Executive Summary

The over-reliance of the pastoral communities of the Karamoja Cluster in the Horn of Africa on a state-centric approach to prevent atrocities against civilians by controlling the proliferation of small arms and light weapons (SALW) has spiraled into maladaptation. This approach, commonly known as “cooperate to disarm” (C2D), was designed to prevent the diversion of state-owned arms into civilians’ hands, but it has instead disrupted livelihoods and contributed to casualties. C2D is based on two premises: managing the supply and demand of the disarmament process and ensuring that the cooperating states under the Regional Centre on Small Arms (RECSA) arrangement enhance physical security and stockpile management standards.

Despite the compelling case for C2D to support disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) programs, there is increasing concern about the model’s failure to incorporate kinship1Note: This study adopts David Ronfeldt’s (1996) definition of kinship to mean, attachment, commitment, involvement and belief system anchored on principles of egalitarianism- promoting communal living, sense of social identity and belonging, hence strengthening people’s ability to integrate and co-exist. Further reference can be made to: David Ronfeldt, Tribes, Institutions, Markets, Networks: A Framework about Societal Evolution (Santa Monica: RAND 1996). networks in the Cluster’s border communities. C2D efforts to prevent atrocity crimes by disarming civilians possessing SALW have been largely unsuccessful because Cluster communities that disarmed left themselves vulnerable to attacks from communities that had not. This paper explores the importance of adopting disarmament models that align with the local order and realities and why this has proven difficult to achieve, leading border communities and local authorities to improvise their own forms of disarmament. The C2D experience provides a lesson on the limitations of state-centric approaches in resolving cross-border conflicts deeply embedded in human relations and “hard” bonds.

Even though adaptive responses to environmental change have helped communities avoid social disruption, insecurity and threats to civilians continue to persist in the Karamoja region in part due to the ongoing proliferation of small arms and light weapons. To address the unintended outcomes of the C2D model and its failure to reduce the risks of atrocities against civilians, this paper recommends the integration of kinship social networks into DDR programs. Furthermore, stakeholders within DDR programs should utilize the comparative advantages of Cluster sub-cultures to strengthen the positive adaptation strategies. As an alternative to the C2D model that has been in use for over a decade, this paper proposes that a “human-human bond” (H2HB) approach to disarming Karamoja pastoral communities should be explored.

Introduction

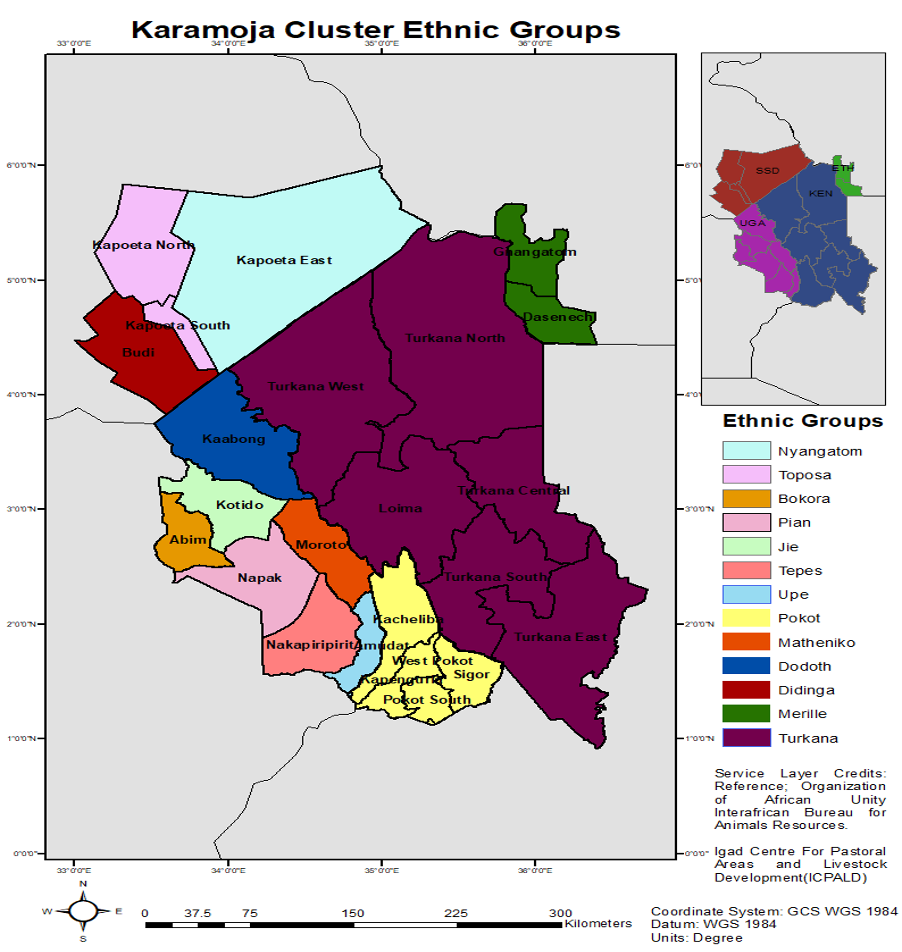

The abundance of small arms and light weapons (SALW) remains the most pressing challenge facing the pastoral communities of the Karamoja Cluster in the Horn of Africa (see Map 1), which stretches from southwest Ethiopia to northwest Kenya, the southeastern part of South Sudan, and northeast Uganda.2Note: Milas Siefulaziz and Group, “Baseline Study for the Ethiopian Side of the Karamoja Cluster,” https://www.cewarn.org/index.php/reports/archived-early-warning-reports/baseline-reports/eth-2/60-bsline-krj-eth/file. Thirteen ethnic groups sharing similar linguistic and socio-cultural ties occupy the Cluster. Note: Andy Catley, Elizabeth Stites, Mesfin Ayele and Raphael L. Arasio, “Introducing Pathways to Resilience in the Karamoja Cluster,” doi: 10.1186/s13570-021-00214-4 The community’s economic fabric includes pastoral and agro-pastoral activities and assets. To sustain stable livelihoods in the Cluster and reduce violence against civilians, various models3Note: “The Nairobi Protocol for the Prevention, Control and Reduction of Small Arms and Light Weapons in the Great Lakes Region and the Horn of Africa,” n.d., https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/research/disarmament/dualuse/pdf-archive-att/pdfs/recsa-nairobi-protocol-for-the-prevention-control-and-reduction-of-small-arms-and-light-weapons-in-the-great-lakes-region-and-the-horn-of-africa.pdf. have been tested to control SALW proliferation, the most infamous being the “cooperate to disarm” (C2D) model.

The C2D model is based on the 2002 Nairobi Declaration,4Note: “Nairobi Declaration,” n.d., https://archive.globalpolicy.org/security/smallarms/regional/nairobi.htm. which focused on preventing, combating, and eradicating the illicit manufacturing, trafficking, possessing, and use of SALW in the sub-region. The Nairobi Protocol, which provides the legal framework for the implementation of arms control in the region, was signed in April 2004.5Note: The Nairobi Protocol on the Prevention, Control, and Reduction of Small Arms and Light Weapons in the Great Lakes Region, the Horn of Africa, and Bordering States. For more details on the assessment of the status of the protocol, consult, Simone Wisotzki, “Efforts to curb the proliferation of small arms and light weapons: from persistent crisis to norm failure?” Z Friedens und Konflforsch 10 (2021): 247-271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42597-022-00073-9. The following year (2005), RECSA was established to coordinate the implementation of the Protocol.6Note: Regional Centre on Small Arms, Guidelines for establishment and functioning of National Institutions Responsible for SALW Management and Control. Available at: https://recsasec.org/index.php/page/view?id=MzE=. The Nairobi Protocol resembles the African Union’s 2013 “silencing the guns” initiative, part of realizing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Goal 16, target 4 of the SDGs7Note: “SDG Indicators,” UN Sustainable Development Goals, n.d., https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/metadata/?Text=&Goal=&Target=16.4. obliges states to “reduce illicit financial and arms flows, strengthen the recovery and return of stolen assets and combat all forms of organized crime” by 2030.8Note: United Nations, Goal 16: Promote justice, peaceful and inclusive societies. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/peace-justice/.

Disarmament in the Horn of Africa typically includes economic development and socio-cultural integration support packages under C2D among RECSA member states. C2D posits that disarmament and stability among pastoral communities can be effectively managed when development, security, and governance efforts are interconnected.9Note: “The Nairobi Protocol for the Prevention, Control and Reduction of Small Arms and Light Weapons in the Great Lakes Region and the Horn of Africa.” C2D efforts to prevent atrocity crimes by disarming civilians possessing SALW have been largely unsuccessful because Cluster communities that disarmed left themselves vulnerable to attacks from communities that had not. Moreover, military, security forces, and county administrators often failed to consult with local communities,10Note: Dominique Dye, “Arms Control in a Rough Neighbourhood: The Case of the Great Lakes Region and the Horn of Africa,” Institute for Security Studies Papers 2009, no. 179 (2009): 179, https://issafrica.org/research/papers/arms-control-in-a-rough-neighbourhood-the-case-of-the-great-lakes-region-and-the-horn-of-africa. raising inter-communal tensions and mistrust among the pastoral communities and the so-called “cooperating states.”11Note: The RECSA Cooperating states include Republic of Burundi, Central African Republic, Republic of Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, Republic of Djibouti, Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, State of Eritrea, Republic of Kenya, Republic of Rwanda, Republic of Seychelles, Federal Republic of Somalia, Republic of South Sudan, Republic of the Sudan, United Republic of Tanzania, Republic of Uganda.

Lessons from previous disarmament processes suggest that interactive disarmament efforts are more effective than militarized ones.12Note: Elizabeth Stites and Darlington Akabwai, “‘We Are Now Reduced to Women’: Impacts of Forced Disarmament in Karamoja, Uganda,” Nomadic Peoples 14, no. 2 (2010): 24–43, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43123871. Unlike military (forced) disarmament, a human relational approach to DDR is anchored on local networks, cultural connections, and kinship and has persuaded the Karamoja community to surrender more arms than the militarized approach. A study by Patrick Kachope13Note: Patrick Kachope, “Micro-Disarmament Experiences in Africa: Learning from the Karamoja Integrated Disarmament and Development Programme, Northeastern Uganda,” African Security Review 30, no. 3 (July 3, 2021): 271–89, https://doi.org/10.1080/10246029.2020.1828117. examines how the Karamoja Integrated Disarmament and Development Program enhanced coordination and trust-building among the neighboring communities in the Cluster. The policy concern has been reconciling the official militarized foreign policy approach to disarmament with a human relations approach.14Note: In this study, human relation is anchored on five pillars: local value system, kinship, social bonding, culture and norms. Such approaches would enable the United Nations and other African regional stakeholders to pursue new models of disarmament for coherent coordination in the control of arms trade and prevention of proliferation of SALW in the Horn of Africa.

Using the Intergovernmental Authority on Development’s (IGAD)15Note: Milas Siefulaziz and InterAfrica Group, “Baseline Study for the Ethiopian Side of the Karamoja Cluster” (Inter Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD) Region, 2004), https://www.cewarn.org/index.php/reports/archived-early-warning-reports/baseline/eth-2/60-bsline-krj-eth/file. Conflict Early Warning and Response Mechanism’s (CEWARN) historical data (2006-2021), this report uses an integrative literature review to illuminate the trends and patterns shaping conflict and violence. It also explores appropriate mechanisms for conducting disarmament to prevent atrocities in the Cluster. Desktop research is complemented by interviews with participants of the RECSA-organized Cross Border Leaders Conference held in Entebbe, Uganda, on March 24–25, 2021. Finally, this paper draws on ongoing research on the intertribal border markets as “factories” of conflict as well as infrastructures to address the challenges faced by fragile states16Note: Francis Onditi, “Quasi-experimental studies of tribal markets as factories of conflict and infrastructures for peace (I4P) in Kenya (production, distribution, consumption & transformation of conflict). Unpublished Research Proposal Licensed by the National Commission for Science, Technology & Innovation (NACOSTI), License No: NACOSTI/P/22/16916. April 2022. and pastoral communities in the Horn of Africa.17Note: The Karamoja Cluster ethnic groups include; the Bokora, Dessenech, Didinga, Dodoth, Jie, Matheniko, Nyangatom, Thur, Pian, Pokot, Tepeth, Topotha and Turkana. Andy Catley et al., “Introducing Pathways to Resilience in the Karamoja Cluster,” Pastoralism 11, no. 1 (November 24, 2021): 28, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13570-021-00214-4.

Trends and Warnings: Vulnerabilities and Risks in the Karamoja Cluster

At the 2021 Entebbe Cross-Border Leaders Conference, it was asserted that C2D is its preferred approach to disarmament for the Karamoja Cluster. The Cluster is geographically expansive and culturally diverse (see Map 1)18Note: IGAD, “Baseline Study for the Ethiopian Side of the Karamoja Cluster”, 2004. Available at: https://www.cewarn.org/index.php/reports/archived-early-warning-reports/baseline-reports/eth-2/60-bsline-krj-eth/file. , while also among the most fragile and conflict-prone areas in the Horn of Africa. Despite regional and international attention and substantial financial resources for controlling the proliferation of SALW in the Cluster, banditry and armed cattle rustling remain prevalent. A 2016 study into the risks associated with armed violence painted a grim picture: 34,512 armed crimes occurred in Uganda, 26,041 cases were recorded in Burundi, Kenya saw 12,877 cases, and Tanzania 9,646.19Note: “Regional Report on the Nexus Between Illicit SALW Proliferation and Cattle Rustling Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan and Uganda,” 2016. Available at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/REGIONAL-REPORT-ON-THE-NEXUS-BETWEEN-ILLICIT-SALW/8975c0308b66fd5aba494f7b78d47cd5100fae21. Most respondents in Kenya (63 percent), Ethiopia (74 percent), South Sudan (60 percent), and Uganda (58 percent) blamed the uncontrolled flow of arms in the Cluster on the activities of pastoralists, the interaction between the various communities, and the activities of national militaries and militia groups. Uncontrolled flow of small arms and light weapons among civilians can contribute to the onset of armed violence as organized groups conduct livestock raids and engage in retaliatory activities with the pretext of protecting their respective ethnic group or clans. Naturally, these ethnic groups—with similar livelihood activities, shared boundaries, and a common source of livelihood assets (see Map 1)—are likely to remain in a state of volatility as efforts to disarm are met with resistance. Thus, this study is a combination of cross-sectional and observational inquiries to highlight the failure of forced disarmament intervention.20Note: Stites and Akabwai, “‘We Are Now Reduced to Women’: Impacts of Forced Disarmament in Karamoja, Uganda.” Nomadic Peoples 14, no. 2 (2010): 24-43.

Map 1: Distribution of Ethnic Groups in the Karamoja Cluster, Horn of Africa

As Map 1 shows, the Karamoja Cluster ethnic groups are spread across arid and semi-arid agro-ecological zones, making pastoral activities the most suited form of livelihood. However, this definition is more geographic rather than ethnic.21Note: Thus, this category includes the Merille of Ethiopia, the Pokot of Kenya and Didinga of South Sudan; The Karamojong are further sub-divided into; the Pian, the Upe, the Bokora, the Tepes, the Matheniko, the Jie and the Dodoth. “Karamojong Cluster Harmonisation Meeting” (Karamojong Cluster Harmonisation Meeting, Lodwar, Kenya: Organization of African Unity Interafrican Bureau for Animal Resources, 1999), https://fic.tufts.edu/wp-content/uploads/AU-IBAR-Lodwar-Meeting.pdf. Over the years, communities in the Karamoja Cluster have experienced conflict incubation, including state fragility, governance gaps, weak state-periphery relations, armed violence, underdevelopment, illegal arms marketing, and bouts of violent livestock raiding.22Note: Siân Herbert and Izzy Birch, “Cross-Border Pastoral Mobility and Cross-Border Conflict in Africa: Patterns and Policy Responses,” Evidence Synthesis (International Development Department, College of Social Sciences: GSDRC, January 2022), https://gsdrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/2021-12-09_GSDRC-Pastoralist-Mobility-FINAL2-1.pdf. However, the Cluster exhibits varied political and conflict contexts. While some areas enjoy relative peace and stability, persistent livestock raiding and widespread armed violence rage across other areas of the Cluster.

The exposure of the community to risk factors such as poverty, social marginalization, and exclusion reinforces this culture of violence. The negative impact of this cyclic culture of violence on people’s livelihoods is particularly chronic in the Horn of Africa because the community residing in this arid and semi-arid ecosystem is dependent on pastoralism and use small arms and light weapons to defend their livestock. In addition to the growing proliferation of SALW and atrocities resulting from armed livestock raiding, a significant impediment to sustainable peace in the Karamoja Cluster has been the failure to devise an appropriate mechanism for disarming civilians by the concerned states. Everyday life23Note: The everyday life of the communities occupying the Karamoja Cluster defines how and where they draw water, where they take their livestock for grazing, how they socialize and how safe they felt in their own homesteads. of a Karamojan is, unfortunately, defined by civilians’ access to SALW.24Note: Andy Catley, Elizabeth Stites, Mesfin Ayele and Raphael L. Arasio, ‘Introducing pathways to resilience in the Karamoja Cluster. Pastoralism: Research, Policy and Practice (2021).

The trend points to the multifaceted nature of factors sustaining the Karamoja communities’ vulnerabilities. Although the main challenge facing the pastoral community is the continued threat of insecurity emanating from SALW, it is clear there is a need to recognize the problem’s complex nature, including the persistent experience of environmental change, economic inequality, migratory behavior, and the risks associated with a culture of gun violence.

Environmental Change and Economic Inequalities

Environmental change and economic inequality have a deep-rooted, multifaceted connection with armed conflict. The effects of environmental change are evident in degrading grazing lands and changing rainfall patterns, leading to pasture and water scarcity for livestock. The pastoral communities must rely on kinship networks to tackle livestock management challenges, livestock diseases, reduced available land for water and feeds, and socio-economic marginalization. Increased drought frequency motivates cattle raids to replenish herds. In other words, the livelihood activities of pastoral communities are bound to the environment.25Note: Kennedy Mkutu, “Pastoral Conflict and Small Arms: The Kenya-Uganda Border Region” (International Development Department, College of Social Sciences: GSDRC, 2003), https://www.saferworld.org.uk/downloads/pubdocs/Pastoral%20conflict.pdf.

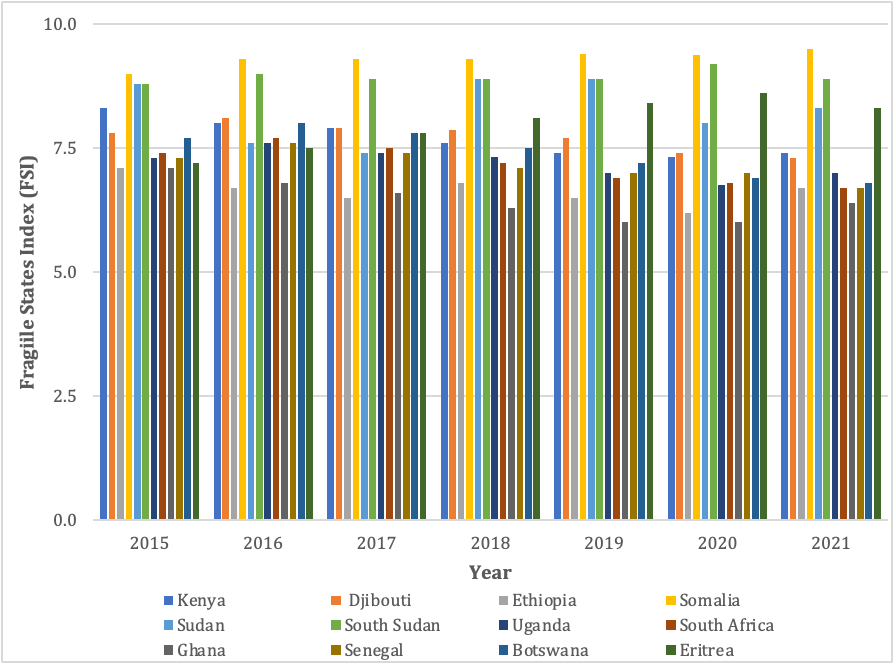

A recent predictive study based on the Standardized Precipitation Evaporation Index shows that from 1979 to 2019, the Horn of Africa’s drought frequency and intensity increased significantly.26Note: Xue Han et al., “Attribution of the Extreme Drought in the Horn of Africa during Short-Rains of 2016 and Long-Rains of 2017,” Water 14, no. 3 (2022), https://doi.org/10.3390/w14030409. This has kept the Karamoja cluster and its estimated population of 1.4 million Note: “Resilience Analysis of Karamoja (Uganda)” (Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, January 15, 2018), https://www.fao.org/3/i8365en/I8365EN.pdf. one of the poorest regions, recording the worst human development indicators (HDI) in key areas, including poverty. This poor HDI is reflected in the ever-deteriorating Fragile State Index. Four27Note: The four IGAD member states located in the Karamoja Cluster include Ethiopia, Kenya, South Sudan, and Uganda. More information on the geography and culture of the Karamoja Cluster can be found here: https://resilience.igad.int/clusters/igad-cluster-1-karamoja-cluster/ of the IGAD member states in the Karamoja Cluster continue to experience deteriorating economic conditions, with unsuccessful responses due to group inequalities, illicit capital transactions, and money laundering (see Figure 1).

In the Horn of Africa, fragility is worsening because of competition over cross-border resources, climate shocks, ethnic strife across borders, and illegal cross-border trade that threatens livelihoods and stability. The increasing fragility can also be attributed to heightened vulnerability emerging from problems of political economy.

Figure 1: Economic Inequalities in the Karamoja Cluster Horn of Africa Compared to the Progressive SADC and ECOWAS States

The responses to deteriorating socio-economic conditions by the Horn’s governments are weak, leading to extreme vulnerabilities among pastoral communities in the Cluster. The per capita livestock ownership in the Karamoja Cluster is closely related to environmental economic stress. Although the income of the pastoral communities in the Cluster has been associated with positive economic growth, the review of CEWARN historical data shows declining livestock ownership per capita. The driving force of this trend is the observed economic inequality. The systematic review reveals that the wealthiest households in the Cluster hold the largest share of livestock per capita. As illustrated in Figure 1 above, uneven access to economic opportunities significantly contributes to the current increase in state fragility throughout the Horn.

Unsurprisingly, the negative effect of inequality in the Horn of Africa concurs with a previous study by the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), which showed that 47 percent of households in the Cluster owned only 1.2 Tropical Livestock Units (TLU) per capita, against the global threshold of 3.3 TLU per capita for viable agro-pastoral assets.28Note: “Livestock and Poverty in Karamoja: An Analysis of Livestock Ownership, Thresholds, and Policy Implications” (Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, January 31, 2019), https://www.fao.org/in-action/kore/publications/publications-details/en/c/1178860/. The state-centric approach to managing land resources in the Karamoja Cluster remains retrogressive. In Kenya, for example, nearly 25 percent of land in the Cluster is locked up under exclusive mineral exploration and location licenses for oil discoveries in Turkana County. This suggests that land and livelihoods are at risk and, as a result, increases the risk of gun violence because the cost of violence to resist the state is less than the cost of losing land.29Note: Regional Centre on Small Arms, A Report of Analysis on Armed Crimes in East Africa Community Countries (Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda). (Regional Centre on Small Arms, 2016), https://books.google.com/books?id=vuEcxwEACAAJ. The implementation of the 2002 Nairobi Declaration has been sluggish, making the control of illicit small arms and light weapons unviable. The international communities’ approach is to “use development cooperation as an incentive for peace.”30Note: “Report of the IGAD Regional Workshop on the Disarmament of Pastoralist Communities” (Entebbe: Conflict Early Warning and Response Mechanism (CEWARN), May 28, 2007), https://www.cewarn.org/index.php/reports/special-reports/2-igad-regional-workshop-on-the-disarmament-of-pastoralist-communities/file. It involves channeling more development funds to areas of the Cluster where local leaders have shown commitment to peaceful resolutions to conflicts to stop inter-clan cattle raiding and other crimes. It has not been successful in integrating environmental change and seasonality-related risks to address the problem of possession of arms by civilians. Yet, the historical analysis reported in this study shows sufficient cross-pollination between seasonal changes and the occurrence of conflict or protest demonstrations in the area.

The seasonal pattern implies that the availability of water and pasture for the communities is strained by December. Indeed, December and January are the riskiest months regarding livestock raids due to clashes between the pastoralist and farmers. One of the county officials from the border town of Torit in South Sudan who attended the 2021 Entebbe Leaders Conference said:

“In Torit County, cattle raids are perceived to occur on a weekly basis. The report estimates a death toll resulting from cattle rustling at 15-20 per month. It is typical in this area that clashes occur only after cattle are discovered missing and attempts are made to recover them and during subsequent revenge attacks”.

An interview with Deputy Planning Officer, Eastern Equatoria State, Torit County, March 24, 2021

Proliferation of Small Arms and Cyclical Armament of Civilians

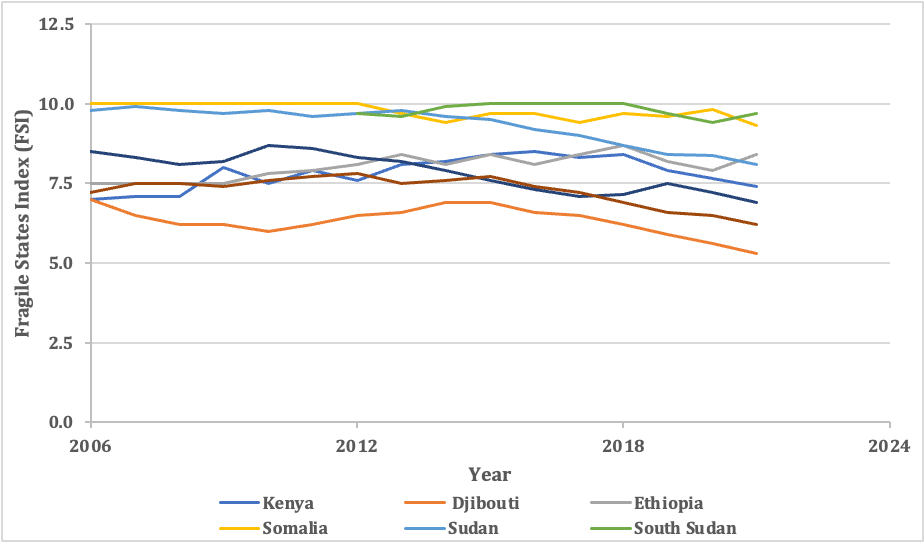

The proliferation of small arms and the cyclic armament of the civilian population in the Karamoja Cluster is attributed to the deteriorating security apparatus (see Figure 2). A number of case studies find that the risk of insecurity in the Horn of Africa increases with the deteriorating weather conditions such as drought, and that this variation in the livelihood asset base for the pastoral communities can cause irregular migration exposing them to further vulnerabilities.31Note: Janpeter Schilling, Francis Opiyo and Jurgen Scheffran, “Raiding pastoral livelihoods: Motives and effects of violent conflict in North-Western,” Pastoralism 2, no. 25 (2012): 1-16: Also see, Mark O’Keefe, “Chronic crises in the Arc of insecurity: a case study of Karamoja,” Third World Quarterly 31, no. 8 (2010): 1271-1295. These cyclic crises, including the proliferation of SALW, persist mainly in ungoverned spaces.32Note: Ungoverned space is the physical or non-physical area where there is absence of state capacity or political will to exercise control. Angel Rabasa et al., Ungoverned Territories: Understanding and Reducing Terrorism Risks, 1st ed. (RAND Corporation, 2007), https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7249/mg561af.

It is no wonder local governments in the Horn of Africa supply 50 percent of the weapons in the region, with all the neighboring countries, including Kenya, Sudan, Tanzania, Ethiopia, and Uganda, having ammunition and manufacturing capabilities.33Note: “Presentation at RECSA Cross Border Leaders Conference on Resources Management, Conflict Management and SALW Proliferation Control” (RECSA Cross Border Leaders Conference on Resources Management, Conflict Management and SALW Proliferation Control, Entebbe, March 24, 2021), https://www.att-assistance.org/activity/recsa-cross-border-leaders-conference-resources-management-conflict-management-and-salw. Illegal arms business in the Horn of Africa includes the value chain of manufacturing, smuggling, leakages from police, and theft carried out at borders. Within the Fragile States Index (FSI) framework, security apparatus indicators measure the security related threats to a state or community, including, battle related deaths, rebel movements, activities of the deep state, coups, terrorism and gangsterism.34Note: Fund for Peace, Measuring fragility: Risk and vulnerability in 179 countries. Washington D.C. https://fragilestatesindex.org/. With the proliferation of SALW in the Horn of Africa, the main form of security threats is the organized criminal gangs and privately sponsored militias, who, over the years, have commercialized cattle raiding through what some scholars have coined, “rise of ‘traiders’ in Karamojong Cluster.”35Note: Dave Eaton, “The rise of traider: the commercialization of raiding in Karamoja,” Nomadic Peoples 14, no.2 (2010): 106-122. Various stakeholders have tried to prevent this illicit arms sale without causing further harm, but as Figure 2 shows, countries in the Cluster continue to record the worst security status on the FSI. From 2020 to 2021, the FSI for the countries in the Horn deteriorated. The illicit arms trade and the consequent decrease in security across the Cluster indicate increased organized crime and private militia groups that thrive on political instability and illegal markets (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Security Apparatus in the Horn of Africa

The possession of arms alone, however, is not a predisposing factor for insecurity, but it does increases the likelihood of gun violence and livestock raiding. Interestingly, despite the increasing C2D disarmament activities, violent livestock raiding has continued. This illustrates cooperating states’ “unwillingness” to prevent atrocities through coordinated disarmament. During the 2021 Cross-Border Leaders’ Conference, organized by RECSA, the delegates were reminded that civilians, insurgents, and armed communities in the Horn possess thousands of illegal weapons. According to delegates, these communities’ main challenge was the lack of an effective disarmament mechanism. One of the delegates attending the 2021 Entebbe leaders Conference said:

“Disarmament must be seen as part and parcel of the human relations and development processes and not as a one-off event. It must be approached from a human security angle, considering all aspects of security physical, economic, safety, environment, ecology, culture, economy, politics, and above all, human relations. The process should be incorporated into the broader regional and global strategies for promoting sustainable development and peace as well as prevention of all forms of atrocities”.

Executive Secretary of RECSA, Lt. Gen. Badreldin Elamin Abdelgadir, March 24, 2021

Indeed, the efforts to address the proliferation of SALW and decrease the chances of atrocity crimes must encompass different facets of human security, including environmental adaptation. To this end, communities in the Cluster have developed strategies to mitigate the impact of environmental change. These include water harvesting and conservation. On the Ugandan side of the Cluster, the Ministry of Water and Environment has developed comprehensive agro-forestry plans to improve water catchment capabilities. Manifestations of reported resilience include a sense of agency, social connectedness, and livelihood diversification. However, part of the reason for the lack of effective C2D implementation is the over-reliance on a top-down approach. Although this approach has enforced cooperation and commitment among the participating states, the lack of accountability mechanisms confirms the “inability” and “unwillingness” to stop atrocities against civilians by cattle rustlers.

This unstable security situation persists in the Cluster, and since November 2020, cattle raiders have killed about 150 people. 36Note: LIam Taylor, “In Uganda’s Karamoja, Rampant Rustling and a Militarised Response as Violence Returns,” The New Humanitarian, January 26, 2022, https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news-feature/2022/1/26/Uganda-Karamoja-cattle-rustling-militarised-violence-returns. Millions of small arms and light weapons in circulation in Africa make violence more lethal and atrocious.37Note: Ochieng Adala, “Nonproliferation in Eastern Africa,” Southern Flows: (Stimson Center, 2014), JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep11012.7.

Circular Migratory Behavior among Pastoral Communities

The circular migratory behavior among the Karamoja ethnic groups, linked to alternating wet and dry seasons and marked by internal and external migration among the pastoral communities for water, food, and pasture for their livestock, reflects nature, patterns of livelihood, and adaptation strategies. As part of the culture, the Karamoja community’s kinship networks evolved into a communal lifestyle known as stock associates.38Note: Padmini Iyer, “Friendship, Kinship and Social Risk Management Strategies among Pastoralists in Karamoja, Uganda,” Pastoralism 11, no. 1 (December 2021): 24, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13570-020-00182-1. This paper adopts David Ronfeldt’s definition of kinship to mean“attachment, commitment, involvement and belief system anchored on principles of egalitarianism- promoting communal living, sense of social identity and belonging, hence strengthening people’s ability to integrate and co-exist.”39Note: David Ronfeldt, Tribes, Institutions, Markets, Networks: A Framework about Societal Evolution (Santa Monica: RAND 1996). An archival review reveals that, during periods of severe drought, Karamojong children would be sent to their relatives or friends (stock associates) to live and work and return when favorable conditions existed.

The kinship associations help the community share familial, village, and clan connections with their Cluster neighbors, which is helpful during migration. While on the move, pastoralists sustain their livelihood by selling essential household goods and making crafts. Challenges also arise when they settle in a place. Often characterized as allogenes (“outsiders”) by the more settled locals, the migratory people face harassment, verbal and physical abuse, and lack essential services and adequate housing. When these conditions were evaluated against the FSI on human flight and brain drain, all the states within the Cluster recorded sluggish improvement on this indicator. Although 2006 to 2021 trends indicate increased circular migration within the Cluster, 2018 to 2021 recorded a significant drop in displacements, suggesting improvement in opportunities and positive adaptation strategies such as livelihood diversification.

Despite the challenges associated with circular migration among pastoral communities, they have developed adaptive strategies for survival along migration corridors. However, the negative impacts of recurring internal conflicts created by internally displaced people, state securitization of refugees at the borders, and lack of sustained economic recovery policy and strategy within C2D remain. The failures of C2D have intensified the insecurity in the Karamoja Cluster. While African armed forces and law enforcement agencies have fewer than 11 million weapons, civilians and non-states actors hold an estimated 40 million firearms.40Note: Pamela Machakanja and Chupicai Shollah Manuel, “Southern Africa: Regional Dynamics of Conflict and the Proliferation of Small Arms and Light Weapons,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Small Arms and Conflicts in Africa (Springer, 2021), 983–1001 This illustrates how challenging it is to achieve efficient disarmament.

This, however, does not necessarily imply that human mobility in the Cluster inevitably leads to internal conflicts or atrocities. Structured mobility, such as circular migration, can reinforce positive adaptation strategies that mitigate the impacts of seasonal resource stress and social attachment among border communities.41Note: Laura Freeman, “Environmental Change, Migration, and Conflict in Africa: A Critical Examination of the Interconnections,” The Journal of Environment & Development 26, no. 4 (2017): 351–74. Studies have attributed the difficulties in disarmament to the pervasive nature of internal security, which does not recognize the importance of arms in communal defense against armed criminal and insurgent groups.42Note: Philip Stibbe, Challenges to disarmament, demobilization and reintegration. E- International Relations, September 2012. Available at: https://www.e-ir.info/2012/09/02/challenges-to-disarmament-demobilisation-and-reintegration/#_ftnref8. In the current study, key informants from the Entebbe Leaders’ Conference alluded that the C2D model had been found to weaponize social networks. The lack of trust between the authorities and local communities within the C2D framework has led the former to arm proxy groups against the migrating pastoralists. This is what I characterize in this study as “arming to disarm” (A2D).

However, pockets of the Cluster population have resisted this approach. Among the Karamojong of Uganda, there exist multilevel strategies of kinship networks, including self-organizing through the establishment of clan-based vigilante groups and local peace committees based on the community’s day-to-day migratory lifestyle.

The Pervasive Culture of Gun Violence and Group Grievances

The culture of gun violence and group grievances are connected to the problem of SALW in the Karamoja Cluster. The Karamoja communities have a reputation for conflicts over livestock and pastoral resources.43Note: Kabiito Bendicto, “Culture, Resources and the Gun in the Violent-Conflict Expression.” Available at: https://ir.umu.ac.ug/handle/20.500.12280/2860. Two perspectives account for the gun violence and the subsequent group grievances. First, a materialistic perspective views cattle raiding as a wealth-creating endeavor. The evolution of an illegal SALW market and the need for survival and wealth accumulation have perpetuated gun violence in the Cluster.44Note: James E. Burroughs and Eric Rindfleisch, “Materialistic and Well-being: A Conflict Values Perspective.” Journal of Consumer Research 29, no. 3 (2002), 348-370. Second, the pastoral culture is based on traditional values and practices.45Note: Johan Galtung, “Violence, Peace, and Peace Research,” Journal of Peace Research 6, no. 3 (1969): 167–91. The community’s resistance to change is embedded in these livelihood structures. Although deep-rooted cultural structures can pose a challenge to change, the silver lining is that such structures form the bedrock of family and clan kinship, which is needed for building trust between the local community and national authorities.

Some delegates at the 2021 Entebbe conference blamed the lack of community interactive disarmament strategy and ungoverned spaces in the Cluster for the proliferation of SALW. The Karamoja people of Uganda call it Ng’amatidae,which means “self-protection.” It is invoked when the state has failed to provide security. Self-protection is essential to the pastoral community structure, which views warriors as strong community defenders. One of the delegates in the 2021 Entebbe Leaders Conference said:

“Maturity, among the Karamojong, meant the capacity to show that you’re strong and resilient in the harsh socio-ecological setup of the sub-region, traits attainable through risky fights with humans and wild animals. In the common outlook, a good shepherd is a good executor of violence, as a necessary trait for survival”.

Interview with Christine Akot, Karamoja District, Uganda, March 24, 2021

Given that the discussed factors46Note: The five factors driving vulnerability in the Karamoja Cluster include environmental change and economic inequalities, cyclic armament, circular migratory behavior, and gun violence. driving vulnerability in the Karamoja Cluster will be a key agenda item of any future intervention to address the problem of proliferation of SALW, developing the social infrastructure for enhancing the resilience of the pastoral communities is crucial. However, the lack of an effective mechanism for comprehensive disarmament will aggravate Cluster vulnerabilities. Environmental change, population displacement, population growth, and restrictions on mobility under the C2D model are likely to increase competition over resources and lead to further gun violence.

The response to these challenges has evolved along gender lines. On the one hand, men have prioritized pasture primarily to sustain livestock wealth. On the other hand, women have prioritized tree planting and water harvesting because they are sources of household income and food. With the economic shocks, worsening state fragility, and increasing environmental resource stress, the role of women in the Karamoja Cluster is changing. In Moroto on the Ugandan side of the Cluster, livelihood patterns are changing because of the loss of men from armed cattle raiding,47Note: Liam Taylor, “In Uganda’s Karamoja, Rampant Rustling and a Militarised Response as Violence Returns.” strengthening women’s independence and social standing as they become breadwinners. This, in turn, has led to increased domestic violence due to declining socio-economic opportunities available for men. A study by Elizabeth Stites48Note: Elizabeth Stites, “Gender in Light of Livelihood Trends in the Karamoja Cluster” (KRSU Conference, Moroto, Uganda, 2019), https://karamojaresilience.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/14ec3c_090702f8afd44da8b1d695441ee92335.pdf. shows that women have assumed larger responsibilities in labor, cultivation, and sale of livestock products, with some even venturing into non-livestock sectors such as road construction.

Besides environmental change, gender policies, norms, and values have also evolved, with more women becoming economically empowered through positive adaptation strategies and livelihood diversification.49Note: Francis Onditi and Josephine Odera, Understanding Violence against Women in Africa: An Interdisciplinary Approach (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021). This may elevate the role of women from simply “participating” in development to owning and managing land resources.50Note: Raphael Lotira Arasio, Andy Catley, and Mesfin Ayele, “Rapid Assessment of COVID-19 Impacts in Karamoja, Uganda,” Technical Report for the Karamoja Development Partners Group (Uganda: Kampala Resilience Support Unit-USAID/Uganda, August 2020), https://karamojaresilience.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/tufts_2037_krsu_covid_19_v2_online-2.pdf. This is already a reality in the Cluster; more women are engaged in trading activities at the market, and more girls are attending school. This adaptation to environmental change and shifting gender roles point to the need for a comprehensive approach beyond the militaristic C2D model.

In the following section, this study evaluates the C2D model as applied in the Karamoja Cluster.

Shortcomings of C2D in the Karamoja Cluster

The global model for controlling SALW remains fragmented and incoherent. 51Note: Randy Rydell, “The Guterres Disarmament Agenda and the Challenge of Constructing a Global Regime for Weapons,” Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament 3, no. 1 (January 2, 2020): 21–40, https://doi.org/10.1080/25751654.2020.1764259. Moreover, in SALW “black spot” areas such as the Karamoja Cluster, there is a general observation that environmental stress leads to maladaptation syndromes, such as “arming to disarm” (A2D).

The lack of an equitable approach to disarmament among the Karamoja Cluster communities is worsened by illegal arms markets and the lack of transparency in applying C2D. As noted earlier, RECSA’s mandate is to build the capacity of member states to prevent, control, and reduce the proliferation of illicit SALW. Three main objectives guide RECSA’s work:

- Prevent, combat, and eradicate illicit SALW.

- Promote and facilitate information sharing.52Note: The 2004 Nairobi Protocol for the Prevention, Control and Reduction of Small Arms and Light Weapons in the Great Lakes Region, the Horn of Africa and Bordering States, outlines the nature of information to be shared among the RECSA member states to include control of SALW, seizures, forfeitures, distribution, collection and destruction of SALW. “Comparative Analysis of Global Instruments on Firearms and Other Conventional Arms: Synergies for Implementation” (Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, April 2016), https://www.unodc.org/documents/firearms-protocol/ComparativeAnalysisPaper.pdf.

- Promote cooperation at the international and sub-regional levels.

RECSA was established on the understanding that disarmament is key to regional inter-state cooperation and maintaining peace and security. Although RECSA has achieved several milestones through C2D, including establishing a National Focal Point for coordinating member states and expanding the horizon to address human security problems associated with SALW, none of its objectives take the contribution of the community’s unique kinship structures and networks into account when addressing the proliferation of SALW.53Note: Nairobi Protocol for the Prevention, Control and Reduction of Small Arms and Light Weapons in the Great Lakes Region and Horn of Africa, Article 8, Page 7, Article 9, page 8. Close collaboration between government agencies and local communities increases the trust needed to seize illicit arms and build resilience to prevent atrocities.54Note: Andy Catley, Elizabeth Stites, Mesfin Ayele and Raphael L. Arasio, “Introducing Pathways to Resilience in the Karamoja Cluster,” doi: 10.1186/s13570-021-00214-4 C2D emphasizes a militarized approach to tackling disarmament using local militias and auxiliary forces. This has proved counterproductive because it leads to skewed disarmament and increased fears and tensions, which further curtails human mobility. This controlled movement of people and goods changes the nature of raiding, with raiders operating outside the official road network. This spiral leads to less effective surveillance and policing.

Governments and the international community operating in Karamoja Cluster act within the principles of the Nairobi Protocol on preventing, controlling, and reducing the proliferation of illicit SALW based on C2D. The concerned governments have initiated both formal (i.e., disarmament and reintegration activities are coordinated by government agencies) and informal (i.e., engagement of local opinion shapers, village elders and other non-state actors) interventional strategies to demobilize the local community of SALW. Despite these efforts, however, the changing livelihood dynamics, especially the growing gap in livestock ownership between rich and poor households, the shift from large-scale violent cattle raids to domestic violence has led to differing views on the approaches to disarmament.55Note: Elizabeth Stites and Kimberly Howe, “From the border to the bedroom: changing conflict dynamics in Karamoja, Uganda,” The Journal of Modern African Studies 57, no. 1 (2019) : 137-159. The clash of approaches has reinforced the cyclic phenomenon of A2D when state and local administrators supply weapons to local militias and community warriors on one side of the border to tackle security threats from elsewhere within the Cluster. This inequitable approach to disarmament raises tensions and encourages livestock raiding and the forming or joining of armed groups.56Note: The New Humanitarian, In Uganda’s Karamoja, rampant rustling and a militarised response as violence returns. https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news-feature/2022/1/26/Uganda-Karamoja-cattle-rustling-militarised-violence-returns.

When interviewed, a delegate from Uganda during the Entebbe Leaders Conference reiterated that:

“While the benefits of ‘cooperation-to-disarm’ normally outweigh the benefit of livestock raiding when resources are abundant, the relative value of cooperate-to-disarm decreases when there is drought, less pasture, and scarce water available for the livestock. On this basis, I challenge RECSA Member States to develop a regional grand plan to strengthen resilience of cross-border communities, especially during drought seasons, through a number of initiatives, including regulating cross-border livestock markets, undertake regular electronic livestock branding, and establishing more border posts to allow ease of movement of people and goods”.

Interview with Maj. Martha D. Asiimwe- a delegate from Uganda, March 24, 2021

Archival data reveals that the so-called “cooperating states” used militaristic tactics such as cordon-and-search operations to disarm the pastoral communities, surrounding villages and imposing curfews while at searching homes for firearms. This operation succeeded in confiscating weapons, but only in the short term. Uganda’s UPDF in Moroto and the Kenya Defence Force (KDF) in West Pokot, particularly, used excessive force, and violated human rights. A participant in the 2021 Entebbe Leaders Conference said:

“Given the violations (killings, torture, arbitrary detention, destruction of property and arming of opponents), we, the pastoral community, have lost trust in the police and local administrators”.

Interview with Christine Akot- a delegate from Uganda, March 24, 2021

The continued militarized joint cross-border disarmament operations in the Karamoja Cluster reinforces the notion of A2D. Another factor reinforcing A2D is the incongruous link between international cross-border migrations and internal Karamojong mobility. Given the blood kinship and cultural connection among the Cluster communities, informal multiple-country circular migrations outside government control exist. However, the formal structures under the framework of C2D limit free mobility for several reasons: trade irregularities, export of terrorism, and the need to maintain law and order. These formal regulations have done little to prevent a resurgence of conflicts and raiding commercialization, with some raids far from the international borders, in the Cluster.

C2D has rendered the Karamoja community powerless, inhibiting its efforts to achieve complete disarmament. Key attendees at the 2021 Entebbe Leaders Conference believed that the joint disarmament operation could not monitor the supply side of disarmament. As a result, weapons are an indispensable means to defend livestock and access water and pasture for livestock. The skewed disarmament left a power imbalance between communities that disarmed vs. those that have not. On this note, some countries in the Cluster, such as Uganda and Kenya have conducted successful community-based disarmament by providing alternative livelihoods under the Karamoja Integrated Disarmament and Development Project (KIDDP), however, there still exist cases of fatal sectarian violence from cattle rustling that the concerned stakeholders are yet to mitigate.57Note: Republic of Uganda, Office of the Prime Minister: Ministry for Karamoja Affairs: Karamoja Integrated Development Plan 2, 2021. Similarly, a cross-sectional study conducted by RECSA in Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan, and Uganda showed how groups still possessing weapons raided those who did not, leaving the former fearful and powerless.58Note: Regional Centre on Small Arms, RECSA, Regional report on the nexus between illicit SALW proliferation and cattle rustling : Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan and Uganda. https://recsasec.org/uploads/documents/162247616.pdf. A lack of investment by governments in the region in infrastructure—which could contribute to strengthening security—has resulted in the proliferation of SALW.59Note: Leff, Jonah. “Pastoralists at War: Violence and Security in the Kenya-Sudan-Uganda Border Region.” International Conflict and Violence 3, 2 (2009), 188-203, 193. The study pointed out weak legislation, inadequate state presence, and porous borders sustaining cross-border cattle rustling. In most cases, the state apparatus relied on local informers to know about changes in pastoralists’ behavior. However, this approach proved ineffective in preventing raiding because interethnic cynicism led to heightened tensions among the neighboring clans. One of the Kenyan government officers attending the 2021 Entebbe Leaders Conference argued:

“The predominance of the nation-state as the center of power neglects the role of human relations in addressing the most pressing problem of Karamoja — proliferation of small arms and light weapons. Yet, the human relations/social bonding is key in understanding the flow of conflict within the transnational networks, and hence, developing peace pathways should consider salient kinship relationships: clans, extended families, cross-border homes, and nuclear families”.

Interview with an officer from the Ministry of Interior and Coordination- Kenya, March 24, 2021

When states were unable to detect raiding, confiscate illegal weapons, or mobilize the local community into voluntary disarmament, they blamed this failure on the “unwillingness” of the communities. Worse still, the state then supplied weapons to proxy groups to fight these local community warriors who were “unwilling” to unilaterally disarm. The A2D strategy thus created an illegal arms market in the Cluster.

Finally, C2D’s use of a common regional border (commonly known as, the “One-Stop Border, OSBPs”), crossings for managing cross-border communities has been less effective in preventing the proliferation of SALW. The OSBP is part of the connective infrastructure that links communities and services across borders.60Note: Paul Nuget and Isabella Soi, “One-stop border posts’ in East Africa: State encounters of the fourth kind,” Journal of Eastern Africa Studies 14, no. 3 (2020): 433-454. Recent studies on the effectiveness of the OSBPs has shown that one of the limiting factors of the facility is institutional rivalries between agencies managing the various aspects of the border.61Note: Ibid, p. 448. This struggle usurps the synergies that would otherwise be harnessed for monitoring and responding to the proliferation of SALW and other transnational criminal activities. No wonder, its application on the Kenya-Ethiopia border has not worked due to varying institutional arrangement and pattern in both countries. To date, allowing pastoral mobility has been seen as a way to promote inter-community trust needed for controlling illegal goods and arms smuggling in the Cluster. However, the ownership of weapons between Kenyan and Ethiopian communities varied considerably. In most cases, the Kenyan border communities were rendered vulnerable as the neighboring Ethiopian Oromo remained heavily armed. In this case, naturally, disarmament could only succeed if there was an effective partnership between the Kenyan and Ethiopian Oromos.62Note: William Gifford, “Strengthening Regional Security: Helping Kenya Destroy Excess Small Arms and Light Weapons Stockpiles,” United States Department of State (blog), October 29, 2021, https://www.state.gov/dipnote-u-s-department-of-state-official-blog/strengthening-regional-security-helping-kenya-destroy-excess-small-arms-and-light-weapons-stockpiles/.

Alternatives to the C2D Model

Given the limitations of C2D, community leaders from the Karamoja Cluster offered their preferred approach to disarmament and preventing atrocities. Their suggestion included two aspects. First, the need for social protection initiatives is vital given the number of cash-poor members of the Cluster who make ends meet through diverse localized family support systems. Secondly, to apply this social protection thinking to disarmament, the delegates advocated what they characterized as “a social connectivism.” Social connectivism is a social world constructed by agents through what I call “human-to-human bonding” (H2HB).

In this regard, an H2HB approach to disarmament is a preferred process that creates social identity, belonging, survival, sharing, and forming solidarity clubs among the pastoral communities. However, this proposed human relational approach is likely to fail because of increasing levels of state fragility. Therefore, efforts to integrate H2HB thinking into the disarmament program must be anchored in social institutions and a belief system of the pastoral communities as part of policy refinement articulated in the following section.

Recommendations for an Alternative Approach to Disarmament

This paper builds on Travis Hirschi’s63Note: Travis Hirschi, Causes of Delinquency, 1969, https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781315081649. idea of social bonding, or social connectivism, to explore alternative approaches to tackling the problem of SALW proliferation and preventing atrocities. Hirschi’s idea of social bonding is premised on four elements: attachment, commitment, involvement, and belief.64Note: Travis Hirschi and Michael R. Gottfredson, “In Defense of Self-Control,” Theoretical Criminology 4, no. 1 (February 2000): 55–69, https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480600004001003. The primacy of kinship as a bridge that connects individuals or groups is anchored on principles of egalitarianism: promoting communal living, a sense of social identity, and belonging, all of which strengthen people’s ability to bond to survive. In other words, social relationships support the society in sharing information on important aspects of day-to-day life, such as, access to livelihoods assets, warnings on security threats as well as strengthening the ties across structures of the pastoral community. Indeed, social network theorists have identified social structures upon which evolution of bahaviour occurs, including; knowledge structures and processes, interaction among individuals, and the emergence of structured relations that is responsible for building trust across cultures.65Note: Jens Krause, Darren P. Croft and Richard James, “Social network theory in the behavioural sciences: potential applications,” Behavioural Ecology and Sociobiology 62, no. 1 (2007): 15-27. Similarly, in the Karamoja Cluster, despite significant security threats the Karamojans face, including organized gangsterism, armed militias and irregular migration, the community has built up complex social structures from the Kinship interaction through which they are able to share livestock resources (water and grazing land), as well as collectively diffuse risks associated with the said challenges.

Therefore, social connection fits into the goal of transforming disarmament into a human security phenomenon anchored in the justice system. However, the pertinent question remains: How do you serve justice to victims of atrocities in the absence of a codified crime? How do structures and processes lead to interactive relations? What drives the formation of patterned behavior? How does behavior sustain transactions and exchanges over time? Bonding is the glue that coheres all these processes and behavioral patterns together through attachment and belief systems.

Integrate Social Attachment and Kinship Structures in the Regional Disarmament Policy

When asked about the future of disarmament in the Karamoja Cluster, most respondents attending the 2021 Entebbe Leaders Conference emphasized the individual’s attachment to various social institutions, family, and peers across borders. As an alternative to state-driven C2D, the Clusters’ community leadership indicated their preference to sustain individuals’ connection with family members and that individuals belonging to such strong networks were less likely to commit a crime or get involved in deviant behaviors. One of the experts facilitating the Entebbe Leaders Conference noted:

“The social bond builds commitment, aspirations, actualization of life goals such as education, marriage etc. I would like to emphasize that emotional closeness to family, peers, and value systems flourish in individuals that are closely integrated”.

Interview with Prof. Alfred Lokuji Sebit, March 24, 2021

In this regard, the H2HB approach is particularly significant as it has been found to promote individuals’ integration intosociety and that individual’s movement toward one’s goal becomes mutually beneficial to others’ goals. Although C2D is explicit about procedures for disarming the communities, this has not eliminated the problems of cyclic armament through informal networks across borders. These networks, driven by kinship, have worsened the proliferation of illicit SALW and violence in the Karamoja Cluster. This inconsistency raises the question of reliability in using C2D to prevent atrocities in transnational conflict scenarios. Given the kinship that often accompanies fictive kinship in the Horn of Africa and among the Karamoja ethnic groups, the possibility of using the human-human bond (H2HB) approach to managing the proliferation of SALW arises.

Specific policy recommendations for RECSA and other international stakeholders include:

- The strategy for conducting disarmament must be comprehensive to recognize the role of social and kinship connections across borders and to include initiatives such as a social development agenda and infrastructure connections to increase “borderless” access to basic facilities such as schools and health facilities, and other social support mechanisms.

- Behavioral change strategies should be incorporated into broader illegal arms control programming, including a “mindset” transformation on cattle raiding and lifestyle.

- The RECSA cooperating member states should empower the local administration to protect and preserve mobility corridors for pastoralists and herds.

- There is a need to invent simple surveillance technologies to curb illicit activities such as arms trafficking and human trafficking. However, it is essential to note that for such technologies to function effectively, security in its broadest perspective — good governance, social co-existence, and ethical crowdsourcing of information through social media — must undergird constructive uses of technology.66Note: Francis Onditi and Robert Gateru, “Technologizing Infrastructure for Peace in the Context of Fourth Industrial Revolution,” in The Disruptive Fourth Industrial Revolution, ed. Wesley Doorsamy, Babu Sena Paul, and Tshilidzi Marwala, vol. 674, Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020), 47–68, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48230-5_3. Human security is a precursor to the effective surveillance, management, and monitoring of human beings and livestock movements.

- Deliberate efforts should be undertaken to incorporate local philosophies such as “brothers’ keepers” as a function of social bonding in the disarmament strategies and plans.

The Disarmament Strategies Should Recognize the Importance of Pastoral Communities’ Social Value System

Both policy and scholarly discourses have divided views on the role of belief systems in conducting disarmament. Nevertheless, there is a natural human tendency to believe in societal values. The reverse is also true: The propensity to believe depends upon an individual’s attachment to the society to which they belong. Studies on micro-disarmament have shown how a pastoral community member who cares about what other group members think of them is likely to guard against armed raiding or violence.67Note: Christopher D. Carr, “The Security Implications of Microdisarmament,” Counterproliferation Paper, Future Warfare Series (Air War College: USAF Counterproliferation Center, January 2000), https://media.defense.gov/2019/Apr/11/2002115470/-1/-1/0/05SECURITY.PDF. A lack of recognition of shared values across borders could reinforce harmful competition, leading to aggressive and obstructive behaviors. Although the Karamoja communities are organized based on a tribal belief system, this can reinforce aggression and armed violence. Notably, the role of social bonding in violent extremism introduces ideology as a critical driver to cyclic armament. Therefore, specific recommendations for RECSA and other international stakeholders include:

- Civil-military relations should be factored into the disarmament processes as there is a need to strengthen collaboration between local officials, the military, and other stakeholders.

- The family-based learning (FBL) approach considers learning a social activity. The FBL approach would be an ideal alternative for children in the Karamoja Cluster, who spend the early part of their lives tending livestock with guns.

- Encourage the use of the “guns for money” slogan as a part of the human relational disarmament framework. The framework should be anchored on the four key pillars of social connection (attachment, commitment, involvement, and belief).

Conclusion

The contemporary world order is one in which wars and conflicts are no longer the sole preserve of the state and where informalities dominate. Thus, interventions for sustainable peace and stability must empower human relations and social bonding. For the communities of the Karamoja Cluster, social bonding remains the single most important mechanism for addressing the problem of the proliferation of small arms and light weapons. However, any alternative approach requires the international community to adopt models that complement the local order and realities to achieve balanced disarmament among cross-border communities. This is hard to achieve, especially when border communities and local authorities continue to improvise their own forms of disarmament, both punitive and rewarding. As the fighting continues in the Cluster, the C2D experience can provide a lesson on the limitations of state-centric approaches in resolving cross-border conflicts that are deeply embedded in human relations.

Acknowledgments

This paper is part of the ongoing research into understanding ‘closeness centrality’ in social networks, using the intertribal border markets as the basis for experimenting human relations as “factories” of conflict and infrastructure for peace (I4P). These studies, are being conducted under the Francis Onditi Conflictology lab, with the aim of engaging local solutions and models to address the challenges faced by fragile states68Note: Natalie Fiertz et al., “Fragile States Index 2021,” Annual Report (Washington, DC: Fund for Peace, May 20, 2021), https://fragilestatesindex.org/2021/05/20/fragile-states-index-2021-annual-report/. and pastoral communities in the Horn of Africa. I would like to sincerely thank members of my lab, including those who virtually contributed or attended the Methodological Workshop at Riara University on June 7, 2022; Shadrack Kithiia, Constansia Mumma-Martinon, Holly Ritchie, Philip Omondi, Linda Ogallo, Redempter Mutinda, Anthony Gitonga, Manuel Mutio, Peter Mecha and Matilda Owino, for their thoughtfulness and criticisms. Nelson Wanyonyi and James Yuko were research assistants to the project. Finally, I thank Ilhan Dahir, Jim Finkel, Shakiba Mashayekhi, and Lisa Sharland from the Stimson Center for their editorial feedback.

About the Author

Francis Onditi is an associate professor of conflictology and dean of the School of International Relations and Diplomacy, Riara University, Kenya. He was recently ranked among the World’s Top 2% scientists of the year 2022 listed by the Stanford University, USA. Francis is the Principal Investigator (PI) in the Francis Onditi Conflictology lab, focused on studying how conflict evolves in group dynamics and network formations, using ‘closeness centrality’ measure, in the inter-tribal border market spaces. His epistemic research affiliation is conflictology, specializing in the geography of conflict, institutional evolution theory, social network theory, regional integration, and civil-military relations. Francis’s main contribution to knowledge is modeling, thinking of uncharted models, and developing theoretical frameworks and concepts to explain occurrence and prevalence of conflict in time and space.

Photo header credit: Francis Onditi Conflictology Lab.

Notes

- 1Note: This study adopts David Ronfeldt’s (1996) definition of kinship to mean, attachment, commitment, involvement and belief system anchored on principles of egalitarianism- promoting communal living, sense of social identity and belonging, hence strengthening people’s ability to integrate and co-exist. Further reference can be made to: David Ronfeldt, Tribes, Institutions, Markets, Networks: A Framework about Societal Evolution (Santa Monica: RAND 1996).

- 2Note: Milas Siefulaziz and Group, “Baseline Study for the Ethiopian Side of the Karamoja Cluster,” https://www.cewarn.org/index.php/reports/archived-early-warning-reports/baseline-reports/eth-2/60-bsline-krj-eth/file. Thirteen ethnic groups sharing similar linguistic and socio-cultural ties occupy the Cluster. Note: Andy Catley, Elizabeth Stites, Mesfin Ayele and Raphael L. Arasio, “Introducing Pathways to Resilience in the Karamoja Cluster,” doi: 10.1186/s13570-021-00214-4

- 3Note: “The Nairobi Protocol for the Prevention, Control and Reduction of Small Arms and Light Weapons in the Great Lakes Region and the Horn of Africa,” n.d., https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/research/disarmament/dualuse/pdf-archive-att/pdfs/recsa-nairobi-protocol-for-the-prevention-control-and-reduction-of-small-arms-and-light-weapons-in-the-great-lakes-region-and-the-horn-of-africa.pdf.

- 4Note: “Nairobi Declaration,” n.d., https://archive.globalpolicy.org/security/smallarms/regional/nairobi.htm.

- 5Note: The Nairobi Protocol on the Prevention, Control, and Reduction of Small Arms and Light Weapons in the Great Lakes Region, the Horn of Africa, and Bordering States. For more details on the assessment of the status of the protocol, consult, Simone Wisotzki, “Efforts to curb the proliferation of small arms and light weapons: from persistent crisis to norm failure?” Z Friedens und Konflforsch 10 (2021): 247-271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42597-022-00073-9.

- 6Note: Regional Centre on Small Arms, Guidelines for establishment and functioning of National Institutions Responsible for SALW Management and Control. Available at: https://recsasec.org/index.php/page/view?id=MzE=.

- 7Note: “SDG Indicators,” UN Sustainable Development Goals, n.d., https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/metadata/?Text=&Goal=&Target=16.4.

- 8Note: United Nations, Goal 16: Promote justice, peaceful and inclusive societies. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/peace-justice/.

- 9Note: “The Nairobi Protocol for the Prevention, Control and Reduction of Small Arms and Light Weapons in the Great Lakes Region and the Horn of Africa.”

- 10Note: Dominique Dye, “Arms Control in a Rough Neighbourhood: The Case of the Great Lakes Region and the Horn of Africa,” Institute for Security Studies Papers 2009, no. 179 (2009): 179, https://issafrica.org/research/papers/arms-control-in-a-rough-neighbourhood-the-case-of-the-great-lakes-region-and-the-horn-of-africa.

- 11Note: The RECSA Cooperating states include Republic of Burundi, Central African Republic, Republic of Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, Republic of Djibouti, Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, State of Eritrea, Republic of Kenya, Republic of Rwanda, Republic of Seychelles, Federal Republic of Somalia, Republic of South Sudan, Republic of the Sudan, United Republic of Tanzania, Republic of Uganda.

- 12Note: Elizabeth Stites and Darlington Akabwai, “‘We Are Now Reduced to Women’: Impacts of Forced Disarmament in Karamoja, Uganda,” Nomadic Peoples 14, no. 2 (2010): 24–43, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43123871.

- 13Note: Patrick Kachope, “Micro-Disarmament Experiences in Africa: Learning from the Karamoja Integrated Disarmament and Development Programme, Northeastern Uganda,” African Security Review 30, no. 3 (July 3, 2021): 271–89, https://doi.org/10.1080/10246029.2020.1828117.

- 14Note: In this study, human relation is anchored on five pillars: local value system, kinship, social bonding, culture and norms.

- 15Note: Milas Siefulaziz and InterAfrica Group, “Baseline Study for the Ethiopian Side of the Karamoja Cluster” (Inter Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD) Region, 2004), https://www.cewarn.org/index.php/reports/archived-early-warning-reports/baseline/eth-2/60-bsline-krj-eth/file.

- 16Note: Francis Onditi, “Quasi-experimental studies of tribal markets as factories of conflict and infrastructures for peace (I4P) in Kenya (production, distribution, consumption & transformation of conflict). Unpublished Research Proposal Licensed by the National Commission for Science, Technology & Innovation (NACOSTI), License No: NACOSTI/P/22/16916. April 2022.

- 17Note: The Karamoja Cluster ethnic groups include; the Bokora, Dessenech, Didinga, Dodoth, Jie, Matheniko, Nyangatom, Thur, Pian, Pokot, Tepeth, Topotha and Turkana. Andy Catley et al., “Introducing Pathways to Resilience in the Karamoja Cluster,” Pastoralism 11, no. 1 (November 24, 2021): 28, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13570-021-00214-4.

- 18Note: IGAD, “Baseline Study for the Ethiopian Side of the Karamoja Cluster”, 2004. Available at: https://www.cewarn.org/index.php/reports/archived-early-warning-reports/baseline-reports/eth-2/60-bsline-krj-eth/file.

- 19Note: “Regional Report on the Nexus Between Illicit SALW Proliferation and Cattle Rustling Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan and Uganda,” 2016. Available at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/REGIONAL-REPORT-ON-THE-NEXUS-BETWEEN-ILLICIT-SALW/8975c0308b66fd5aba494f7b78d47cd5100fae21.

- 20Note: Stites and Akabwai, “‘We Are Now Reduced to Women’: Impacts of Forced Disarmament in Karamoja, Uganda.” Nomadic Peoples 14, no. 2 (2010): 24-43.

- 21Note: Thus, this category includes the Merille of Ethiopia, the Pokot of Kenya and Didinga of South Sudan; The Karamojong are further sub-divided into; the Pian, the Upe, the Bokora, the Tepes, the Matheniko, the Jie and the Dodoth. “Karamojong Cluster Harmonisation Meeting” (Karamojong Cluster Harmonisation Meeting, Lodwar, Kenya: Organization of African Unity Interafrican Bureau for Animal Resources, 1999), https://fic.tufts.edu/wp-content/uploads/AU-IBAR-Lodwar-Meeting.pdf.

- 22Note: Siân Herbert and Izzy Birch, “Cross-Border Pastoral Mobility and Cross-Border Conflict in Africa: Patterns and Policy Responses,” Evidence Synthesis (International Development Department, College of Social Sciences: GSDRC, January 2022), https://gsdrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/2021-12-09_GSDRC-Pastoralist-Mobility-FINAL2-1.pdf.

- 23Note: The everyday life of the communities occupying the Karamoja Cluster defines how and where they draw water, where they take their livestock for grazing, how they socialize and how safe they felt in their own homesteads.

- 24Note: Andy Catley, Elizabeth Stites, Mesfin Ayele and Raphael L. Arasio, ‘Introducing pathways to resilience in the Karamoja Cluster. Pastoralism: Research, Policy and Practice (2021).

- 25Note: Kennedy Mkutu, “Pastoral Conflict and Small Arms: The Kenya-Uganda Border Region” (International Development Department, College of Social Sciences: GSDRC, 2003), https://www.saferworld.org.uk/downloads/pubdocs/Pastoral%20conflict.pdf.

- 26Note: Xue Han et al., “Attribution of the Extreme Drought in the Horn of Africa during Short-Rains of 2016 and Long-Rains of 2017,” Water 14, no. 3 (2022), https://doi.org/10.3390/w14030409. This has kept the Karamoja cluster and its estimated population of 1.4 million Note: “Resilience Analysis of Karamoja (Uganda)” (Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, January 15, 2018), https://www.fao.org/3/i8365en/I8365EN.pdf.

- 27Note: The four IGAD member states located in the Karamoja Cluster include Ethiopia, Kenya, South Sudan, and Uganda. More information on the geography and culture of the Karamoja Cluster can be found here: https://resilience.igad.int/clusters/igad-cluster-1-karamoja-cluster/

- 28Note: “Livestock and Poverty in Karamoja: An Analysis of Livestock Ownership, Thresholds, and Policy Implications” (Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, January 31, 2019), https://www.fao.org/in-action/kore/publications/publications-details/en/c/1178860/.

- 29Note: Regional Centre on Small Arms, A Report of Analysis on Armed Crimes in East Africa Community Countries (Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda). (Regional Centre on Small Arms, 2016), https://books.google.com/books?id=vuEcxwEACAAJ.

- 30Note: “Report of the IGAD Regional Workshop on the Disarmament of Pastoralist Communities” (Entebbe: Conflict Early Warning and Response Mechanism (CEWARN), May 28, 2007), https://www.cewarn.org/index.php/reports/special-reports/2-igad-regional-workshop-on-the-disarmament-of-pastoralist-communities/file.

- 31Note: Janpeter Schilling, Francis Opiyo and Jurgen Scheffran, “Raiding pastoral livelihoods: Motives and effects of violent conflict in North-Western,” Pastoralism 2, no. 25 (2012): 1-16: Also see, Mark O’Keefe, “Chronic crises in the Arc of insecurity: a case study of Karamoja,” Third World Quarterly 31, no. 8 (2010): 1271-1295.

- 32Note: Ungoverned space is the physical or non-physical area where there is absence of state capacity or political will to exercise control. Angel Rabasa et al., Ungoverned Territories: Understanding and Reducing Terrorism Risks, 1st ed. (RAND Corporation, 2007), https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7249/mg561af.

- 33Note: “Presentation at RECSA Cross Border Leaders Conference on Resources Management, Conflict Management and SALW Proliferation Control” (RECSA Cross Border Leaders Conference on Resources Management, Conflict Management and SALW Proliferation Control, Entebbe, March 24, 2021), https://www.att-assistance.org/activity/recsa-cross-border-leaders-conference-resources-management-conflict-management-and-salw.

- 34Note: Fund for Peace, Measuring fragility: Risk and vulnerability in 179 countries. Washington D.C. https://fragilestatesindex.org/.

- 35Note: Dave Eaton, “The rise of traider: the commercialization of raiding in Karamoja,” Nomadic Peoples 14, no.2 (2010): 106-122.

- 36Note: LIam Taylor, “In Uganda’s Karamoja, Rampant Rustling and a Militarised Response as Violence Returns,” The New Humanitarian, January 26, 2022, https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news-feature/2022/1/26/Uganda-Karamoja-cattle-rustling-militarised-violence-returns.

- 37Note: Ochieng Adala, “Nonproliferation in Eastern Africa,” Southern Flows: (Stimson Center, 2014), JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep11012.7.

- 38Note: Padmini Iyer, “Friendship, Kinship and Social Risk Management Strategies among Pastoralists in Karamoja, Uganda,” Pastoralism 11, no. 1 (December 2021): 24, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13570-020-00182-1.

- 39Note: David Ronfeldt, Tribes, Institutions, Markets, Networks: A Framework about Societal Evolution (Santa Monica: RAND 1996).

- 40Note: Pamela Machakanja and Chupicai Shollah Manuel, “Southern Africa: Regional Dynamics of Conflict and the Proliferation of Small Arms and Light Weapons,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Small Arms and Conflicts in Africa (Springer, 2021), 983–1001

- 41Note: Laura Freeman, “Environmental Change, Migration, and Conflict in Africa: A Critical Examination of the Interconnections,” The Journal of Environment & Development 26, no. 4 (2017): 351–74.

- 42Note: Philip Stibbe, Challenges to disarmament, demobilization and reintegration. E- International Relations, September 2012. Available at: https://www.e-ir.info/2012/09/02/challenges-to-disarmament-demobilisation-and-reintegration/#_ftnref8.

- 43Note: Kabiito Bendicto, “Culture, Resources and the Gun in the Violent-Conflict Expression.” Available at: https://ir.umu.ac.ug/handle/20.500.12280/2860.

- 44Note: James E. Burroughs and Eric Rindfleisch, “Materialistic and Well-being: A Conflict Values Perspective.” Journal of Consumer Research 29, no. 3 (2002), 348-370.

- 45Note: Johan Galtung, “Violence, Peace, and Peace Research,” Journal of Peace Research 6, no. 3 (1969): 167–91.

- 46Note: The five factors driving vulnerability in the Karamoja Cluster include environmental change and economic inequalities, cyclic armament, circular migratory behavior, and gun violence.

- 47Note: Liam Taylor, “In Uganda’s Karamoja, Rampant Rustling and a Militarised Response as Violence Returns.”

- 48Note: Elizabeth Stites, “Gender in Light of Livelihood Trends in the Karamoja Cluster” (KRSU Conference, Moroto, Uganda, 2019), https://karamojaresilience.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/14ec3c_090702f8afd44da8b1d695441ee92335.pdf.

- 49Note: Francis Onditi and Josephine Odera, Understanding Violence against Women in Africa: An Interdisciplinary Approach (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021).

- 50Note: Raphael Lotira Arasio, Andy Catley, and Mesfin Ayele, “Rapid Assessment of COVID-19 Impacts in Karamoja, Uganda,” Technical Report for the Karamoja Development Partners Group (Uganda: Kampala Resilience Support Unit-USAID/Uganda, August 2020), https://karamojaresilience.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/tufts_2037_krsu_covid_19_v2_online-2.pdf.

- 51Note: Randy Rydell, “The Guterres Disarmament Agenda and the Challenge of Constructing a Global Regime for Weapons,” Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament 3, no. 1 (January 2, 2020): 21–40, https://doi.org/10.1080/25751654.2020.1764259.