Recommendation:

Increase the universal acceptance of international justice institutions, in particular the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the International Criminal Court (ICC). Moreover, increase their enforcement powers, preserve their independence, and enhance their resilience against political pressures.

Global Challenge Update:

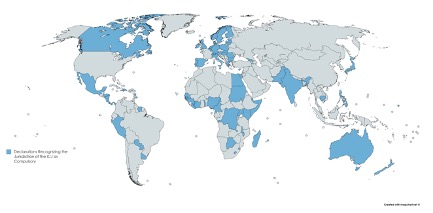

International courts and dispute settlement institutions are an integral part of rules-based global governance. However, in today’s environment characterized in many places by an “anti-multilateralist turn,” 1Larik Joris, William Durch and Richard Ponzio. “Reinvigorating Global Governance Through ‘Just Security’”. The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs 44(1) (2020): 18–22. they are subject to severe political pressures and criticisms, while they often lack the universal reach, enforcement mechanisms, and resilience to effectively carry out their mandates. The fate of the Appellate Body of the World Trade Organization (WTO), which was shut down in December 2019 by persistent U.S. refusal to agree to the appointment of new members, is a cautionary tale for other international courts and tribunals. Harsh criticism of the ICC by the United States and some non-Western countries has not led to a mass exodus from the Court, although the Philippines and Burundi have formally withdrawn from it. Furthermore, Asian countries remain underrepresented at the ICC as China, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Nepal, Vietnam, and Myanmar, among others, are not parties to the Rome Statute. Moreover, only 74 of the world’s nations accept the ICJ’s compulsory jurisdiction in general terms, among which the United Kingdom is the only permanent UN Security Council member (see map).

Figure 1: Map highlighting countries that accept the ICJ’s compulsory jurisdiction under the “Optional Clause”

At the same time, the continued demand for international courts is evident from high-profile cases such as the Gambia v. Myanmar case concerning the latter’s obligations under the Genocide Convention and the thirteen active ICC investigations (five of which were referred to the ICC by the countries in questions and two by the UN Security Council). 2International Criminal Court. “Situations under investigation.” Accessed March 3, 2020. https://www.icc-cpi.int/pages/situation.aspx.

Innovation Proposal:

International judicial institutions need to increase both their reach and resilience. Regarding their reach, to effectively carry out their mandates, international justice institutions require acceptance throughout the global community and the ability to avail themselves of mechanisms to enforce their decisions.

For the International Court of Justice, this requires, firstly, expanding the acceptance of the court’s compulsory jurisdiction through so-called “optional clause” declarations under Article 36(2) of the ICJ Statute. An in-depth study on the reasons why countries have not made use of the “optional clause” yet, followed by a global campaign to address these reasons and increase the number of countries accepting the ICJ’s jurisdiction, are needed to ensure that international disputes are addressed in courts of law, rather than direct, possibly violent, confrontation. 3Commission on Global Security, Justice & Governance. “Confronting the Crisis of Global Governance.” The Hague Institute for Global Justice and the Stimson Center, June 2015, 90. In addition, a more active use of the ICJ’s advisory opinions—non-binding but authoritative—can extend its reach in addressing legal questions on pressing global challenges. The UN General Assembly and UN specialized agencies, where no vetoes apply, should make greater use of their powers to request such opinions. To make sure the ICJ’s judgments are enforced, it has to rely on the UN Security Council, 4Art. 94(2) of the UN Charter. where the use of the veto powers of the permanent five members can easily derail such efforts. Therefore, the ongoing campaigns for codes of conduct on restraining the use of the veto—chiefly those of the Accountability, Coherence and Transparency (ACT) group and the French-Mexican initiative—should include a commitment not to obstruct resolutions that enforce ICJ judgments.

Similarly, the International Criminal Court’s reach should be expanded by an in-depth study to better understand (non-P5) countries’ hesitations in joining the Rome Statute. A campaign to boost ICC membership, with an emphasis on Asia as the most underrepresented region, could strengthen the body’s credentials as a universal institution. Regarding enforcement, the ICC—though not formally part of the UN system—should establish enhanced working methods with the UN Security Council, including a protocol or code to guide Council decisions to support ICC investigations and prosecutions, including sanctions (such as asset freezing), to enforce ICC arrest warrants.

The vulnerability of international courts and tribunals to being rendered nonoperational should be urgently assessed. In addition to contingency planning, which can draw on the substitute solutions being currently developed for the WTO, the ICJ and ICC should be “stress-tested” and reformed to strengthen their resilience, including as regards to the need for appropriate funding, premises, and freedom to operate without political interference.

Strategy for Reform on the Road to 2020 (UN75):

These proposals can be achieved without having to pass large political and legal thresholds, such as UN Charter amendment. Many can be achieved without the consent of the P5. The in-depth studies necessary to underpin the ensuing campaigns could be launched in the wake of the September 2020 Leaders Summit in New York and the General Assembly’s 75th Session, while existing government-led initiatives, such as the “Alliance for Multilateralism” and the “Accountability, Coherence and Transparency (ACT)” group, can become champions for a drive to extend the reach and resilience of international justice institutions. Deep opposition from certain powerful countries notwithstanding, as the initiative led by Canada and the EU for substitute solutions in trade dispute settlement shows, coalitions of interested parties can achieve workarounds, while remaining open to others. Increasing the number of states that accept the ICJ’s and the ICC’s jurisdiction is essential to crafting a coalition to boost international justice institutions as an integral part of the rules-based multilateral order. This will lay the groundwork for more ambitious goals, such as ensuring that a majority of the world’s nations issue “optional clause” declarations under the ICJ or adopt a much-needed document on ICC-UNSC cooperation.

Notes

- 1Larik Joris, William Durch and Richard Ponzio. “Reinvigorating Global Governance Through ‘Just Security’”. The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs 44(1) (2020): 18–22.

- 2International Criminal Court. “Situations under investigation.” Accessed March 3, 2020. https://www.icc-cpi.int/pages/situation.aspx.

- 3Commission on Global Security, Justice & Governance. “Confronting the Crisis of Global Governance.” The Hague Institute for Global Justice and the Stimson Center, June 2015, 90.

- 4Art. 94(2) of the UN Charter.