By Rachel Stohl and Elizabeth Peartree:

Today, the State Department released its annual list of countries that are known to use or support the use of child soldiers. What is most notable this year is not who is included on the list, but rather who is omitted. Afghanistan is noticeably absent from the list despite having been previously identified by both the United States and the United Nations for using child soldiers in its government-supported armed groups. With this omission, the State Department has unfortunately missed an opportunity to use the power of U.S. law to encourage Afghanistan to stop using child soldiers.

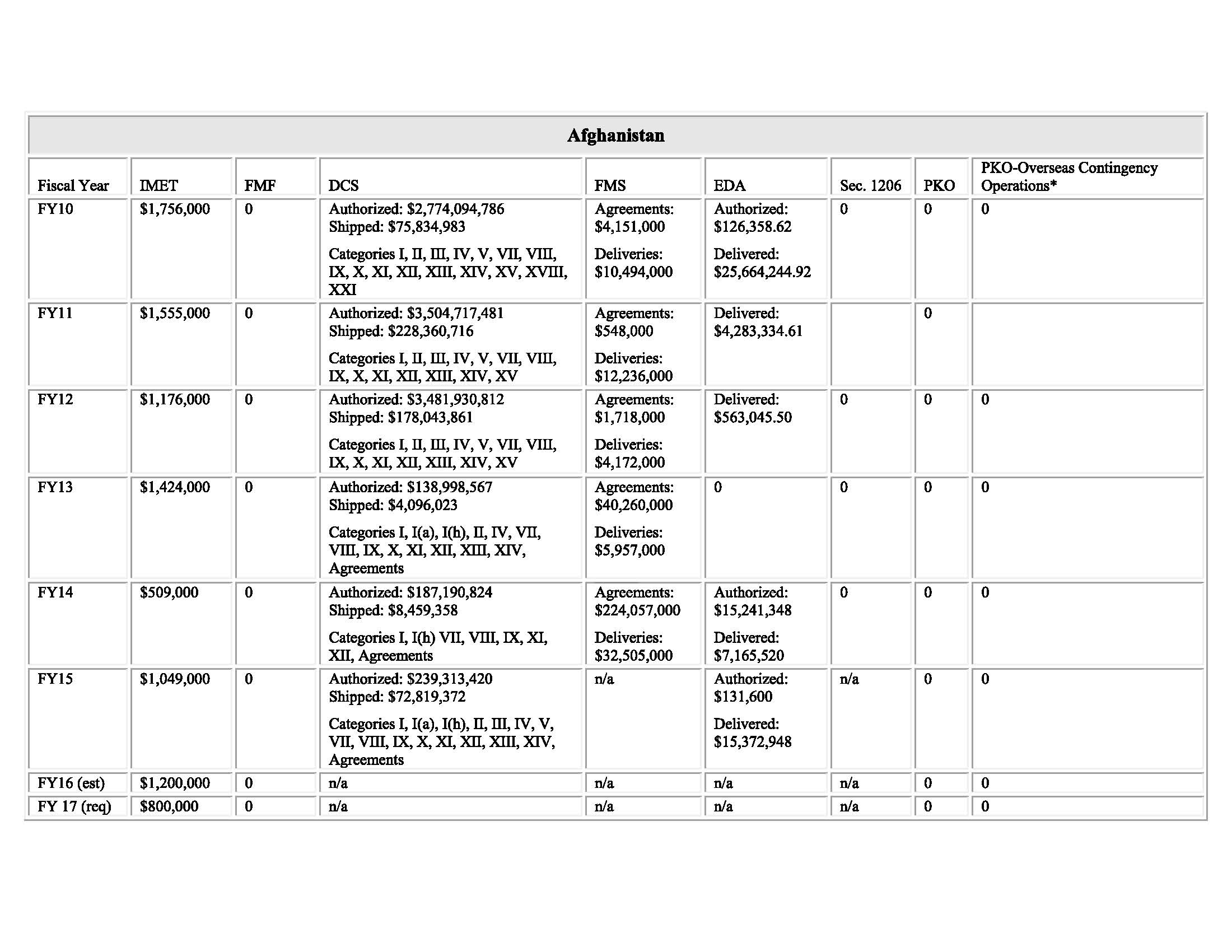

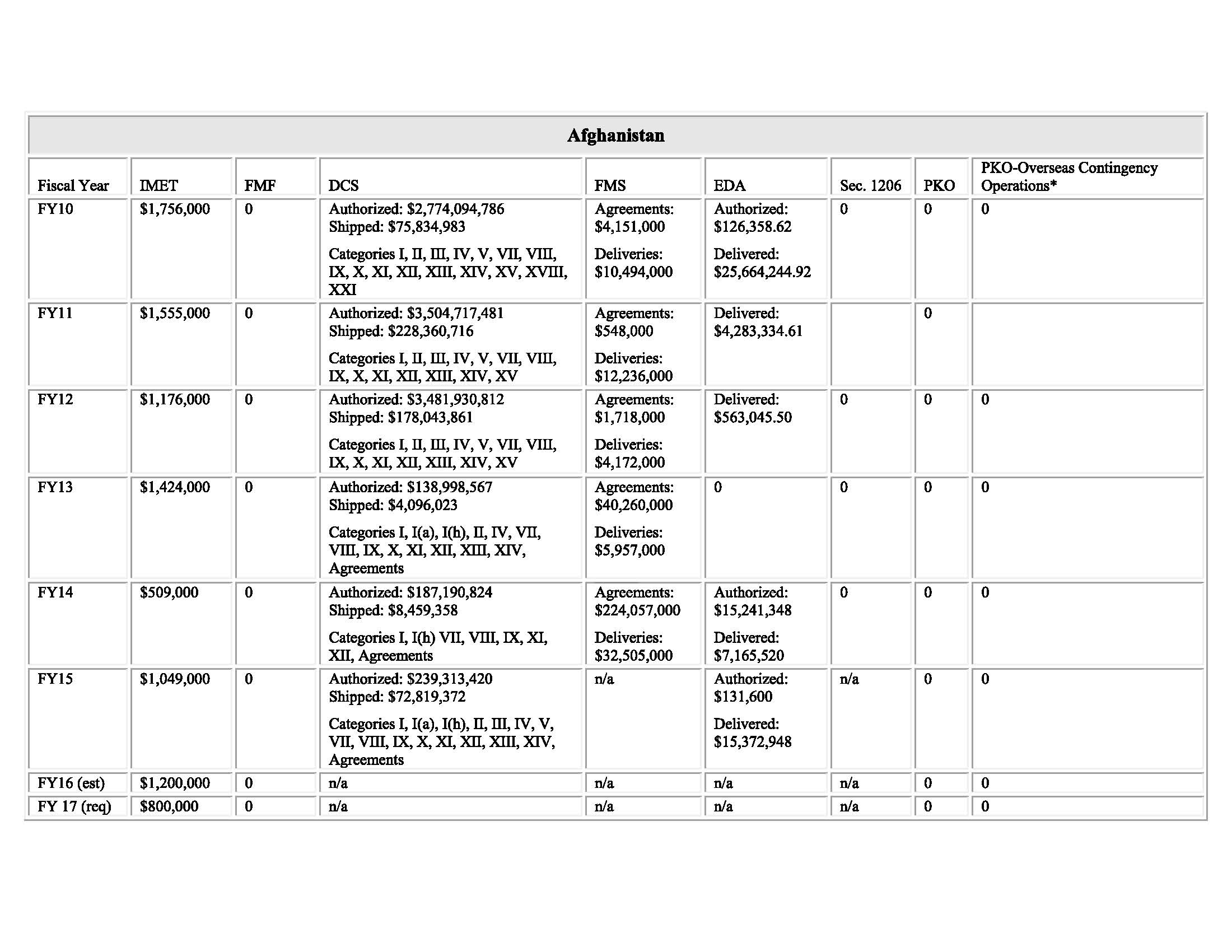

The Child Soldiers Prevention Act (CSPA), passed by Congress in 2008 and which went into effect in 2010, requires the State Department to annually identify states that have “governmental armed forces or government-supported armed groups that recruit and use child soldiers.” These countries are listed in the Trafficking in Persons (TIP) report and subsequently prohibited from receiving certain categories of arms transfers and military assistance. The law only applies to eight categories of military aid that fall under both State and Defense Department accounts – International Military Education and Training (IMET), Foreign Military Financing (FMF), Direct Commercial Sales (DCS), Foreign Military Sales (FMS), Excess Defense Articles, Section 1206, Peacekeeping Operations, and Peacekeeping Operations provided through the Overseas Contingency Operations fund. The law, however, allows the president to waive these prohibitions — in part or in full — for any given country under specific circumstances. Those countries that receive full or partial waivers are then permitted to receive U.S. military assistance that would otherwise be withheld.

The 2016 TIP report identified 10 governments that use child soldiers in their own militaries or in government-supported groups: Burma, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iraq, Nigeria, Rwanda, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen. Of note this year is the inclusion of Iraq for the first time and the return of Rwanda to the list. All other countries are repeat offenders, having been included on the CSPA list before. In fact, DRC, Somalia, South Sudan (for every year since its independence), Sudan, and Yemen have appeared on the CSPA list since its 2010 inception. The 10 countries combined are potentially slated to receive at least $303 million in CSPA sanctionable military assistance alone in Fiscal Year 2017.

The omission of Afghanistan, however, is disappointing. Indeed, the use of child soldiers in Afghanistan spans across more than a decade of war in the country, in which both the United States and the United Nations have documented the use of child soldiers in the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces, including the Afghan National Police, the Afghan Local Police, and the Afghan National Army. For example, the State Department’s 2015 human rights practices country report for Afghanistan reported that ANDSF and pro-government militias recruited and used children for military purposes. Although the Human Rights reports are not the only source of information for the TIP report — which is compiled separately — the United States government has a track record of recognizing the Afghan government as having recruited and used child soldiers. Additionally, the United Nation’s annual children in armed conflict report revealed that “thirteen verified recruitment cases were attributed to the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces: five to the Afghan Local Police; five to the Afghan National Police; and three to the Afghan National Army” this year alone.

The 2016 TIP report, while acknowledging credible evidence of child soldier recruitment by the ALP in 2015 and 2016, does not list Afghanistan on the CSPA list and claims that, “Although the ALP is a government security force in Afghanistan, it falls outside of the armed forces of the country as defined by the CSPA.”

But this distinction is nebulous at best. Police forces in Afghanistan fill more than traditional police roles. Indeed, they are central players in counter-terrorism operations and often take direct part in combat, conducting security operations akin to military operations and sometimes fighting alongside regular armies. They often face similar, if not identical, experiences as that of the Afghan military, including risks of attack by enemy forces.

Further, the CSPA covers governmental armed forces and government-supported armed groups — including paramilitaries, militias, or civil defense forces – that recruit and use child soldiers. The term “including” is not limited to the groups described in the act. Thus, given that the activities of the Afghan National Police/Afghan Local Police are similar to those undertaken by the Afghan military, it is wholly appropriate for the Afghan Local Police to be covered by the CSPA.

The omission of Afghanistan has more to do with national security than human rights. Since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Afghanistan has been a national security priority for the United States. As the United States seeks to support the Afghan government and its capabilities to fight insurgent groups such as al-Qaeda and the Taliban, the administration has repeatedly placed its security interests over the plight of the most vulnerable.

In the past five years, the United States government has provided Afghanistan with nearly $8 billion in arms sales and more than $34 billion in military assistance across the eight categories detailed above. This is in addition to billions of dollars in assistance for counterterrorism, stability, and security efforts not that are not affected by the CSPA prohibitions. This defense relationship is strong and policymakers are unwilling to put it at risk.

But, Afghanistan’s presence on the TIP list doesn’t necessarily compel the United States to stop providing military assistance. Through the waiver process, the president could waive some or all of the prohibitions required by law. Placing Afghanistan on the list, however, would allow the U.S. to engage in dialogue and put the Afghan government on notice. A similar approach has been taken with Yemen. Although Yemen has been on the CSPA list every year since 2010, the U.S. has provided more than $230 million in military assistance and over $63 million in arms transfers since the law came into effect, withholding assistance and arms only in the last year due to political turmoil and conflict within Yemen, separate from CSPA provisions.

The release of this year’s CSPA list represents a missed opportunity to influence Afghanistan to make more of an effort against the practice of recruiting and using child soldiers. The CSPA is intended to leverage the provision of U.S. military assistance to encourage governments to stop using child soldiers or supporting those that do. Unfortunately, the Afghan government has received an unwarranted pass in this regard and will be allowed to continue to use child soldiers with no incentive to alter its behavior.

___

Rachel Stohl is the director of the Conventional Defense program at the Stimson Center. Elizabeth Peartree is an intern for the Conventional Defense program.

Afghanistan Missing from Obama Administration’s Annual Child Soldiers List

By Rachel Stohl

In Conventional Arms

By Rachel Stohl and Elizabeth Peartree:

Today, the State Department released its annual list of countries that are known to use or support the use of child soldiers. What is most notable this year is not who is included on the list, but rather who is omitted. Afghanistan is noticeably absent from the list despite having been previously identified by both the United States and the United Nations for using child soldiers in its government-supported armed groups. With this omission, the State Department has unfortunately missed an opportunity to use the power of U.S. law to encourage Afghanistan to stop using child soldiers.

The Child Soldiers Prevention Act (CSPA), passed by Congress in 2008 and which went into effect in 2010, requires the State Department to annually identify states that have “governmental armed forces or government-supported armed groups that recruit and use child soldiers.” These countries are listed in the Trafficking in Persons (TIP) report and subsequently prohibited from receiving certain categories of arms transfers and military assistance. The law only applies to eight categories of military aid that fall under both State and Defense Department accounts – International Military Education and Training (IMET), Foreign Military Financing (FMF), Direct Commercial Sales (DCS), Foreign Military Sales (FMS), Excess Defense Articles, Section 1206, Peacekeeping Operations, and Peacekeeping Operations provided through the Overseas Contingency Operations fund. The law, however, allows the president to waive these prohibitions — in part or in full — for any given country under specific circumstances. Those countries that receive full or partial waivers are then permitted to receive U.S. military assistance that would otherwise be withheld.

The 2016 TIP report identified 10 governments that use child soldiers in their own militaries or in government-supported groups: Burma, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iraq, Nigeria, Rwanda, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen. Of note this year is the inclusion of Iraq for the first time and the return of Rwanda to the list. All other countries are repeat offenders, having been included on the CSPA list before. In fact, DRC, Somalia, South Sudan (for every year since its independence), Sudan, and Yemen have appeared on the CSPA list since its 2010 inception. The 10 countries combined are potentially slated to receive at least $303 million in CSPA sanctionable military assistance alone in Fiscal Year 2017.

The omission of Afghanistan, however, is disappointing. Indeed, the use of child soldiers in Afghanistan spans across more than a decade of war in the country, in which both the United States and the United Nations have documented the use of child soldiers in the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces, including the Afghan National Police, the Afghan Local Police, and the Afghan National Army. For example, the State Department’s 2015 human rights practices country report for Afghanistan reported that ANDSF and pro-government militias recruited and used children for military purposes. Although the Human Rights reports are not the only source of information for the TIP report — which is compiled separately — the United States government has a track record of recognizing the Afghan government as having recruited and used child soldiers. Additionally, the United Nation’s annual children in armed conflict report revealed that “thirteen verified recruitment cases were attributed to the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces: five to the Afghan Local Police; five to the Afghan National Police; and three to the Afghan National Army” this year alone.

The 2016 TIP report, while acknowledging credible evidence of child soldier recruitment by the ALP in 2015 and 2016, does not list Afghanistan on the CSPA list and claims that, “Although the ALP is a government security force in Afghanistan, it falls outside of the armed forces of the country as defined by the CSPA.”

But this distinction is nebulous at best. Police forces in Afghanistan fill more than traditional police roles. Indeed, they are central players in counter-terrorism operations and often take direct part in combat, conducting security operations akin to military operations and sometimes fighting alongside regular armies. They often face similar, if not identical, experiences as that of the Afghan military, including risks of attack by enemy forces.

Further, the CSPA covers governmental armed forces and government-supported armed groups — including paramilitaries, militias, or civil defense forces – that recruit and use child soldiers. The term “including” is not limited to the groups described in the act. Thus, given that the activities of the Afghan National Police/Afghan Local Police are similar to those undertaken by the Afghan military, it is wholly appropriate for the Afghan Local Police to be covered by the CSPA.

The omission of Afghanistan has more to do with national security than human rights. Since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Afghanistan has been a national security priority for the United States. As the United States seeks to support the Afghan government and its capabilities to fight insurgent groups such as al-Qaeda and the Taliban, the administration has repeatedly placed its security interests over the plight of the most vulnerable.

In the past five years, the United States government has provided Afghanistan with nearly $8 billion in arms sales and more than $34 billion in military assistance across the eight categories detailed above. This is in addition to billions of dollars in assistance for counterterrorism, stability, and security efforts not that are not affected by the CSPA prohibitions. This defense relationship is strong and policymakers are unwilling to put it at risk.

But, Afghanistan’s presence on the TIP list doesn’t necessarily compel the United States to stop providing military assistance. Through the waiver process, the president could waive some or all of the prohibitions required by law. Placing Afghanistan on the list, however, would allow the U.S. to engage in dialogue and put the Afghan government on notice. A similar approach has been taken with Yemen. Although Yemen has been on the CSPA list every year since 2010, the U.S. has provided more than $230 million in military assistance and over $63 million in arms transfers since the law came into effect, withholding assistance and arms only in the last year due to political turmoil and conflict within Yemen, separate from CSPA provisions.

The release of this year’s CSPA list represents a missed opportunity to influence Afghanistan to make more of an effort against the practice of recruiting and using child soldiers. The CSPA is intended to leverage the provision of U.S. military assistance to encourage governments to stop using child soldiers or supporting those that do. Unfortunately, the Afghan government has received an unwarranted pass in this regard and will be allowed to continue to use child soldiers with no incentive to alter its behavior.

___

Rachel Stohl is the director of the Conventional Defense program at the Stimson Center. Elizabeth Peartree is an intern for the Conventional Defense program.

Photo credit: ResoluteSupportMedia via Flickr