By Rachel Blomquist & Richard Cincotta:

According to political demographers, who study the relationship between population dynamics and politics, two characteristics when observed together provide a rather good indication that a state is about to shed its authoritarian regime, rise to a high level of democracy, and stay there. Myanmar has both.

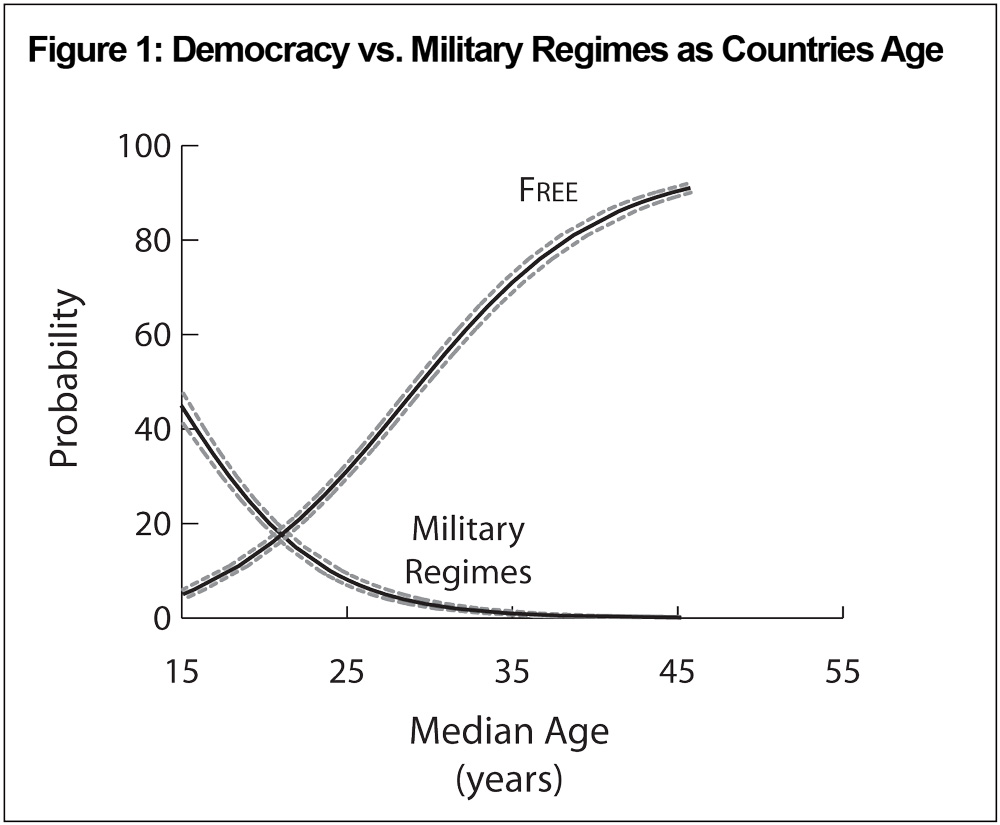

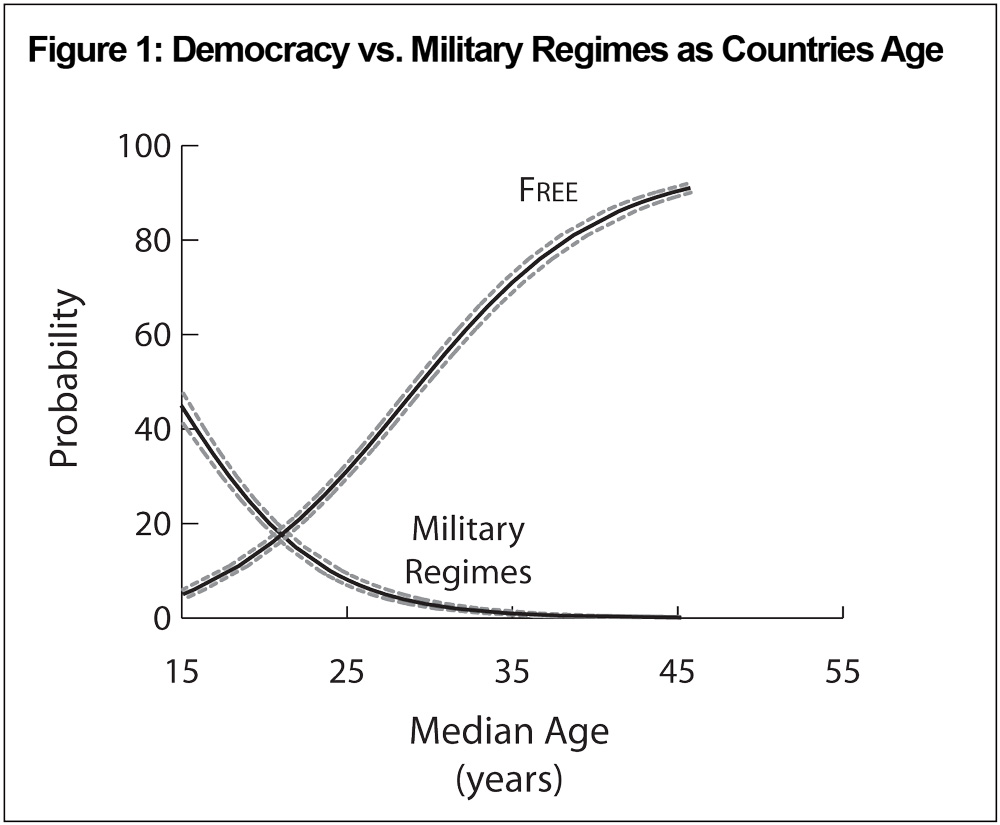

The first is demographic: the “right” age structure. A median age of 29 years marks the point when the historical probability of a country being a democracy, measured by Freedom House’s annual study of political rights and civil liberties, passes the 50-percent mark. According to the United Nations Population Division, Myanmar’s median age at mid-year 2015 was at 27.9 years and it is projected to pass the 50-percent mark in 2019.

The second is political: a pragmatic (rather than ideological) military-controlled government. This type of regime, although always repressive and sometimes ruthless, has proven exceedingly vulnerable to democratization as a country’s age structure matures. Only a handful of military regimes have survived past a median age of 30 years (Figure 1).

So why, despite an impressive succession of social reforms and political reversals, including the recent victory of the National League for Democracy led by Aung San Suu Kyi and the first elected civilian president, U Htin Kyaw, should analysts remain somewhat skeptical of Myanmar’s ability to make the leap to liberal democracy? The answer can be found in Myanmar’s dismal record of managing inter-ethnic politics, particularly the systematically disenfranchised Muslim Rohingya minority.

Population Problems?

During the pre-census mapping phase of the 2014 census, Myanmar’s Department of Population estimated about 1 million people who self-identified as Rohingya in Rakhine State, 31 percent of the state’s population. Yet the census classified them as “not enumerated.” Most reside primarily in the western portion of Rakhine State and are stateless – officially considered a foreign population by Myanmar’s central government.

Whereas relatively small but significant Rohingya insurgent activities, run by the Rohingya Solidarity Organization (RSO), have operated off-and-on near the Bangladesh border since independence, there has been little evidence of recent RSO activity. Generally, Rohingya communities have been the targets of discrimination and political violence at the hands of neighboring Rakhine Buddhists, another of Myanmar’s minorities. In recent years,thousands of Rohingya have risked their lives (and many have lost them) illegally crossing densely forested borders or paying the crews of fishing vessels who drop them along the coasts of neighboring states.

Inter-ethnic demographic differences play a prominent role in the conflict. Buddhist nationalists – represented by organizations such as MaBaTha and the 969 Movement – assert that persistently high rates of population growth among the Rohingya have reduced Rakhine communities to a minority in the western districts of Rakhine State, territory once ruled by Arakan kings and populated by the ancestors of today’s Rakhine Buddhists. The Rohingya have thus become the target of local regulations obstructing family formation, and more recently, the focus of central government legislation seeking to regulate childbearing.

In our research, we have explored two key questions that concern the origins and dynamics of the Rohingya conflict. The first question is demographic: Are Rakhine Buddhists’ perceptions accurate – that Rohingya fertility is higher, and their growth rate is faster than other local populations? Our second question is political: Can the central government in Naypyidaw help reduce these ethno-demographic differences in the long run?

A Youthful Minority

As a general rule, where information about ethnic demographics has critical political implications, data is likely to be scarce. So it is in Myanmar.

Because those who self-identified as Rohingya were not enumerated in Myanmar’s 2014 census, our estimates rely on an analysis using rates obtained from local surveys of Maungdaw Township in northern Rakhine State. Nearly 90 percent of the township’s 512,000 residents identified as Rohingya in surveys conducted by the United Nations (or “Bengalis” in Myanmar’s documentation), a significant proportion of the state’s Rohingya. Using estimates of crude rates provided by to the United Nations by Myanmar’s government, we employed standard demographic tables and statistical techniques to reconstruct an age structure and estimate fertility and growth.

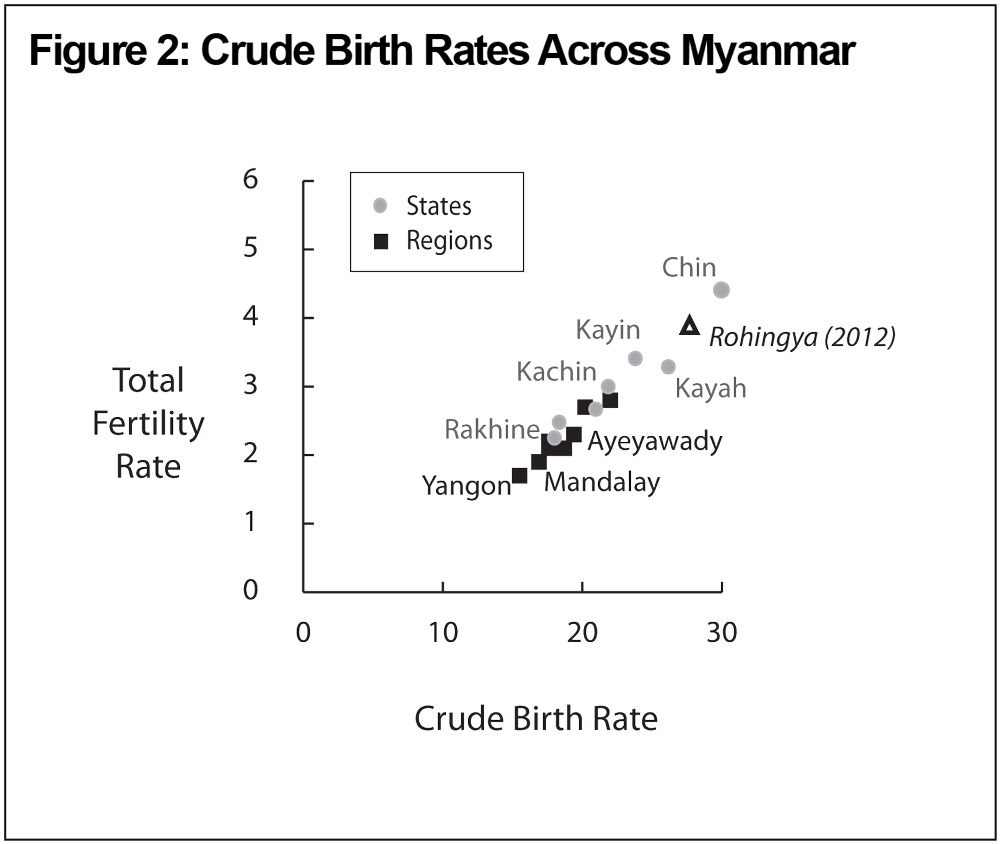

While our conclusions are necessarily tentative, our estimate of the Rohingya sample’s total fertility rate (number of children born per woman over her lifetime) for 2012 is about 3.8, and we estimate its population growth was at 1.5 percent per year. While neither Rohingya fertility nor growth rates were as high as corresponding rates in Myanmar’s Chin State (adjacent to Rakhine State and also bordering Bangladesh), they were considerably higher than published current estimates of Rakhine Buddhist total fertility rate, at 2.2 children per woman (Figure 2).

The Dilemma

These results seem to confirm perceptions of the Rohingya growing more quickly than Rakhine Buddhists, but what about the second question: what can – or should – the government do about it, if anything?

To structure our analysis, we rely on a theory that Christian Leuprecht refers to as the “demographic security dilemma.” While reviewing contemporary studies of states with escalating inter-ethnic tensions, he frequently noted a wide ethnic fertility gap, separating the majority from the minority. Typically, the marginalized minority experienced a substantially higher level of fertility than the majority – often as much as two children per woman, and sometimes more. Leuprecht explained these gaps as products of a policy dilemma.

The dilemma, Leuprecht argues, arises when the state reacts to minority population growth by denying minority members proper access to services, constraining their economic mobility, and suppressing their political rights. These are conditions that have been experienced by the Rohingya. For many, conditions are far worse. According to International Crisis Group,upwards of 137,000 people in Rakhine State, mostly Rohingya, remain in displacement camps following violence in 2012.

Leuprecht noted that such policies are self-defeating. When further marginalized, high-fertility minorities – typically already less educated and poorer, more religious, usually rural, and with less access to modern contraception than their urban counterparts – are inclined to retain, or even revert to, traditional patterns of marriage and childbearing, and practices that constrain women’s activities outside the home and sustain high fertility.

Paradoxically, marginalization can ultimately slow or stifle minority fertility decline, widen the ethnic fertility gap, promote minority population growth, and yield even larger proportions of minority young adults. Past and present examples of this include the treatment of Palestinians in Israel, Indios groups in Guatemala and the Andean states, Pattani Muslims in Thailand, Muslims in northern India, African Americans in the United States, Tamils in Sri Lanka, and the Sinai Bedouin in Egypt. While economically weakening minority communities in the short run, such policies threaten to erode the demographic position of the majority – and worse.

In the case of Myanmar, the central government’s lack of response to the discrimination and violence suffered by the Rohingya is fashioning an inviting political environment for Islamic extremism. Whereas recent government-reported RSO activity has been difficult to substantiate, that could change if the current situation is left to brew for too long. Without some attempt to resolve the dilemma, Naypyidaw runs the risk of creating its own worst nightmare – the rise of another ethnic insurgency and the more diffuse threat of terrorism.

Is a Turnabout Possible?

Theoretically, the surest and most logical pathway out of the minority demographic security dilemma is (as Leuprecht notes) a full 180-degree policy reversal. That’s not an easy political pill to swallow anywhere. Moreover, too rapid a turnabout would alarm Rakhine Buddhist communities.

On the other hand, it is unlikely that the international community, with the possible exception of China, which has had considerable political, economic, and security influence over Myanmar’s military junta, will continue to tolerate reproductive coercion and forced migration as the centerpieces of Naypyidaw’s Rohingya policy. And given the past five years of turbulent relations between Naypyidaw and Beijing – including China’s sunken investment in the suspended Myitsone Dam and the Kokong conflict near the border in Myanmar’s northeast – neither Myanmar’s military establishment nor the new National League for Democracy seems eager to wedge themselves into a geopolitical corner where China is their one and only friend.

What would such a policy reversal mean? Rather than turning a blind eye to disruptive inter-ethnic violence, the central government would need to actively protect Rohingya communities.

Instead of keeping the Rohingya at the margins of society, the state would double investments in Rohingya health care and secular education, and ensure that Rohingya girls and women have the opportunity to complete high school education and beyond.

Rather than attempting to enforce restrictions on reproduction, the Naypyidaw government would secure women’s access to state-run secular family courts (as opposed to informal village or religious adjudication) while providing quality maternal and child health care, and family planning.

Impossible? In today’s Myanmar, very nearly. Such a turnabout would require the expenditure of enormous political capital, at a level held by only top officials in the government. Moreover, the reversal would precipitate an early showdown with popular Buddhist nationalists – something that Aung San Suu Kyi would rather put off to a later date. She may not have that luxury. The path to democracy seems to cut directly through the Rohingya issue.

It is no easy task to meld a unified modern state from the diverse cultural and linguistic mixture of peoples who once settled and established kingdoms on the fertile flood plains of the Irrawaddy and hills surrounding the Salween and Mekong. At independence, the new government inherited a long list of promises of autonomy and territorial concessions made by the British colonial government to many of the country’s minorities. Although the military has negotiated a halt to 8 of the country’s 15 active ethnic conflicts, the government is still far from either quelling ethnic separatism or eliminating inter-ethnic violence. Meanwhile, the Rohingya are still struggling for their most basic right – to be considered citizens in the land of their birth. As the National League for Democracy works to consolidate its power in the coming years, it will be telling to see whether the Rohingya are included in Suu Kyi’s vision of a free Myanmar.

Rachel Blomquist is a Master’s candidate at Georgetown University’s Asian Studies Program in the School of Foreign Service. This research is a product of her internship at the Stimson Center and her Master’s thesis.Richard Cincotta is a Wilson Center global fellow and director of the Global Political Demography Program at the Stimson Center

Sources: Department of Population (Myanmar), Freedom House, Human Rights Watch, International Crisis Group, Studies in Population, UNFPA, United Nations.

This piece originally ran in New Security Beat, April 12, 2016

Myanmar’s Democratic Deficit: Demography and the Rohingya Dilemma

By Richard Cincotta

In

By Rachel Blomquist & Richard Cincotta:

According to political demographers, who study the relationship between population dynamics and politics, two characteristics when observed together provide a rather good indication that a state is about to shed its authoritarian regime, rise to a high level of democracy, and stay there. Myanmar has both.

The first is demographic: the “right” age structure. A median age of 29 years marks the point when the historical probability of a country being a democracy, measured by Freedom House’s annual study of political rights and civil liberties, passes the 50-percent mark. According to the United Nations Population Division, Myanmar’s median age at mid-year 2015 was at 27.9 years and it is projected to pass the 50-percent mark in 2019.

The second is political: a pragmatic (rather than ideological) military-controlled government. This type of regime, although always repressive and sometimes ruthless, has proven exceedingly vulnerable to democratization as a country’s age structure matures. Only a handful of military regimes have survived past a median age of 30 years (Figure 1).

So why, despite an impressive succession of social reforms and political reversals, including the recent victory of the National League for Democracy led by Aung San Suu Kyi and the first elected civilian president, U Htin Kyaw, should analysts remain somewhat skeptical of Myanmar’s ability to make the leap to liberal democracy? The answer can be found in Myanmar’s dismal record of managing inter-ethnic politics, particularly the systematically disenfranchised Muslim Rohingya minority.

Population Problems?

During the pre-census mapping phase of the 2014 census, Myanmar’s Department of Population estimated about 1 million people who self-identified as Rohingya in Rakhine State, 31 percent of the state’s population. Yet the census classified them as “not enumerated.” Most reside primarily in the western portion of Rakhine State and are stateless – officially considered a foreign population by Myanmar’s central government.

Whereas relatively small but significant Rohingya insurgent activities, run by the Rohingya Solidarity Organization (RSO), have operated off-and-on near the Bangladesh border since independence, there has been little evidence of recent RSO activity. Generally, Rohingya communities have been the targets of discrimination and political violence at the hands of neighboring Rakhine Buddhists, another of Myanmar’s minorities. In recent years,thousands of Rohingya have risked their lives (and many have lost them) illegally crossing densely forested borders or paying the crews of fishing vessels who drop them along the coasts of neighboring states.

Inter-ethnic demographic differences play a prominent role in the conflict. Buddhist nationalists – represented by organizations such as MaBaTha and the 969 Movement – assert that persistently high rates of population growth among the Rohingya have reduced Rakhine communities to a minority in the western districts of Rakhine State, territory once ruled by Arakan kings and populated by the ancestors of today’s Rakhine Buddhists. The Rohingya have thus become the target of local regulations obstructing family formation, and more recently, the focus of central government legislation seeking to regulate childbearing.

In our research, we have explored two key questions that concern the origins and dynamics of the Rohingya conflict. The first question is demographic: Are Rakhine Buddhists’ perceptions accurate – that Rohingya fertility is higher, and their growth rate is faster than other local populations? Our second question is political: Can the central government in Naypyidaw help reduce these ethno-demographic differences in the long run?

A Youthful Minority

As a general rule, where information about ethnic demographics has critical political implications, data is likely to be scarce. So it is in Myanmar.

Because those who self-identified as Rohingya were not enumerated in Myanmar’s 2014 census, our estimates rely on an analysis using rates obtained from local surveys of Maungdaw Township in northern Rakhine State. Nearly 90 percent of the township’s 512,000 residents identified as Rohingya in surveys conducted by the United Nations (or “Bengalis” in Myanmar’s documentation), a significant proportion of the state’s Rohingya. Using estimates of crude rates provided by to the United Nations by Myanmar’s government, we employed standard demographic tables and statistical techniques to reconstruct an age structure and estimate fertility and growth.

While our conclusions are necessarily tentative, our estimate of the Rohingya sample’s total fertility rate (number of children born per woman over her lifetime) for 2012 is about 3.8, and we estimate its population growth was at 1.5 percent per year. While neither Rohingya fertility nor growth rates were as high as corresponding rates in Myanmar’s Chin State (adjacent to Rakhine State and also bordering Bangladesh), they were considerably higher than published current estimates of Rakhine Buddhist total fertility rate, at 2.2 children per woman (Figure 2).

The Dilemma

These results seem to confirm perceptions of the Rohingya growing more quickly than Rakhine Buddhists, but what about the second question: what can – or should – the government do about it, if anything?

To structure our analysis, we rely on a theory that Christian Leuprecht refers to as the “demographic security dilemma.” While reviewing contemporary studies of states with escalating inter-ethnic tensions, he frequently noted a wide ethnic fertility gap, separating the majority from the minority. Typically, the marginalized minority experienced a substantially higher level of fertility than the majority – often as much as two children per woman, and sometimes more. Leuprecht explained these gaps as products of a policy dilemma.

The dilemma, Leuprecht argues, arises when the state reacts to minority population growth by denying minority members proper access to services, constraining their economic mobility, and suppressing their political rights. These are conditions that have been experienced by the Rohingya. For many, conditions are far worse. According to International Crisis Group,upwards of 137,000 people in Rakhine State, mostly Rohingya, remain in displacement camps following violence in 2012.

Leuprecht noted that such policies are self-defeating. When further marginalized, high-fertility minorities – typically already less educated and poorer, more religious, usually rural, and with less access to modern contraception than their urban counterparts – are inclined to retain, or even revert to, traditional patterns of marriage and childbearing, and practices that constrain women’s activities outside the home and sustain high fertility.

Paradoxically, marginalization can ultimately slow or stifle minority fertility decline, widen the ethnic fertility gap, promote minority population growth, and yield even larger proportions of minority young adults. Past and present examples of this include the treatment of Palestinians in Israel, Indios groups in Guatemala and the Andean states, Pattani Muslims in Thailand, Muslims in northern India, African Americans in the United States, Tamils in Sri Lanka, and the Sinai Bedouin in Egypt. While economically weakening minority communities in the short run, such policies threaten to erode the demographic position of the majority – and worse.

In the case of Myanmar, the central government’s lack of response to the discrimination and violence suffered by the Rohingya is fashioning an inviting political environment for Islamic extremism. Whereas recent government-reported RSO activity has been difficult to substantiate, that could change if the current situation is left to brew for too long. Without some attempt to resolve the dilemma, Naypyidaw runs the risk of creating its own worst nightmare – the rise of another ethnic insurgency and the more diffuse threat of terrorism.

Is a Turnabout Possible?

Theoretically, the surest and most logical pathway out of the minority demographic security dilemma is (as Leuprecht notes) a full 180-degree policy reversal. That’s not an easy political pill to swallow anywhere. Moreover, too rapid a turnabout would alarm Rakhine Buddhist communities.

On the other hand, it is unlikely that the international community, with the possible exception of China, which has had considerable political, economic, and security influence over Myanmar’s military junta, will continue to tolerate reproductive coercion and forced migration as the centerpieces of Naypyidaw’s Rohingya policy. And given the past five years of turbulent relations between Naypyidaw and Beijing – including China’s sunken investment in the suspended Myitsone Dam and the Kokong conflict near the border in Myanmar’s northeast – neither Myanmar’s military establishment nor the new National League for Democracy seems eager to wedge themselves into a geopolitical corner where China is their one and only friend.

What would such a policy reversal mean? Rather than turning a blind eye to disruptive inter-ethnic violence, the central government would need to actively protect Rohingya communities.

Instead of keeping the Rohingya at the margins of society, the state would double investments in Rohingya health care and secular education, and ensure that Rohingya girls and women have the opportunity to complete high school education and beyond.

Rather than attempting to enforce restrictions on reproduction, the Naypyidaw government would secure women’s access to state-run secular family courts (as opposed to informal village or religious adjudication) while providing quality maternal and child health care, and family planning.

Impossible? In today’s Myanmar, very nearly. Such a turnabout would require the expenditure of enormous political capital, at a level held by only top officials in the government. Moreover, the reversal would precipitate an early showdown with popular Buddhist nationalists – something that Aung San Suu Kyi would rather put off to a later date. She may not have that luxury. The path to democracy seems to cut directly through the Rohingya issue.

It is no easy task to meld a unified modern state from the diverse cultural and linguistic mixture of peoples who once settled and established kingdoms on the fertile flood plains of the Irrawaddy and hills surrounding the Salween and Mekong. At independence, the new government inherited a long list of promises of autonomy and territorial concessions made by the British colonial government to many of the country’s minorities. Although the military has negotiated a halt to 8 of the country’s 15 active ethnic conflicts, the government is still far from either quelling ethnic separatism or eliminating inter-ethnic violence. Meanwhile, the Rohingya are still struggling for their most basic right – to be considered citizens in the land of their birth. As the National League for Democracy works to consolidate its power in the coming years, it will be telling to see whether the Rohingya are included in Suu Kyi’s vision of a free Myanmar.

Rachel Blomquist is a Master’s candidate at Georgetown University’s Asian Studies Program in the School of Foreign Service. This research is a product of her internship at the Stimson Center and her Master’s thesis.Richard Cincotta is a Wilson Center global fellow and director of the Global Political Demography Program at the Stimson Center

Sources: Department of Population (Myanmar), Freedom House, Human Rights Watch, International Crisis Group, Studies in Population, UNFPA, United Nations.

This piece originally ran in New Security Beat, April 12, 2016

Photo credit: United to End Genocide via Flickr