Introduction

This report details the proceedings and findings of the October 2021 Protection of Civilians Tabletop Exercise (TTX), which was organised by PAX and the Stimson Center, held at the First Germany Netherlands Corps (1 GNC) Headquarters, and jointly developed and facilitated by the Cordillera Applications Group (CAG). This innovative, first-of-its-kind, four-day event brought together a diverse group of military and civilian participants to study and understand better the impact of high-intensity urban conflict on civilians. At the same time, the exercise stress-tested NATO’s Protection of Civilians policy.1 Note: There are currently no plans to review the 2016 NATO Protection of Civilians (PoC) Policy. See North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), “NATO Policy for the Protection of Civilians,” (Warsaw: June 2016), https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_133945.htm. The findings and recommendations in this report are those of the organisers – PAX and Stimson – and are based on monitoring and evaluation data provided by the Cordillera Applications Group and feedback from 1 GNC and civilian participants.

Protection of Civilians

The NATO Protection of Civilians Handbook2 Note: NATO Allied Command Operations (ACO), “Protection of Civilians ACO Handbook,” (2020), https://shape.nato.int/resources/3/website/ACO-Protection-of-Civilians-Handbook.pdf. states that Protection of Civilians (PoC) ‘includes all efforts taken to avoid, minimise and mitigate the negative effects that might arise from NATO and NATO-led military operations on the civilian population and, when applicable, to protect civilians from conflict-related physical violence or threats of physical violence by other actors, including through the establishment of a safe and secure environment.’ Key to the NATO PoC Military Framework3 Note: NATO Military Committee, “Military Committee Concept for the Protection of Civilians – PO (2018) 0227,” (2018). is the emphasis on ‘Understanding the Human Environment (UHE) – “a population-centric” view, focusing on the population’s perception with regards to the safety and security of their environment, including what they perceive as threats.’ NATO identifies three lines of effort when protecting civilians: Mitigating Harm (MH), Facilitate Access to Basic Needs (FABN), and Contribution to a Safe and Secure Environment (C-SASE). The TTX was designed to experiment with these concepts and the guiding documents NATO has developed since adopting its PoC Policy in 2016,4 Note: NATO, “NATO Policy for the Protection of Civilians,” (Warsaw: June 2016), https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_133945.htm. within the particularly demanding context of urban military operations

Near Peer conflict

NATO’s PoC Handbook confirms that Protection of Civilians is relevant to all of NATO’s three core tasks – Collective Defence, Crisis Management, and Cooperative Security – and applicable to all NATO and NATO-led missions. When applying PoC in past years, the emphasis has often been on military contributions to the protection of civilians in out-of-area missions and NATO forces facing asymmetric threats. Given the Alliance’s shift in focus back to Collective Defence, the TTX was designed to experiment with the application of protection of civilians in a scenario where NATO faces a near-peer adversary.

Urban warfare

According to the United Nations, by 2050, 68 per cent of the world’s population will live in urban areas.5 Note: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, “2018 Revision of World Urbanization Prospects,” (16 May 2018), https://www.un.org/development/desa/publications/2018-revision-of-world-urbanization-prospects.html. This trend will have real implications for those who wage war and civilians living through war. NATO security forces must prepare to conduct future operations in the urban space and understand and mitigate the effect of their operations on civilians. The Alliance has demonstrated some foresight in identifying and preparing for these new challenges, including developing policies and doctrine on urban warfare.6 Note: For more information, see: NATO Allied Command Transformation (ACT), “NATO Urbanization Project 2035,” https://www.act.nato.int/activities/nato-urbanisation-project. The TTX was designed to experiment with practical skills and knowledge needed to mitigate the impact of urban operations on civilians, civilian spaces, and critical infrastructure while also attempting to understand better the nexus between the Alliance’s PoC and Resilience policy and how resilience factors affect the ability to protect.

Civilian-Military Cooperation

Civilians deserve protection as well as information about and acknowledgement of the harm that befalls them and their community during conflict. Therefore, PAX and Stimson engage national and international military and civilian institutions to develop and strengthen civilian protection policies and their application during the planning, conduct, and analysis of missions and operations. NATO has acknowledged the importance of involving non-military subject matter experts (SMEs) throughout the development of its PoC Policy (2016), Military Framework (2018), and Handbook (2020) and has relied on civilian SMEs in the development of several PoC-related courses and exercises in recent years. In the same vein, PAX and Stimson offered to develop this TTX so that civilian organisations and military actors – NATO and others – could replicate variations of the TTX with mixed civilian and military participants.

Background

The multi-domain, Article 5 PoC wargame in an urban battlespace was commissioned in March 2021. The urban littoral environment was selected as it represents the most challenging future Collective Defence scenario for NATO. PAX and the Stimson Center recruited an international team of urban and future warfare SMEs from the Cordillera Applications Group, led by well-known strategist and author Dr David Kilcullen. Together, we designed and delivered the wargame. NATO’s 1 GNC agreed to host the event and provided the training audience and logistical support, including facilities, communication, IT systems, and exercise mapping for the wargame.

During the September 13, 2021, Initial Planning Conference, the aim of the exercise and the training objectives were confirmed, as were the scenario/vignette documents and the wargaming methodology. To support the TTX, Allied Command Transformation graciously authorised the use of their Archaria scenario, while the NATO Modelling and Simulation Centre (M&S COE) permitted the use of the WISDOM synthetic model. Fabaris S.p.A. provided IT support and scenario refinement.

Upon the conclusion of the Final Planning Conference on October 20, 2021, a training day was provided to the headquarters on the scenario and associated documents. PAX had trained 1 GNC on NATO’s PoC policy and framework in February 2021, so the command felt there was no requirement for refresher training on the subject.

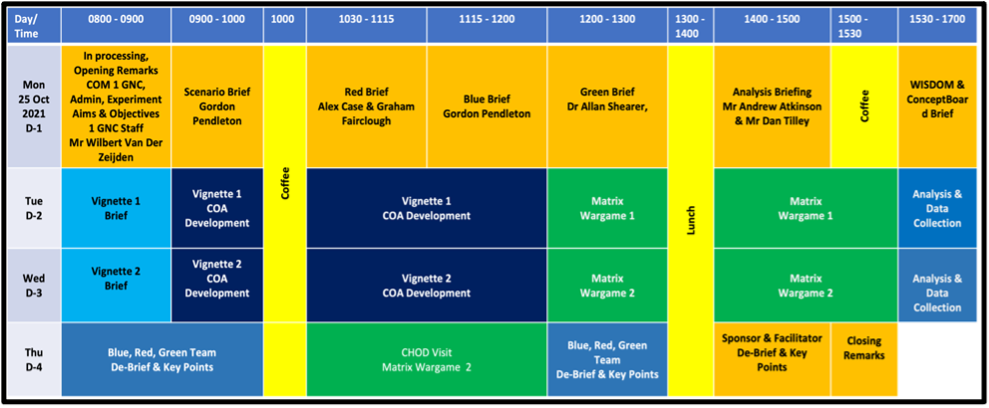

The event was held between October 25–28, 2021, in Munster, Germany, at 1 GNC’s Headquarters. Day 1 comprised introductory presentations regarding the scenario and training audience familiarisation with the Wisdom platform and Concept Board interactive planning tool. Days 2 and 3 were focused on wargaming, with day 4 dedicated to data presentation and discussion and a visit by the German and Dutch Chiefs of Defence. The TTX schedule is shown in Figure 1.

Wargame Aims and Objectives

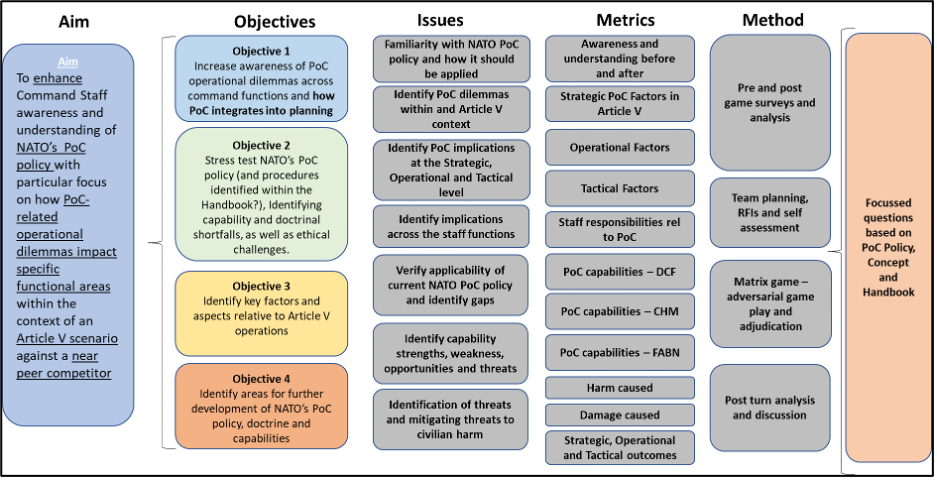

The focus of the TTX was not on establishing the dominating course of action (COA) or evaluating the training audience on their command of the primary subject matter. Instead, one of the primary aims of the PoC matrix wargame was to enhance command staff awareness and understanding of NATO’s PoC policy and, more importantly, its Military Concept. The training audience was essentially a tool through which we attempted to understand better how PoC-related dilemmas affected specific functional areas within an Article 5 scenario against a near-peer competitor during a high-intensity, urban conflict, all within the territory of a NATO Ally. The prioritised wargame’s aims were formulated as follows:

- Increase awareness and understanding of PoC dilemmas across command functions, with a significant focus on the more operations-centred staff elements, including the intelligence, current operations, and planning functions.

- Stress test NATO’s PoC policy and concept, as well as the procedures within the Handbook, capturing capability and doctrinal shortfalls, as well as ethical challenges.

Scope

The level of gameplay was operational to tactical, with COA development conducted by the 1 GNC Blue Team. There were no continuous time evolutions in the wargame and no requirement to synchronise operational/tactical actions across the three vignettes. The game focused on Blue Team using NATO current capabilities against a current, near-peer Opposing Force (OPFOR – Red Team), using familiar capabilities in a future 2025 context. The game was limited to the scenario and a future urban littoral city permitting concurrent multi-domain offensive/defensive operations, Humanitarian and Disaster Relief (HADR) efforts, and stability operations.

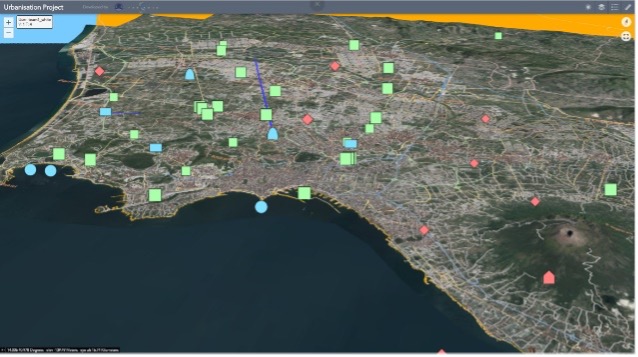

The scenario and the WISDOM model visualisation tool (see figures 2 and 3) depicted the urban environment. The latter provided various characteristics of a given urban environment and was an excellent basis for COA planning and wargame play. The three vignettes of the wargame were characteristic of the type of military operations expected in a multi-domain, urban environment within an Article 5 context and in the presence of large civilian populations. The NATO force organisation was baselined on open-source current capabilities, force structure, and doctrine. Capability cards and Rules of Engagement (ROEs) represented the 2025 force structure. The time for developing a COA during the wargame was compressed from typical planning timelines; however, it was sufficient for high-level planning and to gain relevant insights for analysis purposes.

Though most Blue Team actions were land-based urban activities, all operations were considered joint with coordination and synchronisation of effects sought across multiple domains. NATO force density and structures were not directly tested, though they affected how capabilities were played, resulting in identified conceptual gaps. The overall sustainability of the campaign was not assessed, but the analysis identified some vulnerabilities.

Objectives

The principal objectives of the wargame were as follows:

- To increase awareness of PoC operational dilemmas across command functions and how PoC integrates into the planning and conduct of operations.

- Apply and stress test NATO’s PoC approach, identifying capability and doctrinal shortfalls and ethical challenges.

- Identify critical factors and aspects relative to Article 5 operations (i.e., both hybrid and high-intensity conflict) in an urban area, including the impact of combat operations on national resilience levels and how that affects civilian protection.

- Identify areas for developing NATO’s PoC policy, doctrine, and capabilities.

These objectives were supported during the conduct of the wargame by player activity that considered:

- Human-centric threat assessments: Identification of the threats and risks to the civilian population and how these relate within the context of the urban operating environment and the overall mission.

- Civilian Casualty (CIVCAS) evaluation and mitigation process: Development of methods to assess CIVCAS (immediate and reverberating effects) and assessing the importance of measuring PoC effects concerning military planning and conduct of operations.

- Mitigate Harm (MH) to civilians from OWN actions: Assessment of potential threats and risks generated by NATO’s actions, and plan and conduct operations that mitigate civilian harm from these actions, including reverberating effects.

- Mitigate harm to civilians from OTHERS’ actions: Assessment of potential threats and risks generated by other actors and the impact of such actions on the civilian population and the operational situation. Plan and conduct operations that, where necessary, mitigate civilian harm caused by the actions of others, including the use of kinetic and non-kinetic effects.

- Facilitate Access to Basic Needs (FABN): Assessment of the importance of supporting efforts related to providing basic needs favouring the civilian population, the relevance to the overall military mission, and the relationships needed to assure basic needs are provided.

- Resilience and PoC Nexus: Analysis of how the two concepts interact with and affect one another, particularly how resilience shortfalls can undermine protection efforts, and attempt to identify potential mitigation measures.

Focus on the Protection of Civilians

The focus of the wargame was to expose the training audience and external participants to the dilemmas and challenges associated with high-intensity urban warfare against a near-peer competitor. That said, the TTX very much kept a PoC core focus, attempting to identify the specific protection issues related to such a complex operational environment. In particular, the wargame focused on:

- Defensive vs offensive operations.

- Identifying tasks across all relevant military functions.

- Providing a comprehensive training support group involving relevant military actors from within the Alliance, international organisations, the military, non-governmental organisations, and ministerial representatives.

- The relevance of incorporating civilian perspectives in military planning for PoC.

Where possible, the wargame also focused on:

- Reflections on using a Civilian Casualty Mitigation Team (CCMT) in the scenario.

- Reflections on the need to develop PoC relevant Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs).

- Recommendations from the TTX experience on the need for PoC mainstreaming in general and the pros and cons of PoC specialisation by units, HQs, or Allies.

Data Capture & Analysis Plan (DCAP)

The purpose of the wargame DCAP was to collect qualitative and quantitative data in a structured manner that would provide evidence to support the research findings. The DCAP took the aims and objectives set by the lead researchers and ensured that the vignette design would stimulate the gameplay to answer the questions posed by the objectives. The design team created a detailed DCAP that collected data at HQ 1 GNC throughout the wargame. The outline for the DCAP and its purpose is shown in Figure 4. This approach ensured that data was collected throughout Blue COA development and wargame play.

Additionally, the Requests for Information by Blue to Red and Green were all captured in an Excel spreadsheet and analysed. Lastly, the lead analyst ran a comprehensive data capture session at the end of each vignette, where Blue, Red, Green and the Wargame Control teams provided input to the data capture and the contributions from the external participants. The purpose of the session was to provide a specific focus on the wargame objectives using the PoC concept framework, the seven NATO baseline requirements for national resilience, and focus questions on the implications for NATO Article 5 operations.

Wargame Design

The wargame primarily employed a discovery methodology. This approach emphasised creativity by maximising opportunities to think about and discuss operations in the urban littoral environment, using NATO capabilities while analysing the effects of military operations on the civilian population. Conclusions made from the data collected must be interpreted to understand this research design in mind. Data was provided through a series of post wargame turn analysis sessions and linked study questions set against the wargame objectives:

- Wargame players were asked to develop COAs using current NATO joint capabilities and from the Red (Opposing Force) and Green (Host Nation authorities and local security forces) country books.7 Note: These country books contained information regarding the adversary and host nation, across the Political, Military, Economic, Social, Infrastructure and Information (PMESII) domains.

- Tasks were issued to players in the form of an overarching NATO Joint Force Command Operational Order and Commanders’ Critical Information Requirements. This was supported with a set of NATO Strategic documents, individual country Intelligence Summaries (INSTUMs), Order of Battle, ROEs, and vignette briefs. A Green Team of SMEs and external participants provided civilian input. The Blue Team produced implied and essential tasks from those given. Some of these tasks were challenging, given the nature of the environment and restrictive ROEs.

Scenario

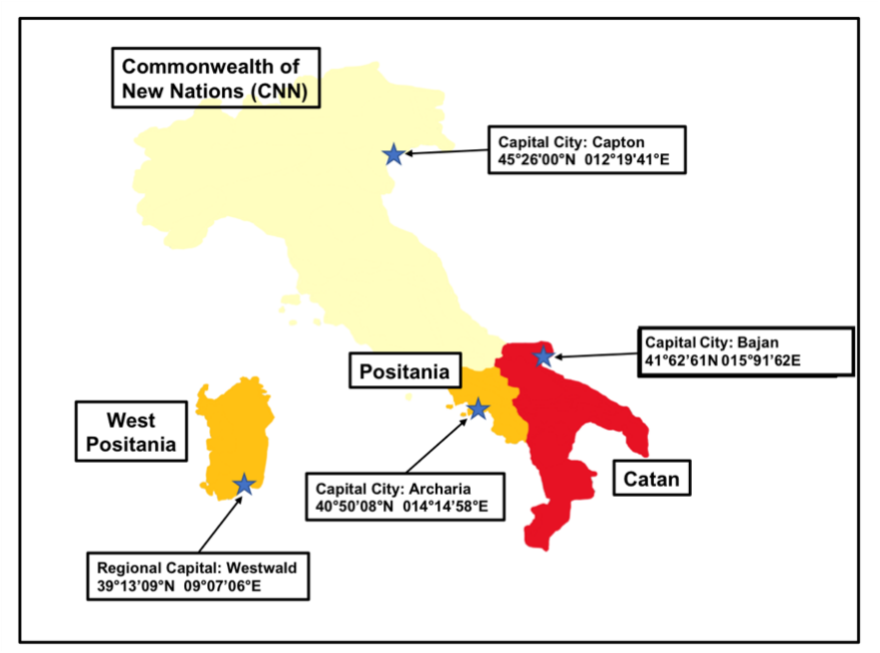

The wargame used a newly developed scenario for a NATO Article 5 multi-domain operation against a near-peer adversary. The fictional NATO member—Positania—was in the eastern Atlantic, approximately 4,263 km (2649nm) west of Portugal, and surrounded by the countries of Catan (CAT – Red Force) and the Commonwealth of New Nations (CNN, an initially neutral player), as depicted in Figure 5. Most of the offensive and defensive urban operations were based in and around the Positanian Capital of Archaria, with a population of 5.7 million and large numbers of refugees and Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs). The start state for the wargame was an invasion of Positania by Catan (Figure 6). NATO Blue forces were initially deployed east of the City of Archaria but by STARTEX had retreated into the city to create a suitable civilian, military, and political crisis requiring a PoC approach. Not all NATO forces were deployed at STARTEX, and the Corps HQ – 1 GNC – had to accommodate follow-on forces that arrived over 30 days. The start state was reset at the beginning of each vignette.

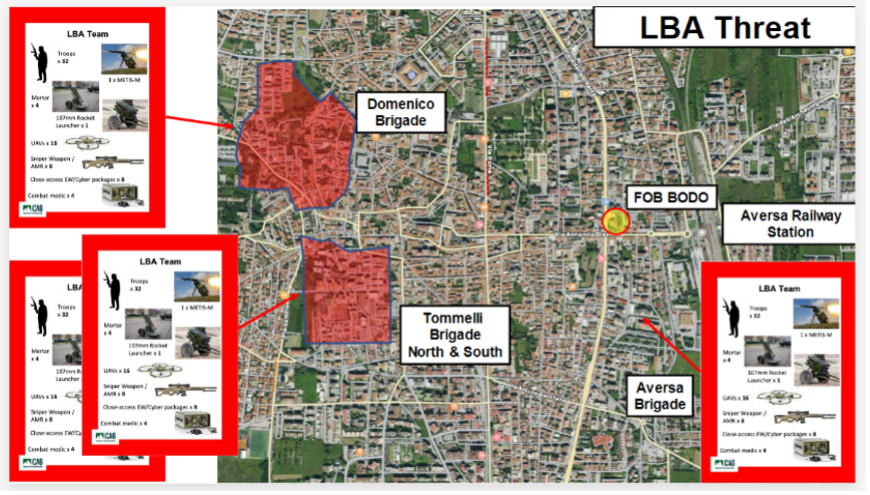

The operational context was rendered even more complex by a hostile Catan minority placed within various areas of the city of Archaria. The CAT State leveraged and radicalised elements of this ethnic group, effectively employing them as a proxy terrorist group called La Brigata Alba (LBA, refer to Figure 7 regarding LBA geographical distribution and capabilities). Other non-state armed groups were also employed, including large and influential organised crime groups which posed a significant threat to Host Nation (HN) and Allied operations and stabilisation efforts, particularly within the rear area of the combined force. This allowed the wargame to pose both conventional and asymmetric challenges to the Blue Team while maintaining a high level of realism regarding future urban warfare.

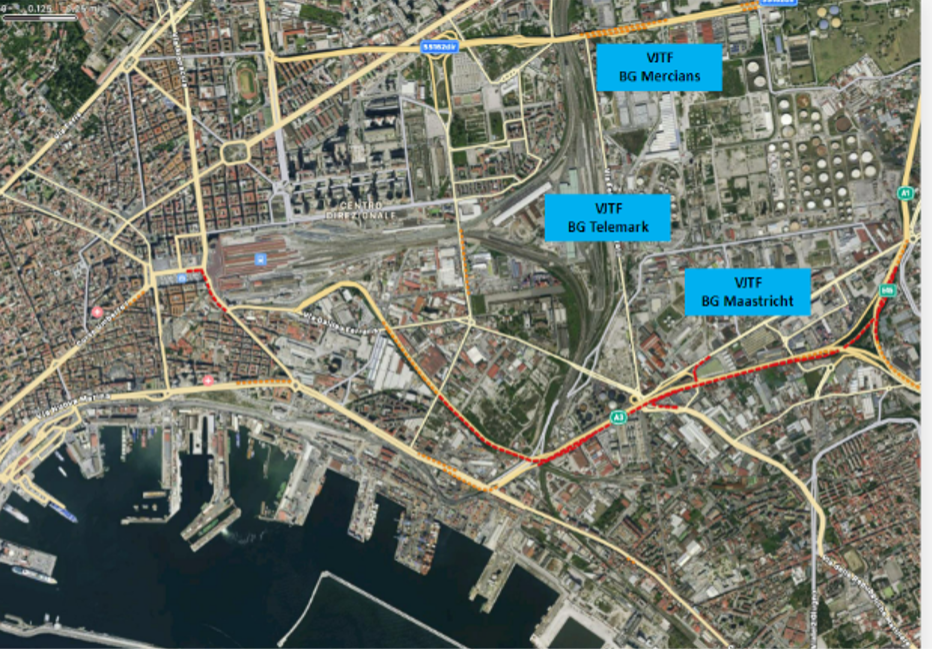

The wargame used the WISDOM urban model (see Figure 8) to support the scenario and planning process. In 2014, a requirement for an Intelligence Preparation of the Battlefield (IPB) visualisation tool for a dense urban environment was identified to support the NATO Urbanization 2035 Concept and wargaming programme. The NATO Modelling and Simulation Centre of Excellence in Rome built the subsequent WISDOM model.

The University of Naples provided base level city data to create the model. In addition, the Italian Carabinieri provided social, criminal and traffic data to assist with creating a human and pattern of life dimension within the model. The population density and size of the city was also increased from a population of 1.8 million to 5.7 million, and all the identified problem sets of a future urban environment identified in the NATO study were added. This resulted in over 250 data layers sitting within a 2D and 3D Esri ArcGIS model. It should be noted that the WISDOM model currently does not offer support for simulation, but Blue, Red, and Green forces can be displayed in the model and moved per a developed course of action to support wargaming. For the PoC wargame, additional population and ethnic breakdown figures were created to allow for a more realistic PoC scenario and ensure that resiliency factors could be played out during COA development.

Vignettes

Three vignettes were played out during just over two days of gameplay.

Vignette 1

Vignette 1 was a NATO defensive operational scenario in a complex and confined urban environment against a near-peer adversary without a full NATO force deployed in theatre. It started at D+8 (8 days after the start of Allied operations) with 1 GNC deployed in theatre with limited Allied forces on the ground and in retreat. Significantly, Blue had to consider the protection of civilians—citizens of a NATO country—the impact of their defensive operations on the local population and host nation Government concerns. Blue also faced a hostile ethnic minority in the urban environment supporting OPFOR Special Operations Forces (SOF) and a terrorist insurgency.

The vignette’s primary purpose was to lead the training audience to use force to mitigate harm to civilians from the actions of others (NATO PoC military framework, lens 1, Mitigation of Harm), despite the challenging urban setting.

Vignette 2

In Vignette 2, the scenario had moved forward to D+31, and most Allied forces had deployed into theatre. NATO Blue Forces had commenced joint, multi-domain, offensive operations against the Catan invasion as well as counterterrorism operations against the LBA terrorist groups. The level of refugees and IDPs had increased for this vignette, and several political developments had provided additional dilemmas for the NATO Force. Additionally, attacks on the main port had increasingly reduced the flow of food and humanitarian assistance and reduced the Alliance’s Reception Staging and Onward Movement (RSOM) capacity.

This vignette proved particularly challenging, as it required the planning and conduct of offensive operations in built-up urban areas (NATO PoC military framework, lens 1 – Mitigation of Harm) while supporting humanitarian operations (NATO PoC military framework, lens 2 – Facilitating Access to Basic Needs), and supporting HN-led stability operations (NATO PoC military framework, lens 1 – Mitigation of Harm and lens 3 – Contributing to a Safe And Secure Environment). Of particular interest was a mass casualty event in the Allied rear area, where a large-scale missile strike targeted an Allied staging area where forces had amassed in preparation for a planned offensive operation. As the military units formed up in one of the cities’ ports, their proximity to civilian buildings led to significant civilian casualties and damage to essential services and infrastructure. This event highlighted numerous challenges linked to the conduct of urban operations, including the challenges of massing troops in an environment where there are limited locations; the use of Explosive Weapons in Populated Areas (EWIPA); and various resilience considerations, including the ease with which national medical responses can be easily overwhelmed, how to effectively communicate with the local population, and how to mitigate risk to critical national infrastructure.

Vignette 3

At D+45, Allied forces had continued to hold the initiative and maintain offensive momentum, liberating some of the city and definitively halting any further Red Force advance, with the Catan military decidedly on the back foot. Blue Team was again tasked with an offensive operation, specifically, clearing a district within the capital where adversary forces had established a stronghold for some time. The area in question was majority Catan and was considered hostile to both host nation and NATO forces. For this reason, the operation was to be considered particularly delicate. This vignette required the application of all lenses of the NATO PoC framework, with special emphasis on the challenge of anticipating and mitigating harm from the actions of others.

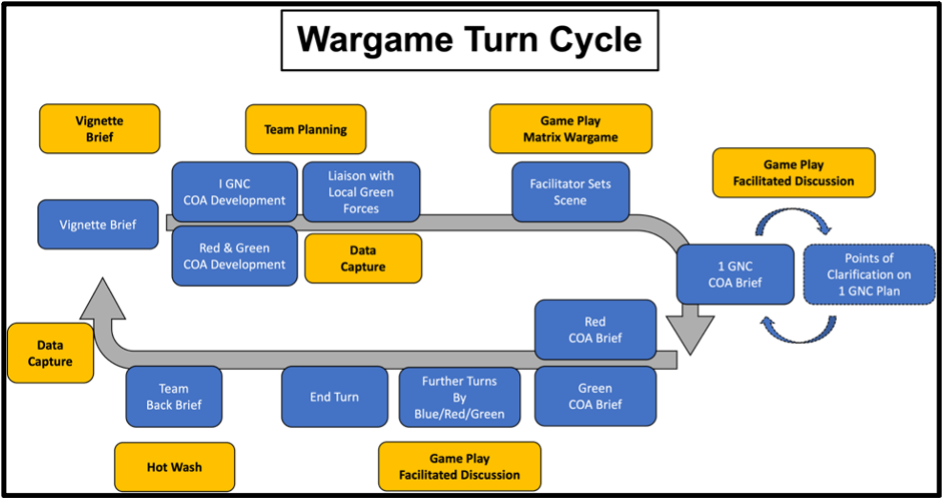

Process

Each vignette was delivered similarly (Figure 9), starting with a briefing, COA development, facilitated gameplay, hotwash8 Note: Post-event de-briefing. , and data capture. The first and second vignette lasted for a day, while the third was delivered within a more limited timeframe to accommodate the visit of the German and Dutch Chiefs of Defence.

Following the vignette brief, each team (Blue, Red, and Green) retired to their assigned planning spaces to develop their respective COAs. Upon completing this task, all participants returned to the principal planning room and presented the key aspects of their plan, with external participants in attendance. The briefing order was always the same: 1 GNC training audience, then the opposing force, and finally the HN team. Following each presentation, all participants were allowed to propose questions of fact (with the sole purpose of gaining greater clarity on the briefed COA, but in no way were they allowed to challenge it at this stage of the game). Once each team had presented, Dr Kilcullen led the facilitated discussion during which all attendees were encouraged to participate. Upon completion of this phase, the Data Capture team would summarise the key issues raised and a synopsis of the key takeaways from the session. Once again, all participants were encouraged to provide additional input or recommendations.

Participants

Despite participation limitations imposed by local COVID restrictions, the event included 40 participants and observers from the following entities:

- 1 GNC

- PAX

- Stimson Center

- NATO HQ

- NATO SHAPE

- NATO ACT

- NATO LANDCOM

- CIMIC Centre of Excellence

- UN WFP

- Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC)

- Finnish Defence Force International Centre (FINCENT)

- German Ministry of Defence

- Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- ICRC (Observer)

It was initially planned to open the event to online participation, but IT issues rendered this solution impracticable.

Blue Team

1 GNC provided the Blue Team from across the J1-J9 functions. Depending on the nature of the vignette, Blue provided the action and the reaction or the counteraction with the capabilities provided and within the assigned ROEs. Blue provided both hotwash and post-vignette reviews and were asked to evaluate their capabilities and impact of their COA on the PoC framework in post-adjudication. Additionally, they were asked to identify areas for conceptual development and highlight ethical factors.

Red Team

The Cordillera Applications Group (CAG) provided a Red Team composed of three individuals functioning as specialists in the Land, Air, and Cyber domains. Red conducted its planning cycle, COA evaluation and delivery of its operational plan to provide a realistic Opposing Force (OPFOR). It consciously isolated its planning from Blue to provide a realistic threat and scheme of manoeuvre. Depending on the nature of the vignette, Red provided the action, the reaction, or the counteraction. Red also contributed both hotwash and post-vignette reviews and evaluated its effect on the PoC.

Green Team

PAX for Peace, Stimson Center, CAG, NATO SHAPE, NATO HQ SACT, NATO Human Security Unit, the UN (United Nations) World Food Programme, and the Center for Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC) provided the Green Team. Green conducted its planning cycle, COA evaluation, provided realistic host nation, military/civil coordination to the Blue Team and created some PoC dilemmas for the training audience. Depending on the nature of the vignette, Green provided the reaction or the counteraction. Green inputted hotwash and post vignette reviews and evaluated its pre- and post-capabilities.

Key Observations

The vignettes and associated wargaming highlighted important lessons identified. These points have been derived from the integrated assessment of the PAX/Stimson TTX team and the analysis and observations of the Cordillera Applications Group. Input from the training audience has also been considered.

On Protection of Civilians

- Tactical decisions and actions which affect a civilian population’s security can quickly generate strategic effects, rendering comprehensive PoC a major consideration, especially within collective defense scenarios.Harm caused by NATO and the failure to address harm from other actors against Member State populations will adversely affect the political level and public support, undermine NATO’s center of gravity, and generate reverberating effects that weaken trust across the Alliance.

- While the military plays the most significant role in protecting civilians in a future conflict, NATO political actors have a role to play in understanding, prioritizing, and clearly communicating their intentions for the protection of civilians, including in future mission mandates and resourcing.

- While PoC experts can be stationed within the J9 to support end-users, understanding of PoC applications is essential within those elements that plan, prepare, and conduct operations. Failure to train specialists within these operations-focused functions will severely hinder PoC operationalization and jeopardize strategic outcomes in Collective Defense scenarios, just as they did in Iraq and Afghanistan. Put simply, PoC is not a Civil-Military Cooperation (CIMIC) task. It must be a core capability for the entire battle staff.

- The Blue Team confirmed it had limited exposure to the PoC Concept and Handbook prior to the TTX. This led to PoC issues being principally framed through a Mitigation of Harm from Own Action perspective.

- Blue struggled to develop approaches to mitigate civilian harm from the actions of others. One such example was when the decision was made to assign Green to conduct a close combat operation, with NATO forces relinquishing control of actions to mitigate the harm on civilians supporting Red. If Blue is to mitigate civilian harm from Red or Green forces, it must be emphasized that sometimes own kinetic combat action may be required (as defined in the PoC Handbook along with the attendant risks to the force and civilians). This is a common challenge also faced by nations involved in the training and mentoring of partner forces.

- Blue’s understanding of Civilian Harm included physical manifestations of harm: death, injury, and property damage. However, they seemed to exclude damage to critical infrastructure that could block access to essential services; psychological trauma, stress and fear; and the effects of military actions on civilian sentiments that could undermine mission support.

- This includes assessments on population density and movements, the contextual functioning of civilian spaces, critical infrastructure (particularly along the seven baseline requirements9 Note: Wolf-Diether Roepke and Hasit Thankey, “Resilience: the First Line of Defence,” (27 February 2019), NATO Review, https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2019/02/27/resilience-the-first-line-of-defence/index.html. ), context specific threats and risks to civilians. NATO’s PoC Framework and Handbook would have significantly facilitated Blue Team’s planning and execution, particularly their mitigation of adverse effects on the civilian population. Instead, the training audience found themselves naturally gravitating towards traditional military analysis approaches (PMESII10 Note: PMESII is the analysis of an operating environment through the Political, Military, Economic, Social, Information and Infrastructure lenses. See, for example: NATO Civil-Military Cooperation Center of Excellence (CIMIC COE), “CIMIC Handbook, Chapter V: Planning and Assessment,” (2020), https://www.handbook.cimic-coe.org/5.planning-and-assessment/5.3assessment/. ) rather than integrating them with UHE considerations. This unavoidably and often led to protection becoming an afterthought, relegated to the host nation and non-military actors. The understood risk is that civilian safety and security can become leveraged by military forces.

- Despite NATO forces taking all necessary precautions, CIVCAS will happen, and NATO forces must plan for proper response in coordination with the host nation. The TTX analysis suggested incidents will rise as Allied forces transition from a defensive to an offensive footing. Expectation management at the political level and strategic communication is critical. The training audience and 1 GNC leadership recognized the importance of Civilian Casualty Tracking and Mitigation (CCTM), as described in the PoC Handbook, and recognized the key contribution a CCMT provides. However, they also regularly noted a lack of investigative capability, which would, at a minimum, hamper the ability to understand operations’ impact on civilians and the lessons identified/learned process that is important to reducing future civilian harm.

- These could have complex repercussions regarding the impact on operational momentum. During the TTX, it was demonstrated that the adversary could declare ceasefires and humanitarian pauses with the simple goal of slowing down the Allied Force or negating a decisive action. This would put the military commander in a difficult position to either accept the setback or risk the strategic communication and political fallout from rejecting a temporary ceasefire.

- Challenges related to C-SASE will increase from a purposeful adversary switching to hybrid activities and from ongoing stress on society—particularly as competition for scarce goods and services increases, eroding adherence to law and order. (Urban populations are especially vulnerable compared with rural areas). Longer-term social divides will emerge, giving rise to potentially de-stabilizing effects that threaten social cohesion and longer-term peace and political settlements.

On Urban Warfare and PoC

- Combat operations in complex urban environments are likely in future conflicts. Blue took great lengths to avoid the urban fight under the assumption that they could decide where and when to engage. In a high-intensity conflict on an Ally’s soil, urban warfare will be unavoidable, elevating the risk to civilian life.11 Note: Dr. David Kilcullen and Gordon Pendleton, “Future Urban Conflict, Technology, and the Protection of Civilians: Real-world Challenges for NATO and Coalition Missions,” (10 June 2021), the Stimson Center, https://www.stimson.org/2021/future-urban-conflict-technology-and-the-protection-of-civilians/.

- Greater understanding needs to be developed about modern city landscapes’ intricate and complex challenges. This applies to both how this interdependent system of systems affects military operations and national abilities to respond to strategic shock and how the degradation of these systems affects the civilian population and its ability to secure basic needs and services.

- Societal diversity and complex dynamics in the urban space. The urban societal landscape is neither uniform nor homogenous. Instead, it is intricate, diverse, and complex, often leading to different acceptable political vs military endpoints within the same battlespace. Greater investigation on assessing gaps of perception and engaging a diverse urban population to achieve political and military outcomes is required.

- The mere presence of NATO forces within a highly urban environment can increase risks to civilians. The massing of large numbers of Blue Team troops generated a mass CIVCAS event, which led to considerations on the challenges connected with similar actions within an urban area and the associated dangers for civilians as they go about their daily lives.

- Large scale operations, mass casualties, and limited medical response capacity. The civilian casualty figures for the TTX were significant and indicative of a situation that NATO has never faced inside its territory. Two of the vignettes alone generated an estimated 66,000 civilian casualties, including 2,500 caused by Blue Team actions. While direct harm casualty rates will diminish, prolonged operations will overwhelm the medical system as famine, disease, and other crisis-related complications take hold.

- Civilians’ presence in the urban fight and military options. Civilians remaining within the urban space (by choice or not) will further complicate military planning, particularly where the number of remaining civilians and their estimated locations are unknown. Due to the nature of the urban area, identifying the presence of civilians within the combat space poses multiple challenges. It will potentially reduce military options available to commanders, including those that most modern western militaries consider critical to conducting operations, especially joint fires and general air support. The use of Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) for positive identification of targets or for confirming the presence of civilians may also become challenging due to potential jamming efforts from adversaries and the limited visibility the urban landscape often provides.

- Explosive Weapons in Populated Areas. EWIPA is of great concern and inevitably leads to civilian mass casualty events. While Blue Team practised the use of positive identification, this was complicated by the difficult urban battlespace. Additionally, adversaries may use EWIPA specifically to create such mass casualty events to complicate the front-line fight and hamper rear areas because of the flow of IDPs escaping EWIPA.

On Resilience and PoC

- Resilience is more than just military enablement. It became rapidly evident that resilience was more aligned to supporting the protection of civilians from further harm rather than the military mission. While it enables both, resilience is vitally important under a protection perspective and will be an HN’s primary concern, potentially even over military enablement. Greater analysis and attention are required regarding the connection between resilience and PoC12 Note: The Stimson Center and PAX are currently developing a paper on the intricate nexus between national resilience and the protection of civilians. The paper is expected to be published no later than the summer of 2022. For this paper and others related to NATO and the protection of civilians, refer to the Stimson Center’s website and its “Strengthening NATO’s Ability to Protect” project page: https://www.stimson.org/project/nato-civilian-protection/.

- Conflicting perceptions of national resiliency levels. It was important to note how HN and military assessments of national resiliency factors remained reasonably aligned during defensive operations, only to differ substantially after NATO-initiated offensive actions. This underlines the importance of ensuring constant close engagement and coordination between the HN and the military component and the risk of basing planning assumptions on incorrect or outdated analysis.

- Demands on food and water will become increasingly challenging. As the conflict intensifies, competition for limited resources will worsen amongst civilians. Also, the airport and seaport space between military and humanitarian actors will shrink, with the added likelihood of reduced logistical capacity due to infrastructure degradation from kinetic and cyber effects and congestion of highways, roads and waterways.

- Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) and response capacity. The number of IDPs in the initial stages of a crisis could be significant and rapidly overwhelm capacity. While engagement occurred between all stakeholders, this was not always as effective as it could have been, as military actors understandably became more focused on the traditional aspects of mission conduct with the increased intensity of operations. This, however, can lead to further complications as civil protection becomes compromised and the military finds itself reacting rather than pre-empting, co-planning, and potentially containing the development of humanitarian and political crises. Left unchecked, the movement of IDPs became an increasing challenge to Alliance and HN freedom of movement, as the host nation and humanitarians struggled to manage the situation, particularly when resources became depleted or degraded.

Recommendations

In our engagements with military actors, we sometimes hear that ‘PoC is a COIN exercise’. This could not be further from the truth. The mindset shift to high-intensity conflict and the acceptance of the inescapable reality of future urban conflict has not yet fully matured, nor are the strategic implications of failure to protect NATO populations fully understood. This was reflected in the difficulties the training audience encountered in integrating PoC considerations into the planning and conduct of military operations. These challenges can only be overcome through greater training opportunities (both collective and individual), increased visibility of existing PoC publications, and the drafting of additional NATO protection documents.

- PoC training objectives should be integrated into NATO exercises, at all levels and across domains, instead of being limited to crisis response scenarios. The TTX demonstrated that PoC problem sets are relevant to all NATO core tasks, including Collective Defence. PoC training objectives should be incorporated in all NATO exercises, interlinked with resilience, and they should highlight challenges within the urban context, particularly regarding second and third-order effects of operations. Greater focus on PoC in all NATO exercises would enhance participants’ training experience and provide greater visibility for the Alliance’s PoC framework and related publications. This would contribute to PoC becoming a core staff capability and not simply a subject delegated to CIMIC staff officers.

Regarding individual training, the emphasis should be on ensuring greater cross-functional participation. As a starting block for intelligence, operations, and planning staff, abbreviated, function-specific PoC courses should be developed to support this effort. Individual and collective PoC training should also seek to integrate high-intensity urban conflict while including resilience considerations from a civilian harm perspective. Most importantly, NATO training must stress, with greater emphasis, the potential need for the use of military force to mitigate harm from the actions of others, which continues to be a training performance shortfall.

- Existing PoC publications require greater visibility within the NATO Command and Force Structure. This begins with greater emphasis and support at all levels of leadership, from the political and diplomatic leadership of NATO HQs to Commanders of NFS entities. This effort should be bolstered by CIMIC functional areas across the Alliance and its leadership. Also, existing domain-specific doctrine should integrate PoC considerations into their planning and operations publications. According to point a. above, greater PoC training opportunities within NATO exercises will increase NATO PoC documentation visibility.

- There is a requirement for additional PoC publications. This includes the development of SOPs on such topics as Understanding the Human Environment and Threat/Risk Assessments, a dedicated publication on Civilian Harm Tracking and Mitigation (tailored to the unique challenges of Collective Defence in support of a NATO Member State), and PoC checklists for planners and current operations staff.

- ‘CDE (Collateral Damage Estimate) Zero’ aspirations for NA5CRO (Non-Article 5 Crisis Response Operations) have never been achievable and are even less so in the context of high-intensity, urban warfighting. Dialogue and expectations must be managed, especially at the highest political and military levels, to allow NATO the freedom to act proactively and remain in control of the strategic narrative to assure its Member States and their 1 billion citizens. Further, the setting of unrealistic CIVCAS limitations will negatively affect the transparency between Member States, as well as between governments and their respective populations, which will, in turn, undermine trust amongst all stakeholders.

- Within the urban environment, situational awareness on the numbers of civilians remaining in place will become challenging; measures and methods to track population densities will be critical in mitigating harm from NATO’s own operations. Innovative methods could include providing localised data and apps, e.g., civilian incident reporting systems, to support targeting decisions. Furthermore, close coordination and information sharing on the estimated location of civilians with international organisations and civil society will be essential, particularly if the HN’s capacity is degraded.

- There is a requirement to re-build capabilities and knowledge in the highly complex field of urban warfare, integrating a sound understanding of the elevated risk to civilian life and the strategic effects CIVCAS will play. The next significant challenge for the Alliance is to understand how to conduct modern, high-intensity warfare in urban areas while minimising the risk to civilians and critical civilian services. There is, therefore, the need to provide greater individual and collective training opportunities that address these problem sets, thereby favouring a timelier mindset shift. Also, doctrine, strategy and TTPs must be revised and updated to address these changes and emerging challenges.

- NATO Urban Warfare training requirement. A dedicated NATO Urban Warfare Planning and Operations Course, which should also address challenges related to protecting civilians for the strategic, operational, and higher tactical level, is needed. This individual training solution should also foster understanding of:

- The layered urban environment and how to exploit it from a defensive and offensive standpoint;

- The impact of the complex urban sub-systems on military operations and the civilian populations (including resilience considerations);

- The intricate and diverse human environment;

- and the impact of EWIPA and possible alternative weapon choices or mitigation measures.

This would be in addition to the more purely military subjects related to the planning and conduct of large-scale military defensive and offensive operations. Where possible, these training opportunities should be open to civilian participants to foster mutual understanding of the respective roles and responsibilities of the various stakeholders while also enhancing greater cooperation and coordination between military and civilian actors.

- Increase awareness and understanding of the critical linkage between resilience and PoC within both hybrid and warfighting operations in an Article 5 context. This nexus should be highlighted in both PoC and resilience policy, doctrine, and training and must be reflected in a mutually supportive manner.

- Rapid, early Civ-Mil coordination and deconfliction are required to identify IDPs and mass movement plans, noting that UN and International agencies may be mobilising at the same time as NATO. Attempts to do so in the immediate lead up to the crisis will most likely be a case of too little, too late. Barriers regarding information sharing must be overcome, leveraging already existing NATO policies. Security forces must be conscious that civil authorities and humanitarian actors may provide guidance and direction to fleeing civilians but have limited tools that will allow them to enforce these courses of action. Therefore, security actors must remember that coordination with civilian actors does not ensure that all things go to plan, just like military plans rarely survive first contact with the adversary. Therefore, continuous coordination and information sharing are essential to maintain situational awareness of how many civilians there are, where they are moving, and why.

- PoC as a core military function across J Codes. PoC operationalisation must not be buried in a J9 CIMIC effort, as it will not have access to key leaders, the requisite operational information, and the decision-making process. PoC SMEs should be placed within the Commander’s special advisory group (or the like) to promote cross-functional involvement, as is the case within HQ’s Allied Rapid Reaction Corps UK. Further, initiatives like LANDCOM’s PoC focal point training should be replicated and promoted as a best practice. Focal point training is lightweight, and if recommendations such as those outlined at point a., above, are followed, it can be effective enough to operationalise PoC, particularly where it truly matters.

- Investigative capability. At the start of any new mission, NATO should establish a Joint Investigation Analysis Team (JIAT) and a Civilian Casualty Mitigation Team (CCMT) like the ISAF model in Afghanistan but adjusted to the specific situation. The JIAT provides a critical ad-hoc investigative capability for key civilian harm events, while the CCMT is charged with tracking, analysing, and, significantly, liaising with external actors to provide recommendations to reduce civilian harm.

- Operational Liaison and Reconnaissance Team (OLRT). Prior to the mission, Operational Liaison and Reconnaissance Teams (OLRTs) should identify requirements linked to warfighting capabilities and support the Host Nation. In the latter case, while the military instrument may not solve all the challenges, it will make military decision-makers aware of restraints and restrictions while also providing critical insight for the political level.

Concluding Remarks

The TTX was an innovative experiment. Instead of framing protection of civilians in the traditional NA5CRO setting, the wargame, while remaining operations focused, successfully brought PoC considerations to the centre of a high intensity, Collective Defence mission played out against a near-peer competitor in SACEUR’s Area of Responsibility. While allowing the military audience to assess their urban operations skills, it focused on the strategic, operational, and tactical implications of these military actions on the civilian population. The event also successfully brought together a wide array of military and non-military actors, allowing all stakeholders to test assumptions regarding the subdivision of tasks and responsibilities, often leading to surprising realisations that may lead to more realistic planning efforts for future real-world operations. Too often, both parties have theorised on the role the other side would play in a high-intensity fight. While collective training efforts have attempted to test these assumptions, essential discussions on protection have usually occurred on the fringes of major exercise, often involving only the CIMIC specialists. This needs to change if both military and non-military actors wish to maximise the protection of civilians. This will become even more important in untested scenarios such as Article 5-type operations on NATO’s home soil where NATO allies are certain to run up against an array of challenges that neither the military nor their civilian counterparts are currently prepared for.

NATO Allies have not engaged in major urban conflict on their territory since World War II. While some lessons on protecting civilians and urban warfare have been identified over the past two decades, success in future urban warfare is far from certain and will require a better understanding of urban spaces and their inhabitants. In the conflicts of today and tomorrow, a city is not just a set of coordinates on a map. It is more than just the site of conflict. It is also a medium of conflict. Understanding the city and its inhabitants will be critical to the success or failure of a mission.

Protection of Civilians in today’s interconnected urban environments will require additional knowledge, skills, and capabilities. While NATO has made progress conceptually on urban operations and Protection of Civilians, the TTX showed a critical and timely need and opportunity to interrogate further where they overlap and are mutually supportive. While not empirical evidence, the experience of the TTX tells us there is more work to be done to build urban warfare capacity and awareness, understanding, knowledge, and skills from the high tactical up and across domains. A key part of that will be understanding how PoC and resilience tie into urban conflict and their collective strategic effects on the Alliance and the battlespace.

Notes

- 1Note: There are currently no plans to review the 2016 NATO Protection of Civilians (PoC) Policy. See North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), “NATO Policy for the Protection of Civilians,” (Warsaw: June 2016), https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_133945.htm.

- 2Note: NATO Allied Command Operations (ACO), “Protection of Civilians ACO Handbook,” (2020), https://shape.nato.int/resources/3/website/ACO-Protection-of-Civilians-Handbook.pdf.

- 3Note: NATO Military Committee, “Military Committee Concept for the Protection of Civilians – PO (2018) 0227,” (2018).

- 4Note: NATO, “NATO Policy for the Protection of Civilians,” (Warsaw: June 2016), https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_133945.htm.

- 5Note: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, “2018 Revision of World Urbanization Prospects,” (16 May 2018), https://www.un.org/development/desa/publications/2018-revision-of-world-urbanization-prospects.html.

- 6Note: For more information, see: NATO Allied Command Transformation (ACT), “NATO Urbanization Project 2035,” https://www.act.nato.int/activities/nato-urbanisation-project.

- 7Note: These country books contained information regarding the adversary and host nation, across the Political, Military, Economic, Social, Infrastructure and Information (PMESII) domains.

- 8Note: Post-event de-briefing. , and data capture. The first and second vignette lasted for a day, while the third was delivered within a more limited timeframe to accommodate the visit of the German and Dutch Chiefs of Defence.

- 9Note: Wolf-Diether Roepke and Hasit Thankey, “Resilience: the First Line of Defence,” (27 February 2019), NATO Review, https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2019/02/27/resilience-the-first-line-of-defence/index.html.

- 10Note: PMESII is the analysis of an operating environment through the Political, Military, Economic, Social, Information and Infrastructure lenses. See, for example: NATO Civil-Military Cooperation Center of Excellence (CIMIC COE), “CIMIC Handbook, Chapter V: Planning and Assessment,” (2020), https://www.handbook.cimic-coe.org/5.planning-and-assessment/5.3assessment/.

- 11Note: Dr. David Kilcullen and Gordon Pendleton, “Future Urban Conflict, Technology, and the Protection of Civilians: Real-world Challenges for NATO and Coalition Missions,” (10 June 2021), the Stimson Center, https://www.stimson.org/2021/future-urban-conflict-technology-and-the-protection-of-civilians/.

- 12Note: The Stimson Center and PAX are currently developing a paper on the intricate nexus between national resilience and the protection of civilians. The paper is expected to be published no later than the summer of 2022. For this paper and others related to NATO and the protection of civilians, refer to the Stimson Center’s website and its “Strengthening NATO’s Ability to Protect” project page: https://www.stimson.org/project/nato-civilian-protection/.