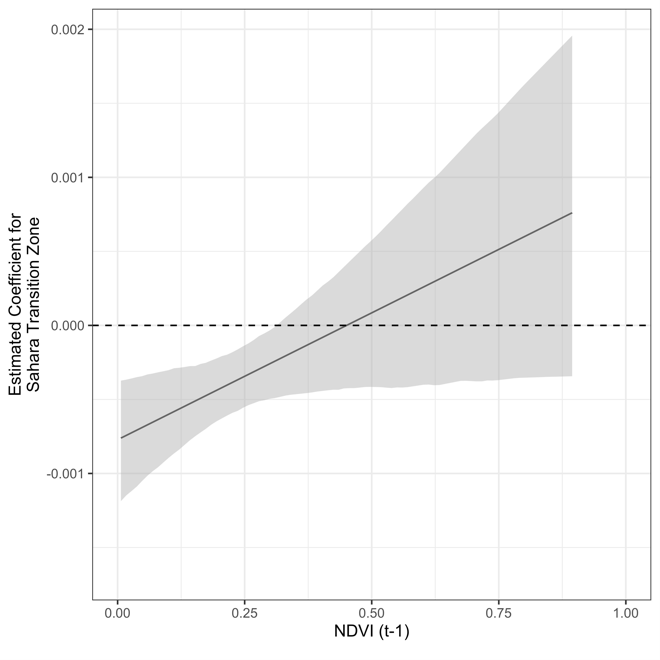

A more systematic evaluation of the conditional relationship between climate harshness in the Sahara Desert transition zone and changing environmental security and resource abundance levels — evaluated for each location and each month between January 2003 and December 2018 — is provided in Figure 4. Each plot in this figure shows how the expected number of civilian targeting incidents within Sahara transition zones (y axis) changes as environmental security increases from 0 (no vegetation) to 1 (full vegetation), compared with the average rate of attacks across the rest of the continent, i.e., in non-Sahara transition zones (the gray bands are where 95% of the simulations fall). The methods and models used to compile these figures are discussed in Appendix I.

As shown, in every case — with the possible exception of attacks initiated by state forces as measured by the GED — Sahara transition zones (climate-harsh areas) experience a negative rate of civilian targeting incidents by both state and nonstate actors when there is no agricultural productivity compared with the rest of the continent. However, as environmental security (vegetation health) levels improve, the expected number of attacks on civilians in these cases rises and quickly passes the continental average. The results therefore confirm our general claims about the conditionality of the climate–environment–civilian targeting relationship broadly. Yet, to ensure the relationship we identify makes sense and to provide for a more contextual evaluation of this relationship, we provide specific evidence of the relevant mechanisms from two cases in the next section.

Figure 4: Change in Frequency of Civilian Targeting in Sahara Desert Transition Zones.

Case-Based Evidence

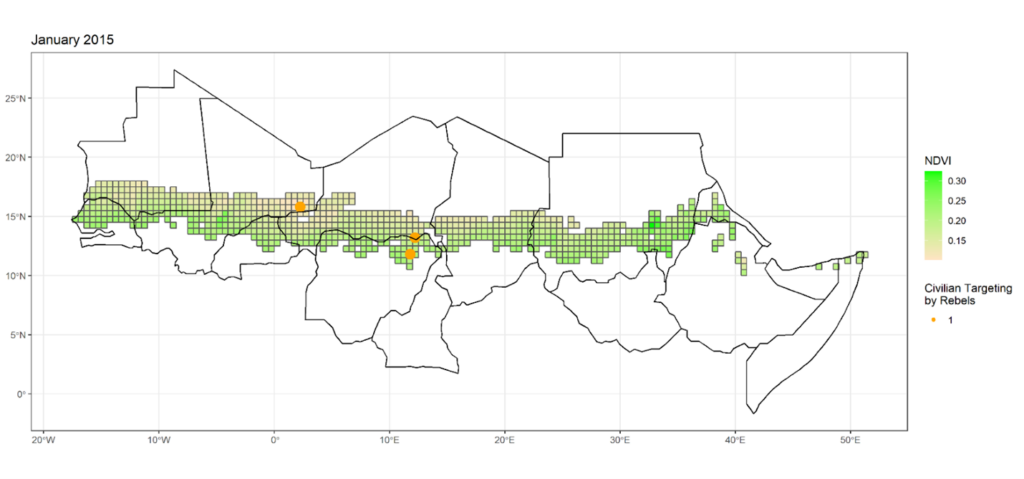

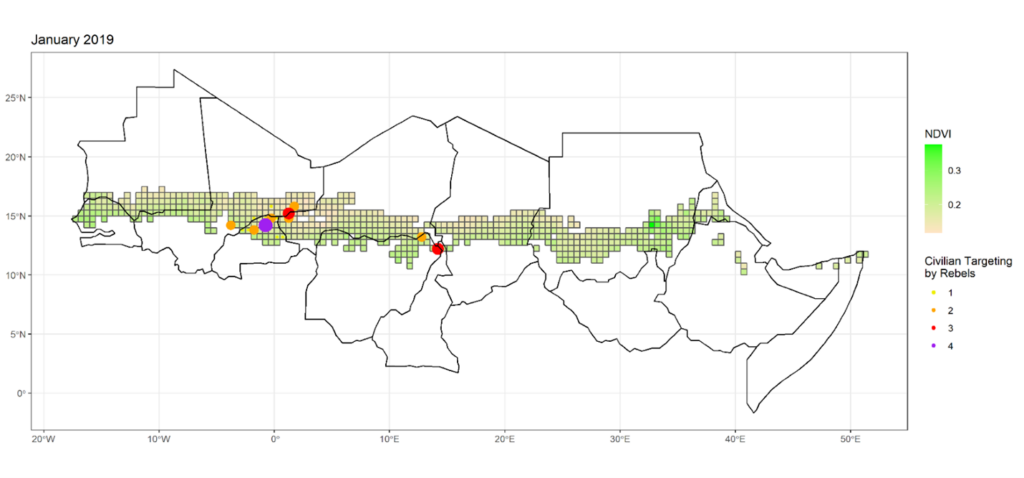

Below we discuss two cases of regions within the Sahara transition zone, highlighting the role of variability in environmental security and resource and food crop abundance therein. Both Burkina Faso and Nigeria have been embroiled in conflict over the last two decades, and the United Nations and international organizations have highlighted both countries as being at a high risk of climate deterioration and insecurity. Importantly for our purposes, both Burkina Faso and northeastern Nigeria are located in the Sahel and include part of the Sahara transition zones. This means that in both regions, climate-harsh areas experience some months of greater environmental security. These different features make these countries effective “most likely”18 Note: Seawright and Gerring, “Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research.” test cases to examine whether violence by different actors varies based on the mechanisms we propose. For illustration, Figure 5 plots civilian targeting events by rebels in Sahara transition zones in both regions for two randomly selected months during which violence was recorded in each region (January 2015 and January 2019), as well as vegetation health in each of these transition locations.

Burkina Faso

Climate insecurity brokers the willingness of terrorist groups and government security forces to target civilians in an area where violence occurs regularly. But it is when there is an increase in food production (e.g., during harvest) that the opportunity arises for civilian targeting to be the most effective. In Burkina Faso, climate variability and its potential impact on planting and harvesting seasons is an increasing concern. At the same time, Terrorist groups and state security forces have been in conflict for over a decade. The situation has deteriorated since an Islamist insurgency arose in the aftermath of a 2014 uprising that overthrew the then-President Blaise Compaoré. The uprising included a dismantling of the security services, which created a vacuum that Islamists rushed to fill. Neither rebels nor the state has prioritized the protection of civilians.

With the risk of fewer crops being harvested but more people needing them every year, times of food abundance create an opportunity for rebels and the state to use violence to appropriate the limited food that exists. The length of the growing season may have also been variant as a result of desertification and harsh droughts. This variation may have caused some to turn to other means of survival — mainly tree cutting (which has only worsened desertification) and gold mining (which has caused massive migrations to gold mining areas that are unable to support large groups of people) — that have had negative long-term effects on the land.19United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Climate Risks in Food for Peace Geographies: Burkina Faso, 2017, https://www.climatelinks.org/sites/default/files/asset/document/20170807_USAID%20ATLAS_FFP_BurkinaFaso.pdf.

Since 2019, rates of violence against civilians have increased dramatically, but not consistently or simultaneously. This may have correlated with food- and other agriculturally related pressures. Rebel groups, such as the Jihadist groups that originated in Mali and Niger as well as homegrown groups from the north,20 Note: Anna Schmauder, Customary Characters in Uncustomary Circumstances: The Case of Burkina Faso’s Est Region, United States Agency for International Development (USAID), 2021, https://customarylegitimacy.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/2022-02/customary_legitimacy_Est_0.pdf. have increased the frequency with which they are stealing crops and livestock and more aggressively chasing farmers off their land, primarily during harvest months.21Sam Mednick, “Hunger Grips Burkina Faso due to Increasing Jihadi Violence,” Washington Post, April 26, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/hunger-grips-burkina-faso-due-to-increasing-jihadi-violence/2022/04/26/256f5508-c541-11ec-8cff-33b059f4c1b7_story.html. This caused rapid decreases in food supply and worsened the hunger crisis throughout the country. This impact was compounded by severe flooding during the rainy season, whose impact may be exacerbated by deforestation and soil erosion, which limited the ability of farmers to plant and harvest crops.22 Medecins Sans Frontières, Burkina Faso: Living Conditions Worsen for Displaced People as Violence Escalates and Rainy Season Begins, July 20, 2020, https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/latest/burkina-faso-living-conditions-worsen-displaced-people-violence-escalates-and-rainy-season. There are concerns that this increases the rates of clashes between herders and farmers, as the former must travel further in search of new grazing areas, often crossing farmlands. These stresses have been exacerbated by a collapse in state security services, generally, by several coups in recent years (including the most recent one on 23 January 2022) as well as by the thousands of Burkinabe who have been fleeing recent fighting while receiving little support from the government.

In line with our framework, the apparent harshness of local climatic conditions, including frequent droughts, floods, higher desertification risks, and soil erosion, may explain why rebels, militias, and the government forces alike are willing to use violence. However, with security forces being generally ineffective at protecting civilians, times where resources are available in relative abundance (e.g., after harvest) attract higher rates of civilian targeting, as these different actors seek to appropriate resources for consumption, trade, and preemption.

Northeastern Nigeria

Despite some efforts to fight climatic impacts, northeastern Nigeria suffers from heat waves, extreme rainfall deviations, and increased flooding and droughts, which may intensify if climate change trends hold true.23United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Climate Risk Profile: Nigeria. 2019, https://www.climatelinks.org/sites/default/files/asset/document/2019_USAID-ATLAS-Nigeria-Climate-Risk-Profile.pdf. These issues have led to displacement and internal migrations from rural to urban areas. Bettwen1960 and 1990, Lake Chad shrank by nearly 90% (potentially due a combination of damming and droughts). Since the 1990s, water levels in Lake Chad have been stable, but this stability has not been able to effectively support agricultural livelihoods in northeastern Nigeria.24Binh Pham-Duc et al., “The Lake Chad Hydrology under Current Climate Change,” Scientific Reports 10, no. 1 (2020): 5498, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62417-w.

Herders, mostly Fulani, have had to minimize their areas of roaming, and farmers who were able to use irrigation techniques to live farther away from Lake Chad have had to move closer to the lake. Herders have also had to move south into forest areas to feed their livestock, which increases their rates of interaction with farmers and may contribute to deforestation.25Olalekan Waheed Adigun, “A Critical Analysis of the Relationship Between Climate Change, Land Disputes, and the Patterns of Farmers/Herdsmen’s Conflicts in Nigeria,” Canadian Social Science 15, no. 3 (2019): 76–89. Both famers and herders have been pressured — sometimes by the state — to maintain crop and herd productivity levels, but they receive little to no government help.26Adigun, “A Critical Analysis.”

Another rising threat to civilians comes from Boko Haram. The group’s initial tactics involved destroying multiple crops of food, killing cattle, and forcing farmers to flee their homes and farmland.27 Note: Henry Kam Kah, “ ‘Boko Haram Is Losing, But So Is Food Production’: Conflict and Food Insecurity in Nigeria and Cameroon,” Africa Development 42, no. 3 (2017): 177–196. They also targeted specific farms and farmers who were not supportive of their cause or forced farmers to pay taxes in order to access their own farms. Those farmers that refuse to or cannot pay the taxes are then forced off their farms, and sometimes those farms are destroyed. This has led to massive market closures and is worsening the food crisis in the whole region.28 Note: Kah, “Boko Haram Is Losing.” The farmers that are forced to flee often move to urban or they move to neighboring farming communities that are suffering from similar circumstances, straining resources even further.

As resources have diminished as a result of conflict and potentially intensified climate harshness, Boko Haram switched to targeting civilians directly (mainly the farmers and herders themselves) during times of relative abundance, when crops and cattle are available to support their troops. Indeed, in line with our framework, worsening climate and socioeconomic conditions pushed the group to use violence more strategically to appropriate resources as they become available in greater quantities rather than simply destroying them to alter the civilians’ perception of the group or the government.

Policy Implications

The framework developed above, and the empirical evidence discussed in its support, suggest several relevant policy implications for improving the safety and security of civilians in areas subject to harsh climatic conditions.

Distinguishing climate from environmental security: Our framework relies on — and shows the importance of — separating the focus on harsh climate and climate change from the role of environmental security in general. While the two are related, they are not the same thing. First, policy solutions could be relatively effective in improving environmental security (e.g., by planting drought-resistant crops, improving coping mechanisms, building more effective houses, using fertilizer, building reservoirs) even if they fail to address climate change. Second, distinguishing between the two types of security allows policymakers to more specifically target the underlying motivations related to each with specific policies that can mitigate their impacts, rather than deploying one-size-fits-all solutions to prevent civilian targeting. Finally, this disaggregation allows policymakers to potentially achieve more effective outcomes (e.g., deploying protective deployments to specifically secure civilian farmers around the harvest or during other times when granaries and storage are full).

Addressing willingness-based motivations separately from opportunity-based ones: A second implication of our framework is in showing that climate-induced grievances are insufficient — in and of themselves — in generating higher rates of civilian targeting. While such grievances are important, as they provide groups with the willingness to use violence, we showed that without the opportunity for violence — provided by greater availability of agricultural resources — they are associated, at worst, with rates of targeting that are similar to the continental baseline. This suggests that civilian protection policies would be most effective if they focus on opportunities that could lead to targeting, e.g., by protecting areas where more food, cash crops, or cattle are grown, rather than trying to address the underlying grievances. While policies that target the latter are beneficial, these will most likely necessitate far more significant changes of socioeconomic contexts over much longer terms. Addressing opportunities, in contrast, can be done in a more directed way, although we also recognize that such approaches provide only short-term solutions.

Focusing on the potential timing of such attacks: Another implication of our framework is in showing the importance of timing. Climate-harsh areas might be indicative of where civilian targeting might arise — and where the rates of such attacks may increase in the future — but not when such attacks are most likely. Making a clear distinction between climate harshness and variations in environmental security allows us to provide an important perspective on the role of timing in climate-driven civilian targeting. This, in turn, can be used to optimize policy solutions so they can be effectively deployed more closely to periods of high risk, thereby both increasing the probability these policies will be effective and constraining resources by placing limits on the times when defense forces should be deployed to relevant locations.

Highlighting the importance of context: More generally, our framework illustrates the importance of accounting for the context when violence is taking place. This is especially important when climate change is concerned, considering the “one effect to rule them all” phenomenon that pervades climate-conflict research,29 Note: Halvard Buhaug, Lars-Erik Cederman, and Kristian Skrede Gleditsch, “Square Pegs in Round Holes: Inequalities, Grievances, and Civil War,” International Studies Quarterly 58, no. 2 (2014): 418–431, https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12068. which can have grave implications for our ability to actually prevent violence in these regards.30 Note: Courtland Adams, Tobias Ide, Jon Barnett, and Adrien Detges, “Sampling Bias in Climate–Conflict Research,” Nature Climate Change 8, no. 3 (2018): 200–203, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0068-2. The strongest predictors of violence are rarely climate-related; they tend to be a history of violence, whether there is an ongoing conflict, and the strength of the socioeconomic and political environments. To be sure, climate change is a major emerging challenge, with vast implications for all societies globally, including conflict. But its impacts — their direction (adverse or positive) and their severity — are ultimately a factor of the ability of different societies to address limitations, opportunities, and grievances peacefully. This also means that social environments that allow for — or at least do not prevent — violence as a political means will be more susceptible to its impacts than those that do not.

References

- Adams, Courtland, Tobias Ide, Jon Barnett, and Adrien Detges. “Sampling Bias in Climate–Conflict Research.” Nature Climate Change 8, no. 3 (2018): 200–203. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0068-2.

- Adigun, Olalekan Waheed. “A Critical Analysis of the Relationship Between Climate Change, Land Disputes, and the Patterns of Farmers/Herdsmen’s Conflicts in Nigeria.” Canadian Social Science 15, no. 3 (2019): 76–89.

- Angrist, Joshua D., and Jörn-Steffen Pischke. Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009.

- Bagozzi, Benjamin E., Ore Koren, and Bumba Mukherjee. “Droughts, Land Appropriation, and Rebel Violence in the Developing World.” Journal of Politics 79, no. 3 (2017): 1057–1072. https://doi.org/10.1086/691057.

- Banerjee, Neela. “Climate Change Will Increase Risk of Violent Conflict, Researchers Warn.” Inside Climate News, June 13, 2019. https://insideclimatenews.org/news/13062019/climate-change-global-security-violent-conflict-risk-study-military-threat-multiplier/.

- Beck, Nathaniel. “Estimating Grouped Data Models with a Binary-Dependent Variable and Fixed Effects via a Logit versus a Linear Probability Model: The Impact of Dropped Units.” Political Analysis 28, no. 1 (2020): 139–145. https://doi:10.1017/pan.2019.20.

- Buhaug, Halvard, Lars-Erik Cederman, and Kristian Skrede Gleditsch. “Square Pegs in Round Holes: Inequalities, Grievances, and Civil War.” International Studies Quarterly 58, no. 2 (2014): 418–431. https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12068.

- Buhaug, Halvard, Scott Gates, and Päivi Lujala. “Geography, Rebel Capability, and the Duration of Civil Conflict.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 53, no. 4 (2009): 544–569. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002709336457.

- Buzan, Barry, Ole Wæver, and Jaap de Wilde. Security: A New Framework for Analysis. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1998.

- Collier, Paul, and Anke Hoeffler. “Greed and Grievance in Civil War.” Oxford Economic Papers 56, no. 4 (2004): 563–595. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpf064.

- Crost, Benjamin, and Joseph H. Felter. “Export Crops and Civil Conflict.” Journal of the European Economic Association 18, no. 3 (2020): 1484–1520. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvz025.

- Dyrstad, Karin, and Solveig Hillesund. “Explaining Support for Political Violence: Grievance and Perceived Opportunity.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 64, no. 9 (2020): 1724–1753. https://doi-org/10.1177/0022002720909886.

- Evans, A. (2010). Resource Scarcity, Climate Change and the Risk of Violent Conflict. Washington, DC: World Bank. © World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/9191 License: CC BY 3.0 IGO.(p. 24).

- Fjelde, Hanne, and Lisa Hultman. “Weakening the Enemy: A Disaggregated Study of Violence against Civilians in Africa.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 58, no. 7 (2014): 1230–1257. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002713492648.

- Gilmore, Elisabeth A., and Halvard Buhaug. “Climate Mitigation Policies and the Potential Pathways to Conflict: Outlining a Research Agenda.” WIREs Climate Change 12, no. 5 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.722.

- Græger, Nina. “Environmental Security?” Journal of Peace Research 33, no. 1 (1996): 109–116.

- Humphreys, Macartan. “Natural Resources, Conflict, and Conflict Resolution: Uncovering the Mechanisms.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 49, no. 4 (2005): 508–537. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002705277545.

- Ide, Tobias, Anders Kristensen, and Henrikas Bartusevičius. “First Comes the River, Then Comes the Conflict? A Qualitative Comparative Analysis of Flood-related Political Unrest.” Journal of Peace Research 58, no. 1 (2021): 83–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343320966783.

- Kah, Henry Kam.“ ‘Boko Haram Is Losing, But So Is Food Production’: Conflict and Food Insecurity in Nigeria and Cameroon.” Africa Development 42, no. 3 (2017): 177–196.

- Koren, Ore. “Food Abundance and Violent Conflict in Africa.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 100, no. 4 (2018): 981–1006. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aax106.

- Koren, Ore, and Benjamin E. Bagozzi. “Living Off the Land: The Connection between Cropland, Food Security, and Violence against Civilians.” Journal of Peace Research 54, no. 3 (2017): 351–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343316684543.

- Lin, Tracy Kuo, Rawan Kafri, Weeam Hammoudeh, Suzan Mitwalli, Zeina Jamaluddine, Hala Ghattas, Rita Giacaman, and Tiziana Leone. “Food Insecurity in the Context of Conflict: Analysis of Survey Data in the Occupied Palestinian Territory.” Lancet 398, suppl. 1 (2021): S35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01521-X.

- Mason, Michael. “Climate Insecurity in (Post)Conflict Areas: The Biopolitics of United Nations Vulnerability Assessments.” Geopolitics 19, no. 4 (2014): 806–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2014.903393.

- Medecins Sans Frontieres. “Burkina Faso: Living Conditions Worsen for Displaced People as Violence Escalates and Rainy Season Begins.” July 20, 2020. https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/latest/burkina-faso-living-conditions-worsen-displaced-people-violence-escalates-and-rainy-season.

- Mednick, Sam. “Hunger Grips Burkina Faso due to Increasing Jihadi Violence.” Washington Post, April 26, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/hunger-grips-burkina-faso-due-to-increasing-jihadi-violence/2022/04/26/256f5508-c541-11ec-8cff-33b059f4c1b7_story.html.

- Mobjörk, Malin, Florian Krampe, and Kheira Tarif. Pathways of Climate Insecurity: Guidance for Policymakers. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), 2020. https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2020-11/pb_2011_pathways_2.pdf.

- Muggah, Robert, and José Luengo Cabrera. “The Sahel Is Engulfed by Violence. Climate Change, Food Insecurity and Extremists Are Largely to Blame.” World Economic Forum, 2019. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/01/all-the-warning-signs-are-showing-in-the-sahel-we-must-act-now/.

- Pham-Duc, Binh, Florence Sylvestre, Fabrice Papa, Frédéric Frappart, Camille Bouchez, and Jean-François Crétaux. “The Lake Chad Hydrology under Current Climate Change.” Scientific Reports 10, no. 1 (2020): 5498. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62417-w.

- Raleigh, Clionadh, Andrew Linke, Håvard Hegre, and Joakim Karlsen. “Introducing ACLED: An Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset: Special Data Feature.” Journal of Peace Research 47, no. 5 (2010): 651–660. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343310378914.

- Reiling, Kirby, and Cynthia Brady. Climate Change and Conflict: An Annex to the USAID Climate-Resilient Development Framework. United States Agency for International Development (USAID), February 2015. https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1866/ClimateChangeConflictAnnex_2015%2002%2025%2C%20Final%20with%20date%20for%20Web.pdf.

- Schmauder, Anna. Customary Characters in Uncustomary Circumstances: The Case of Burkina Faso’s Est Region. United States Agency for International Development (USAID), 2021. https://customarylegitimacy.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/2022-02/customary_legitimacy_Est_0.pdf.

- Schon, Justin, and Ore Koren. “Introducing AfroGrid, a Unified Framework for Environmental Conflict Research in Africa.” Scientific Data 9, no. 1 (2022): 116. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01198-5.

- Seawright, Jason, and John Gerring. “Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research: A Menu of Qualitative and Quantitative Options.” Political Research Quarterly 61, no. 2 (2008): 294–308.

- Siverson, Randolph M., and Harvey Starr. The Diffusion of War: A Study of Opportunity and Willingness. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1991.

- Sundberg, Ralph, and Erik Melander. “Introducing the UCDP Georeferenced Event Dataset.” Journal of Peace Research 50, no. 4 (2013): 523–532. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343313484347.

- United Nations (UN). “Conflict, COVID, Climate Crisis, Likely to Fuel Acute Food Insecurity in 23 ‘Hunger HHotspots.’ ” July 30, 2021. https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/07/1096812.

- United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Climate Risk Profile: Nigeria. 2019. https://www.climatelinks.org/sites/default/files/asset/document/2019_USAID-ATLAS-Nigeria-Climate-Risk-Profile.pdf.

- United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Climate Risks in Food for Peace Geographies: Burkina Faso. 2017. https://www.climatelinks.org/sites/default/files/asset/document/20170807_USAID%20ATLAS_FFP_BurkinaFaso.pdf

- Wood, Reed M. “Rebel Capability and Strategic Violence against Civilians.” Journal of Peace Research 47, no. 5 (2010): 601–614. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343310376473.

Appendix I: Methods and Models

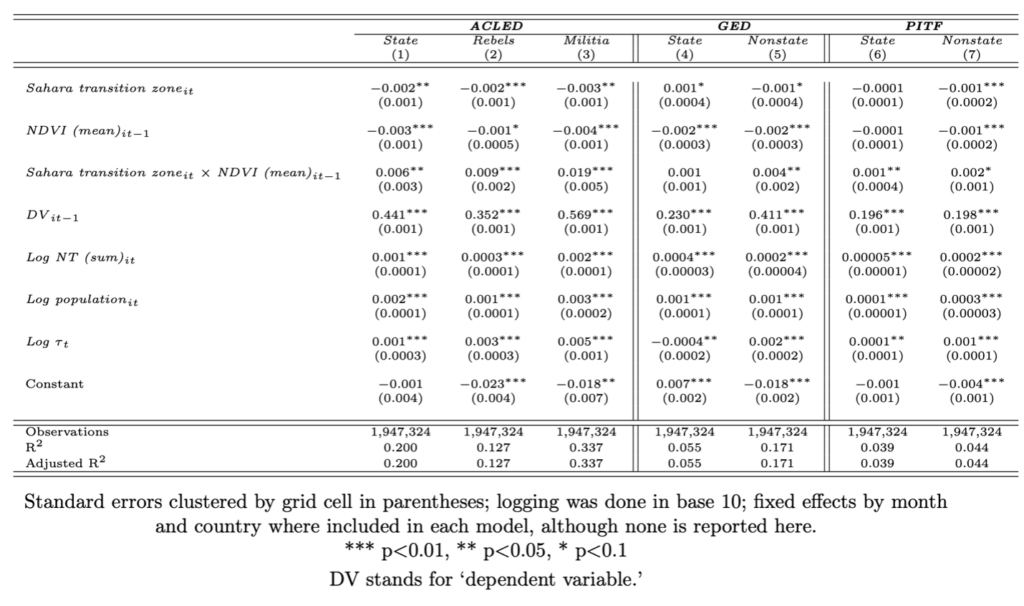

Our different indicators of violence against civilians can be treated as continuous, allowing us to rely on ordinary least squares (OLS) estimation.31 Note: Most econometric research (e.g., Joshua D. Angrist and Jörn-Steffen Pischke, Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion [Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009]) and political methods research (e.g., Nathaniel Beck, “Estimating Grouped Data Models with a Binary-Dependent Variable and Fixed Effects via a Logit versus a Linear Probability Model: The Impact of Dropped Units,” Political Analysis 28, no. 1 (2020): 139–145, https://doi:10.1017/pan.2019.20) argue in favor of using OLS within two-way fixed effects settings. Count models, under these conditions, could create inferential bias by omitting zero-only observations. Our models are specified as follows:

Here, yit is a vector denoting each respective conflict variable, and yit-1 its lag; tzit denotes whether a grid cell is in the Sahara-Sahel transition zone during a given month t within a given year, ndit-1 denotes the one-month lag of average vegetation health (NDVI) values for a given cell-month, and tzit X ndit-1 is our interaction term. nlit and popitare our controls, capturing (logged) nighttime light and population densities in a given cell during a given year; τt is the time trend, mt are fixed effects by month, ωj are fixed effects by country, accounting for all country-level issues and confounders that are constant over time; and εi denotes heteroskedasticity-consistent robust standard errors (Liang-Zeger) clustered by grid cell.

Table A1: Determinants of Violence against Civilians in Africa

About the Authors

Britt Koehnlein is a PhD candidate in Political Science at Indiana University. Her research focuses on civil conflict, violence against civilians, non-state actors, disease epidemics, and natural disasters as well as the downstream effects of epidemic and pandemic outbreaks.

Ore Koren is an Assistant Professor of international relations and methodology in the Department of Political Science, Indiana University, Bloomington, where he won the Outstanding Junior Faculty Award (2022). Koren completed his PhD at the University of Minnesota, where he also obtained a MSc in Applied Economics. Within international relations, his research has involved innovative approaches to studying the causes of civil conflict, with an emphasis on how environmental pressures shape patterns of political violence. Koren’s work attracted the support of the National Science Foundation, the Henry Frank Guggenheim Foundation, the Dickey Center at Dartmouth College, and the United States Institute of Peace, among others.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the reviewers, editors, and anyone else whose feedback has helped to improve this report. The authors would also like to recognize Justin Schon for his important advice and help throughout the entire process.

Notes

- 1Benjamin E. Bagozzi, Ore Koren, and Bumba Mukherjee, “Droughts, Land Appropriation, and Rebel Violence in the Developing World,” Journal of Politics 79, no. 3 (2017): 1057–1072, https://doi.org/10.1086/691057; Tobias Ide, Anders Kristensen, and Henrikas Bartusevičius, “First Comes the River, Then Comes the Conflict? A Qualitative Comparative Analysis of Flood-related Political Unrest,” Journal of Peace Research 58, no. 1 (2021): 83–97, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343320966783.

- 2Justin Schon and Ore Koren, “Introducing AfroGrid, a Unified Framework for Environmental Conflict Research in Africa,” Scientific Data 9, no. 1 (2022): 116, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01198-5.

- 3Nina Græger, “Environmental Security?,” Journal of Peace Research 33, no. 1 (1996): 109–116.

- 4Karin Dyrstad and Solveig Hillesund, “Explaining Support for Political Violence: Grievance and Perceived Opportunity,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 64, no. 9 (2020): 1724–1753, https://doi-org/10.1177/0022002720909886; Randolph M. Siverson and Harvey Starr, The Diffusion of War: A Study of Opportunity and Willingness (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1991).

- 5Schon and Koren, “Introducing AfroGrid.”

- 6Barry Buzan, Ole Wæver, and Jaap de Wilde, Security: A New Framework for Analysis, Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1998; Græger, “Environmental Security?”

- 7Jason Seawright and John Gerring, “Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research: A Menu of Qualitative and Quantitative Options,” Political Research Quarterly 61, no. 2 (2008): 294–308.

- 8Neela Banerjee, “Climate Change Will Increase Risk of Violent Conflict, Researchers Warn,” Inside Climate News, June 13, 2019, https://insideclimatenews.org/news/13062019/climate-change-global-security-violent-conflict-risk-study-military-threat-multiplier/; A. Evans, Resource Scarcity, Climate Change and the Risk of Violent Conflict 2010, Washington, DC: World Bank. © World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/9191 License: CC BY 3.0 IGO, 24; Elisabeth A. Gilmore and Halvard Buhaug, “Climate Mitigation Policies and the Potential Pathways to Conflict: Outlining a Research Agenda,” WIREs Climate Change 12, no. 5 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.722; Malin Mobjörk, Florian Krampe, and Kheira Tarif, Pathways of Climate Insecurity: Guidance for Policymakers, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), 2020, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2020-11/pb_2011_pathways_2.pdf; Robert Muggah and José Luengo Cabrera, “The Sahel Is Engulfed by Violence. Climate Change, Food Insecurity and Extremists Are Largely to Blame,” World Economic Forum, 2019, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/01/all-the-warning-signs-are-showing-in-the-sahel-we-must-act-now/; Kirby Reiling and Cynthia Brady, Climate Change and Conflict: An Annex to the USAID Climate-Resilient Development Framework, United States Agency for International Development (USAID), February 2015, https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1866/ClimateChangeConflictAnnex_2015%2002%2025%2C%20Final%20with%20date%20for%20Web.pdf.

- 9Hanne Fjelde and Lisa Hultman, “Weakening the Enemy: A Disaggregated Study of Violence against Civilians in Africa,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 58, no. 7 (2014): 1230–1257, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002713492648; Ore Koren and Benjamin E. Bagozzi, “Living Off the Land: The Connection between Cropland, Food Security, and Violence against Civilians,” Journal of Peace Research 54, no. 3 (2017): 351–364, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343316684543.

- 10Evans, Resource Scarcity; Muggah and Cabrera, “The Sahel Is Engulfed by Violence”; United Nations (UN), “Conflict, COVID, Climate Crisis, Likely to Fuel Acute Food Insecurity in 23 ‘Hunger HHotspots,’ ” July 30, 2021, https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/07/1096812.

- 11Michael Mason, “Climate Insecurity in (Post)Conflict Areas: The Biopolitics of United Nations Vulnerability Assessments,” Geopolitics 19, no. 4 (2014): 807, https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2014.903393.

- 12Note: Ide, Kristensen, and Bartusevičius, “First Comes the River, Then Comes the Conflict?”

- 13Halvard Buhaug, Scott Gates, and Päivi Lujala, “Geography, Rebel Capability, and the Duration of Civil Conflict,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 53, no. 4 (2009): 544–569, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002709336457; Paul Collier and Anke Hoeffler, “Greed and Grievance in Civil War,” Oxford Economic Papers 56, no. 4 (2004): 563–595, https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpf064; Benjamin Crost and Joseph H. Felter, “Export Crops and Civil Conflict,” Journal of the European Economic Association 18, no. 3 (2020): 1484–1520, https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvz025; Macartan Humphreys, “Natural Resources, Conflict, and Conflict Resolution: Uncovering the Mechanisms,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 49, no. 4 (2005): 508–537, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002705277545; Ore Koren, “Food Abundance and Violent Conflict in Africa,” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 100, no. 4 (2018): 981–1006, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aax106; Reed M. Wood, “Rebel Capability and Strategic Violence against Civilians,” Journal of Peace Research 47, no. 5 (2010): 601–614, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343310376473.

- 14Tracy Kuo Lin et al., “Food Insecurity in the Context of Conflict: Analysis of Survey Data in the Occupied Palestinian Territory,” Lancet 398, suppl. 1 (2021): S35, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01521-X.

- 15Koren and Bagozzi, “Living Off the Land.”

- 16Note: Schon and Koren, “Introducing AfroGrid.”

- 17Raleigh et al., “Introducing ACLED: An Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset: Special Data Feature.” Journal of Peace Research 47, no. 5 (2010): 651-660. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343310378914; Sundberg and Melander. “Introducing the UCDP Georeferenced Event Dataset.” Journal of Peace Research 50, no. 4 (2013): 523-532. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343313484347.

- 18Note: Seawright and Gerring, “Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research.”

- 19United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Climate Risks in Food for Peace Geographies: Burkina Faso, 2017, https://www.climatelinks.org/sites/default/files/asset/document/20170807_USAID%20ATLAS_FFP_BurkinaFaso.pdf.

- 20Note: Anna Schmauder, Customary Characters in Uncustomary Circumstances: The Case of Burkina Faso’s Est Region, United States Agency for International Development (USAID), 2021, https://customarylegitimacy.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/2022-02/customary_legitimacy_Est_0.pdf.

- 21Sam Mednick, “Hunger Grips Burkina Faso due to Increasing Jihadi Violence,” Washington Post, April 26, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/hunger-grips-burkina-faso-due-to-increasing-jihadi-violence/2022/04/26/256f5508-c541-11ec-8cff-33b059f4c1b7_story.html.

- 22Medecins Sans Frontières, Burkina Faso: Living Conditions Worsen for Displaced People as Violence Escalates and Rainy Season Begins, July 20, 2020, https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/latest/burkina-faso-living-conditions-worsen-displaced-people-violence-escalates-and-rainy-season.

- 23United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Climate Risk Profile: Nigeria. 2019, https://www.climatelinks.org/sites/default/files/asset/document/2019_USAID-ATLAS-Nigeria-Climate-Risk-Profile.pdf.

- 24Binh Pham-Duc et al., “The Lake Chad Hydrology under Current Climate Change,” Scientific Reports 10, no. 1 (2020): 5498, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62417-w.

- 25Olalekan Waheed Adigun, “A Critical Analysis of the Relationship Between Climate Change, Land Disputes, and the Patterns of Farmers/Herdsmen’s Conflicts in Nigeria,” Canadian Social Science 15, no. 3 (2019): 76–89

- 26Adigun, “A Critical Analysis.”

- 27Note: Henry Kam Kah, “ ‘Boko Haram Is Losing, But So Is Food Production’: Conflict and Food Insecurity in Nigeria and Cameroon,” Africa Development 42, no. 3 (2017): 177–196.

- 28Note: Kah, “Boko Haram Is Losing.”

- 29Note: Halvard Buhaug, Lars-Erik Cederman, and Kristian Skrede Gleditsch, “Square Pegs in Round Holes: Inequalities, Grievances, and Civil War,” International Studies Quarterly 58, no. 2 (2014): 418–431, https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12068.

- 30Note: Courtland Adams, Tobias Ide, Jon Barnett, and Adrien Detges, “Sampling Bias in Climate–Conflict Research,” Nature Climate Change 8, no. 3 (2018): 200–203, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0068-2. The strongest predictors of violence are rarely climate-related; they tend to be a history of violence, whether there is an

- 31Note: Most econometric research (e.g., Joshua D. Angrist and Jörn-Steffen Pischke, Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion [Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009]) and political methods research (e.g., Nathaniel Beck, “Estimating Grouped Data Models with a Binary-Dependent Variable and Fixed Effects via a Logit versus a Linear Probability Model: The Impact of Dropped Units,” Political Analysis 28, no. 1 (2020): 139–145, https://doi:10.1017/pan.2019.20) argue in favor of using OLS within two-way fixed effects settings. Count models, under these conditions, could create inferential bias by omitting zero-only observations.