A new 7000-person survey conducted by phone in India between April 13 and May 14, 2022, finds:

- high levels of support for Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who likely remains among the most popular national leaders in the world today;

- extraordinary nationalist sentiment among Indians, at high levels compared to prior cross-national surveys using identical question wording;

- troubling signs of intolerance toward India’s large Muslim minority, which helps provide context to recent controversies;

- strong confidence in the Indian government’s ability to defend India against potential domestic and foreign threats;

- expectations among a majority of Indian respondents that the U.S. military would support India in the event of a war with China or Pakistan; and

- large majorities in favor of Indian numerical nuclear superiority against its adversaries.

The survey was intended to measure Indian attitudes towards the current government, India’s domestic challenges, and inter-state disputes as part of a broader Stimson Center initiative to understand the political incentives leaders face during interstate crises in southern Asia.1 Note: Also see Christopher Clary, Sameer Lalwani, and Niloufer Siddiqui, “Public Opinion and Crisis Behavior in a Nuclearized South Asia,” International Studies Quarterly 65, no. 4 (2021): 1064-1076. This nationally representative survey was translated and fielded in 12 languages for respondents in all 28 Indian states and 6 of India’s 8 union territories by the Centre for Voting Opinion & Trends in Election Research (CVoter).2 Note: The survey was fielded in English, Hindi, Punjabi, Gujarati, Marathi, Kannada, Malayalam, Tamil, Telugu, Oriya, Bangla and Asamiya. Given their small population size, the survey had no respondents in Lakshadweep or Andaman and Nicobar Islands union territories. CVoter is a widely used public opinion firm that regularly partners with Indian newspapers, magazines, television news channels, as well as academic researchers.3 Note: See, inter alia, ABP Live, “Are Voters Satisfied With Work Done By Govt In Poll-Bound States? ABP-CVoter’s Last Opinion Poll Ahead Of Elections 2022,” February 7, 2022, https://news.abplive.com/states/up-uk/who-will-win-up-punjab-uttarakhand-manipur-elections-2022-abp-cvoter-survey-important-questions-asked-to-people-ground-1511432; Times Now, “TIMES NOW-CVoter UP Poll Tracker: 43.1% people favour BJP, 29.6% lean towards SP,” July 17, 2021, https://www.timesnownews.com/india/article/times-now-cvoter-up-poll-tracker-43-1-people-favour-bjp-29-6-lean-towards-sp/786209; Republic, “Republic-CVoter Exit Poll Projection: NDA Will Cross Halfway Mark, Modi Set To Form The Government Again, Congress Likely To Fall Short Of 100 Mark,” May 19, 2019, https://www.republicworld.com/election-news/indian-general-elections/republic-cvoter-exit-poll-projection-nda-will-cross-halfway-mark-modi-set-to-form-the-government-again-congress-likely-to-fall-short-of-100-mark.html; and Nikhar Gaikwad and Gareth Nellis, “Do Politicians Discriminate Against Internal Migrants? Evidence from Nationwide Field Experiments in India,” American Journal of Political Science 65, no. 4 (2021): 790-806. CVoter also regularly provides electoral predictions in India’s notoriously volatile election landscape. While there have been accusations of bias on electoral predictions, a recent analysis found its polling is reasonably comparable in predicting winners and margins of victory (“Indian pollsters are doing fine. Here is how forecasts work,” March 27, 2022.) This project note outlines the key descriptive findings from the survey.4Note: With an overall sample size of 7,052, a conservative 95% confidence interval on categorical responses is 1.2 percentage points for the whole survey. Because this article uses subgroup analysis, the subgroup-specific 95% confidence intervals are displayed in the figures.

Political Support and Partisan Leanings

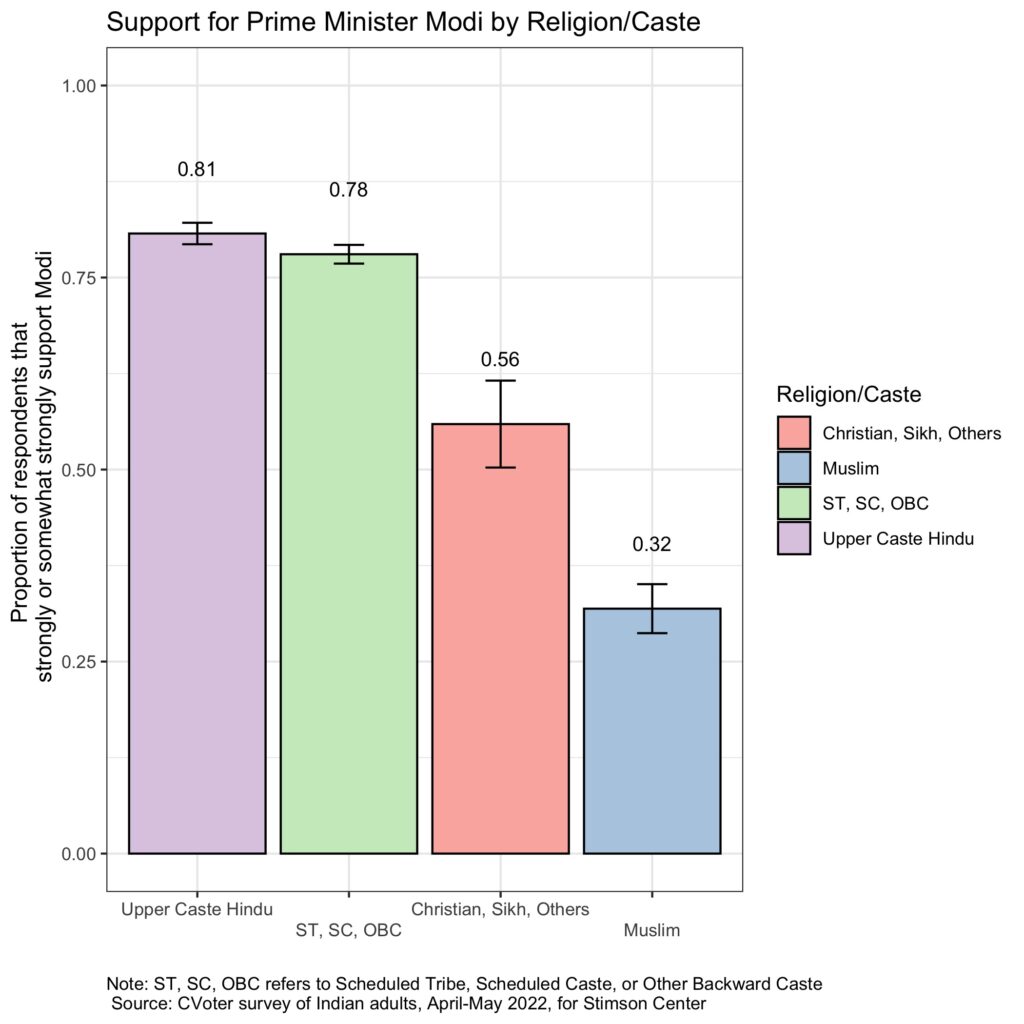

Prime Minister Modi received support from a large majority in our survey, with 71% either somewhat or strongly supporting him.5 Note: All results use post-stratification weights to make them comparable to the 2011 Indian Census. The Census allows us to adjust for population counts by age, gender, identity group (religion, scheduled caste, and scheduled tribe), and urban/rural status across states. This confirms a notable positive shift from last year when Modi’s approval levels were dampened by the COVID-19 crisis and challenged later in 2021 due to his government’s controversial farm laws.6 Note: Sumathi Bala, “Political setbacks dent Modi’s strongman image as India heads for crucial state polls,” CNBC, January 19, 2022. Support for his party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), was also high at 61%. Hindu respondents were significantly more likely to support Modi and the BJP relative to non-Hindu respondents in the sample (see Figure 1).

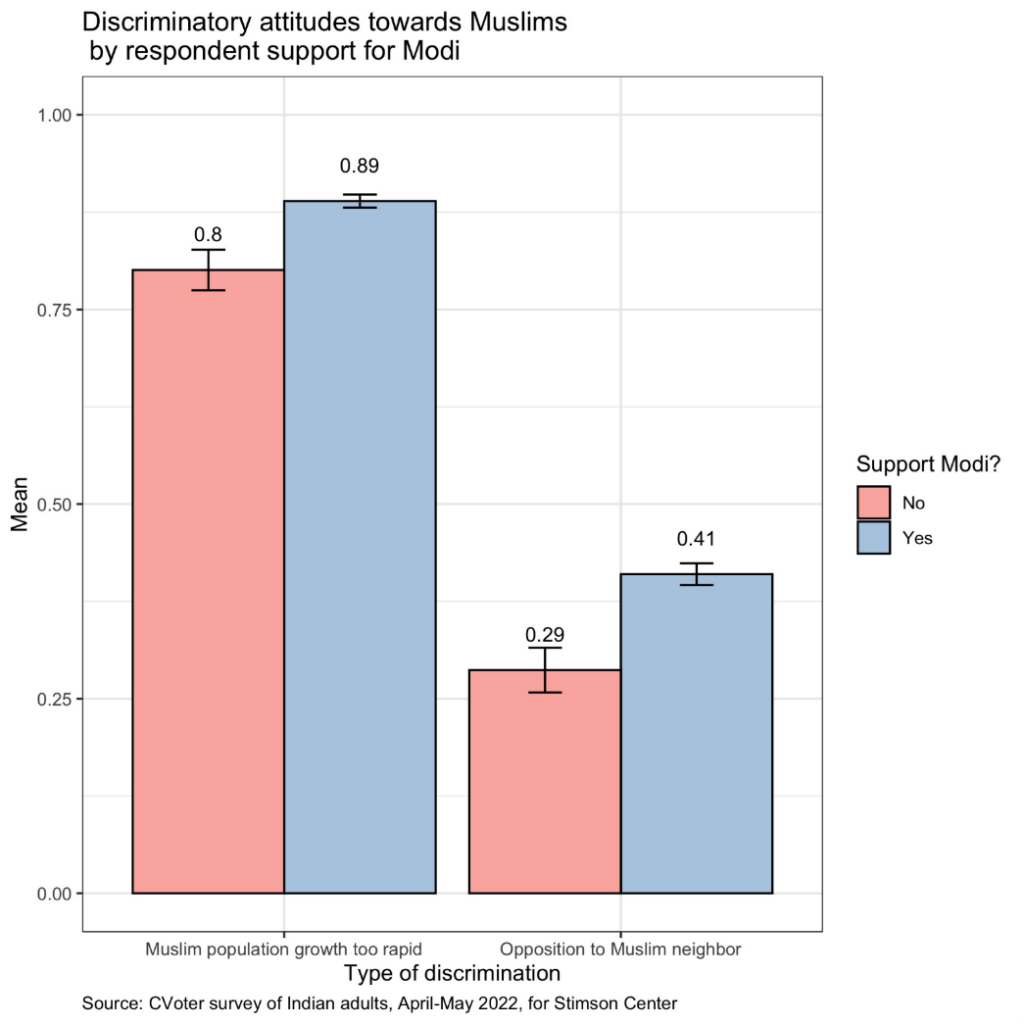

Worryingly, supporters of Modi or the BJP were more likely to express discriminatory attitudes toward Muslims, such as stating they did not want to have a Muslim as a neighbor or that they believed India’s Muslim population was growing too fast.7 Note: Our survey included experimental vignettes, but if a question was asked after the experimental vignettes, we have only including findings present in control condition as well as treatment groups. It is worth stating, however, that among all non-Muslim respondents, including both Modi supporters and skeptics, such discriminatory attitudes were widespread. An overwhelming majority of 78 percent of respondents stated that they believed India’s Muslim population was growing too fast. Such attitudes may explain why the historically secular Indian National Congress has publicly sought to disassociate itself from any “branding… as a Muslim party”8 Note: “BJP Managed to Convince People We Are a Muslim Party: Sonia Gandhi,” The Indian Express, March 10, 2018. and why other parties with nationwide aspirations, such as the Aam Aadmi Party, have also been accused of embracing a softer version of Hindu nationalist politics.9 Note: N. P. Ashley, “The AAP is not opposing the BJP precisely in the way liberals and radicals want,” The Indian Express, February 16, 2020. Such anti-Muslim sentiments could generate meaningful international repercussions if they influence national policy or political statements, a tendency which may be reflected in recent controversies. For example, India received considerable criticism from Muslim-majority countries following derogatory statements about the Prophet Mohammad made by BJP spokespersons.10 Note: Gerry Shih, “India Scrambles to Contain Fallout over Insulting Comments about Islam,” Washington Post, June 7, 2022. The U.S. government too has expressed concern about restrictions against and violence targeted at Indian religious minorities.11 Note: U.S. Department of State, 2021 Report on International Religious Freedom, June 2, 2022, https://www.state.gov/reports/2021-report-on-international-religious-freedom/.

Nationalism

Respondents were overwhelmingly nationalistic in their responses. 90% strongly or somewhat agreed with the statement that “India is a better country than most other countries.” This number, large in absolute terms, is also large when compared to other contexts.12 Note: This is slightly higher than a 2013 survey that found 82 percent of Indian respondents agreeing somewhat or strongly with this statement, making India the second most nationalist country by this measure (after Japan). “International Social Survey Programme: National Identity III – ISSP 2013,” https://search.gesis.org/research_data/ZA5950. U.S. citizens, for example, are typically viewed as more nationalist than average, but in 2014 only 70 percent of respondents strongly or somewhat agreed that the U.S. is a better country than most.13 Note: General Social Survey, “Agree America is a Better Country,” https://gssdataexplorer.norc.org/variables/4837/vshow. While American exceptionalism is a well-understood domain of study, self-perceptions of Indian exceptionalism are relatively underexplored.

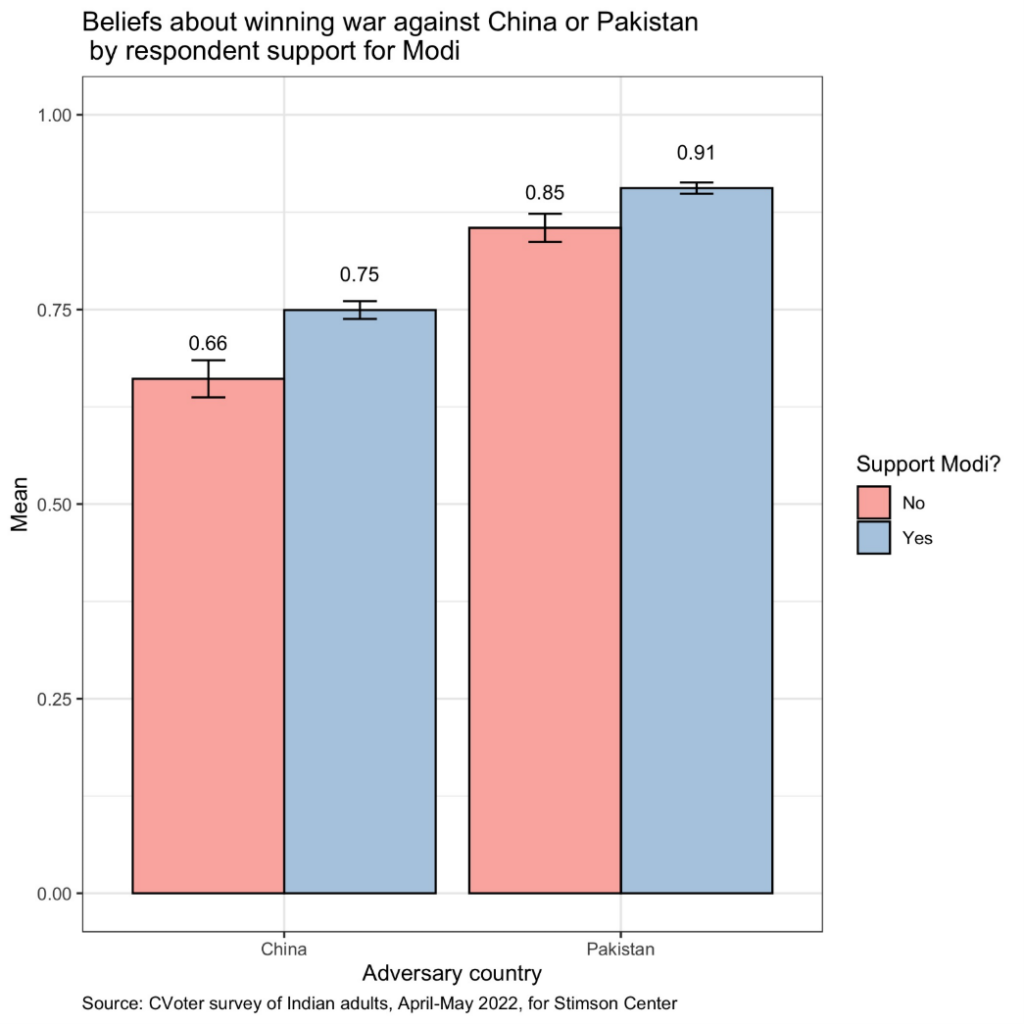

Nationalist sentiment dovetailed with negative opinions of neighboring countries. When asked about Pakistan, 67% of respondents expressed their “dislike to a great extent” and a nearly equivalent 65% “disliked” China to “a great extent.” These views covaried in intuitive ways, such that respondents with greater levels of baseline support for Modi were more likely to hold negative opinions of Pakistan and China, and more nationalistic individuals were also more likely to believe India could defeat China and Pakistan militarily.

A majority of respondents said that the United States would “definitely” or “probably” help in the event of an Indian war with China (56 percent) or Pakistan (59 percent).

Respondents in India’s south tended to have somewhat more favorable—though still overwhelmingly negative—views of China, but this north-south distinction was less evident in attitudes toward Pakistan. We find little evidence that unfavorable opinions toward China or Pakistan vary substantively by respondent age.

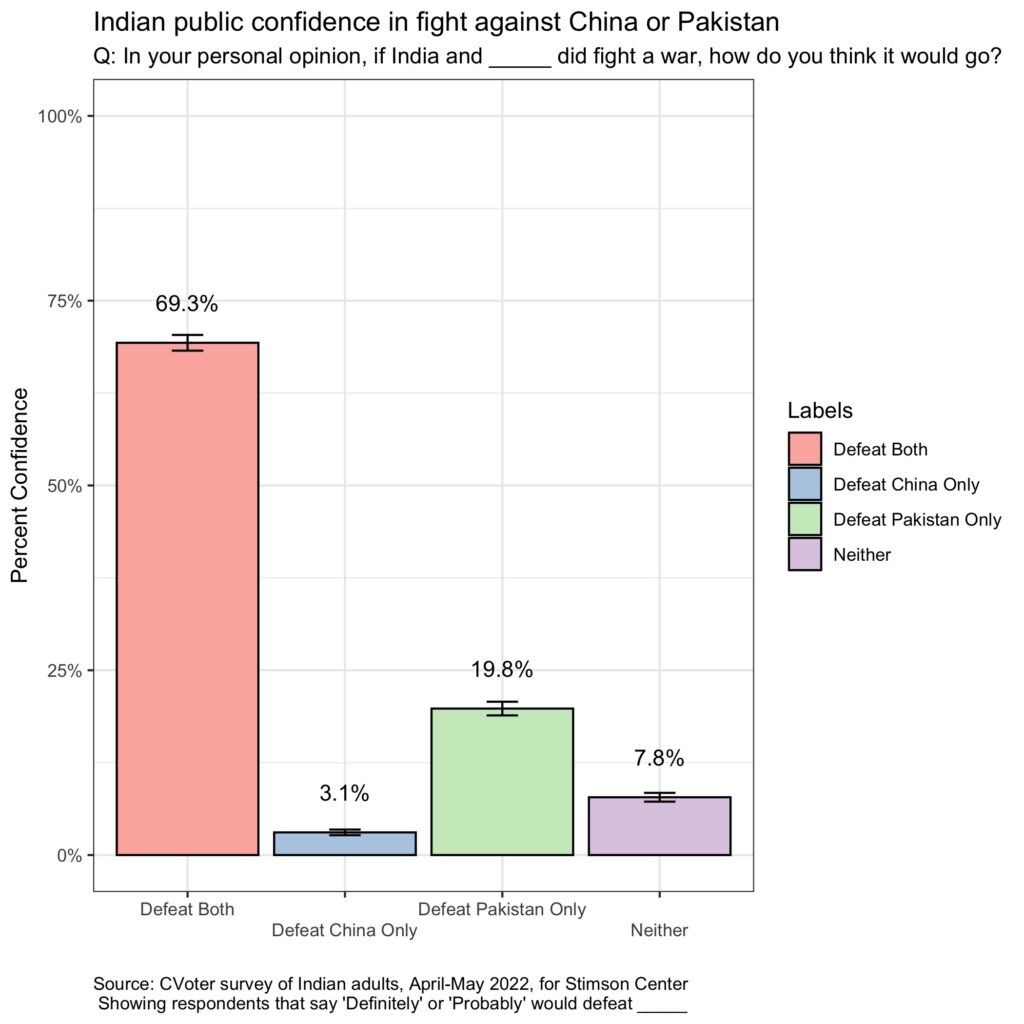

Nationalist sentiment also manifested as confidence in India’s military prowess and state strength. 90% of respondents said that India would probably or definitely defeat Pakistan in case of a war between the two hostile neighbors. A smaller, but still sizeable, percentage (72%) believed that India would probably or definitely defeat China in the event of a war. This may mirror confident public statements by Indian military officials,14 Note: “Army Chief MM Narvane talks tough on China: ‘We will win in case of war’,” ZeeNews, January 12, 2022, https://zeenews.india.com/india/army-chief-mm-narvane-talks-tough-on-china-we-will-win-in-case-of-war-2427377.html. but deviates from some expert analysis which suggests that India is likely at a disadvantage in a military contest with China.15 Note: Sushant Singh, “Why China is Winning against India,” Foreign Policy, January 1, 2021; Detesfra_ and Sim Tack, “China-India Border Crisis Has Quietly Resulted In Victory For Beijing,” The Drive, May 23, 2022. Modi supporters were modestly more likely to assess that India could defeat China or Pakistan than non-supporters.

Views of Indian Conflict Scenarios and Nuclear Weapons Needs

Respondents were divided about whether other countries would come to India’s defense in the event of an international conflict. A majority of respondents said that the United States would “definitely” or “probably” help in the event of an Indian war with China (56 percent) or Pakistan (59 percent), with a remaining large minority skeptical of U.S. aid in such scenarios. In contrast, surveys of U.S. respondents have found sizeable majorities might prefer to avoid entanglement in a Sino-Indian military conflict.16 Note: Vasabjit Banerjee and Timothy S. Rich. “Which side would the US public choose in an India-China conflict?,” The Interpreter, July 30, 2020, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/which-side-would-us-public-choose-india-china-conflict. For their part, Indian military leaders and strategists have stressed that India will have to fight its own wars alone without counting on others.17 Note: Asian News International (ANI), “India Has To Fight Its Own Wars, US Deployments According To Their Perspective: IAF Chief,” BW Businessworld, October 5, 2020, https://www.businessworld.in/article/India-has-to-fight-its-own-wars-US-deployments-according-to-their-perspective-IAF-Chief/05-10-2020-328212/; “Explained Ideas: Why India can’t depend on the US and EU to counter China,” The Indian Express, June 29, 2020, https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/india-china-border-dispute-the-ue-eu-6477314/; Kartik Bommakanti, “American military support to India is not automatic in China-India war. Delhi must know it,” The Print, July 22, 2020, https://theprint.in/opinion/american-military-support-to-india-is-not-automatic-in-china-india-war-delhi-must-know-it/466196/.

A similar majority of Indian respondents assessed China would come to Pakistan’s aid in the event of an Indo-Pakistani war (56 percent) and that Pakistan would come to China’s aid in the event of a Sino-Indian war (59 percent) consistent with Indian strategists’ fears of a “two-front war.” Combining these results shows that a large minority of respondents, roughly 4 in 10, foresee a scenario where India might have to fight both China and Pakistan simultaneously without U.S. help.

An overwhelming majority of respondents—68 percent—assessed India needed more nuclear weapons than its enemies.

We also asked about respondent views on the number of nuclear weapons India needs. An overwhelming majority—68 percent—assessed India needed more than its enemies. Just 13 percent said India should have about as many nuclear weapons as its enemies, and only a handful assessed that India should only have “a few” or “not any” nuclear weapons. These public preferences may be incompatible with India’s current nuclear force structure where most non-governmental organizations assess that China has more operational nuclear weapons than India while Pakistan has the same or slightly more nuclear weapons than India. 18 Note: Hans M. Kristensen and Matt Korda, “Indian nuclear forces, 2020,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 76, no. 4 (2020): 217-225; Kristensen and Korda, “Pakistani nuclear weapons, 2021,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 77, no. 5 (2021): 265-278; Kristensen and Korda, “Chinese nuclear weapons, 2021,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 77, no. 6 (2021): 318-336. If these preferences hold, they could serve as a political driver for an arms race with China, which U.S. assessments forecast could quadruple its nuclear forces to 1,000 weapons by 2030.19 Note: Office of the Secretary of Defense, Military and Security Developments involving the People’s Republic of China (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2021), 90.

Implications

The nature of Indian public opinion on national security issues and the effect of mass views on elite decision-making—which together determine the foreign policy “accountability environment”—remains remarkably understudied.20 Note: Vipin Narang & Paul Staniland, “Democratic Accountability and Foreign Security Policy: Theory and Evidence from India,” Security Studies, 27 (3), 2018, pp. 410-447. Yet our survey identifies several areas where public views may shape Indian government preferences in ways that will be important for India’s diplomatic partners to understand. Several implications appear most prominent from our analysis.

- No signs of erosion of Modi’s domestic political support: Our findings reaffirm other polls that show Modi is one of the most popular leaders—and perhaps the most popular leader—of any democratic country.21 Note: Also see Morning Consult, “Global Leader Approval Ratings,” https://morningconsult.com/global-leader-approval/ (updated June 9, 2022). This is true despite seeming missteps his government made in the face of the pandemic and associated economic travails.

- India’s extraordinary nationalism may prove challenging for Indian diplomatic partners to navigate: Status concerns are common in global politics, but the Indian polity appears to hold broadly a belief that India is better than most other countries. India’s Minister of External Affairs has popularized the idea that India will go “the India way.”22 Note: S. Jaishankar, The India Way: Strategies for an Uncertain World (Noida: HarperCollins Publishers India, 2020). Our findings indicate Indian citizens may perceive few reasons to compromise on issues like relations with Russia or its domestic institutions given India’s position in world politics.

- Widespread support for anti-Muslim attitudes may create domestic political incentives for anti-Muslim policies: Modi’s government has faced sustained allegations of anti-Muslim animus. Our survey results suggest that popular attitudes toward Muslims may encourage rather than halt any anti-Muslim impulses of the BJP-led government. Such sentiment could stoke friction between New Delhi and its neighbors and regional partners, a danger highlighted following recent anti-Muslim remarks expressed by members of the ruling party.23 Note: Anjali Ghodvaidya, “Mideast Oil Suppliers Condemn Insults on Islam by Modi’s Party,” Bloomberg News, June 6, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-06-06/mideast-oil-suppliers-condemn-insults-on-islam-by-modi-s-party.

- Indian self-confidence may lead to mistaken popular views of Indian military prowess: India has considerable military capabilities against its most likely regional opponents.24 Note: Christopher Clary, “Deterrence Stability and the Conventional Balance of Forces in South Asia,” in Deterrence Stability and Escalation Control in South Asia, eds. Michael Krepon and Julia Thompson (Washington, DC: The Henry L. Stimson Center, 2013); Frank O’Donnell and Alex Bollfrass, The Strategic Postures of China and India: A Visual Guide (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Kennedy School Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, March 2020). Yet Indian confidence that India would likely defeat China or Pakistan may exceed what a careful net assessment might warrant. This in turn might make it challenging for Indian leaders to back down in crises, since their publics may view such conflicts as winnable even if the military balance is not in their favor.25 Note: Daniel Kliman, Iskander Rehman, Kristine Lee and Joshua Fitt, “Imbalance of Power: India’s Military Choices in an Era of Strategic Competition with China,” Center for New American Security, October 2019, https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/imbalance-of-power.

- U.S. officials may seek to signal their willingness to aid India in the event of conflict with China to correct widespread popular doubts: A majority of Indians believe the U.S. would assist it in the event of a conflict with China or Pakistan. The United States likely could do more to publicly signal its reliability regarding a China contingency. The United States offered considerable material support to India in past crises with China (in 1962 and 2020) but both times cloaked some of that assistance in secrecy based on the requests of New Delhi.26 Note: “India asked Washington not to bring up China’s border transgressions: Former US ambassador,” Scroll.in, March 2, 2022, https://scroll.in/latest/1018580/india-asked-washington-not-to-mention-chinas-border-transgressions-former-us-ambassador-to-india. At the same time, U.S. officials likely do not foresee significant material support in the event of an India-Pakistan conflict and instead seek to retain a viable third-party crisis management role. U.S. officials should be aware that they may struggle to fulfill Indian public expectations in such circumstances.

- Public opinion may encourage rather than restrain any contemplated future Indian nuclear force buildup. Our poll finds an Indian public that prefers Indian numerical nuclear superiority against its adversaries by large margins. It is consistent with earlier public opinion research that suggested that the Indian public was comfortable with nuclear weapons as tools of statecraft in specific, plausible scenarios.27 Note: Benjamin A. Valentino and Scott D. Sagan, “Atomic Attraction,” The Indian Express, June 3, 2016. Such views help provide context to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s decision to emphasize on the campaign trail in 2019 that Indian nuclear weapons were not kept as mere showpieces.28 Note: He specifically stated that India’s nuclear weapons were not for use only in the Indian festival of Divali, commonly celebrated with fireworks displays. “Have we kept our nuclear bomb for Diwali, asks Narendra Modi,” The Hindu, April 21, 2019. Based on limited inquiries to date, further research is needed to untangle public understanding of nuclear weapons and their salience in contemporary debates.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Julia Lodoen for her research assistance.

Notes

- 1Note: Also see Christopher Clary, Sameer Lalwani, and Niloufer Siddiqui, “Public Opinion and Crisis Behavior in a Nuclearized South Asia,” International Studies Quarterly 65, no. 4 (2021): 1064-1076.

- 2Note: The survey was fielded in English, Hindi, Punjabi, Gujarati, Marathi, Kannada, Malayalam, Tamil, Telugu, Oriya, Bangla and Asamiya. Given their small population size, the survey had no respondents in Lakshadweep or Andaman and Nicobar Islands union territories.

- 3Note: See, inter alia, ABP Live, “Are Voters Satisfied With Work Done By Govt In Poll-Bound States? ABP-CVoter’s Last Opinion Poll Ahead Of Elections 2022,” February 7, 2022, https://news.abplive.com/states/up-uk/who-will-win-up-punjab-uttarakhand-manipur-elections-2022-abp-cvoter-survey-important-questions-asked-to-people-ground-1511432; Times Now, “TIMES NOW-CVoter UP Poll Tracker: 43.1% people favour BJP, 29.6% lean towards SP,” July 17, 2021, https://www.timesnownews.com/india/article/times-now-cvoter-up-poll-tracker-43-1-people-favour-bjp-29-6-lean-towards-sp/786209; Republic, “Republic-CVoter Exit Poll Projection: NDA Will Cross Halfway Mark, Modi Set To Form The Government Again, Congress Likely To Fall Short Of 100 Mark,” May 19, 2019, https://www.republicworld.com/election-news/indian-general-elections/republic-cvoter-exit-poll-projection-nda-will-cross-halfway-mark-modi-set-to-form-the-government-again-congress-likely-to-fall-short-of-100-mark.html; and Nikhar Gaikwad and Gareth Nellis, “Do Politicians Discriminate Against Internal Migrants? Evidence from Nationwide Field Experiments in India,” American Journal of Political Science 65, no. 4 (2021): 790-806. CVoter also regularly provides electoral predictions in India’s notoriously volatile election landscape. While there have been accusations of bias on electoral predictions, a recent analysis found its polling is reasonably comparable in predicting winners and margins of victory (“Indian pollsters are doing fine. Here is how forecasts work,” March 27, 2022.)

- 4Note: With an overall sample size of 7,052, a conservative 95% confidence interval on categorical responses is 1.2 percentage points for the whole survey. Because this article uses subgroup analysis, the subgroup-specific 95% confidence intervals are displayed in the figures.

- 5Note: All results use post-stratification weights to make them comparable to the 2011 Indian Census. The Census allows us to adjust for population counts by age, gender, identity group (religion, scheduled caste, and scheduled tribe), and urban/rural status across states.

- 6Note: Sumathi Bala, “Political setbacks dent Modi’s strongman image as India heads for crucial state polls,” CNBC, January 19, 2022.

- 7Note: Our survey included experimental vignettes, but if a question was asked after the experimental vignettes, we have only including findings present in control condition as well as treatment groups.

- 8Note: “BJP Managed to Convince People We Are a Muslim Party: Sonia Gandhi,” The Indian Express, March 10, 2018.

- 9Note: N. P. Ashley, “The AAP is not opposing the BJP precisely in the way liberals and radicals want,” The Indian Express, February 16, 2020.

- 10Note: Gerry Shih, “India Scrambles to Contain Fallout over Insulting Comments about Islam,” Washington Post, June 7, 2022.

- 11Note: U.S. Department of State, 2021 Report on International Religious Freedom, June 2, 2022, https://www.state.gov/reports/2021-report-on-international-religious-freedom/.

- 12Note: This is slightly higher than a 2013 survey that found 82 percent of Indian respondents agreeing somewhat or strongly with this statement, making India the second most nationalist country by this measure (after Japan). “International Social Survey Programme: National Identity III – ISSP 2013,” https://search.gesis.org/research_data/ZA5950.

- 13Note: General Social Survey, “Agree America is a Better Country,” https://gssdataexplorer.norc.org/variables/4837/vshow.

- 14Note: “Army Chief MM Narvane talks tough on China: ‘We will win in case of war’,” ZeeNews, January 12, 2022, https://zeenews.india.com/india/army-chief-mm-narvane-talks-tough-on-china-we-will-win-in-case-of-war-2427377.html.

- 15Note: Sushant Singh, “Why China is Winning against India,” Foreign Policy, January 1, 2021; Detesfra_ and Sim Tack, “China-India Border Crisis Has Quietly Resulted In Victory For Beijing,” The Drive, May 23, 2022.

- 16Note: Vasabjit Banerjee and Timothy S. Rich. “Which side would the US public choose in an India-China conflict?,” The Interpreter, July 30, 2020, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/which-side-would-us-public-choose-india-china-conflict.

- 17Note: Asian News International (ANI), “India Has To Fight Its Own Wars, US Deployments According To Their Perspective: IAF Chief,” BW Businessworld, October 5, 2020, https://www.businessworld.in/article/India-has-to-fight-its-own-wars-US-deployments-according-to-their-perspective-IAF-Chief/05-10-2020-328212/; “Explained Ideas: Why India can’t depend on the US and EU to counter China,” The Indian Express, June 29, 2020, https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/india-china-border-dispute-the-ue-eu-6477314/; Kartik Bommakanti, “American military support to India is not automatic in China-India war. Delhi must know it,” The Print, July 22, 2020, https://theprint.in/opinion/american-military-support-to-india-is-not-automatic-in-china-india-war-delhi-must-know-it/466196/.

- 18Note: Hans M. Kristensen and Matt Korda, “Indian nuclear forces, 2020,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 76, no. 4 (2020): 217-225; Kristensen and Korda, “Pakistani nuclear weapons, 2021,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 77, no. 5 (2021): 265-278; Kristensen and Korda, “Chinese nuclear weapons, 2021,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 77, no. 6 (2021): 318-336.

- 19Note: Office of the Secretary of Defense, Military and Security Developments involving the People’s Republic of China (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2021), 90.

- 20Note: Vipin Narang & Paul Staniland, “Democratic Accountability and Foreign Security Policy: Theory and Evidence from India,” Security Studies, 27 (3), 2018, pp. 410-447.

- 21Note: Also see Morning Consult, “Global Leader Approval Ratings,” https://morningconsult.com/global-leader-approval/ (updated June 9, 2022).

- 22Note: S. Jaishankar, The India Way: Strategies for an Uncertain World (Noida: HarperCollins Publishers India, 2020).

- 23Note: Anjali Ghodvaidya, “Mideast Oil Suppliers Condemn Insults on Islam by Modi’s Party,” Bloomberg News, June 6, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-06-06/mideast-oil-suppliers-condemn-insults-on-islam-by-modi-s-party.

- 24Note: Christopher Clary, “Deterrence Stability and the Conventional Balance of Forces in South Asia,” in Deterrence Stability and Escalation Control in South Asia, eds. Michael Krepon and Julia Thompson (Washington, DC: The Henry L. Stimson Center, 2013); Frank O’Donnell and Alex Bollfrass, The Strategic Postures of China and India: A Visual Guide (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Kennedy School Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, March 2020).

- 25Note: Daniel Kliman, Iskander Rehman, Kristine Lee and Joshua Fitt, “Imbalance of Power: India’s Military Choices in an Era of Strategic Competition with China,” Center for New American Security, October 2019, https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/imbalance-of-power.

- 26Note: “India asked Washington not to bring up China’s border transgressions: Former US ambassador,” Scroll.in, March 2, 2022, https://scroll.in/latest/1018580/india-asked-washington-not-to-mention-chinas-border-transgressions-former-us-ambassador-to-india.

- 27Note: Benjamin A. Valentino and Scott D. Sagan, “Atomic Attraction,” The Indian Express, June 3, 2016.

- 28Note: He specifically stated that India’s nuclear weapons were not for use only in the Indian festival of Divali, commonly celebrated with fireworks displays. “Have we kept our nuclear bomb for Diwali, asks Narendra Modi,” The Hindu, April 21, 2019.